Deshaun Watson is ready to be heard

After a summer of change and fresh off a big-money deal, the Houston Texans QB is lifting his voice.

Deshaun Watson is asked a question -- What unique challenges does a Black quarterback face when deciding to speak up on social issues? -- and he begins to answer without thinking. It's as if a button on the jukebox is pressed, and the song enters the room. "I think you have to watch what you say sometimes," he says. "And I feel like --"

He stops, looks down, resets. He is not satisfied with the curated, focus-group answer he is about to give. His large hands slap his knees, and he looks back at the camera. Watson and I are 2,000 miles apart, connected only through technology, but I can see the layers being strip-mined as he reconsiders. The Houston Texans quarterback was ready to do what he's always done: say the right thing, be gracious and respectful and polite, conform to the standards of those who want to be entertained by his actions and made comfortable with his words.

"Honestly, I'm going to take that back," he says. "To keep it real with you, I feel like whenever a Black quarterback speaks up, the outside world sometimes doesn't think they're educated enough to know what's going on. So in reality, they're like, 'Hey, y'all Black quarterbacks -- shut up. Y'all don't know what y'all talking about.'"

His body language and his words convey a single sentiment: Enough. Enough with being judged, for as long as you can remember, by how you carry yourself and what you wear and whether you speak with requisite deference. Enough with fading into the background and issuing anodyne blandishments when someone publicly ascribes a failed late-game decision to the color of your skin. Enough with politely declining to comment when the man who owns your franchise suggests that players kneeling during the national anthem projects an image of "inmates" running "the prison." Enough with being told there's a right way and a wrong way and your way is always wrong. Enough with gratitude being mistaken for complicity, grace being defined as weakness, and money being viewed as insulation against injustice.

Enough with fearing that your voice will alienate the money and power that sits in judgment behind thick luxury-suite glass. Enough with being told you need to be educated before you address something the entire world can see with its own eyes.

Enough.

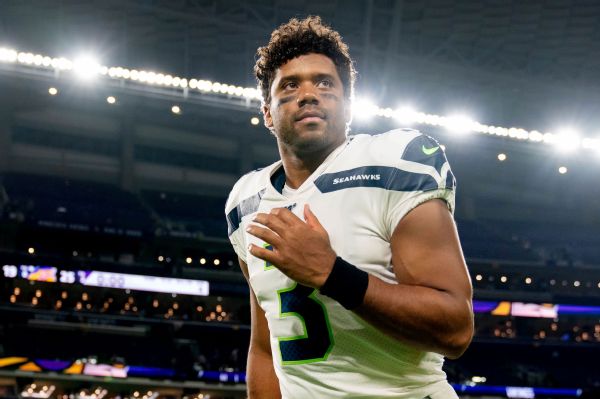

A BLACK QUARTERBACK (Kansas City's Patrick Mahomes) is the Super Bowl champion. Another (Baltimore's Lamar Jackson) is the NFL MVP. Watson, Russell Wilson, Kyler Murray, Cam Newton, Teddy Bridgewater, Dak Prescott -- there has never been a more empowered or talented group of Black men playing the most scrutinized and fetishized position in sports.

This offseason, in a culture flailing to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic and a police-brutality epidemic, these men have decided to risk public reproach -- from their league, the public, the president of the United States -- and speak their minds. On June 2, a week after George Floyd died when a police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly eight minutes, Watson spoke with his feet, marching with Floyd's family and several Texans teammates through the streets of Houston. They chanted, their voices bouncing off the hard asphalt and rising in the air. Watson made no public statements -- "I didn't have to say much," he says, "but just being there with the family and everyone in the city was a must" -- but his presence alone could be seen as perilous; before this spring, no Black NFL quarterback had taken a public stand against police violence since Colin Kaepernick began kneeling during the national anthem in 2016.

"It was sick for those policemen to sit there and know that this man is dying and he's yelling for his mom who's not even there," Watson says. "Speaking about it now, it's tough because it makes me angry for them to do that. ... I feel like we got to keep pushing forward to make sure everyone knows this is what's going on in the world and that it needs to stop -- and that it's going to stop."

Two days after the march, Watson appeared with Mahomes and other prominent Black NFL players in a video challenging the league to take racism more seriously. Titled "Stronger Together," the video was an unvarnished plea for the NFL to condemn racism and admit its error in shutting down protests. "How many times do we have to ask you to listen to your players?" Tyrann Mathieu asks the camera, in a tone that does not suggest he is awaiting an answer.

Commissioner Roger Goodell and the owners had been accustomed to setting the agenda on social justice, and now the ground was shifting beneath them. Think about what has happened in sports since the death of Floyd. The Confederate flag is no longer welcome at NASCAR races. The NBA returned with BLACK LIVES MATTER painted on the court and pleas for change -- league-sanctioned pleas, but still -- on the backs of jerseys. There were labor strikes during the NBA and WNBA playoffs after another Black man, Jacob Blake Jr., was shot seven times in the back by police in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Major League Baseball teams, of all unlikely entities, staged a rolling and somewhat disjointed labor strike of their own. Every NBA arena announced intentions to provide massive, safe polling places on Nov. 3, and many NFL teams -- including Watson's Texans -- have announced plans to do the same.

After the "Stronger Together" video was released, Goodell put out a new statement of his own, admitting -- too late, but still -- that the league was wrong about Kaepernick and saying that it will not stand in the way of on-field protest. Widely reported to be a key factor in Goodell's change of heart? The participation in the video of Watson and Mahomes. Now high-profile Black athletes -- even high-profile, alpha-male, leader-of-men, face-of-the-franchise Black quarterbacks -- are no longer holding back.

"I've known since high school that I just always had to do more, being a Black quarterback," Watson says. "I always felt like they labeled me and valued me a little less than the other guys, even if I was better." Matt Hawthorne for ESPN

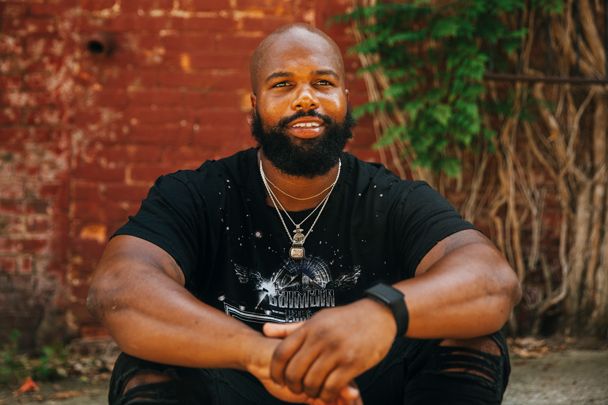

QUINCY AVERY, WATSON'S Atlanta-based private quarterback coach, began working with Watson his junior year of high school. "He's not the loudest or the most boastful," Avery says, "but you're immediately gravitating toward his energy."

Avery's father, Wendell, was a quarterback at the University of Minnesota, the former head coach at Savannah State, current receivers coach for the Toronto Argonauts of the Canadian Football League and the inspiration for his son's Black Quarterback Club. The club brings together retired quarterbacks like Warren Moon, current NFL quarterbacks like Watson and current college quarterbacks like Ohio State's Justin Fields. They tell their stories to quarterbacks as young as middle school, with the intent of educating them on the challenges ahead.

"There's no chance Colin Kaepernick faces the same things if he was anything other than a quarterback, right?" Avery says. "I think the NFL did exactly what it wanted to in not allowing Colin Kaepernick back in the league. They let every other Black quarterback know, 'You're the face of a franchise, and don't you step across that line.' It made a lot of guys very, very cautious and nervous about being able to step up and say the things that needed to be said. And now we've just reached a tipping point where it's, 'We don't care, we're going to say the things that need to be said.'"

“He always was very, very cautious in the things that people heard him say. You can hear it in the way he handles his interviews. ... He’s been doing it for so long it’s like breathing.”

- Quincy AveryIf Avery is right about the NFL's intentions, they worked on Watson. "I don't want to speak for any other Black quarterback, but honestly, that's why I haven't spoken up about that stuff," he says. "You've seen what happened. You've seen what Colin Kaepernick had to go through. You've seen what these other quarterbacks or other athletes, what they went through."

Throughout his career, Watson has been alleged to have committed a catalog of absurd offenses that never would have been leveled against a tight end or safety. After leading Clemson to a national title over Alabama in 2017, he visited the White House wearing a navy blazer, a red tie and a white dress shirt, yet he was criticized on social media because his pants were deemed too tight. Two years later, he went to midfield for the coin toss as the honorary captain for the title game between the same two teams. He forgot to pack his outfit for the game and borrowed a purple sweatshirt from teammate DeAndre Hopkins. A radio host in Nashville detected a lack of leadership in the sweatshirt. "You're not a corner or a WR," he tweeted. "You're a QB, you're a brand." It was pointed out that the sweatshirt was a Balenciaga -- price tag: $850 -- but a bar code is no match for a culture scorned.

"I know that's not racism on the scale of police brutality or things like that, but it's still racism," Avery says. "It's boiled down to they wouldn't say those same things about Deshaun if his skin wasn't brown."

The quarterback has become almost a totem within the sport, the mystic symbol called upon to provide spiritual guidance to the group, and Watson quickly became aware of how his position affected how others perceived him; how he dressed, how he behaved with his teammates, how he spoke. He started to lay his words down like tracks, a destination always in sight.

"I've known that since high school, and it goes back to being in a category that people put me in," he says. "I just felt that I always had to do more, being a Black quarterback, because from things like recruitment to camps, I always felt like they labeled me and valued me a little less than the other guys, even if I was better -- and everyone knew that. I always had to do more, and I've always felt that way --"

He stops for a split second as if to emphasize what he is about to say:

"-- until this year."

"He's not the loudest or the most boastful," says Quincy Avery of Watson, with whom he's worked since Watson was in high school, "but you're immediately gravitating toward his energy." Diwang Valdez for ESPN

THE TRITE AND facile description of Watson's evolution goes like this: the story of a young man who is finding his voice in these troubled times. The problem with finding his voice is that it's infantilizing, a verbal head-pat that suggests wobbly and uncertain steps toward an undetermined destination. Watson, more accurately, has stopped suppressing his voice.

His 24 years on earth have been lived in service of gratitude and conciliation. He is everyone's friend, facilitator, mediator, the one who sees similarities in the differences and common ground in the most uncommon places. His fourth-grade teacher in Gainesville, Georgia, Leslie Frierson, says, "He would sit back, observe situations and not be impulsive. He takes it all in and has a vision for down the road; I swear this was evident when he was 9."

There's a story they like to tell in Gainesville that typifies the Deshaun they know. In high school, he worked as a clerk for Hall County Judge C. Andrew Fuller. He was given a key to the office, and the judge made a point to inform the deputies who patrolled the courthouse that Watson was allowed to come and go as needed. On Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays during the football season, he finished practice and went straight to the courthouse, working until 10 p.m. He took Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays off, went to church Sunday morning and worked through the afternoon and evening, sometimes as long as 12 hours.

He did all this while winning a state championship and keeping an A average at Gainesville High. One day he was asked, "What do your coaches think of this schedule you're keeping?"

Watson, seeming surprised by the question, replied, "I don't think they know."

The stories of Watson's childhood are worn smooth. He started life in the Harrison Square Apartments, an unimaginative rectangle of public housing in Gainesville. Watson; his mother, Deann; and three siblings lived in 815, and its legacy lives on Deshaun's game-day wristbands. On Halloween night of fourth grade, Watson trick-or-treated at a church festival and came home with a flyer for Habitat for Humanity in his bag. His mom applied for a home, put hundreds of hours of service into the house while working two jobs and moved her family out of Harrison Square in a ceremony that was attended by then-Falcons running back Warrick Dunn.

Deshaun was a sophomore in high school when Deann informed him she had cancer of the tongue. "That was hard on Deshaun," says his aunt, Sonia Watson. "It was hard for Deann too -- to watch your son sit there and cry. But he made it through with prayer and all of us around him." Deann underwent treatment in Atlanta for nearly a year, and during that time Deshaun committed to Clemson and began referring to Dabo Swinney and the Clemson coaches as his "extended family."

But something else was happening beneath the surface. As the star Black quarterback for a state championship team in a football-mad town in semirural Georgia, Watson was scrutinized. "With my own school and inner Gainesville ... it stopped because of my football," he says. "But honestly -- it's a big county. The county schools and county area, they still looked at me the same -- a Black athlete from the hood that just happened to be better than everyone else [at football]."

Watson says the racism -- both overt and more micro-aggressions -- he experienced growing up was "definitely hurtful. But the way I grew up, and the way I saw it, it was kind of normal. So as a young boy, it was kind of like, 'I guess this is the way it should be.' And this is the way it has been for a long time."

ALL THIS EVEN while he was not just any Black kid from Gainesville; he was Deshaun Watson, superstar. His talent and his personality opened doors that remained closed to those without them. A street leading up to his high school was named after him before he took a snap in the NFL, and he lives with a sense of indebtedness that feels like the opposite of entitlement. It's a subconscious level of gratitude that serves as a barrier; he struggled to push back against the system because he benefited from it, and any criticism he might offer lands on the ears of the benefactors as a betrayal.

"He always was very, very cautious in the things that people heard him say," Avery says. "You can hear it in terms of the way he handles his interviews. The long pauses he gives -- I know he's initially thinking to say one thing, and then he has to calibrate it and figure out how to disseminate that same information to this group of people so that they won't take it the wrong way, or they won't perceive him as anything other than the elite human being that he is. Everything he did was very, very mindful. He's been doing it for so long it's like breathing."

In Week 8 of 2017, Watson's rookie year, it was reported by ESPN that Bob McNair, then the owner of the Texans franchise, told fellow owners, "We can't have the inmates running the prison," in reference to on-field protests by Black players. At the time, Watson refused to address the comments. Would he react differently today?

"Oh, definitely," Watson says. "I feel like everyone would. When we heard it, people were leaving the facility, saying they're not going to play this week, saying they're done playing the rest of the year, they're not playing for an owner that thinks that way. But they didn't really speak on it publicly like how things are getting spoken about now. I definitely would have reacted differently."

On the last play of a 20-17 loss to the Titans in 2018, Watson scrambled around and, with no time on the clock, completed a pass over the middle of the field. Lynn Redden, an East Texas school superintendent who was listed as his district's civil rights coordinator, took to the Houston Chronicle's Facebook page to write, "That may have been the most inept quarterback decision I've seen in the NFL. When you need precision decision making, you can't count on a black quarterback."

In a news conference a few days later, Watson was asked about Redden's comments. He thought for a moment -- watching now, you can see the tracks being laid -- and said, "That's on him. May peace be with him."

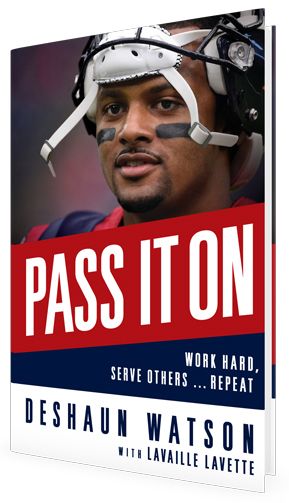

And as recently as January, in an ESPN Undefeated television special on the Black quarterback, Watson sat uncomfortably on a stage and said he doesn't talk about politics or religion because "you can't win." Even his just-released book, "Pass It On," walks gingerly, with noble but safe chapters such as "Ignore the Doubters, Forgive the Haters," in which he recounts the incident with the superintendent before concluding, "Most of all, I try to stop and consider all the love that's in my life, no matter what is going on in the moment."

But something clearly broke with the death of George Floyd, those seven minutes and 46 seconds etched into the minds of Americans, especially Black Americans, in a way that seems indelible. Watson says he considers what happened to Kaepernick to be "blackmail," and when asked if he's worried about possible repercussions for his own actions, he says, "Not anymore. And even previously, I didn't think it was going to do anything to cause my NFL career to stop. But now? For sure, no, not at all."

Any pretense of diplomacy is gone, the jukebox unplugged.

"I've always appreciated and really loved the people that loved me and helped me get to where I am," he says. "But I think for me to be able to speak about topics I never really talked about -- politics, social justice, religion -- I think I kind of broke through that barrier. It took me a while to break through that, for sure."

As Watson speaks now, his words sound liberating -- and still seem, from him, slightly illicit.

Along with Patrick Mahomes, Lamar Jackson and Russell Wilson, Watson is a part of the most empowered and talented group of Black men ever to play the most scrutinized and fetishized position in sports. Matt Hawthorne for ESPN

CHANGE COMES GRADUALLY. Experiences build, eventually coming together to produce a more fully formed view of the world. During the spring of 2019, Watson and Avery took a 30-day trip to Europe and Asia. In Germany, they visited Holocaust sites and learned of the strict bans on Nazi symbols. The swastika is outlawed, as are the SS bolts. Giving the Nazi salute or saying "Heil Hitler" can put the perpetrator behind bars for up to three years.

"None of that is supported or relished in Germany," Avery says. "But in America it's just different. It's like we're OK with the things that they did because it was in the past. It wasn't that long ago that people were enslaving, beating and pillaging Black people just because they were Black."

Later, they attended a military parade at Tiananmen Square in China. As it began, a lone protester dashed out of the crowd and into the middle of the marching army, screaming his message. Within seconds, he was grabbed, beaten and tossed into a van. The parade continued "like nothing happened," Avery says.

Watson and Avery talked about it later, and they kept returning to the same two words: He knew. The protester knew, in a country that does not allow dissent, exactly what was going to happen when he made the decision to run into the middle of a show of military might.

"I think it added more layers in terms of Deshaun's understanding of the sacrifices people make to make their countries better," Avery says. "Maybe it didn't click until a little bit later. Maybe it didn't click until he saw somebody put their knee on George Floyd's neck for [seven] minutes and 46 seconds."

“We got to keep pushing forward to make sure everyone knows this is what’s going on in the world and that it needs to stop -- and that it’s going to stop.”

- Deshaun WatsonPerhaps those experiences -- and the subsequent interpretation -- can be traced to Watson's decision in June to join with Hopkins to sign a petition that resulted in the removal of John C. Calhoun's name from the Clemson honors college. "I had a few classes there," Watson says, "and it felt wrong." Calhoun, the seventh vice president of the U.S., was a slave owner and a major defender of the slave-plantation system, going so far as to declare it "a positive good" that benefited slaves. While at Clemson, Watson walked in and out of that building, understanding what that name meant to students like him but inhibited by that ingrained sense of indebtedness.

"At that time, we didn't feel like we could speak out about it because we're going to be looked at differently and judged differently," Watson says. "It's like, you're at a university where the majority of the students and alumni are white, and they've given you the opportunity to get out of the hood, to get an education and go play big-time football. We probably felt some type of way, but we never really spoke about it."

Clemson was founded by Calhoun's son-in-law, Thomas Green Clemson, also a slave owner and a man described dodgily on the university's website as a man "as complex as the times in which he lived." A statue of Clemson is an iconic landmark on the campus, standing right in front of the building that no longer carries the name of Clemson's father-in-law.

"People used to tell me that when you graduate, every student takes a picture of front of the statue," Watson says. "And people used to touch it for good luck, but I never touched that statue. I know for a fact I've never seen a Black football player take a picture in front of it."

Three years ago, I took a trip to Gainesville to report a story on Watson, who at the time was in the process of building a potentially record-breaking rookie season. He had recently made headlines (unwanted headlines, since he initially asked that the story not be publicized) when he donated a $27,000 game check to two women who worked in the team cafeteria and lost their homes in Hurricane Harvey. I never wrote that story -- Watson blew out his knee in early November and missed the rest of the season -- but I met with family members and coaches and friends who uniformly spoke of a wonderful young man whose legacy is to serve as an example for every child in town.

On a Saturday morning in late October of that year, about a dozen of us met for breakfast at the Longstreet Café, the Gainesville diner that is the community meeting place. The buffet line was filled with nearly all iterations of fried food. Every Friday morning the students from Gainesville High meet there for breakfast, and one of the oft-mentioned signs of community harmony is the line of backpacks on the floor of the café on those mornings. And, it must be mentioned, one of the signs of embedded racism can be found in the café's namesake: James Longstreet, a Confederate general who died and is buried in Gainesville.

"No, I've never brought [the name] up with Deshaun, but I've thought about it many times," Avery says. "It would be hard for them to get my business. I think that's so ingrained in a lot of the culture and especially these rural towns that don't see it any other way. They don't even understand how that can be offensive. I wish there wasn't a Longstreet Café in Gainesville, Georgia. It just shouldn't be there."

This offseason, Watson became the second-highest-paid quarterback in the NFL -- behind his friend Patrick Mahomes, who sent him details of his own contract negotiations. "We're in this together," Watson says. Matt Hawthorne for ESPN

WHO KNOWS WHERE the current social justice movement will go, or what role sports will play in its unfolding. Events overlap and double back and swallow each other whole. George Floyd becomes Jacob Blake and Minneapolis becomes Kenosha and a knee to the neck becomes seven shots in the back.

Watson is new to this form of public discourse; he's a 24-year-old man trying to figure out his place in the world, and the power his voice might project. After CNN aired a story about a couple with young children being evicted from their Houston-area apartment, Watson reached out on Twitter and pledged to help them. (A GoFundMe for the family has since raised more than $200,000.) Watson spoke by phone with the father, Israel Rodriguez, and vowed to provide the family with housing, clothing and food. "Whatever they need to get back on their feet," Watson tells me this week. "He told me, 'You've got a game this week; go play the game and don't worry about me.' I love his attitude." Watson says he will contact the family on Friday -- after the Thursday season opener against the Chiefs (8:30 p.m. ET, NBC) -- to help them find a place to live.

"I'm humbled to be in a position to help change lives," Watson says, and that starts in Houston, his likely home for the next four years. This offseason, as Mahomes was finalizing a record-breaking contract that could rise above $500 million if all goes according to plan, Watson was one of the few with a backstage pass to the proceedings.

Mahomes texted him details and inspirational messages, chunks of the actual contract along with promises about how the two underdrafted quarterbacks from the 2017 draft -- Mahomes went 10th, Watson 12th -- are going to change the game. And six days before the two face each other in the first game of the NFL season, Watson signed his own monstrous contract extension: four years and $160 million, the second-largest contract in NFL history.

"He hit me up and congratulated me," Watson says. "We've been going through the process together, and we both accomplished our goals. Now it's time to go out there and compete -- that's the beauty of brotherhood."

This weekend, 10 Black quarterbacks are expected to start at the position for their teams, the most in NFL history, and perhaps it was inevitable that a social justice movement among players in the NFL would gain traction only if led by those men. The NFL announced league-wide initiatives: Players and coaches have the option to wear decals or patches honoring the victims of systemic racism, and slogans will appear in each end zone. Earlier this summer, Texans coach Bill O'Brien, partly in response to Watson's activism, vowed to kneel with his players, and every team is expected to either kneel en masse or engage in another form of unified protest (Watson said Monday that he and his teammates are still discussing their actions for the season opener). It's jarring to consider: Four years after Kaepernick began his protest, kneeling in 2020 will be seen as the socially acceptable protest, nonthreatening and comfortable. Kaepernick was a soloist; Watson is one voice in a chorus.

"It feels different," Watson says. "It feels like a change is happening. It feels like voices are getting heard."

He is no longer the guy shrinking onstage in January. His tone is no longer conciliatory and overly deferential. Enough. Watson is correct: Voices are getting heard, because voices are getting used -- some for the first time.

Styling by London Wilmot; suit by OBHG; shoes by Prada; top by Dior Homme; jacket, sweatshirt and pants by Ermenegildo Zegna XXX.