OTL: Dear Nate

EDMOND, Okla. -- Something keeps calling Zane Fleming to the back bedroom, 10 years later. It's not a voice he hears; it's a throb in his temples, an outright ache to walk back there. Whenever he enters the room, he takes a whiff of his son's cologne, lies on his son's bed, closes his eyes and relives a day in the life of Nate Fleming.

Sometimes, he'll find himself in a packed high school gym, surrounded by homemade posters that read "Nate the Great." Sometimes he'll find himself standing by a high school desk, watching Nate sail through a calculus exam. But a lot of times he'll find himself remembering 10-month-old Nate, the most precocious baby he ever met.

He can picture it so clearly. Every night, after being placed in his crib, Little Nate would hop right out and curl into bed with his mother and father. If they told him no, Nate would cry, and Zane and Ann would cave in and let him stay. Zane had been told by friends that this was a bad precedent to set, that toddlers need to learn to separate from their parents at some point. So one night, he let Little Nate stay up until about 10 p.m., got him good and tired and laid him down in his crib. And in case the kid climbed out, Zane locked the master bedroom door.

Watch the story of the Oklahoma State plane crash, Wednesday at 6 p.m. ET on ESPNU. Oklahoma State hosts Texas at 7:30 p.m. ET on ESPN and ESPNHD.

The next morning, he woke up, thinking, wow, it worked. Then he looked over at his door and noticed a tiny hand underneath. Nate had again escaped the crib and fallen asleep trying to reach through the bottom of the door. All Zane could see was five baby fingers. God, he felt awful. So that's the memory that keeps flooding back to him, that's the one that still makes him break down, even now.

Because he'd do anything to have one more night with Nate.

Nate's story

Tom Friend tells the story of Nate Fleming, one of two Oklahoma State players killed in a plane crash that took 10 lives in 2001.

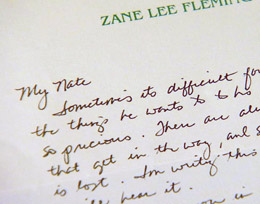

Nov. 23, 1993

My Nate,

Sometimes it's difficult for a dad to say the things he wants to say to his son who is so precious. There are always distractions that get in the way, and so part of the message is lost. I'm writing this down so I know you'll hear it. You may and you do look a lot like me, but you were made in God's image. As a child, you were perfect in every way. Truthful, sweet, optimistic, loving and ever-trusting. As a young man, He gives you the path that you choose. Humans can't give that choice. Not even daddy's. You may choose the wrong path. A lot of us do. Making the wrong choice is not forever. It seems like it is. If you choose to be jealous, hateful or discontented, then you must suffer the pain that comes with that choice. Your life will be miserable, filled with anxiety about who you really are. You will be sad trying to be as good or as smart or as rich as someone else. You might even choose to be a middle-of the-roader, someone who on the surface looks and acts confident. He might say the right things because he knows he should. All the while, he really doesn't feel good about himself and who he really is. The real truth is that there is no gray area to live your life. It's either black or white. Truth or lie. Honest or dishonest. The one who really gets fooled is you. I hope you'll choose the right path.

You have so many gifts, My Nate. Be happy with who you are. Remember, the game is won not on game-day, but in the work and preparation that leads up to game-day. Nothing can ever take away my love for you. My love and hopes for you are without end.

All my love,

Nate the boy

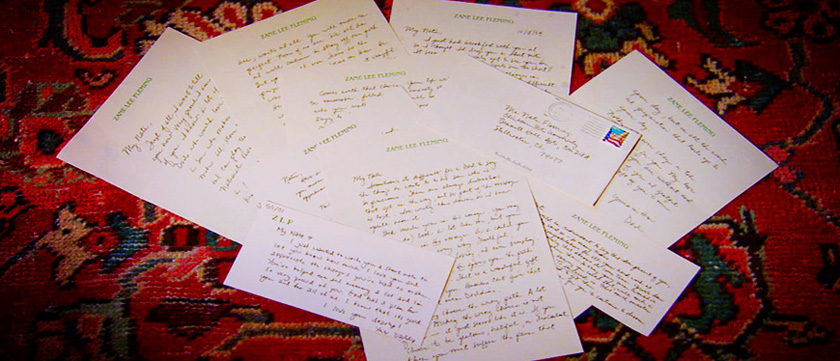

Zane Fleming began leaving notes for his son when the boy was 12. He'd write them late at night, after a long day of work, while Nate was asleep in that back bedroom. He considered them "love letters," and he'd leave them in Nate's backpack or inside the kid's tennis shoes. The idea was to leave nothing unsaid. Who knows why? It just came to him one day.

Zane wasn't sure whether Nate kept the letters or even read them. But presumably he did, because Nate had to be the most conscientious boy in the sixth grade. He was the kind of kid who wouldn't practice just his favorite sports -- basketball and tennis -- but also his handwriting. He considered his penmanship sloppy, so he'd spend hours neatly copying sentences out of a book. By high school, his cursive was a work of art. But that was Nate; he was never going to be a middle-of-the-roader.

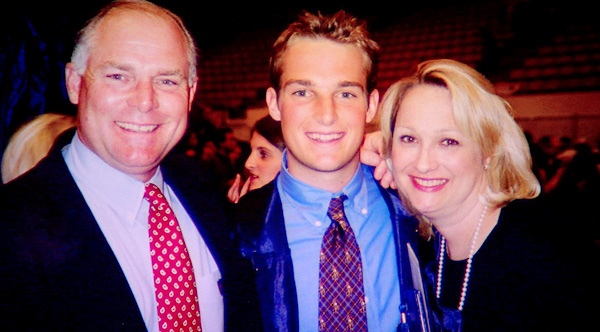

His sister Drue, 14 months older, gave him the nickname, Goody. In other words, he was too good to be true. He was a nationally ranked junior tennis player, the starting point guard at Edmond North High School and a straight-A student. He literally brought apples to his high school teachers, and no one called him a phony. Because they knew him. Because they'd seen him with Richie.

Richie Lumpkin was a wheelchair-bound student at the high school who'd been stricken with multiple sclerosis at a young age. Richie wanted nothing more than to be around the basketball team. All the players embraced Richie, but Nate, in particular, urged Richie to be a student manager, even if he couldn't do much but sit on the sideline. The players would wheel Richie in and out of the gym, in and out of the locker room, and it was usually Nate doing the pushing. Richie's mother told Zane and Ann, "I don't know how to repay Nate." But Nate said it was nothing.

On the court, the basketball team depended on Nate's every move. Coach Garrette Mantle, nephew of baseball great Mickey Mantle, would never take Nate out of a tense game because Nate was the team's head and heartbeat. Nate would calm players down, get teammates the ball in the right spots, slap the floor with his palms before playing defense. If he needed to score, he'd score, but he seemed more enthralled by other people's successes. If he wasn't dribbling, passing or shooting, he was clapping.

Perhaps his biggest influence was during practices. Nate was unafraid to chastise teammates who loafed, and he refused to do anything at half-speed. When he twisted his ankle before the state tournament his senior year and had to temporarily sit out, the team's practices disintegrated. That's when everyone knew they were riding Nate's coattails.

The only thing the kid didn't have was height or speed -- a slight problem -- which is why no Division I schools were banging on the 5-foot-11 guard's door. He dreamed about walking on at Duke or Princeton, but even though he was his school's valedictorian, both schools wait-listed him. Oklahoma State and Oklahoma (his mom and dad's alma mater) had written him cursory recruiting letters, but he'd need to walk on at both places, as well. The only firm offer was from Division III Washington and Lee, which is what Nate was mulling over during Christmas of 1998.

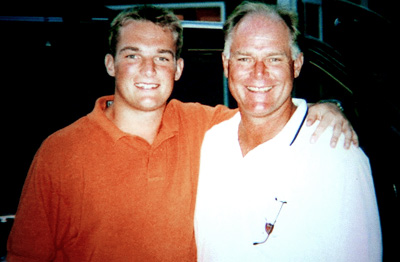

That holiday week, the family got a visit from Texas from Ann's sister Marilyn, whose husband, Ed Keller, was a prominent Oklahoma State alumnus. And they brought along their son, Kyle Keller, who just so happened to be an up-and-coming young basketball coach.

Kyle was 12 years older than Nate, and completely admired the kid. But Nate was such a whiz kid, Kyle thought it was almost his duty to bust his chops. He'd ask Nate, "You starting yet?" or "You score any points?" It was just Kyle's way of treating Nate like one of the boys, and Nate genuinely adored the byplay between them. For years, whenever Kyle visited the Flemings, or vice versa, Nate would rush up to him and want to hear coaching war stories. And at Christmas of '98, Nate wanted to talk about recruiting.

Kyle, by that time, was a successful head coach at Tyler Junior College in Texas and, as badly as he wanted to recruit Nate, he knew Nate needed to be at a four-year school that would challenge him academically. He told him that Eddie Sutton, the head coach at Kyle's alma mater, Oklahoma State, wanted walk-ons who would practice 100 miles an hour and challenge the starters. And he said Oklahoma's Kelvin Sampson probably did, too.

Still, in the spring of 1999, Kyle decided to continue recruiting Nate to Tyler Junior College. But then Kyle called the Flemings with news: He'd been hired by Sutton to be an assistant at Oklahoma State. Now, he was recruiting Nate for a Big 12 school. Now Nate was intrigued. So Kyle arranged a meeting between Nate and Sutton in Stillwater.

The gruff coach asked the kid whether he would D-up, and Nate assured him, "Yes, sir." Nate was a freebie for Sutton because, as a valedictorian, he already had an academic scholarship to the school if he wanted it. So the coach offered him the chance to walk on, and Nate left his office grinning.

Kyle was the first one to greet him. He slapped him on the back.

Oct. 18, 1999

My Nate,

I just had breakfast with you and so I thought I'd drop you a short note. Seems like we only get to see you for a little while. The visits are too short. You will have many challenges in your life. Some will be difficult and others will be just getting through that day. You've accomplished a great deal in your short life, so you already know what it takes to succeed. Not too many young men have the opportunities that you have. How you handle these opportunities is up to you. Be confident and almost cocky with your basketball. You are great and your ability and character got you where you are today. Remember: No one can make you feel inferior without your permission. Don't give into that. This will be a great year for you. Enjoy it. Seize each day. Relish in it. But don't lose your focus. You might be surprised at the opportunity that will knock on your door. You've done the work. Relax and play.

I love you dearly,

The minute the Oklahoma State seniors took a look at Nate, there was consensus: The word one of them used to describe him was "dorky."

He was barely 19, and in the same locker room as Desmond Mason and Doug Gottlieb, two of the Big 12's premier players who already had traveled the world. Nate would've been happy just to travel to Ames, Iowa, and the older players immediately grasped his naivete. They knew that his family lived next to the Oak Tree National golf course and that his sisters, Sarah and Drue, were blond and beautiful. They figured him to be a spoiled rich kid -- until Sutton rolled out the basketballs.

From the first whistle, Nate wasn't afraid to body up to Gottlieb, Mason or anyone else. As Zane had suggested, no one was going to make him feel inferior, plus the kid wanted to make Kyle and Sutton proud for taking a flier on him. No worry there -- Sutton was thrilled. Nate treated every practice like the Super Bowl; off the court, his study habits matched his on-court intensity, which Sutton hoped would rub off on all the young players. In fact, Sutton placed Nate in a Saturday morning history class for the sole purpose of helping teammates Andre Williams, Daniel Lawson and Jason Keep stay eligible. On the day of an early OSU football game, the three others skipped the class to go to the stadium; only Nate showed up. He'd never skipped anything in his life. When Sutton found out what happened, he made the other three run sprints. Nate asked to run with them.

Sutton was so thoroughly impressed that he redshirted the kid, thinking maybe Nate could help him win a game someday. But all Nate wanted, at the time, was to travel with the team, to board an Oklahoma State airplane and live the life of a big-time college athlete. He was heartened by the fact that Sutton let every walk-on take one nonconference road trip each season -- a chance to get out of Big 12 country. The trip he chose was to New Orleans for a game against LSU.

Bourbon Street. This, Nate had to see. But a few days before the flight, Nate caught a hard elbow in the nose from his friend, Fredrik Jonzen, a 6-foot-10 forward. His nose was broken; Nate's blood was everywhere. The first person who rushed in to help was Kyle Keller.

At the time, few realized Kyle was his cousin, and Nate preferred it that way. He reiterated that to Kyle, as well. He didn't want any hint of favoritism. But behind the scenes, Kyle was fielding phone calls from Zane and Ann, asking whether Nate was eating right, getting his rest and going to class. "I felt like his guardian, his caretaker," Kyle says. "And Nate could give you that because he was wide-eyed, didn't know anything, everything is new to him. And now multiply that by 10, because, gosh dang, his mom is calling me every day. I felt like I was raising a child beside the other 15 cats we had on the team."

The broken nose only enforced that. Kyle felt wildly responsible for him and had to be the one to tell him he couldn't make the New Orleans trip. "He said, 'Hey Kyle, you think I'll still get to travel tomorrow?'" Kyle remembers. "Forget the fact that his nose was over by his ear or how many teeth were falling down his throat or how much blood was on his practice uniform. He wanted to know if he could travel or not. And the answer was no."

But Oklahoma State's run in the NCAA tournament, in March 2000, made up for the missed trip. The Cowboys won their first two games in Buffalo with Nate on the bench, and before moving on to Syracuse for the Sweet 16, the team took a bus to Niagara Falls. Nate wanted to pinch himself, and the rest of the team got a rush out of how wound up he was. He had brought along two feather pillows from home, with bright red pillow cases, and the guys ribbed him about it. Nate was an easy target. Some of the players had never tried Canadian beer before, so they naturally made Nate their test taster. He was happy to comply; he would've driven the bus if they had asked him.

The Cowboys eventually beat Seton Hall to advance to the Elite Eight, and now they were on the big stage, one win from the Final Four. Gottlieb began teasing Nate that, if they won, there'd be 40,000 people at their Final Four practices, and that he'd better be able to at least touch the backboard on layups or they wouldn't let him out there. Nate had always played hard, but after that comment, he was on fire.

The day before their game against Florida, the Cowboys' starters were edgy. Sutton kicked Mason out of practice for an indiscretion, and then stuck Nate on Gottlieb, who was dealing with a sore shoulder. The last thing Gottlieb needed was some gnat in his face, but Nate was going 150 miles an hour on a day the rest of the team just wanted to jog. On one play, Nate fouled Gottlieb hard on his bum shoulder, and the two squared off. Little Nate in a fight? Sutton kicked Gottlieb out of practice, too.

On the team bus, Nate apologized to Gottlieb, took all the heat for the scrap. And the next day, no one cheered louder than Nate. Still, Oklahoma State lost to Mike Miller's Gators.

When the team returned to Stillwater, Nate wrote something on a notebook and slipped it inside a drawer. It had something to do with his hopes and dreams for the future. But he didn't mention the note to anyone. Not to Zane or Kyle. Not to a soul.

Dec. 25, 2000

My Nate,

I don't know why, but God blessed me with a perfect son. I wouldn't change one thing about you. Congratulations on all your accomplishments, but especially for showing the courage to dream big dreams and then go after them with fervor. Don't ever give that up. I'm so proud of you and I love you so very much. Merry Christmas. You are one of my angels.

When the 2000-01 season tipped off, against visiting University of Missouri-Kansas City, the coaches called for a team huddle. Sutton urged the starters to play with abandon. But before they took the floor, Nate, of all people, burrowed in front of them to make a personal demand.

"Get me a ticket,'' he said.

In layman's terms, he was telling the guys to blow the other team out so he could get in the game. The players embraced it, because, if anyone deserved to get minutes, it was their Nate, the practice Hall of Famer.

Some of them called him "Rudy." Privately, Nate seethed over that. He was not a mascot; he considered himself a baller who only needed a chance. And as the Cowboys built up a large lead against UMKC, he kept peeking over at Sutton.With one minute left, the coach pointed at Nate to go in. The bench erupted. Nate quickly found himself with the ball and was fouled. When he made one of two free throws, the guys on the bench stomped their feet again. The Oklahoma State crowd sensed the team's joy, and, voila, Nate became a fan favorite.

Before the next game, against North Texas, Nate again asked his teammates to get him a ticket. Late in the game, with the Cowboys winning big, the crowd began to chant, "Nate! Nate!" Sutton was amused. He tantalized the fans by waiting a little longer. Then, when he finally inserted Nate, the spectators chanted, "Eddie! Eddie!"

Now, Nate was considered the team's victory cigar, and the next goal was to get him to score a bucket from the field. The players and fans were in Nate's corner because he was a bundle of energy on the bench. During timeouts, he'd tell the starters, "You're not playing well … pick it up … run out on the 3-point shots … I've got half the talent you do, and you're playing like crap."

He couldn't sit in one place. He'd begin the game on the end of the bench, then move up next to Kyle at the front of the bench. Coaches had to tell him to hush during timeouts. During the action, the players on the sideline would be sitting on their hands and Nate would be the lone player standing, sometimes leaping. So, it became a teamwide obsession to reward him with shots in a game. Then, on Dec. 22, 2000, late in a blowout against Lamar, Nate finally had the ball with an open lane to the basket.

He dropped in a driving layup and sprinted back on defense as if it were a tie game. According to Kyle, Nate looked "pissed off." He didn't understand all the commotion. He didn't get why all the starters on the bench were dancing and why the crowd at Gallagher-Iba Arena was howling. He didn't get why Kyle considered it one of the greatest moments of his life or why Zane was near tears. This was going to be the first of many baskets. He was supposed to score. Didn't they know he wasn't a middle-of-the-roader?

On New Year's Eve, Sutton held a grueling, late-night practice -- and scheduled another one for early New Year's Day -- just so his players wouldn't be tempted to go out and get into mischief. Nate hustled during practice as usual, then drove the 45 minutes back to Edmond. When he arrived, all of his high school friends were already out for the evening, as were his sisters, so he decided to stay in with his mom. Ann cooked him a hearty midnight breakfast of bacon, eggs and pancakes. With Zane asleep, it was just the two of them. Nate brought out his guitar and played some of the songs he'd been working on. It was 2 a.m. She remembers it being a "magical" night. Then he looked at her and said, "Mom, I don't know if I fit in anywhere."

Ann's motherly instinct was to say, "Sure you do, Nate." But, honestly, she wasn't sure what he was referring to. He told her he had to get up at 6 a.m. to drive back to Stillwater for practice, so she left the subject alone. She figured she'd revisit it later.

Back on campus, Nate could tell Sutton was trusting him more. Nate had been spending extra time at the gym with Kyle and Nate's roommate Fredrik, working on his game, hoping to get meaningful minutes. Only Fredrik, a starter out of Sweden, knew how close Kyle and Nate were, and, at those sessions, Kyle would tell Nate what Sutton was looking for.

Finally, late in a Jan. 6 game at No. 24-ranked Texas, Sutton nodded for Nate to go in. There was about a minute left, the Texas lead hovering at about five points, and Kyle couldn't bear to watch. "He's about to go in, and I grab him by the shorts and I say, 'Hey, you ready for this?'" Kyle recalls. "He goes, 'I was born ready for this.'

"I'm scared to death. I'm thinking, 'God-dang, he's going to turn that thing over six times in a minute.' The place is packed. It's Oklahoma State-Texas. Great rivalry. But he served himself well."

Zane and Ann had witnessed it all, having driven to Austin from Edmond. They couldn't wait to hug Nate. But he seemed rattled afterward. Zane asked him what was wrong, and Nate told them he'd had a dicey flight to the game the day before. He told them that the weather had been foul, that the four-seat airplane he was in hadn't handled the turbulence well. Nate had bumped his head. He wasn't looking forward to the flight back.

"I told him he could ride home in the car with Ann and I," Zane says. "But he would never ever think about that. I mean, he was like, 'I'm on the team, I'm going to be with the team. So don't even go there, Dad.'"

Then Nate walked to the team bus, carrying his red pillows.

Jan. 14, 2001

My Nate,

There is nothing left to say. You're a father's dream.

An exchange of fate

Sutton surprised Nate again about a week later when he invited him to appear on his weekly TV show. The bright lights had Little Nate a bit jittery. He explained to the audience that he wasn't as talented as some of the other guards and that he got by on pure heart. Sutton grinned.

Before signing off, Sutton gave a sincere thank-you to the university donors who supplied the team with the "Cowboy Fleet" -- a group of private airplanes the players and staff took to road games. For years, going back to his days at Arkansas, Sutton's teams had always traveled in groups of three or four smaller planes. The idea was to get in and out of town quickly, so the players wouldn't miss class. Because the planes were donated, it also saved the program millions of dollars.

Nate generally didn't care what he flew. All he'd ever wanted to do was travel and play -- and now that dream was coming to fruition. The next tough road game was at Colorado on Saturday, Jan. 27, and on the way out to Boulder, the team rode in three separate aircraft. Nate got to fly out on a relatively new corporate jet; Sutton flew on another new corporate jet; Kyle took one of the team's longtime standbys, a 1976 Super King Air Turboprop.

Gottlieb adored that King Air. The pilot, Denver Mills, would invite him to observe the cockpit, and Mills' wife would always leave homemade cookies for the passengers. There'd also be goody bags left on each seat by a group of female students called, "The Spurs," which made the trips home, especially after a loss, more tolerable. They would poll players on what they liked to read, and one trip, Gottlieb found a Tom Clancy book waiting on his King Air seat.

The other planes were filled with goody bags, too, but just didn't seem as intimate. The only downside with the King Air was that it was about a half-hour to 45 minutes slower to its destinations. But on the trip to Boulder, Kyle didn't mind. He was, as usual, chumming around with the team's director of basketball operations, Pat Noyes; having a laugh with media relations coordinator Will Hancock and student manager Jared Weiberg; and picking the brain of trainer Brian Luinstra; giving updates to play-by-play broadcaster Bill Teegins and radio staffers Tom Dirato and Kendall Durfey. Mills and his co-pilot Bjorn Fahlstrom delivered a safe flight, and the group was ready to play the Buffaloes.

The game developed poorly. The team was a step slow, behind by double digits almost from the beginning. Nate didn't play, didn't get his ticket. Late in the contest, the Cowboys hit a 3-pointer to pull within 10. Sean Sutton, Eddie's son and his top assistant, turned to Kyle and said, "I guess the score won't look as bad on the highlights back home."

No surprise -- Eddie Sutton was perturbed. The team had quick turnaround games at Texas Tech and home against Missouri, and he wanted Kyle to break down the Colorado film right away and start scouting the Red Raiders and Tigers. The head coach told Kyle to switch planes with Nate, that Kyle needed to get back to Stillwater as swiftly as possible. So he went to find his cousin.

Nate was somber about the defeat. "We played bad, didn't we?" Nate said. "Sorry we lost." Nate was like a coach in that way; he hadn't turned the page yet. Kyle told him, "Hey, you and I are switching planes." Nate didn't bat an eye.

Because it was the slowest plane, the King Air was scheduled to leave Jefferson County Airport first. The same passengers climbed aboard, except Nate had replaced Kyle and his teammate Daniel Lawson had replaced Dirato, who had a bad back and was moved to one of the plush jets. Kyle remembers walking out to the hangar to check on the 10 of them and can still recall seeing their faces through the airplane windows. It was 5:18 p.m., dusk, when the King Air took off. A light snow was falling.

Sutton's plane left minutes later, and Kyle's corporate jet should've been right behind them. But before they took off, the pilot stopped the engines and offered food to all the passengers. That normally wasn't the protocol, and Kyle remembers thinking the pilot seemed out of sorts. Kyle needed to get back to grade the film; he started getting antsy.

When Kyle's jet arrived in Stillwater, Eddie Sutton was still at the airport. Kyle asked Sean, "Why is your dad still here?"

"He probably wants to make sure everybody gets back," Sean answered.

Kyle looked around, noticed the King Air hadn't arrived. He approached Eddie and asked where the plane was.

"Oh, they had mechanical problems, and they had to land in Garden City," Sutton said. Then the coach started rehashing the lousy game.

The pilot of the corporate jet then walked up, and Kyle asked him, "Hey, where's that other plane?"

Sutton said, "Kyle, I told you -- they had mechanical problems.''

The pilot said nothing and left, so Kyle followed him into the restroom. He asked him again about the King Air, and the pilot ignored him, didn't respond. Kyle's radar went up. He grabbed his cell phone and called Nate. Straight to voice mail. He called Noyes. Nothing. He called Weiberg. Nothing. He called Luinstra. Voice mail. He called Nate again. No answer.

He hopped in his car to go home; he had to start grading that film. He phoned his father, Ed, and while they talked, his call-waiting flashed. The number belonged to a woman he was dating, who happened to work at a local TV station. He didn't have time to chat and ignored it. She rang him again and again, and his dad told him to just take the call. When Kyle picked up, she was sobbing.

"You're alive!''

"Why wouldn't I be alive?''

"We got a report out of KUSA in Denver that your plane went down and there's no survivors.''

"Huh?''

He kept his bearings, went into coach mode. He told her the plane just had mechanical problems and hung up. He called Sutton and said, "Hey, Coach, I just talked to someone at the TV station and that third plane you said had mechanical problems crashed outside of Denver. Zero survivors."

Sutton didn't answer right away. His voice was unsteady. He said, "Oh my gosh, that explains the message from the NTSB [National Transportation Safety Board] on my answering machine."

They all met at the basketball offices, the staff and players. Eddie Sutton says he slipped out of the room to weep for a few minutes, then returned knowing he had to call the families of the victims. He says he thought of Nate and Daniel, the players who switched. He switched people at the last minute all the time, and he says he wasn't going to blame himself because if he hadn't switched them, two of his other dear friends would have died.

Back in Edmond, Zane and Ann were watching a movie and had not heard the news yet. Eventually, their phone rang. It was a casual friend of theirs, asking whether Nate had taken the trip to Colorado. Ann told her yes. The woman grew upset. She told Ann there'd been reports of a plane crash. Ann dropped the phone, and, when Zane heard the news, he dropped to his knees, praying it was a mistake.

The next phone call was from Ed Keller, Kyle's dad and Zane's brother-in-law. Zane picked up, and Ed told him, "Zane, I'm sorry to tell you, but the plane did crash, and Nate was on the plane. They're all gone."

Zane curled up into the fetal position and wailed.

The Sutton Story

Tom Friend tells the story of the impact the plane crash had on Oklahoma State coach Eddie Sutton and his family.

In an interview with Bob Ley of "Outside the Lines," Bill Hancock and Doug Gottlieb discuss their connections to the Oklahoma State plane crash 10 years ago.

Kyle sat in Eddie's office, watching him dial family after family. He remembers being struck by the enormity of that. At some point, late that evening, Sutton got around to phoning the Flemings. The call was brief; they were already numb.

Kyle had spent much of the night comforting the players on the team -- that was his job -- but he knew he desperately needed to see the Flemings in person. At 2:30 a.m., he climbed into his car for the 45-minute drive from Stillwater to Edmond. He had to tell them the truth, had to tell them that he had switched planes with Nate. The gravity of that began to seep in. He should've been dead, not Nate. He and Nate had traded seats and lives, and he had no idea how Zane and Ann would deal with that, how he himself would deal with their reaction. "I was sure they were going to hate me," he says.

He called it the longest 45 minutes of his life, and as he pulled up to their pristine home, surrounded by a golf course, he braced himself for the worst kind of pain. "My biggest fear walking into that house was anger and bitterness toward me, and they had every right to feel that way," Kyle says. "I was expecting it. I almost wanted it. Felt like I needed it.

"I was ready for any ammo, any bombshell, anything anyone wanted to throw at me. I'm ready. Give it to me. Sarah and Drue are still in their early 20s; they're still young. Zane and Ann had just lost their youngest child, their boy, their namesake. I'd done a lot in life. I was 32. Why not me? I switched seats with their son. I mean, I felt terrible. I felt terrible."

He entered the house, and Ann solemnly hugged him. Earlier in the night, Sarah had fainted, and Drue -- Nate's closest confidant -- was alternately inconsolable and furious, just at the way she'd lost her "Goody."

Kyle walked to the master bedroom, looking for Zane, and found him sobbing uncontrollably in his bed, still curled in the fetal position. He hugged him; the crying never stopped. He told him about the switch. There was little reaction from Zane. It didn't matter. What was done was done. Nobody hated Kyle … except Kyle.

Feb. 14, 2001

My Nate,

What a day to begin: Valentine's Day. I do love you so much. I thanked God again this morning for the brief 20 years I had my arms around you. You were such a light in my life. I'm like Gracie [the family dog]. Every time I would see you, my tail would wag and my heart would beat incessantly.

I think about you every few minutes during the day. Little flashes of your face at age 3 or watching you jog in front of me this past year. I can see you winking at me or you sprawled all over the green couch with both red pillows covering your face … Your team is set to play OU in Stillwater tonight. What a great event this will be. We're riding up for it. I gave your sisters and mother prayer journals for Valentine's Day. Thought they might like to write you, too. Later …

Love,

It's not as if Zane and Ann wanted to be out in public at the Oklahoma State-OU game, but the closer they were to the court, the closer they felt to Nate. Zane used to live just to see Nate on the bench. He'd watch the Cowboys on TV, waiting for sideline shots of Sutton and the team -- and there would be Nate, clapping his hands. Zane wanted to be near the bench again.

Zane already had asked Kyle to get him a tape of every game Nate had suited up for, just so he could see his face again. And Kyle got it done. Kyle would do anything for the Flemings, and he gave them choice seats to the OU game.

It was a Cowboys blowout, another emotional home victory. After the 10 funerals were over, the team had gotten back to the business of basketball and, in its return game, had taken down a strong Missouri team. Fredrik Jonzen had worn Nate's practice jersey under his uniform that night and scored a career-high 26 points, pointing to Zane and Ann throughout. Other players wrote "RIP, Lil Nate" on their ankle tape.

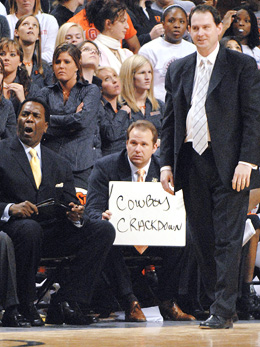

The Oklahoma game, a 72-44 rout by OSU, felt just as special, and late in the game, there was a scattering of people chanting, "Nate … Nate," knowing Sutton would've sent him in. Someone even wrote, "Nate got his ticket," on a cardboard message board at the arena.

After the Missouri game, Kyle had cried tears of joy walking off the floor -- he and the team needed that game to release their pent-up emotion. But after the Oklahoma game, Kyle went home to his empty apartment depressed. He wasn't sleeping, had a perpetual head cold and had lost weight. He should've been in therapy, but he didn't see Sean or Eddie doing it, either.

Ann made sure her family jumped into therapy ASAP, which was not a moment too soon. She kept thinking about her last visit with Nate, on New Year's Eve, and how he'd told her, "I don't know if I fit in." It made her cry, just thinking about it. Maybe he was trying to tell her something; she thought maybe he knew he wasn't meant for this world.

Everything, at this point, was a rationalization. What other choice did she or Zane have? Every day brought some heart-wrenching moment. For instance, a family friend went to pick up Nate's car, a Toyota 4Runner, at the Stillwater airport, and they found the red pillows he'd forgotten to take to Colorado in the backseat. Ann gave one to Drue and one to Sarah as mementos, which was traumatizing to have to do. They'd also received Nate's Visa credit card bill in the mail. They had given him the card his freshman year in case he ever needed anything at school, and in a year and a half on campus, Nate had used it only three times. He'd bought a belt, he'd taken a date to dinner and he'd bought his roommate Fredrik a steak. The total: $160. "You know how many people take advantage of their parents' Visa?" Ann says. "Not Nate."

Zane was urged by therapists to keep writing his notes to Nate, though he wasn't sure he wanted to … until one day, rummaging through Nate's belongings, he found a box. And then another box. And then another box. They were all of his letters from over the years. Nate had read them. He had lived by them. Zane was in tears, and to keep himself going, he needed to keep doing something more for Nate. For one, he decided he needed to change the way Oklahoma State traveled.

In the weeks and months after the tragedy, it was determined that electrical failure, not inclement weather, had caused the crash. Pilot error was also mentioned in the NTSB report. But what was most disconcerting to the families was that the 25-year-old plane had a history of power problems and hadn't been thoroughly inspected before its Jan. 27 departure. According to NTSB and FAA documents, there had been 89 instances of electrical problems on the plane from 1986 to 2000. Lawsuits were filed. The Flemings received a relatively small amount of money ($300,000) because Nate was a 20-year-old without dependents. But Zane got real gratification out of chairing a committee to change OSU's travel policy. It took him eight months to get it done, but he and his committee members made sure no OSU team would fly in a turboprop again.

The new policy prohibited the program from using prop planes or borrowed planes; the basketball team could fly only 32-seat airplanes or bigger. Also, if an athlete was apprehensive about getting on any team aircraft, the school had to find alternative transportation. That last part, Zane made sure of.

It healed a little bit of a wound, and, back in Stillwater, the players on the team were forever grateful. Some of them were not faring well, emotionally, Jonzen being one of them. He was rummaging through Nate's drawer one day when he found a notebook. He opened it up and saw the note that Nate had tucked away after the Elite Eight loss to Florida.

It read: "Nate Fleming, the starting point guard at Oklahoma State University.''

March 28, 2001

My Nate,

My heart aches so bad that I can't write today. I feel as though the air has been sucked out of me. I'm leaving tomorrow to go to San Antonio with your buddies Uncle Ed and Kyle. We're going to play golf and eat a lot. You should be on this trip. I'm so jealous that Ed has sons that adore him and that he can "live life with.'' I don't know how I'm going to go on without you, Nate. I would cut off both my legs for just the chance to hold you again. I hope God has his big arms around you and entrusts you like I did. If I could just hug you once more.

ESPN analyst Doug Gottlieb recalls how he learned that the OSU plane had crashed, and how "The Ten" will always be remembered.

The golfing trip helped slap some more weight back on Kyle. They ate lobster, they ate red meat. Zane didn't want Kyle to dwell on the switch, but deep down, Kyle says that he was suffering, that he was "in survival mode." Every day in the arena, he'd look up at a banner in the rafters that read, "We Remember." Every day, he'd walk by a bronze sculpture of a kneeling Cowboy, mourning The Ten.

To say Kyle was confused is an understatement. The Flemings had never resented him or blamed him, but why couldn't he get an ounce of peace? He decided that he should probably leave Oklahoma State, that there were too many reminders of Nate and his other nine friends. The only reason he stayed was that he felt connected to the players, wanted to be strong for them. Fredrik needed him, especially.

"By staying, I think I wanted to make sure I honored those guys," Kyle says. "I think Coach [Sutton], too, he wanted to make sure that, hey, No. 11 [Nate's number] wasn't worn anymore, that No. 3 [Daniel Lawson's number] wasn't worn anymore. Those type of things. They don't retire jerseys at Oklahoma State, but No. 11 and No. 3 weren't going to be worn under the Sutton watch. The Suttons and myself were there to ensure that."

Kyle could talk to his own father about his issues. But there was someone else he began to call after every basketball game, and almost every other day: Zane. They needed each other. Even if Kyle wasn't Nate, he was a younger male to offer advice to. Even if Zane wasn't Kyle's dad, he was someone to reminisce with about Nate.

Kyle began visiting the Flemings regularly, and when he'd stay over, he would walk slowly, tentatively to the back room … and sleep in Nate's bed.

"Kyle just manned up and came into this house and was there for us -- honestly, looking back -- in a way that no other person was," Ann says. "Zane needed boy time, and having Kyle around to talk sports. … I'm so grateful that [Kyle] did this for us. We needed him to love us and we needed to grieve with him and we needed him to allow us to grieve with him. The more we needed him, the more I think he needed us."

Slowly, there came a sliver of healing, and in 2004, the same year Oklahoma State reached the Final Four -- a galvanizing moment -- Kyle met a woman named Chaunsea who was easy to talk to and made him realize there might be a reason his life was spared. He was soon engaged, and the people who threw their engagement party were the Flemings.

Kyle showed Chaunsea Nate's room.

April 17, 2004

My Nate,

Easter was so difficult to get through. I was asked what you meant to us and what we miss about you. I don't know where to start. If only for just a short time I'm here on earth, you were the best son any man could have. You were the best friend any man could have. I will continue to spread the good news about you and the impact you have made on earth in 20 short years. I can't write anymore. I'm going to give up this journal for now …

My son, I love you.

Zane was a grandpa now; there were new notes to write. His oldest daughter, Sarah, gave birth to a son, and when she asked whether she could name him Nate, her sister Drue said, "No, no. I've got dibs on Nate as a first name."

Easygoing Sarah said fine, and named her son Jack Nathan. Nate could be his middle name. Zane and Ann were touched, ecstatic.

But back in Stillwater, there was still fall-out from the crash. In February of 2006, Eddie Sutton fell while walking to his car, climbed to his feet and proceeded to drive. He then struck another car, swerved into a tree and was not only charged with a DUI, but admitted taking prescription medication. He'd had previous bouts with alcohol, and he and his son, Sean, both admitted the crash had likely led to a relapse. The coach was forced to take a medical leave, later resigning. The head coaching job went to Sean.

Kyle remained in Stillwater as part of Sean's staff, but Sean was still reeling from the crash, too. He had never sought counseling, and nightmares had led to insomnia, which led to an addiction to anti-anxiety pills and painkillers. He lasted only two seasons on the job, and, in 2008, the entire staff was out on the street with him.

Kyle called Zane to tell him he was jobless, but they both were curiously upbeat. Here was Kyle's chance to start fresh, to do something for Nate, to touch someone else, somehow, some way.

"I hated that our staff left," Kyle says, "but it was almost like a relief. It was time for me to break away and time to start a new path professionally and personally. It was the greatest nine years of my life, but at the same token, it was the hardest nine years. Do I know exactly why I wasn't on that plane? God tells me every day. He shows me every day why I wasn't on that plane. I got to make a difference in kids' lives. I've got to make a difference in my family's life. I have to make a difference in hopefully the Flemings' life. That's why I am here."

By then, he and Chaunsea had a daughter, and were willing to move anywhere. Soon, Kyle received a phone call from Kansas coach Bill Self, a Cowboys alumnus who had met Kyle when Kyle was a student assistant at OSU. The only opening Self had was for a video coordinator, and Kyle accepted the offer. Kansas was coming off a national title. He'd be dealing with the nation's best players. Maybe he could help the program in some redeeming way.

So, after a sloppy practice one day, Kyle told some of the Jayhawks about a kid who never loafed, a kid named Nate.

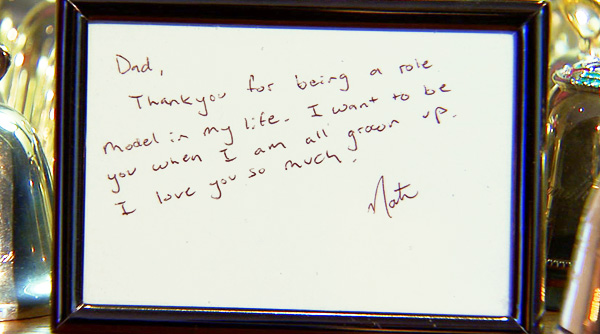

Dad,

Thank you for being a role model in my life. I want to be you when I am all grown up. I love you so much.

Nate

Nate's name lives on

Ann was digging through a stray box one day when she found this note from Nate. It wasn't dated, but the sense she had is he'd written it when he was 12 or 13, about the time Zane had begun sending his love letters to Nate.

She had presented it to Zane on a recent Christmas, and he'd bawled his eyes out in front of a number of people. Later that night, he took a stroll to the back bedroom. He shut his eyes and began reliving it again.

Not long after that, Zane received a phone call from Kyle. His nephew seemed upbeat, but a little anxious. He asked him what was up.

"Chaunsea's pregnant again,'' he said.

"Fantastic news, Kyle,'' said Zane.

"So, listen. We're going to have a boy, and we'd like to honor Nate. We'd like to name him Kemper Nathan Keller. I hope he can be half the boy that Nate was."

Zane broke down again. There was no closure eight years later, nine years later or 10 years later. Zane and Kyle decided that there never would be closure, that maybe the lessons of Nate, the daydreams of Nate would have to do.

When Kemper Nathan turned 1, Kyle knew the little guy would be special. For instance, the baby always climbed out of his crib and curled into Kyle's bed. Kyle knew that letting him stay set a bad precedent, that he should put a stop to it. He called Zane on the phone one night, just to chat, and the sleeping issue came up. He asked whether he should just lock the master bedroom door and force little Kemper Nathan to stay in his crib. He asked whether he should just let the baby cry all night in his room.

There was a pause.

"No,'' Zane said to Kyle. "Let him in your bed. Let him in your bed as long as you can. As long as you can.''

Join the conversation about "Dear Nate."

-

Kendall Durfey, 38

Kendall Durfey was a producer and engineer for the university's radio network, and a supervisor for OSU's Educational Television Services. A native of Hyde Park, N.Y., he also worked on the Eddie Sutton Coach's Show.

-

Bjorn Fahlstrom, 30

Bjorn Fahlstrom, the plane's co-pilot, was a native of Kalmar, Sweden. After three years in the Navy, he moved to Oklahoma City in 1996 to learn to fly and had been flying corporate jets for about a year and a half.

-

Will Hancock, 31

Will Hancock, son of BCS executive director Bill Hancock, was in his fifth year at OSU as a coordinator of media relations.

-

Daniel Lawson, 21

Daniel Lawson was a junior guard from Detroit. He'd played sparingly his sophomore season, then was a back-up who played in 17 games as a junior.

-

Brian Luinstra, 29

Brian Luinstra, a native of Augusta, Kan., was an athletic trainer who had worked two seasons for the men's basketball program.

-

Denver Mills, 55

Denver Mills, from Oklahoma City, was the pilot of the charter flight and had flown Oklahoma State athletic teams for several years.

-

Pat Noyes, 27

Pat Noyes was in his second season as director of basketball operations. Before that, he'd been an administrative assistant for coach Lefty Driesell at Georgia State.

-

Bill Teegins, 48

Bill Teegins was the play-by-play voice for Oklahoma State football and men's basketball broadcasts, and had served as sports director at KWTV in Oklahoma City.

-

Jared Weiberg, 22

Jared Weiberg, who had joined the team as a walk-on from Tonkawa, Okla., became a second-year student manager for the men's basketball team. He was a newphew of then-Big 12 commissioner Kevin Weiberg.