Paul George comes home

The Clippers' star went to L.A. to team up with Kawhi Leonard and play in his hometown. But there was one more motivation much closer to his heart.

The call came in the middle of dinner. Paul George had been text-messaging throughout the meal — not an uncommon occurrence at this point in late June, as the NBA approached one of its most audacious free-agent signing periods. But when the call came in, he got up from his table at Catch LA, an upscale seafood restaurant, to take it privately.

That's when his friends knew something was afoot.

"I knew it was something. Something big," says Alex Jackson, George's best friend from high school. "Because I can kind of tell with him. He gets quiet, looks around because something is on his mind."

The caller on the other end of the line was Kawhi Leonard, the soon-to-be free agent who had just won his second NBA Finals MVP award in leading the Toronto Raptors to the title. Now he and George were surreptitiously discussing joining forces on a new team, the LA Clippers, a move that might reshape the balance of power in the NBA for years to come.

It would be an incredible turn of events — nearly inconceivable in its complexity and degree of difficulty. George was under contract to the Thunder for two more years. "It just didn't seem likely," George says.

But nothing is impossible in this era of player empowerment in the NBA. Leonard and George had both come into the height of their powers — and leverage — at the exact moment that their hometown team had been positioning itself to take advantage of it.

When he rejoined his two friends, Jackson and Myles Williams, at dinner that night, George tried to keep things to himself. They were the types of friends who knew not to ask.

"But after a little bit," Jackson says, "he was like, 'I gotta let it out, man.'"

I think I'm going to come home.

"P definitely keeps that one mood," Williams says. "But deep down inside, I knew he was excited."

If George and Leonard could pull this off, the Clippers would become an instant title contender. But it was more than that for George. A lot more than that.

"[People] think it was a basketball move," George says. "And for a lot of reasons, it was a basketball move. But that's not where it comes from.

"It was a lot deeper than me coming here for basketball reasons."

Ramona Shelburne helps tell the story of why Paul George decided to join the Clippers and how close he is with his family. Produced by Mike Farrell; edited by Kevin Burns.

THE BATTLE FOR L.A.'s basketball soul hasn't really been much of a battle until now. The Lakers have 16 titles and a veritable Mount Rushmore of Hall of Famers. And the Clippers have ... also been based in Los Angeles.

But this is a real rivalry now. As soon as the 29-year-old George and 28-year-old Leonard teamed up on the Clippers — the partnership became final on July 6, when Leonard signed with the club and George was traded to it — you knew the Lakers and Clippers would be positioned as the marquee game on Christmas Day.

It is a taut game throughout, with Leonard and George trading haymakers with LeBron James and Anthony Davis. But the Clippers rally in the final minutes to nip their more glamorous rivals 111-106.

George lingers on the Staples Center court long after the game, soaking in the atmosphere.

Fans congregate by the tunnel leading to the Clippers' locker room, the group swelling as red-coated security guards try to keep them from blocking George's path.

It could have been uncomfortable, with fans pushing and shoving to get his autograph or capture some other piece of him. But a collective understanding has taken hold of the crowd. Paulette George's wheelchair is in the tunnel, but she and her husband, Paul George Sr., are still four rows up in the stands.

In full uniform, George goes to his mother, wraps his arm around her, shielding her from the crowd, and helps her walk slowly down the stairs.

No one touches them.

"I think the fans ... they get it," George says. "And they allowed for me to have that moment with my mom."

George has always been close to his mother. As a kid, he was her "sidekick," he says, holding her hand as they went on errands around Palmdale, California. She called him "Man" because he was bigger than all the other kids his age, and because, of her three children, he was her only son.

"My mom was everything," George says. "She made sure the house was organized, made sure our homework was done. She was the enforcer. My dad is more like me, laid-back."

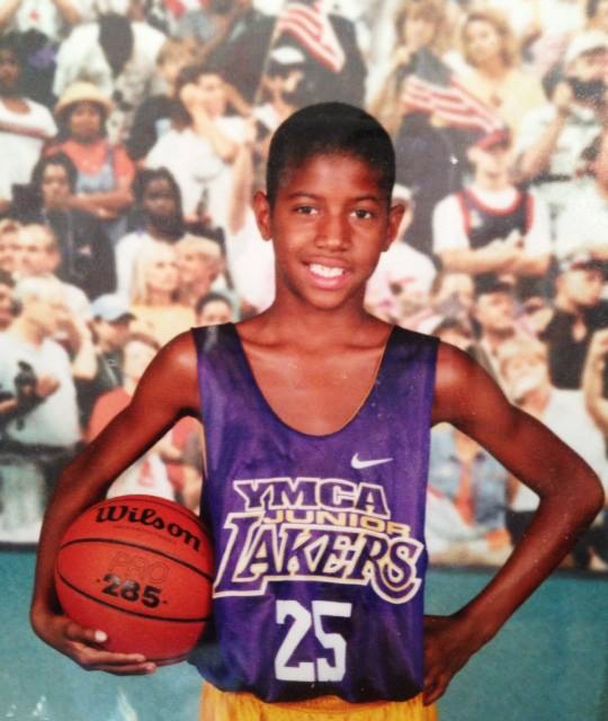

George grew up a Kobe Bryant fan in Southern California, close with his mom (she called him her 'sidekick'), dad and two sisters. Courtesy George Family

Then one night she got a bad headache, and everything changed. A blood clot had traveled up from her calf, cutting off oxygen to her brain and causing a stroke. She was 36 years old. Paul was 6. He was outside playing basketball when the ambulance pulled up and carried his mom out on a stretcher. He was terrified.

"She was almost at, like, a vegetative state," George recalls of the early days in the hospital. "She was unrecognizable, she couldn't communicate, she couldn't talk, she was going blind."

Paulette could hear everything happening around her but couldn't talk or move. Eventually, she learned how to communicate in other ways.

"She would put her hand up, and the doctors would tell her to squeeze it, squeeze her hand," George says. "That was enough for me. I knew she was aware. She was still with us."

It took years of constant therapy to relearn how to walk and talk. During one of her stays in a rehabilitation facility, she developed a high fever caused by pneumonia and nearly died.

"My mom is all about defying odds, because odds was stacked up against her," George says. "They said my mom wouldn't walk again. They said my mom wouldn't talk again. They said she would be completely paralyzed, that her vision wouldn't come back. And she defied all of that."

Paul Sr. worked two jobs to provide for the family while his wife recovered. Older sisters Portala and Teiosha stepped up to help raise their brother. By the time Paul was a freshman at Knight High in Palmdale, his mother was able to attend his games. Knight High equipment manager Jimmy Segura put a special chair on the court for her, where she'd sit with Paul Sr.

"They came to every high school game," Segura says.

It was still difficult for Paulette to move around. But her children gave her motivation to push herself. The way to regain her independence and abilities was to keep trying to do as much as she could. Walk up a few stairs, even if it took 10 minutes. Have Paul Sr. park the car a little farther away. Walk rather than use the wheelchair. Cut every article written about Paul out of the newspaper, then put them into a scrapbook.

Simple tasks, taken away by her stroke. But so precious once she regained them.

When Paul went to Fresno State for college, his parents moved from Palmdale to Fresno — about three hours north — so they could keep going to his games. But when Paul was drafted by the Indiana Pacers in 2010, traveling to his games got considerably harder.

"My mom doesn't complain," George says. "But having conversations with her, it's hard for her to get on planes and travel.

"For me to be able to come to her and make it a lot easier for the travel on her and my dad, that was one of the biggest reasons I wanted to come back and play at home."

AFTER THE NEWS conference when the Clippers introduced George and Leonard, coach Doc Rivers walked with George through the audience, and a theme quickly emerged.

"It was funny," Rivers says. "One George, two George, three George. Holy cow! His sister, sister's husband, his dad, his mom ... and they're at every event we've had. They're all there."

There are even Georges around Paul George who aren't related to him. There's his security guard, Vincent George, whom he met in Oklahoma City. "He calls me Unc," Vincent George jokes. There's "Coach George," the assistant coach from Knight High in Palmdale, who taught him to dunk by jumping over trash cans. "My name is actually J-O-R-G-E Swayne," the coach says with a laugh. "But he just calls me Coach George."

It's a lot. And to some — including George's coach — it would be a distraction.

"Like, I love Chicago," Rivers says of his hometown. "But I have no interest in playing there. No way — all the people, the ticket requests."

But George prefers it this way.

"[He] actually wanted to come home and to dive into the distractions instead of running away from them," Rivers says.

In Indiana, George had a house right on Geist Reservoir, where his friends and family stayed, fishing while he was at practice, then frying up whatever was caught for dinner. George kept in touch with friends via text message and nightly video game sessions.

But those visits and virtual hangouts aren't the same as living in the same city. And after nearly a decade away from home, George's friends could sense him yearning for that support.

"We didn't get to see him a whole lot," says Dallas Rutherford, one of George's closest friends. "We'd go fly out there, but obviously we're all older and have our own lives. So it's not like we can be out there 24/7."

Now, in Los Angeles, George has about 70 relatives who regularly come to events, games or family gatherings. There is an even larger group of friends who are now able to show up and support him too.

"I think he's at that point in life where he was like, 'I know who my friends are. I know who came to visit me in Indiana. I know who came to visit me in Oklahoma,'" Williams says.

"Like, 'These are my people.'"

ESPN grooming by Erin Svalstad; production by Mary Brooks/3Star Productions Joe Pugliese for ESPN

IN AUGUST 2014, George saw firsthand what it could mean to be surrounded by the people who mattered most to him. In Las Vegas for a scrimmage with Team USA, he suffered a career-threatening broken leg when he landed awkwardly trying to block a shot.

His mom was there — she had been able to make the four-hour drive with George's dad. She walked down from the stands at UNLV, across the court and into the ambulance that took him to the hospital.

"I needed that, honestly," George says. "I was in so much pain. I was in so much disbelief. I was in so much shock. I was immediately in a depressed state of mind of, 'How could this happen?'"

It was his mom who reassured him throughout the ride to the hospital — and well beyond.

"The thing that kept registering in my head was, 'If my mom could get through what she got through, then this should be a cakewalk,'" George says. "Seriously. On the darkest of days, where I was just out of it — mentally, physically — it was like, 'Pull yourself together. My mom has been through worse. You got it. Just push through.' That was where the motivation was coming from. From seeing my mom go through it."

It took eight months for George to return to the court, the occasion big enough for his family to make the trip and watch Paul score on his first shot and finish with 13 points in 15 minutes of play in the Pacers' win against Miami. By February 2016, he'd gotten back to All-Star form, but when the Pacers lost in the first round of the playoffs that year (to the Raptors) and the next (to the Cavs), George felt as if his time in Indiana was coming to an end. He wanted to return to Los Angeles as a free agent in 2018. The Pacers began to look for a trade before they would lose him as a free agent for nothing.

“The thing that kept registering in my head was, ‘If my mom could get through what she got through, then this should be a cakewalk.’”

- Paul GeorgeThe Lakers were an early contender. George's interest in joining the team had already been reported, and after all, this is a kid who grew up an hour from downtown L.A. idolizing Lakers legend Kobe Bryant. But the Lakers opted not to trade away their young players to acquire George just a season before he could join them as a free agent.

The Thunder swooped into the void, trading for George even without the assurance that they could keep him long term. For OKC, the risk of losing George to the Lakers in a year was worth it. George replaced the departed Kevin Durant and served as an enticement to keep star point guard Russell Westbrook happy. Plus, Westbrook and the Thunder figured the season would be like a yearlong recruiting visit to persuade George to stay in Oklahoma City.

"That one year, Russ and P grew a great relationship," Williams says. "With Paul, like, if you don't mess up a trust with him, he's definitely going to be down for you 100 percent. And Russ had his back no matter what."

So as a free agent the next summer, George felt more connected to the Thunder than most people expected. The idea of a homecoming to Los Angeles appealed to him, but he was a little miffed the Lakers hadn't traded for him the year before. He couldn't deny the bond and loyalty he felt to Westbrook and the Thunder, and he didn't want to give up on the team after just one season. George re-signed with the Thunder, a four-year, $137 million deal, without even meeting with the Lakers or any other team.

"He kept that really quiet," Alex Jackson says. "I didn't even know he was going to [stay in] OKC until he told me that I was going to come on the flight to the party where they announced it."

And that's likely where he would have stayed if Leonard, during his own free-agent process in 2019, hadn't floated the idea of joining forces.

The pairing of Leonard and George started with a simple phone call after the Raptors' championship. "It was congratulating him on winning," George says. "That's how it started ... then it took on a life of its own." Andrew D. Bernstein/NBAE/Getty Images

IT STARTED INNOCENTLY enough, with George calling Leonard — whom he'd known since their high school days in Southern California — a few days after the Raptors won the championship.

"It was congratulating him on winning," George says. "That's how it started ... then it took on a life of its own."

Once the two Southern California boys began talking, "it just trickled from there," George says.

There were countless text messages and phone calls and then two in-person meetings at Drake's house in Hidden Hills, California. (Drake had befriended Leonard during his season in Toronto and let Leonard — who lives in San Diego — stay there when he was in Los Angeles for free-agent meetings.) By July 1, they had decided to put their plan in motion: Leonard told the Clippers that he was interested in playing for them but only if they could improve their roster by adding an All-Star-caliber player like George.

The next day, Leonard met with George in Los Angeles. Shortly after their meeting, George's agent placed a call to Thunder president Sam Presti, asking if he would look for a trade to help George and Leonard play together.

Presti was stunned, but he said he'd consider it. His only request was to meet with George face-to-face before proceeding. He flew to Los Angeles on the evening of July 2 and saw George on July 3. George reiterated the request and talked through his reasons for wanting to make such a move — he wanted to play with Leonard but mostly wanted to play at home — just a year after re-signing with the Thunder.

It wasn't what Presti wanted to hear, but he respected the way George went about it. Presti said he'd look for trades that would help him play with Leonard and made sense for the Thunder.

Over the July Fourth holiday, the Thunder opened conversations with the Clippers and the Raptors. The Clippers were clearly the favored destination, and they were deeply engaged in creating a package that would net them George and Leonard.

The pair kept in constant communication, even meeting again at Drake's house after Leonard returned from a meeting in Toronto, according to sources with knowledge of the situation.

The Clippers weighed whether giving up promising rookie point guard Shai Gilgeous-Alexander, sharpshooter Danilo Gallinari and a historic haul of five future first-round picks was too much. At several moments, the deal nearly collapsed under its own weight.

"We were optimistic," George says. "But we were still unsure."

Eventually, the Clippers decided to pay the steep price. They weren't just getting George. They were ensuring that Leonard would pick them too.

George got word that the deal was complete from his agent. Then he called his parents.

"I can't explain what that feels like," George says. "As a kid, you see yourself and you envision this. I pictured my parents being able to watch me at Staples. I pictured playing in L.A. I pictured being an All-Star, a superstar.

"But I think the best thing is before every game when I'm introduced, 'Paul George from Palmdale, California.' I'm not playing for the Clippers. This is home. I'm playing for the home team."

"Growing up in Palmdale, I knew I loved the game. I didn't know how far it was going to take me," said George, here with his parents during a basketball court dedication in his hometown. Carlos Gonzalez/The1point8 for ESPN

IT'S DEC. 29, and Paul George is driving back to Palmdale, sick as a dog. The night before, he'd told reporters after a game that the flu "came out of nowhere. I was trying to leave everything out there, but honestly there was nothing in there for me to leave."

This is the kind of sick you don't get out of bed for, much less drive an hour and a half to attend an outdoor event in the dead of winter. But this event isn't something George could cancel.

His foundation has renovated three new courts at Domenic Massari Park in Palmdale and set up a free carnival. The mayor is coming. His old high school coaches and teammates are coming. Friends and family are coming. His parents are already on their way.

So George throws on a red sweatshirt, takes some cold medicine and drives the hour and a half north with his girlfriend, Daniela Rajic, and their two daughters, Olivia and Natasha.

It is freezing, with snow on the ground from a recent storm. Hundreds of people still show up to welcome him back.

Earlier in his career, George might not have embraced this opportunity as much as he has now. He was focused on establishing himself in the league. Growing his game.

"Had this situation approached me at Year 2, Year 3, I probably would have had this gut feeling like, 'I don't know how this is going to go, going back home,'" he says. "Going into Year 10, it seems the perfect time."

“Growing up in Palmdale, I knew I loved the game. I didn't know how far it was going to take me.”

- Paul GeorgeNow George is surrounded by familiar sights: The high-desert fields where he used to sprint with rocks in his backpack are covered by a foot of snow. Just around the corner is the Knight High gym, where coach Tom Hegre threatened him with extra sprints if he didn't shoot more. Down the road is his old house, where his older sister Teiosha dominated him in one-on-one games until he was in high school.

George grew up playing on the courts at this park. Now they would be named after him.

"I used to come here every day after school and play and work on my game," he says. "I had my first field trip in elementary school here, my first YMCA practices here."

George's voice cracks a few times as he relives the journey back home.

"I wanted to come back here. I wanted to improve it. I wanted to just give more everlasting memories that can live on further than I will," he says. "Every accomplishment, all my successes, I think this is probably the thing that I'm most happy about."

Paul Sr. is in the front row of the crowd, dressed from head to toe in Clippers gear. Paulette is next to him, cold from the snow but beaming with pride.

His daughters are backstage with their mother, in matching furry pink jackets and sequined shoes. George says he wants to retire as a Clipper — which means this will be the place they grow up too.

"Growing up in Palmdale, I knew I loved the game. I didn't know how far it was going to take me," George says, looking out into the crowd, smiling at all the familiar faces.

"What I wanted to get to in my career," he says, "is being back home. Being close to my people."