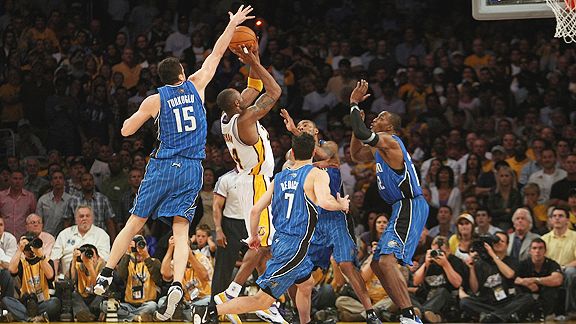

Stephen Dunn/Getty Images Sport

Stephen Dunn/Getty Images SportAt the end of Game 2 of the 2009 Finals, the Magic knew who to guard, and got the block.

Ask pundits. Ask general managers. Ask players. Ask almost anybody.

Who would you like to have take the last shot with the game on the line?

Kobe Bryant wins by a country mile. Every time. (In a general-manager poll this season, he earned 79 percent of the vote, his ninth consecutive blowout.)

There is not really any other serious candidate.

Ask me, though (as Ryen Russillo did last week and Mike Trudell the other day), and I'll tell you I don't know who's the best, but with all due respect to Bryant's amazing abilities scoring the ball, there's zero chance he's the king of crunch time.

The sin of predictability

Bryant makes crunch-time defense easy for opponents by shooting just about every time he touches the ball (over a five-year period, he mustered 56 clutch shots, to go with one assist).

Fans of his raw machismo howl that such criticism misses the point, but the point is that when Bryant gets the ball in crunch time, it's a virtual certainty that he'll shoot it, and it's better than 2-1 odds that he'll miss.

In 1997, he famously air-balled two shots that could have beat the Jazz; instead, the Jazz won the series. In 1999, he whiffed on a 3-pointer at the buzzer that would have tied Game 2 against the Spurs. In Game 4 against the Kings in 2002, he missed a 2-pointer that would have tied the game (before the ball was tipped out to Robert Horry for the winning 3). In Game 7 of that same series, Bryant missed a tip that would have won the game in regulation. In Game 3 against the Timberwolves in 2003, he missed two key shots in the last seconds of overtime, and the Lakers lost.

I'll spare you the entire list, but it's long. In the final 24 seconds of playoff games, Bryant has racked up almost as many air balls as makes, making just below 30 percent of game-tying or go-ahead shots. He hasn't hit such a shot in a playoff game, in fact, since 2008, including key misses in the closing moments against the Jazz and Magic in 2009, and the Thunder and Suns last spring. He made one of his four shots in the fourth quarter of Game 7 of last year's Finals.

No matter how you define crunch time -- from the last five minutes of the fourth quarter or overtime to the last 24 seconds -- and no matter how you define production -- field goal percentage, offensive efficiency, David Berri's Wins Produced, the results tell the same story: Bryant is about as likely to hit the big shot as any player.

ESPN Stats & Information's Alok Pattani dug through 15 years of NBA data (see table below) -- Bryant's entire career, regular season and playoffs -- and found that Bryant has attempted 115 shots in the final 24 seconds of a game in which the Lakers were tied or trailed by two or fewer points. He connected on 36, and missed 79 times.

One shot for all the cookies. And the NBA is nearly unanimous that this is the guy to take it, even though he has more than twice as many misses as makes?

His crunch-time production is slightly higher in the first half of this season, but still certainly not the best in the league. And analyzing any large number of games, one year, five years or 15 years, and defining crunch time a number of different ways, shows the same pattern. (There are many ways this has been sliced.)

Bryant shoots more than most, passes less and racks up misses at an all-time rate. There is no measure, other than YouTube highlights and folklore, by which he's the best scorer in crunch time.

The un-clutch Lakers

One of the key arguments in his favor is that he draws double-teams, which allows other Lakers to score. But that doesn't seem to happen much. Over Bryant's 15-year career, the Lakers have had the NBA's best offense, and second-best won-loss record. No other team can match their mighty 109 points per 100 possessions over the entire period.

You'd expect Los Angeles to also have one of the league's best offenses in crunch time, right? Especially with the ball in the hands of the player most suited to those moments.

That's not what happens, though. In the final 24 seconds of close games the Lakers offense regresses horribly, managing just 82 points per 100 possessions. And it's not a simple case of every team having a hard time scoring in crunch time. Over Bryant's career, 11 teams have had better crunch-time offenses, led by the Hornets with a shocking 107 points per 100 possessions in crunch time, a huge credit to Chris Paul.

The Lakers are not among the league leaders in crunch-time offense -- instead, they're just about average, scoring 82.35 points per 100 possessions in a league that averages 80.03. They are, however, among the league leaders in how much worse their offense declines in crunch time.

When Bryant is on the floor in crunch time, Bryant's Lakers are actually outscored by their opponents.

A great offensive team performing at average levels, with a star setting records for number of shots attempted. Teammates left wide open. Evidence, even, that Bryant's play puts his team into nailbiters that needn't be so close.

That, my friends, is a ball hog.

The makes

Nobody playing today has a crunch-time résumé with half the excitement, or sheer bulk, of Bryant's: A banked 3 against Miami in 2009. Two ridiculous plays in Game 4 in that 2006 playoff series against the Suns. Making the Celtics' great defense look meaningless. Those four shots would make a career for most All-Stars. They are a mere eighth of Bryant's best moments.

Respect the brute force of numbers. If you want to see someone who has proved he can hit big buckets, nobody can rival his collected works. That speaks to his preparation, his dedication, the trust his teammates have in him, and more subtle things like how his training regimen has kept him healthy and productive for such a long time.

At all times he's cool as hell. At all times he's polished, fearless, ruthless even. Most of the time he's double-teamed. The shots are impossibly difficult. It's intimidating. He looks like a robot of crunch-time destruction, if robots could jump really high, shoot really well and scowl really hard.

Nobody can match that. So we live in a world in which Bryant has been appointed king of all crunch time, and it's not hard to see why.

And well worth noting is that over that period he has clearly been one of the best players in the world, period, leading a team that has won five championships and has the potential to win more.

Bryant's absolutely the best in the world at the game of winning the hearts and minds of crunch time. A lot goes into it: creating shots against any defense, staying calm, ignoring fear and more. It's about who most has the rest of the league by the throat. In that game, it's cowardly to pass the ball, and misses are merely the cost of doing business. In that game, degree of difficulty counts.

That game, though, is not basketball.

In basketball, entrusting the ball to the open teammate really does benefit the team. Remember when Jordan passed to a wide-open Bill Wennington in the lane? Or to Steve Kerr or John Paxson in the Finals?

Can all those players, GMs and Phil Jackson be wrong?

TrueHoop reader Terence speaks for many when he writes:

Correct me if I am wrong but I believe in most recent GM and player polls Kobe ranked number one when asked who the best clutch player was? What does this mean? The majority of the GMs in the NBA are wrong? The people that get trusted by very powerful and wealthy owners to run their teams are completely out in left field? The players that go head-to-head with Kobe Bryant on a nightly basis are just misinformed and are not qualified to answer this question? Phil Jackson, arguably the greatest coach in NBA history, trusts Kobe enough to give him that same clutch shot every single time, despite the fact that Kobe "shoots way too much," and has a "judgment problem?" That coach Jackson must be one terrible coach, he's very lucky to win those 11 titles.

It's not just players and GMs, it's almost everybody. What we see with our eyes and feel in our hearts is impossible to ignore, even when it's misleading.

With the game on the line

Trailing by one or two points, or tied, in the final 24 seconds of regular-season and playoff games since 1996-97, with a minimum of 30 shots. From Alok Pattani of ESPN Stats & Information.

Yet we get things wrong all the time anyway, for the simple reason that a lot more happens in the NBA than anybody can catalog in any objective way.

In that same GM survey, for instance, John Wall was a heavy favorite to beat Blake Griffin for rookie of the year. Kevin Durant was a slam dunk to win this year's MVP.

In that player poll, Chauncey Billups got the second-most votes as the preferred go-to crunch-time scorer. Billups is 3-of-27 with the game on the line over the past five seasons. Dead last in the NBA among those who have attempted at least 15 shots.

None of that means anyone is dumb. Instead, it means that reputation is a huge factor, and it's beyond anyone to remember and catalog 7,000 or so shots in your head.

And as for Jackson, he wants the same kind of hit-the-open-man team play every coach wants. We know this because back when he was free to speak frankly on the topic, he could not have been more clear.

"I sometimes think Kobe is so addicted to being in control that he would rather shoot the ball when guarded, or even double-teamed, than dish it to an open teammate," Jackson wrote in his 2004 book "The Last Season." "He is saying to himself: how can he trust anyone else? Well, he should learn to trust ..."

Jackson published that book in the interlude when he was not coaching the Lakers. That he doesn't talk that way is hardly bizarre -- it's admirable for a coach to keep his criticism of a colleague "in the family."

However, don't confuse Bryant's domination of the ball with Jackson's endorsement of the plan. In the same book, Jackson tells of his annoyance at Bryant's ball-hogging in crunch time. In one instance, he describes drawing up a play with multiple options, in crunch time of a 2004 playoff series against Houston. Bryant destroyed all the options; instead of setting a baseline screen for Shaquille O'Neal he ran straight to the ball. "With the twenty-four-second clock winding down," writes Jackson, "Kobe forced a long jumper, a horrible shot in the game's most critical possession. The ball did not reach the rim..."

Jackson also tells of marching, more than once, into Mitch Kupchak's office to demand that the Lakers trade Bryant. He writes things like:

"Kobe tends to hold on to the ball longer than necessary causing the offense to stagnate."

"He won't listen to anyone. I've had it with this kid."

"As usual, Kobe seemed intent on taking over."

More recently, Jackson's long-time assistant Kurt Rambis, when he still worked for the Lakers, was clear that the coaching staff preferred the team run their ruthlessly efficient triangle, with its passing and cutting, "at all times."

I see lots of evidence that Bryant dominates Lakers possessions in crunch time. But I see no evidence that it's part of Jackson's plan.

Should stats even be part of this conversation?

Yes.

But not because stats are better. But because this is a tricky -- and at least in terms of sports, important -- question. We should answer this with the best evidence we can get our hands on. In my mind, the final analysis would come from video, which captures the full complexity of the game. But that video should be of good and bad plays. And that video should consider many candidates, including Chris Paul, Carmelo Anthony, and the like -- not just the assumed king.

Remember when SUVs first came into existence? People went crazy for them. They were, it turned out, what a huge percentage of drivers felt they had been waiting for.

Malcolm Gladwell explains more than anything people liked how these big strong trucks, riding up high, slathered in airbags, made everybody feel safe. You go out there, on those crowded, scary roads, and very little can hurt you. Everyone just knew that. The SUV matched a picture in our brains: This is how a safe automobile feels.

Only it was a crock. There were real reasons, many having to do with design, why SUVs were actually surprisingly unsafe. A minivan, for instance, at the time of Gladwell's writing, was far safer. Gladwell cites safety statistics compiled by Tom Wenzel, a scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Marc Ross, a physicist at the University of Michigan, which found, essentially, that little nimble cars with good visibility -- the precise cars people were abandoning for SUVs -- were safer still.

How did we learn that? With a commonsense look at some stats, specifically by comparing the number of fatalities to the number of cars of a certain model on the road. A safe car is one you don't die in, right? That's useful.

Similarly, Bryant looks like a great crunch-time scorer. He has the right skills, the right demeanor, the right highlights, the right jewelry. But as it turns out, Bryant's clutch like an SUV is safe.

There are a lot of misleading things in this world.

And let's be clear: The numbers that doom Bryant's campaign as the king of crunch time are not really statistics. They're not formulas, or algorithms. They're really just counting -- both makes and misses for the player and the team.

If you're asking me to pick one guy to make a shot with the game on the line, there's nothing complex about peeking at the record to see how well he has done that job in the past. Every number in that chart is a real moment of NBA basketball, with ten players on the court, and Bryant in a Lakers uniform, rising, firing, and -- most of the time -- missing. These things really happened, and as much as you might want to ignore opinion, or theory, there's no real reason to ignore 79 misses, broken plays, a shocking lack of passing, a coaching staff eager for more team play, and an elite team that gets below-par results with the game on the line.

As long as your mind is open to all that, it has to be closed to the idea that Kobe Bryant is the king of crunch time.