Welcome to Juan Soto’s MLB

No one owns the batter's box like the 22-year-old phenom -- who soon might just shuffle his way into history.

He licks his lips and wags his hips and stares with contempt at the man standing 60 feet away from him, and anyone who sees this routine might think Juan Soto is, at best, a preening jerk. And, to be fair, this is not an entirely inaccurate read on the situation, not as Soto peacocks about the 4-foot-wide-by-6-foot-deep batter's box, the most valuable 24 square feet of real estate on a baseball field.

It is, unequivocally, his space, so much so that at one point earlier in his career, when a 19-year-old Soto was just beginning his assault on major league pitching, his in-game antics included a crotch grab. He has since excised this from his sequence because, it turns out, for the 23 hours, 45 minutes or so a day he spends outside of the box, Soto is actually an unfailingly polite, conscientious, thoughtful person, and he worried about the example he was setting. "There's kids looking," he says.

For those other 15 minutes, everything but the self-cup-check remains, because why wouldn't it? Over the past three years, as Soto has rewritten records, won a World Series with the Washington Nationals and placed himself on one of the quickest Hall of Fame tracks in the past century, he did it his way, the way others told him couldn't work. Soto is flouting the rules in a sport in which the box belongs to the game and is only rented out to its inhabitants, who must abide by a strict code.

Outside of that space, Juan Soto is not a rule breaker. He is 22 but doesn't party. He lives across the street from Nationals Park. He refers to elders as mister and missus. It's as if stepping into that rectangle activates an alter ego.

"When he's in that box, he feels like his best version of himself," says Trea Turner, the Nationals shortstop and a close friend. "And that's where he can be himself and just have a lot of fun. And I think he enjoys it probably more than anything in life, other than his family and friends."

In there, Soto is all id, unencumbered instinct. He digs in softly with his left foot and balances on his pigeon-toed right, his weight split 50-50, simultaneously graceful and powerful. He steadies his midsection and waggles his hands. Then begins the dance, an arrhythmic improvisation, hip-heavy and front-to-back.

Pitchers desperately want to throw Soto off, to do anything to disrupt the timing that allows him to square up baseballs with alarming regularity. His swing is too perfect and his eye too discerning for them to give in to his psychological stylings. And yet, as Soto eyeballs pitchers, well aware that most are trying to avoid his glare, they find themselves in a Catch-22 of his making. Lock eyes with him, allow him to see a whiff of fear, and he wins. Avoid his gaze and he wins, too. "When they see me, they're like, 'You think you're better than me?'" Soto says. "And I'm like, 'Yes, I'm better than you.'"

This is just the beginning of Soto's career, and he's still got so much to figure out: who he is and what he wants to be and how to handle fame and whether becoming American sports' first $500 million player is within reach or even something he desires. Inside that box, though? He's already got everything he could ever need.

Even when the pitcher he's dueling happens to be the best in the game.

THE FIRST TWO parts of Juan Soto's most triumphant three-act play happened in relatively expedient fashion. It was Oct. 22, 2019, Game 1 of the World Series, and the Nationals were facing Gerrit Cole, who had won his past 16 starts on the back of his hard-harder-hardest-hardestest four-pitch array. For all the impediments Washington's lineup presented, none had a better chance to derail the Cole train than Soto, the third-youngest cleanup hitter ever in a championship series.

In the first inning, Cole attacked Soto with three fastballs. Soto swung through the first at 97 mph, stared at a strike at 98 and waved through the final one at 99. The next time up, Cole missed with a fastball before leaving a slider up in the strike zone. Soto lofted it to left-center field, and it climbed like balls off the bats of left-handed hitters to the opposite field simply don't, settling finally 417 feet away, onto the train tracks at Minute Maid Park -- a majestic home run.

The rubber at-bat came in the fifth inning, with two runners on and the Nationals leading 3-2. Soto brought his A-plus troll game to the plate. As he stepped in, he stuck out his tongue. He shimmied. He was looking for a fastball -- he wanted to swing. Cole greeted him with a biting slider, down and in, prompting Soto to scamper out of the way.

It was the sort of pitch that might discomfit a lesser hitter. But for Soto, it was no different from the objects with which his father, Juan Sr., challenged him when he was growing up in Santo Domingo, the capital city of the Dominican Republic. Sometimes it was crumpled-up paper. Other times it was rocks. Or bottle caps. Whenever Soto gripped a bat, his father fed him something to whack. Inside, outside, up, down or, like Cole's slider, low and tight.

Soto hit and threw with both hands until his father saw a natural gift from the left side. At 15, Soto caught the eye of a local trainer, Cristian "Niche" Batista, who regularly fetched six- and seven-figure bonuses for teenage players he coached. Soto spent weekdays living at Niche's academy before returning home on weekends to continue his schooling, which his father, a salesman, and his mother, an accountant, insisted upon when they agreed to let him pursue a professional career.

Nationals scout Modesto Ulloa first saw Soto as a pitcher, where his arm didn't distinguish him. After catching a glimpse of Soto swinging, Ulloa called Johnny DiPuglia, the Nationals' director of Latin American operations, and asked him to give Soto a look on his next visit to the D.R. DiPuglia liked Soto's swing. He loved his makeup, the baseball term for the amalgamation of intelligence, attitude, work ethic and personality. When DiPuglia and Nationals general manager Mike Rizzo met Soto, they said his humility sold them as much as his swing.

In late October, almost five years to the day before his epic showdown with Cole, Soto flew to Florida for a Dominican Prospect League tournament with dozens of other Latin American teenagers who planned to sign the first day they could, July 2, 2015. Among his teammates: Fernando Tatis Jr., whom the Chicago White Sox would get for $825,000. The White Sox were pursuing Soto as well, willing to give him a $1.4 million signing bonus, and he believed he was likely to agree with them until Oct. 22, the final day of the tournament. DiPuglia and Deric Ladnier, a high-ranking Nationals scout, asked Niche for a private hitting session with Soto in a batting cage at Fort Lauderdale Stadium.

DiPuglia and Ladnier flipped balls to Soto to see how the barrel of his bat moved through different parts of the strike zone. Satisfied, they told Niche the Nationals were willing to pay $1.5 million. Niche agreed to the number and they shook hands. Soon thereafter, De Jon Watson, a top executive with Arizona who was interested in Soto, walked by the cage and asked what was going on. "It's a done deal," DiPuglia said.

His confidence would be tested. Three hours after Soto pledged to be a National, the Kansas City Royals called to offer $1.7 million. The next day, the San Diego Padres said they were willing to pay $2 million. Soto could have taken the money, become a White Sox or a Diamondback or a Royal or a Padre. But DiPuglia's read of Soto's makeup was spot-on. No amount of money would make him go back on his word.

The shuffle is the apex of Soto's mind games -- mostly performative, though at least the performance is quite magnificent. Mary Beth Koeth for ESPN

AFTER AVOIDING COLE'S yanked slider, Soto gathered himself and stepped back into the box. He leered at the pitcher and sniffed. He thrust his front hip forward. He again prepared for a fastball and instead stared at an 86 mph curveball that spun high and outside. And then he shuffled.

The Soto Shuffle isn't a shuffle in the true sense of the word. Were it to be renamed, it would be the Soto Slide, or maybe the Soto Shimmy, if loose alliteration remains the goal. Here's what it is: the single most insulting maneuver in sports, a snarling, domineering show of force, a reminder that not only are the 24 square feet of the batter's box Juan Soto's but so are the 17 inches of width and whatever variable height the umpire determines to constitute the strike zone.

The shuffle is the apex of Soto's mind games -- mostly performative, though the performance is quite magnificent. He unleashes it when he takes a pitch close to the strike zone for a ball. Most of the time, Soto will lurch forward with his right leg, then drag his left leg behind while tilting his head toward the mound and stink-eyeing the pitcher. Sometimes it's more of a squat than a dead-leg. Other times he'll offer a little hop. The Soto Shuffle is versatile. It contains multitudes.

The original germinated in the low levels of the minor leagues. Soto dominated rookie ball, winning the Gulf Coast League MVP award, so the Nationals sent him as a 17-year-old to play in the short-season playoffs against teams laden with college players. He hit .429 in six games. Soto started the next season in low-A, an aggressive assignment during which he started shuffling.

He was facing a hard-throwing prospect. He needed a mental edge. He punctuated pitches outside the strike zone with the little hop. His teammates were giddy -- and fearful that Soto was making himself a target for opponents. Whether it was youthful hubris, beyond-his-years know-how or perhaps both, he responded: "I don't care." Eventually, the jump would evolve into more of a foot-drag, but he wouldn't stop.

"It's just part of my game," Soto says. "I'm just trying to pump myself up, try to help me out. It's tough to hit those balls. I just let them know, it's tough, but I'm here to get it."

“Once you learn about Juan and talk to him and see what he’s about‚ you almost respect him more for how he goes about every at-bat. He makes everyone better.”

- Nats first baseman Ryan ZimmermanHe kept getting it, hitting .360 as an 18-year-old with Hagerstown in 2017, impressing even those he insulted. Pitchers wanted to face Soto. They didn't know the shuffle was anomalous, antithetical to the person doing it. They didn't care, either. His actions were speaking louder than his words could -- soon enough, Soto had added a crotch grab to the shuffle -- and they relished getting a chance to shut him up.

When JoJo Romero, a hotshot left-handed pitching prospect in the Philadelphia Phillies organization, faced him for the first time, Soto shuffled his way to a walk. The second time through the lineup, Romero struck him out looking on a slider.

"You feel that intensity just making eye contact," Romero says. "He's a big eye-contact guy. He looks at his opponent. He does the shuffle. His presence in the box is intense. You know when you're pitching to him you can't make a mistake."

Two days later, Romero posted a video on Instagram of the strikeout pitch. Soto saw it. And he made a promise to himself: He would get his revenge.

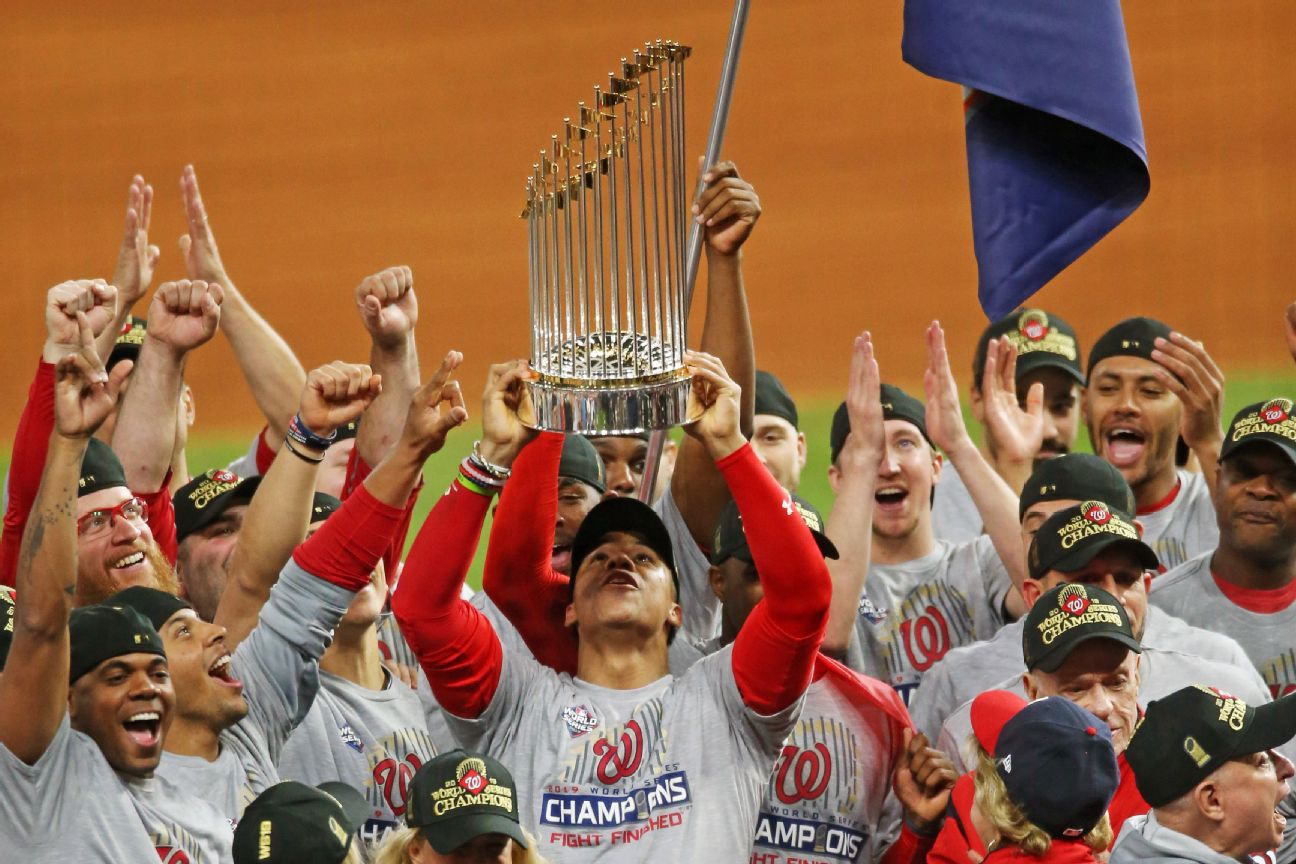

In the Nats' first-ever World Series appearance, Soto was the third-youngest cleanup hitter ever -- and went 9-for-27. Thomas B. Shea/USA TODAY Sports

NEVER, IN 2019, was Juan Soto better than when he worked ahead 2-0 in a plate appearance. His .377 batting average after 2-0 was his best after any count. He got on base nearly 64% of the time and slugged .812. And now Gerrit Cole had put Soto right where Soto wanted to be.

He was still looking fastball. Cole wasn't going to give it to him, though, not after what happened to the last one. Another curveball, this one 85 mph, up and away again. Soto didn't bite. He did, however, shuffle.

Soto's ability to track pitches is a God-given skill on par with his bat-to-ball ability. He can draw walks at an elite level while still striking out sparingly. During spring training in 2018, that realization alerted those at the major league level he was worth watching, even though he was just 19 years old. Chip Hale, then the Nationals' bench coach, flagged down hitting coach Kevin Long after watching a spring game. Soto's swing, Hale said, was a thing of beauty.

Long was in his first season with the Nationals after serving as hitting coach for the New York Yankees and New York Mets. He knew of Soto's batting average in Hagerstown but wondered if it was born of a small sample after a fractured right ankle had sidelined him for most of the season. One gander at Soto in the batting cage answered that.

When Long scouts a hitter, he starts by looking at his base -- how wide his legs are, how much flexion they have. Soto's setup looked powerful, especially after he filled out and was packing 220 pounds onto his 6-foot-2 frame. He set up his hands just off his back shoulder, near the hitting position, eliminating excess movement. His hips rotated with cleanliness and urgency, drawing power from the ground into his trunk, and his ability to keep his torso from joining them created a rubber-band effect, supercharging his swing with even more force. When the barrel of the bat flared into the zone, Soto's head barely moved. Long couldn't believe it. He had worked with some of the best hitters in the world. And this teenage kid had the most efficient swing he had ever seen.

Soto played in five games for the Nationals that spring. He homered, doubled, drove in five runs and posted a 1.232 OPS. Washington returned him to Hagerstown anyway, content to slow-play his ascent.

"I remember that day," Soto says. "I cried that day when they told me that, because I ... worked on myself. I worked on my body ready to come play higher. And they told me, 'Hey, you can do whatever you want, you're going to start low-A.' And I cried, right in front of them. I'm like, 'Why?' They're like, 'Don't worry. We just want you to play 130 games. I don't care if you play rookie ball or you're playing in the big leagues, but we want you to play 130 games and you're going to start in low-A.' It made me more hungry and wanting more. And that's when everything started going."

The Nationals didn't know Soto had come into that 2018 season determined to make the big leagues by September, but they had already seen his capacity to master stretch goals. When Soto was a kid, his mother, Belkis, had sent him for English lessons. He begged her to stop. "I don't need English to play baseball," he said. She told him baseball players spoke English. "No," he replied, "they just play baseball."

Playing baseball, he learned shortly after signing, constituted much more than hitting. When team meetings were held in English and he struggled to understand, Soto put in extra work on the Rosetta Stone app the team provided players from Latin America. When he wanted a trial run of practical use, he went to McDonald's, ordered food and listened to others. He insisted teammates speak to him in English. If he could hit a triple-digit fastball, he figured, English would be a breeze.

Fluency took Soto about a year and a half. His ability to pick up the nuances of the language gobsmacked the Nationals at first, though they were beginning to understand the essence of Soto: His brain's ability to process massive volumes of information was unique. He wasn't just a hitting savant. He was like a supercomputer, capable of coupling learning with application.

That spring, as spin rate on pitches was beginning to become a more widely recognized element around the game, Soto had moved on to the next level, talking with coaches and teammates about the spin axis of breaking pitches and how it affected their shape. He spent 16 games in Hagerstown, batting .373/.486/.814 before the Nationals promoted him to high-A Potomac. Fifteen games later, having hit seven home runs and OPS'd 1.256, he left for Double-A. There, DiPuglia visited to get a look at Soto, at just how real this was, and even he struggled to understand. Just four years earlier, Soto was all potential and dreams and unfulfilled talent, and now, as DiPuglia looked at Nationals field coordinator Tommy Shields, he was the sort of player who befuddled a scout who had spent the past 30 years answering the very question he was now posing rhetorically.

"Tommy," DiPuglia said. "What is this?"

During the 2019 regular season, the 20-year-old Soto hit 34 home runs, more at that age than Mike Trout and Mickey Mantle and Ted Williams. Mary Beth Koeth for ESPN

IT WAS THE meteoric rise of a player who would lead the Nationals to their first World Series, to this October night. As Cole cycled through the options for his fourth pitch, the crowd at Minute Maid had gone from deafening to dead. Soto's presence doesn't just burrow into the head of the pitcher. It can metastasize through an entire stadium.

Soto was still looking fastball and, at 3-0, had the green light to swing away. Cole feathered in a slider for a strike, eliciting a lunge but no shuffle from Soto. He had become comfortable in these sorts of at-bats, a weathered veteran at age 20, grizzled by years of bystanders more inclined to stomach his precociousness than oblige it.

Just a couple of months after Soto cried about his designation to low-A, happenstance made his major league call-up a necessity. On May 19, 2018, with outfielders Adam Eaton, Victor Robles, Brian Goodwin and Rafael Bautista already out injured, Howie Kendrick tore his Achilles. As Kendrick lay on the warning track, being tended to by trainers, Rizzo had already made up his mind: The Nationals would call up Soto the next day.

Rizzo had experience in this space. He summoned Bryce Harper at 19. And he had a personal connection with Soto, having accompanied DiPuglia to the D.R. to meet him before giving the 16-year-old the biggest deal he'd ever given a Latin American player in his two-plus decades doing deals there. Still, less than a month earlier Soto had been in Hagerstown. He'd never played left field. Even for Rizzo this was a stretch.

On May 20, Soto arrived, pinch hit and struck out. The next day, he was starting in left and batting sixth in a lineup that featured Turner, Harper and Anthony Rendon at the top. He hadn't slept much the night before. Soto, so unflappable, was nervous. He started to look at videos of the first at-bats of players he admires, like Ronald Acuna Jr.

"Most of the guys I look for," Soto says, "they always have gum in their mouth, and I'm like, that's a good idea."

He chewed one piece, then two, then three, then four. Still not enough. Five, six, seven.

"And then I look at the eighth," Soto says, "and I'm like, should I need it? And then I grabbed my chest and I'm like, yes, I need it."

“I’ve seen guys get locked in‚ but never at this young of an age. It’s unique. We have one of the best hitters I believe that’s ever played the game. To be a part of it and to watch it every day‚ I’m blessed.”

- Nats hitting coach Kevin LongHe stepped from the on-deck circle to the plate and remembered where he was: exactly where he belonged, in those 24 square feet, his sanctuary. The box here was no different than at Niche's field, in Fort Lauderdale, at Hagerstown or Potomac or Harrisburg. The box does not care about age or inexperience. It is the most egalitarian place in the universe.

Soto's intuition kicked in. He hunts for tells with the fervor of a poker player, for the slightest tip of what might be coming, and even when a pitcher doesn't offer that, he has a propensity to deduce pitch type and location. Here, he figured since the San Diego Padres didn't know him, they would feed him a first-pitch fastball, middle-away. What they also didn't know is Soto craves middle-away fastballs. When Robbie Erlin threw just that -- and when this one landed 422 feet later in the left-center-field stands -- so began a historic run.

The success was immediate enough that Washington never considered sending Soto back from whence he came. All of the admirable qualities were plain as day: the curiosity, the ambition, the talent, the professionalism. Soto's pregame routine staggered veterans. Every day in an indoor batting cage, he sets up a tee low and close to him and shoots 10 line drives to the opposite field. He then moves it to the outside corner and fires more the other way. He doesn't thirst for launch angle or elevate to celebrate. From his arrival, Soto was uncommonly disciplined and confident that his swing needed only repetition -- that it would do to major league pitching what it had done in his limited minor league time.

As odd as Soto's drills appear -- in one, Long flips him a ball, and he jabs his hands toward it and pokes it with the bat's knob, and in another, he rotates his body 90 degrees inward, as if his back were to the pitcher, and swivels his hips to hammer the ball toward the second-base bag -- they work. He is so attuned to his swing, to its health, that Soto need not see where a ball goes to know if he's right. He listens to the crack of the bat. It is so distinct, and his swing so dialed in, that if the sound is hollow, he'll grab fresh lumber.

Teams quickly figured out that Soto feasts on fastballs and switched him to a diet of off-speed pitches. To counteract that, Long introduced Soto to a pitching machine that feeds breaking balls. Soto would stare at some to familiarize his eyes with the spin and swing at others to ready his body -- hundreds of reps a day of self-assigned homework, like with the Rosetta Stone app. Soon thereafter, he became one of the best breaking-ball hitters in the game.

Which should not have been much of a surprise. Soto wound up with 494 plate appearances in 2018. Only 11 players in the previous century had earned as much playing time in their age-19 seasons. None finished with an OPS as high as Soto's .923. Hall of Famers Al Kaline and Robin Yount didn't muster .700. Hall of Famers Ken Griffey Jr. and Mel Ott fell short. Not even Harper, Soto's teammate, the most hyped prospect in a generation, had done what Soto managed to after a rushed call-up.

What is this? The Nationals and all of baseball were only beginning to understand.

HERE'S WHAT IT takes to defeat Juan Soto: an aberration. It takes someone like Gerrit Cole, whose average fastball velocity lives at the upper bounds of the intersection between performance and health. The threat of his fastball perpetually lurks, burrows itself into the brain of a hitter, even one as cocksure as Juan Soto.

He was looking fastball again, after slider-curveball-curveball-slider, and when Cole unfurled a 90 mph changeup, Soto swung right over it. Strike two. As he retreated from the box, he nodded once, twice, three times, four times -- never locking eyes with Cole, but willing to acknowledge that he'd just been owned.

This was respect. Well-earned respect. Cole had last thrown a 3-1 changeup on April 3, more than 30 starts earlier. In the time between, he had faced 54 counts of 3-1 and not once offered up his change. Baseball is a long game, not just in time but in the ability to spend an entire season setting up the perfect moment.

Much of what Soto did in Year 1 with the Nationals was in service of Year 2. The most difficult part of playing baseball, he says, wasn't the baseball. It was the realization that everyone wanted something from him -- time more than money. It was learning to say no when his instinct is to always answer yes. Even now, when Long texts Soto, he replies immediately. Not only does Soto get back to DiPuglia quickly, he typically does so via FaceTime.

He doesn't want to forget where he came from or who he is, to get so consumed in his alter ego in those 24 square feet that he loses himself in the infinite rest of space. Bifurcating those identities matters.

Around baseball, players talk with Soto before and after games and find him charming and kind and magnetic, and there's always a slight cognitive dissonance because of who he is inside the box -- and, now and again, slightly beyond it. Part of Soto's preparation includes taking a mock at-bat from the on-deck circle, swinging with every pitch thrown to the batter ahead of him. Sometimes, before innings, he will sneak behind the plate for a better perspective, a breach of protocol capable of enraging opponents even more than the shuffle.

"I've told him 10 times," Turner says, "'Hey, man, I wouldn't do that.' And he still does it. He doesn't care. He's not trying to disrespect anybody. He's trying to win that at-bat. And I understand why pitchers are mad and rightfully so, but he's doing his thing and he's locking it in. So they better be ready to compete because he is.

"He's greedy in a very good way."

With that greed comes greatness, and it manifested itself in his first full year. During the 2019 regular season, the 20-year-old Soto hit 34 home runs, more at that age than Mike Trout and Mickey Mantle and person to whom he is compared most often these days, Ted Williams, whose nickname was The Greatest Hitter Who Ever Lived. In the wild-card game, Soto smashed a 97 mph fastball for a single off super-reliever Josh Hader to score the winning runs and vanquish Milwaukee. In the division series, he hammered a game-tying home run in the eighth inning of the deciding Game 5 off future Hall of Famer Clayton Kershaw.

The National League Championship Series handed Soto the stage he warranted, and in the first game he stepped to the plate against Miles Mikolas, a veteran starter, with the bases loaded. He was shuffling, and he was going full hand-on-the-junk adjustments, and when Soto rolled over a ground ball to end the inning, he was greeted with a copycat: Mikolas staring at Soto and grabbing his crotch. Soto nodded, just like he would after Cole's changeup. Game respects game.

If he didn't do that sort of thing -- if Soto's shtick were completely one-sided -- perhaps all of his teammates' fears of baseballs screaming toward his earhole would be more founded. Since Soto debuted, he has been hit by a pitch just four times, 338th in that span. Opponents don't necessarily seek physical reprisal with Soto. They want to beat him. Ryan Zimmerman, the longtime heart of the Nationals, noticed it in the NLCS. Cardinals starter Adam Wainwright, like Zimmerman a tenured veteran, walked with a pep in his step when he retired Soto. Here was a 20-year-old, still a few weeks from being able to drink legally, extracting a different level of competition from a player who was old enough to be his father.

"That's what baseball needs," Zimmerman says. "Once you learn about Juan and talk to him and see what he's about, you almost respect him more for how he goes about every at-bat, the competitiveness. He makes everyone better."

"When he's in that box, he feels like his best version of himself," says Nats shortstop Trea Turner. "And that's where he can be himself and just have a lot of fun." Mary Beth Koeth for ESPN

THE FASTBALL NEVER came. For six consecutive pitches, Gerrit Cole, who in 2019 had the best heater in the world, went off-speed. And because Cole was Cole, those weren't exactly slop. The last one was a slider on the outer third and lower third of the plate, the sort that might vex a hitter who doesn't spend every day swinging at pitches on a tee and looking to drive them to the opposite field.

Soto had exaggerated his crouch and lost the pointed front toe, anchoring himself to the ground. It's a conservative two-strike approach in a world where strikeouts have mushroomed to cartoonish levels and players such as Soto -- who finds himself atop slugging leaderboards and near the bottom of strikeout rates -- are all but extinct.

He swung at this pitch, well located, at 90 mph obscenely hard for a slider, not with some protective chop but the full Juan Soto treatment, with damage on the mind. Cole's neck whipped toward left field, just in time to see the ball ricochet off the wall for a double, scoring two runs. In his career, Cole has gone at least six pitches with more than 1,100 hitters. Only once before had all six been off-speed. On this day, not even the aberration could stop Soto from winning.

Soto's story doesn't end after the Nationals win the 2019 World Series, of course. He missed the first two weeks of the 2020 season after what he believes was a false positive for COVID-19 kept him quarantined. When he returned, he was the best hitter in baseball, and it wasn't particularly close. In 47 games, Soto won the NL batting title hitting .351 with a .490 OBP and .695 slugging percentage. His OPS was nearly 100 points higher than that of any 21-year-old in baseball history. He walked 41 times and struck out only 28, numbers from a bygone era.

"I've seen guys get locked in, but never at this young of an age to have it this figured out," Long says. "It's unique. It's something that we may not see for a long, long time. It's something that will continue I think for a lot of years. And we have one of the best hitters I believe that's ever played the game and someone we can watch and say, wow, this is maybe how hitters should hit.

"To be a part of it and to watch it every day, I'm blessed and fortunate to be able to see this because it's really, really one for the ages."

Even in a disappointing season for the Nationals, Soto found new ways to entertain beyond the gaudy numbers. Remember JoJo Romero, the left-handed prospect with the Phillies? He made the big leagues in 2020 and had turned into a cult favorite in Philadelphia, chugging a Red Bull and crushing the can on his arm before every relief outing.

On Sept. 22, he entered the game in the bottom of the third inning with two runners on, specifically to face the left-handed hitter at the plate: Soto.

"I waited since 2017," Soto says, "all the way to 2020."

On the first pitch, Romero left a fastball over the plate. Soto destroyed it to where nearly all of his best home runs go, left-center, a place that doesn't look as pretty as a parabolic, pulled homer but demeans and demoralizes pitchers even more.

"The first pitch I see, I just hit it as hard as I can," Soto says. "I just remember all this stuff he's done. I'm like, now you're going to see this all posted in the media. And it's just great. I mean, things like that, I just wait to happen. I don't mind if you get me, but I'm going to get you one day."

In the dugout afterward, Soto's teammates noticed his glee. They asked why he was so giddy.

"It's like the most happy vengeance ever," Turner says. "He just wants to battle. He doesn't hold it against the other guy, he doesn't hate the other opposing player. After the at-bat's over, he can laugh, he can smile and he can say, 'OK, you got me. But next time I'm coming right back for you.'"

It is the benefit of owning those 24 square feet, of carving a path alongside Ott and Mantle and Trout and Williams. Soto gets to write his story. He can appreciate why Nationals fans panic when he leaves a spring training game early as he did Thursday, with a slight tweak to his calf that prompted a precautionary exit but shouldn't cause him to miss games. He can spend his winters traversing the D.R., learning about his homeland and all of its natural beauty, and he can focus on the elements of his game he wants to improve, like his speed, which he did this winter, whittling his 60-yard dash to an elite 6.5 seconds. He can learn more about adulting in conversations with Turner and Zimmerman, picking their brains about the stock market, and he can enmesh himself more in the D.C. community, spending time spreading his Juan Soto-ness to area kids. In 2019, when the Nationals were going to release a bobblehead with Soto sneering, he asked the team to redo it. He wanted to be smiling. When he looks in the mirror, he sees the other 23 hours, 45 minutes a day.

Then Soto saw his old friend Tatis sign a 14-year, $340 million contract with the San Diego Padres this winter and wondered what it meant for him. Tatis plays shortstop, Soto a less valuable position in right field. Soto is a generational hitter in a game that pays for power, pays for patience and pays exorbitantly for those with both. Tatis nabbing that lofty a sum four years before free agency got people in baseball talking: What could that mean for Soto after the 2024 season? The number would seem to start at $400 million. It could exceed Trout's $426.5 million. If Soto doesn't sign a lifetime deal with Washington and hits the free-agent market at 26 years old, in the prime of his career, could it possibly reach $500 million guaranteed?

"If I get something like that, it's going to be a lot of people in a good spot," Soto says. "A lot of people around me [are] going to get helped by that money. That was the only thing that I think. I believe in God and he's always talking about give love to the people that you love and help the people, help the world, whatever you can. And that's how my mom and my dad helped me out with it, just trying to help people. For me, that's the only thing that gets to my mind when I hear about all the money."

Soto has time to figure it out, though he knows better than most how quickly it moves. There will always be more battles to win, more competition to slay, more happy vengeance to exact. Occasionally it will come standing on second base after subjugating the best pitcher around in a six-pitch at-bat, wearing the scent of victory, smiling as he does so often outside the 24 square feet.

What is this? History unfolding.

Wardrobe styling by Mila Kastari; Set and prop styling by Lisa Gigliotti; Grooming by Alaina DeBernardis; Production by Kim McEniry/Overflow Productions; Suit Jacket by Boglioli Milano; hoodies, joggers, shoes, long-sleeve shirts by Under Armour; Knit polo by Lanvin