|

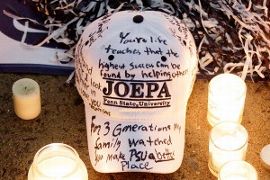

STATE COLLEGE, Pa. -- Jay Paterno parked his minivan on the side of Porter Road, looking at the solemn crowd gathered around the statue of his dad. It was Tuesday night, and a shrine had been forming near Joe's feet for days. Someone left a war medal. There were dozens of flower arrangements, 30-year-old seat cushions and a houndstooth cap. For a moment, he took in the scene: the bronze statue, the flickering tea candles, the bright lights of the football stadium kept lit in memory since Joe Paterno died.  Jay pulled a hood over his head and slipped in among the crowd. Nobody recognized him. His father didn't seem so far away here. It was comforting. He bent down to read a card: "There's a new angel in heaven." A handmade poster showed Joe walking through gates with carefully drawn wings on his back. The only sounds came from wind and sniffles, and Jay zipped his coat against the cold. He stood next to a schoolteacher from Pittsburgh who worked all day, then drove three winding hours, bringing her dog, Rufus, for company. She went to the public visitation and then came here, to say goodbye. Before driving home in the dark, she wanted a photograph in front of the statue, so she turned to the stranger on her right. "Would you mind getting a picture with the dog?" she asked, handing over her camera. "One … two … three," Jay said. She looked at the lens, and Rufus managed not to squirm too much. Then, as the candle she lit burned, she stood still. Maybe she was praying. But something else was working in her memory. A familiar voice. She looked again. "You're not … ," she asked quietly. Jay Paterno nodded. The schoolteacher from Pittsburgh collapsed in his arms.

The goodbye to Joe Paterno ends Thursday with a public memorial service. The basketball arena holds 15,261 people, and the free tickets went in seven minutes. Hotels are full. Thousands of people lined the streets for Wednesday's funeral procession. The city buses said "Paterno Proud" on their electronic marquees. Everything in State College had stopped, but, alongside the public mourning, a family was dealing with its private grief. As Jay Paterno pulled away from his house Tuesday night, a friend asked from the back seat, "How's your mother?" "Uh …," he said. "OK." He paused. "I don't know. I can't imagine. I can't imagine being married four months shy of 50 years and … ." He snapped his fingers and kept driving. It was only a few miles from his house to the Pasquerilla Spiritual Center, where his father's casket lay in the main hall, flanked at all times by a current and a former Penn State football player. Jay hadn't planned to go to the public viewing, but he found himself drawn there. He felt as if he should let people know what their support had meant in the past days. And, honestly, the busier he stayed, the less he had to deal with his new reality. "I can't pick up the phone and ask him things anymore," he said, turning toward the football stadium. There is a day of reckoning coming, maybe as soon as tomorrow. Jay knows that. He's gotten brief glimpses of the future. On Sunday night, the day his father died, a friend called and said he had to come see the students' impromptu candlelight vigil. "It's like a Frank Capra movie," his friend told him, the kids walking through the dark from campus, with no plan, just drawn to Paterno's statue as Jay is drawn to them. That was when it first hit him. His dad was really gone. Monday night, after working on his eulogy and finally crawling into bed, it hit him again. The grief came and went, an unwelcome visitor, and he pushed it away when it arrived, trying to tell jokes, rushing around to offer and reoffer friends a soda or a beer. Maybe that's why he only glanced at the stadium as he approached it, keeping his eyes on the road. There was a photo of his dad on the giant video screen. Joe Paterno stood with his arms crossed and the beginning of a grin.  "That smirk," Jay said. "I've seen that face a million times." He turned onto campus. Small groups walked through the shadows, people wearing heavy coats. They were leaving the viewing. Hundreds more waited their turn to go in. They'd been lined up all day. All the television cameras in the world couldn't sum up the past four days in State College because the poignancy wasn't in any individual act of devotion but rather in the volume and earnestness of the acts. There was also the unexpected intersection of the public and the private mourning, where that line blurred and disappeared. Sue Paterno visited the statue to show her gratitude for those gathered there. Former coach Tom Bradley walked the line outside the spiritual center and thanked mourners for coming. Of all the gifts people can give in times of sorrow, showing up might be the greatest. That was true for the family and for the fans. So these groups with their heavy coats were more than just people walking down a campus street. Everything about them, their location and body language, sent the message to Jay that they missed his father, too. It's a simple thing, but it's getting him through the week. Jay pulled up to the spiritual center, parking behind the blue hearse, near a building filled with strangers. He could postpone his own pain by helping them deal with theirs. Jay searched for the right word to describe what their presence meant. "It's sustaining," he said. "You know you're not alone."

The worship hall is a long room with high ceilings. A line ran the length of the far wall, turning so each person could have a moment alone before the casket, which was covered in white flowers. It was nearly 10 p.m., with another hour left of the public viewing. Jay stood near the exit. He wore a tie and a sweater vest. He didn't look at the casket a dozen yards away. He gripped every hand. Didn't rush anyone. Wrapped them in a bear hug at the first sign of a quivering lip, which usually ended with them crying on his shoulder. "Lean on me a little bit if you have to," he said. "He's been my hero for 45 years," one middle-aged man said. "Mine, too," Jay said. A student trainer from 1999 passed through the line. Two athletes on crutches. Jay was pleased by the diverse mix of people: old and young, men in fancy shoes and in Chevrolet racing hats, white, black, students with Indian accents, with Chinese accents. The man who installed a water pump in Jay's house offered condolences. Members of the Penn State lacrosse, softball and rugby team came. There was someone whose mother died in July. He presented a single red rose. A distinguished-looking man in a worn West Point sweater stopped. "My son is a disabled West Point grad," he said. He struggled to get out the next sentence. "Your dad was so good to him," he said finally.  People said all kinds of things. They said Joe was a great man. They said he'd be missed. They said they shared a birthday with Joe and were "so proud of that." They said they didn't know what to say. One woman touched Jay's heart with her hand. "He's always been part of my life," someone said. "He's still with you," Jay replied. The last person in line, a young man with a crew cut, passed by Jay, and, after nine hours, the viewing was finished for the day. The room cleared out. It was past 11 p.m., and the grief was private again. Jay said his goodbyes and gathered his friends to visit the statue, where he would meet a woman and her dog. Sue Paterno knelt on the steps leading from the altar to the sanctuary. One of Joe's young granddaughters, who couldn't have been more than 9, approached the casket and gave it a kiss.

After the schoolteacher recognized Jay, after their hug, she leaned down and worked frantically on Rufus' collar, her hand unsteady from the cold and the nerves. Jay looked at her, a bit confused. Finally, she loosened the Penn State bandanna around Rufus' neck and said she wanted to leave it at the shrine. Jay said he'd like it for his dog at home, and she presented him with the blue cloth. He thanked her, told her to drive safe, and slipped the bandanna into his pocket. Not much later, when he had returned home, he told the story to the friends left around his kitchen table. There was awe in his voice, and it was clear he'd brought home more than a gift for a dog, or even a story. He's brought that woman home with him, and all the people he'd met at the visitation, and even the ones he's seen on the streets of the campus and the town. He brought all of them home, and they would stay with him. Jay held an ice pack against his right hand, which was sore from hours of comforting strangers, and he began the story again, telling his wife about a schoolteacher who drove from Pittsburgh to say goodbye. Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com.

|