|

This story appears in the Oct. 3, 2011, issue of ESPN The Magazine.

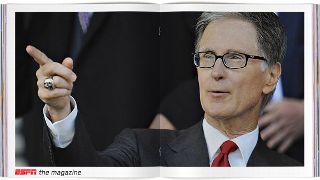

"Take nothing on its looks; take everything on evidence. There's no better rule." -- Mr. Jaggers, Pip's guardian in Great Expectations by Charles Dickens. WHERE'S DICKENS when you really need him? For the record, he passed away 141 years ago, 11 years after he wrote Great Expectations, three years after a triumphal swing through Boston and two years before the Red Stockings began their run of four straight National Association pennants. So Dickens was gone before the Boston baseball saga really began, before the emergence of the same elements that made his work so compelling: the plot twists, the comic names (Johnny Pesky, Bill Monbouquette, Jonathan Papelbon), the shroud of the fog off the fens, the rabid mob, the haunting presence of the bride-not-to-be -- he actually put Miss Havisham out of her misery well short of 86 years. Even the title itself speaks to the history of the Red Sox. He certainly would have appreciated the arrival 10 years ago of a pale, thin, mysterious benefactor who would save the day and the ballpark, not to mention the self-esteem of Red Sox Nation. Absent Dickens, we might have to rely on the Dickens of baseball writers, Peter Gammons, to describe John William Henry II. "A wonderful man," says Gammons. "A strange and wonderful man." What Henry has done in Boston since his arrival is assuredly wonderful. With the help of Tom Werner and Larry Lucchino, Theo Epstein and Tito Francona, Papelbon and Papi, he has transformed the franchise from the mom-and-pop Sawx into a team that could contend on a yearly basis with the guys from the Bronx. Henry has brought Boston not one but two World Series trophies and made Fenway the best experience in baseball, witness its 700-plus (and counting) straight sellouts.

" Henry is a whole host of contradictions. He uses dispassionate analysis in pursuit of his own passions. "

Henry loves facts -- "I don't read fiction" -- so here are some. He was an asthmatic farm boy who grew up worshipping a miner's son named Stan Musial; a philosophy major who fell under the thrall of Indian individualist Jiddu Krishnamurti; a rock musician who shaved his eyebrows to play a space alien in a rock opera; a mathematical whiz who was banned from Las Vegas blackjack tables; a commodities trader who watched soybeans grow into a beanstalk that eventually yielded ownership of some of the most storied franchises in Major League Baseball, NASCAR (Roush Fenway Racing) and the Premier League (Liverpool FC). You have to make this stuff up. But it's not just Henry's bio that makes him interesting. He's a whole host of contradictions. He uses dispassionate analysis in pursuit of his own passions. He's a serious thinker given to practical jokes, a shy fellow who counts Bill Clinton, Michael Douglas and Steven Tyler among his friends, an owner of a 164-foot yacht who will dash from the owner's box above home plate at Fenway to the first-aid room to check on a fan who's been hit by a foul ball. He may be a 62-year-old father of two girls (a 14-year-old and a 1-year-old), but he has never lost his own childlike sense of wonder. He's also the kind of person who politely declines personal interview requests, then spends hours thoughtfully responding to e-mail questions -- at 12:32 a.m. To a query about the major influences in his life, he writes, quoting mythologist Joseph Campbell, "'If you follow your bliss, you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while, waiting for you ...' That's what led me into the financial world. I started John W. Henry & Company because I enjoyed applying mathematics to markets, and it was a profound challenge that resonated within me."

"We had a good name, and worked for our profits, and did very well." --Pip In a way, Great Expectations is a business story about the changing fortunes of Pip, the orphan. So, as with Magwitch, the convict who became Pip's benefactor, you have to ask, where did John Henry get his money? Henry grew up on his father's farms in Quincy, Ill., and Forrest City, Ark., listening to his beloved Cardinals on the radio. He finally got to see them in person when he was 10 -- but only because his father was hospitalized in St. Louis with a brain tumor. "It was really heaven and hell," he told Seth Mnookin in Feeding the Monster, a 2006 book about the Red Sox. When Henry was 15, the family moved to the high desert country of Apple Valley, Calif., to help control his asthma. Henry studied philosophy at various colleges but then dropped out for music -- hence the rock opera. When his father died in 1975, Henry took on the responsibility of the family farm in Forrest City. The 1,000 acres of soybeans led him to an interest in the commodities markets. On a hunch that soybean prices were about to rise, he made a big play, and sure enough, they jumped from $7 a bushel to $13, according to Mnookin's book. He thought the price would go even higher, but before moving back to Illinois to be with a girlfriend who was having anxiety attacks, he sold his shares. Henry was fortunate because the price plummeted to $4 a bushel. That scare spurred him to devise a system that did not rely on hunches, and for the next several years he researched trading history across centuries and hemispheres. In the summer of 1980, while on vacation in Norway with his first wife, Mai, he took advantage of the lost-in-translation boredom to refine a model that would help him identify market trends early. Called "managed futures," his system was designed to strip ego and emotion out of the decision-making process by pinpointing trends and then riding them. With that system in place, he started John W. Henry & Company in 1981 out of a tiny office in Newport Beach, Calif. Soon enough, with a growing list of clients, he was opening offices in Westport, Conn., and Boca Raton, Fla. Of course, the market isn't

always predictable: On one day in 1985, he lost 10 percent of his clients' money when the dollar suddenly weakened. One of his clients, a fund named Iroquois, pulled out in favor of a rival adviser. John W. Henry rode out the plunge and went on to a great year; Iroquois, in the meantime, went bust. But it does live on in the name of Henry's yacht: My Iroquois. That in itself tells you something about the man. Henry loves games, and he doesn't like losing them. He played the APBA dice baseball game as a kid, and he has played in fantasy leagues with his employees. One of them is Matthew Driscoll, who first went to work in the Westport office in 1991. "My hours were 9:30 p.m. to 10 a.m.," says Driscoll. "I was on the overseas trading desk, and I would get these great calls from John at 2 a.m. talking about baseball, asking how the Japanese market was doing, talking about family. His mental stamina is amazing. So is his competitive nature. One year we set up a league around this auto racing simulator, and at first John wasn't doing that well because his reflexes weren't as sharp as the younger guys'. But he became so consumed by it that he ended up winning the whole thing." Fantasy sports led to the real thing in 1989, when Henry bought the West Palm Beach Tropics of the short-lived Senior Professional Baseball Association, a retiree league for nostalgic fans. Managed by Dick Williams and led by shortstop and future Rangers manager Ron Washington (73 RBIs in 72 games), the Tropics went 52-20 and ran away with the Southern Division, only to lose to the St. Petersburg Pelicans in the championship game. Henry lost some $1.4 million on the Tropics, but his company was handling billions in assets, and he did get to meet his second wife, Peggy, when she installed the computer system for the club. He also caught the bug of ownership. After he bought a 1 percent share in the Yankees for $1 million in 1991, he tried to put stakes in various MLB, NBA and NHL teams. In 1999 he became the sole owner of the distressed and dismantled Florida Marlins, buying them from Wayne Huizenga for $158 million the year after the club had gone from a World Series title to 108 losses. Henry ingratiated himself with the fans, his players and his fellow owners, but winning was never an option with the Marlins. The team was a mess, and so was the ballpark situation. As it happened, the same could be said at the time about the Boston Red Sox.

"Pause you who read this, and think for a moment of the long chain of iron or gold, of throns or flowers, that would never have bound you, but for the formation of the first link on one memorable day." --Pip Larry Lucchino remembers getting the call on Nov. 3, 2001, while he was at the Yale Bowl, watching Yale play Brown in football. It was from Henry, and he was inquiring about the Red Sox sale. Lucchino, a baseball executive who had turned around franchises in Baltimore and San Diego, was then allied with Tom Werner and Les Otten in their bid to buy the Red Sox from the Yawkey Trust. Henry, for his part, was looking to get out of Florida and had explored buying other clubs, including the Angels and A's. "Until that call," Lucchino says, "the best thing we had going for us was that we were the only group among the serious bidders who wanted to keep Fenway Park. But we needed financing, and John offered us that. Plus his mind." Werner, who made his money by producing such TV staples as The Cosby Show, had owned the Padres before Lucchino got there, but he had never met John Henry. So Henry flew out to the West Coast to meet him. "I instantly took a liking to him," Werner says. "I could see we shared the same values, one of which was the preservation of Fenway." The group still faced a formidable obstacle. Its members were viewed as outsiders, people who didn't understand Boston the way some of the other bidders did, bidders such as local parking lot baron Frank McCourt. And the bidding process turned byzantine, with shifting alliances and balking investors. But with Henry providing most of the financing and commissioner Bud Selig on their side, their bid of (gulp!) $695 million was accepted on Dec. 20, 2001. That didn't mean they were immediately accepted by Red Sox Nation. "We were told all the things we couldn't do," Lucchino says. "We couldn't add on to Fenway because it was going to sink into the ground. We couldn't change the Green Monster -- that was sacrosanct. But John encouraged us to think differently, to think for ourselves. And because we all had small-market experience, we brought a tremendous work ethic with us." And a certain play ethic as well. On one of the early days of the new regime, Henry took a photo of Lucchino sleeping in his office and posted it in the lunchroom under a note that read: NEW RED SOX CEO HARD AT WORK. Once the triumvirate of Henry, Lucchino and Werner got to work, they discovered untapped revenue streams by spending money to make money: adding seats on an almost yearly basis, buying surrounding properties to make Fenway a small city unto itself. They pulled off the neat trick of selling lots of signage without ruining the character of the ballpark, and they turned NESN, the cable network they acquired in the Red Sox sale, into a cash cow that's the envy of baseball. "You can't win in any sport without heavily concentrating on revenue generation," Henry says in an e-mail. "You have to be relentless in that regard if you are going to be able to afford the kind of players you need to compete at the highest level. There simply is no way around that." Asked to describe his management style, Henry writes, "I'm a tough manager. I question almost every assumption in what are hopefully pragmatic ways. The more you question, the more you learn and the more the person you are questioning learns ... More than anything else, management is a question of ensuring you have the right people in place and they have the resources necessary to be successful." The club Henry inherited didn't have either the right general manager (unpopular Dan Duquette) or the right manager (old-school Grady Little) in place. The Red Sox thought they had a deal with Moneyball hero Billy Beane after the 2002 season, but he famously decided to stay with the A's, so the Red Sox took a chance on Lucchino's young protege, Theo Epstein. "Early on in my tenure," Epstein says, "I made a couple of decisions in a row that backfired on us. John and I were talking on the phone, and John drew a parallel to his other business, noting that in the world of stocks, there are two ways to react in the face of poor results. Some abandon their beliefs and adopt any new approach, searching for a quick fix. Others cling even tighter to their core beliefs and ride out the storm. The former group, he said, inevitably fails, while the second group prospers in the long run. I still think of that conversation to this day in tough times." As for Little, well, he did get the Sox to the postseason in 2003. But then came Game 7 of the ALCS in Yankee Stadium, when he sent Pedro Martinez out to pitch one more inning, the eighth, with the Red Sox up 5-2. As calm and peaceful as Henry is, he can get angry. "Can we fire him right now?" he asked Lucchino. The rest, including Little, was history. To replace him, the Red Sox interviewed several candidates, including Joe Maddon, but Henry was sold on ex-Phillies manager Terry Francona, who was raised in the old school but embraced the new school. "There has been a time or two when things have been really rough," Francona says, "and he has sent me an incredibly encouraging e-mail. It's always in the middle of the night, so I know he's not sleeping either. He is a quiet gentleman who wants to win very badly. I like that!" Another key hire was pure Henry: iconoclastic statistician Bill James. His lifework has been to take some of the guesswork out of baseball decisions, the way Henry himself had taken the guesswork out of soybean trading. James actually came up with a way to determine how a player's lack of hustle had affected the team. And one of his first discoveries for the Red Sox was that a first baseman released by the Twins after the 2002 season -- David Ortiz -- had a much higher "secondary" average (which basically measures bases gained) than his batting average, i.e., he was undervalued. Ortiz, of course, was nothing short of legendary in Boston's epic 2004 postseason, when all the elements came together and the Sox came back from a 3-0 deficit to the Yankees in the ALCS and then swept the Cardinals, Henry's boyhood favorites. Werner loves to recall the plane ride back from St. Louis. "We were all riding in first class, and we have the World Series trophy cradled between us. I didn't think we could ever be happier -- until we saw the reception waiting for us at Logan Airport when we landed at 4 a.m."

" "I instantly took a liking to him," Werner says. "We shared the same values, one of which was the preservation of Fenway." "

But the times haven't always been that good. Patriots owner Bob Kraft had warned Henry about the pressure of defending the title, and at the end of the 2005 season, a frustrated Epstein walked out -- in a gorilla suit to disguise himself -- over his simmering, almost biblical feud with Lucchino. At an emotional news conference that November, Henry blamed himself for Epstein's resignation, saying, "Maybe I'm not fit to be principal owner of the Boston Red Sox." But then he began a reconciliation process that smoothed over the tensions and ultimately resulted in the 2007 World Series trophy. In fact, Henry feels that his proudest accomplishment is that title. He writes: "Winning in 2004 was heartrending -- deeply emotional -- because Sox fans had waited so long ... but ... the second championship proved that we had the right people in place and the right philosophy." Not everybody applauds the Red Sox's success, however. Some people see a sort of hypocrisy in the way former small-market executives complain about the unfairness of revenue sharing. Under MLB's current system, all teams kick in 31 percent of their local revenues to a pot that is equally distributed to all 30 teams, meaning the large-market teams contribute more. Plus, revenues from sources such as national broadcast contracts are disproportionately allocated, so lower-revenue teams get a bigger piece of the pie. Henry has criticized that system and has been fined $500,000 by Selig for his critiques. "Listen, I have nothing but admiration for what the Red Sox have done," says Stu Sternberg, the Rays' principal owner. "But when they complain about sharing their revenues, you have to ask, do they care more about themselves or about the good of the game?" Ah, but John Henry is a capitalist, after all. Describing the partnership between the Fenway Sports Group and Roush Racing, he writes, "One reason investing in Roush appealed to Fenway was our frustration over baseball's economic system. We began to look for revenues outside of baseball." As for purchasing Liverpool FC, a franchise with uncanny parallels to the Red Sox, he writes, "We've driven revenues as far as baseball will allow, and here was an opportunity to compete globally in a league without borders."

"Suffering has been stronger than all other teaching, and has taught me to understand what your heart used to be. I have been bent and broken, but -- I hope -- into a better shape." --Estella Goodness knows, Red Sox fans have suffered over the years. You might think the two titles would've relaxed them, but they're even more intent on winning. And that's fine with Henry. Here's how he answered the e-mail query "Sox fans can be so demanding that they can seem ungrateful. How closely do you listen to them?"

" Sox fans stew because, even after 10 years, they don't really know John Henry. "

"I honestly haven't met ungrateful Sox fans. The most common thing said to me is 'Thank you.' They're grateful that we were able to save Fenway ... They're grateful that we have put solid teams together every year ... But they give us that ability." Even though Henry is still considered one of the "new owners," the Fenway faithful show their appreciation by worrying about him. They fret that his newfound obsession with Liverpool FC will distract him. They're concerned that his beautiful 32-year-old new wife, Linda Pizzuti, will somehow upset the chemistry that has proved so successful in turning the Red Sox into a perennial powerhouse. They stew because, even after 10 years, they don't really know John Henry. Which is sort of the idea: The Red Sox zealously guard his space and time. That's why most of his interviews are conducted in the ether of cyberspace. His multiminded devotion to all his interests inspires his colleagues, which is why the Red Sox lead the majors in workaholics. His decency is also noted and appreciated. Bill James describes a little thing Henry does that means a lot to him: "I use a different e-mail address than the normal Red Sox account, which irritates the hell out of some higher-ups. But John remembers. Once in a great while, he'll forget and send something to my Red Sox account, and I won't answer it, but then he'll apologize in the next e-mail for using the wrong e-mail. Think about it." Dispassion, check. Passion, check. Both have been instrumental in Henry's success as a businessman. But so has compassion. Perhaps the best way to think of the Red Sox is as a symphony orchestra, with Henry as the conductor of the talented, occasionally fractious sections. (That was Manny Ramirez on the bass drum.) He knows the score for every instrument; he wields the baton with energy and verve; and he makes sure that everyone takes a bow.

"I was very glad afterwards to have had the interview." --Pip, in the original ending of Great Expectations. The verbal testimony of others, together with the bounteous words of Henry himself, should be enough to give you a sense of the man. But feeling a bit like a Red Sox fan who calls in to complain about Carl Crawford, I wasn't quite satisfied. During the second game of the recent three-game Yankees series at Fenway, Henry and Werner were making an appearance in the NESN booth on behalf of the Jimmy Fund, so I waited in ambush to introduce myself. "Come by tomorrow night," he said. And that was how I found myself in his stately box with his kindly attendant, looking down on Henry and Werner in the field box alongside the Red Sox dugout, reliving old times with 2004 folk hero Kevin Millar. From Lucchino's box next door, visitor Phil Mickelson looked over at me, wondering what I was doing there. (What I was doing was calculating how much money a year the Red Sox get from the 269 seats atop the Green Monster: $200 for tickets and concessions x 269 seats x 81 games = $4,357,800.) For a few lonely minutes there, I thought Henry might not come up at all, but at the end of the third inning, he made his way upstairs. When he arrived, he graciously invited me to sit beside him in the front row. As a conversation starter, I mentioned my own fondness for the Senior League. "I was so intimidated by Dick Williams," said Henry of the late Hall of Fame manager. "At one point I called him from Arizona all excited to tell him I could get Graig Nettles. All he said was, 'I don't want Graig Nettles.' So I got him Toby Harrah instead. We had Dave Kingman, Mickey Rivers, Rollie Fingers, Al Hrabosky. Great times." Henry tracked a foul ball carefully to make sure it didn't hit any fans, then talked about the injuries he had seen over the years from balls hit into the stands. He said he thinks one of the best baseball stories ever is Dustin Pedroia -- "our 5'8" cleanup hitter" -- and, as if on cue, Pedroia hit a two-run homer off Yankees righthander A.J. Burnett to give the Sox a 2-1 lead and bring Henry to his feet in appreciation. In between rounds of visitors, we chatted about the new "Temperature" metric James had just concocted (at Henry's suggestion) to measure how hot or cold a player really is. The conversations were brief, snippets really, but dizzying and delightful. A mention of the new Stan Musial book led to an anecdote about Joe DiMaggio, which led to ... "Here's a story. When I was owner of the Marlins, I agreed to participate in an old-timers game to benefit the Joe DiMaggio Children's Hospital. Al Hrabosky [a lefty known as the Mad Hungarian for good reason] comes up to me before the inning I'm supposed to bat and tells me he's going to throw me two strikes and then a ball behind my back, at which point he wants me to charge the mound like I'm angry at him. So spindly me gets up, and part of me is thinking, I could get killed, and part of me is thinking, Wait, there's a runner on second and we're behind by one run, so maybe I should try to get a hit. "Well, I survive the first two pitches, and sure enough, he throws the ball behind me. I charge the mound, but the grass is wet, and just as I reach the mound, my feet slip out from under me and I slide feetfirst between Hrabosky's legs. He looks down at me and asks, 'Are you all right?' I was fine ... except for my dignity." I parted after the sixth inning, just before the Yankees took a 4-2 lead. I watched the bottom of the ninth from the top of Fenway, along the rightfield line. The Red Sox loaded the bases against Mariano Rivera with two outs, bringing AL batting leader Adrian Gonzalez to the plate. But I wasn't looking at either one of them. I was looking down at the thin man sitting alone in his box above the field, riding on every pitch. When

Gonzalez struck out looking, I could feel Henry's anguish -- even from a distance. The wealth, the trophies, the years all melted away, and he looked like one of the thousands of disappointed kids in Fenway. I don't know how else to describe it. Maybe Dickens could. "Now I return to this young fellow. And the communication I have got to make is, that he has great expectations." --Mr. Jaggers Steve Wulf is a senior writer for ESPN The Magazine. Follow The Mag on Twitter: @ESPNMag.

|