Deep In The Heart

How does Charlie Strong plan to revive a storied program in the nation's biggest fishbowl? By hooking top recruits, shooting straight and taking no bull.

THE ANGELO FOOTBALL CLINIC is a three-day Mardi Gras for high school football coaches, an only-in-Texas operation featuring a never-ending stream of lectures and PowerPoints and question-and-answer sessions on the best way to prepare your big'uns to pick up a line stunt. The clinic is held in mid-June, in the basketball arena at Angelo State University, and to reach the stands it's necessary to pass through a mazelike trade show, a cubicled left-right-left haunted house of gimmicks and gear.

It's booth after booth of men and women hawking a better artificial turf, a better video system, a better helmet, a better ankle brace. They've got jerseys, letterman jackets and chin straps. There's a training tool that looks like a reverse straitjacket intended to keep a quarterback's throwing hand eternally above his waist. There's a new and improved blocking shield worn like a vest. ("Keep your hands free!") There's an enormous plastic cylinder filled with sand being marketed as a leg-drive trainer by former Texas All-American and NFL All-Pro defensive tackle Doug English, who says he was inspired to invent after watching his son roll round hay bales on the family ranch.

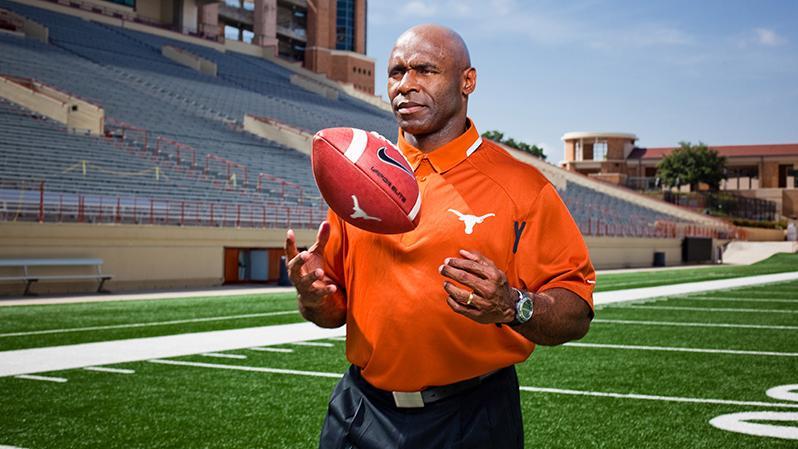

Into this windowless dungeon of earnest hucksterism strides Texas football coach Charlie Strong, flanked and followed by several assistants. Strong's Longhorn-orange polo is buttoned to the neck, just tight enough to leave no doubt about weight-room habits that produce forearms funneling from four-lane below the elbow to two-lane at the wrist. His shaved head shines brightly under the fluorescents, the Mississippi River of veins running from above his right ear. Barely 5-foot-8, looking 10 years younger than 53, Strong is the kind of man whose posture -- a chiropractor's dream -- seems to have its own personality.

His presence creates something of a stir, and his bearing -- upright and formal -- prompts everyone around him to stand at attention while he shakes hands and poses for photos and makes all the right introductions. He listens patiently to the reasons that each of the products laid out before him is destined to revolutionize the game. He tells coaches he'll be on the lookout for that big sophomore when the time comes.

After telling one high school coach, "You come down and visit us," he passes a booth extolling the virtues of a flat-sided football -- which allows receivers to throw it against a wall and practice solo -- and shakes hands with English.

"Everybody keeps asking me if I've met Charlie," English says. "I have to tell them I've met him so many times I'm already sick of him."

Strong laughs along with the joke and says, "I've gotta be as many places as I can, you know? Gotta keep moving."

THE FIRST BLACK head coach of any male sport at the University of Texas is something of an anomaly. He studied under Lou Holtz, considers Bear Bryant an influence and yet encourages his players to dance and trash-talk, within reason, if it suits their personalities. The "Core Values" he posts on the wall of the locker room include NO DRUGS, NO GUNS and TREAT WOMEN WITH RESPECT. Since March, Strong has cut loose seven total Longhorns -- including five in the last two weeks -- and suspended three others who failed to fall in line. He tells parents of potential recruits, "Your son will graduate, win championships and become a better person." He is the oldest of the old school, except in the areas where he is the newest of the new.

After two hours of roaming the halls in San Angelo, Strong retires to what amounts to a greenroom, happy for the quiet. Today, as he does every day, he woke up at 4 a.m. after four or five hours of sleep and was on a five-mile run by 4:45. (He alternates five- and six-mile runs six days a week, then rests on Sunday with an hour on the elliptical. "My runs are my time," he says.) Sitting in a desk chair in the greenroom, he prepares for a 20-minute speech by looking absently at a couple of index cards. Defensive coordinator Vance Bedford interrupts by asking him to speak to a recruit on the phone.

Suddenly quick and demonstrative, Strong takes the phone and reels off a series of questions: "What are you doing, cap'n? ... How's your hand? ... When are you going to come back and see us? ... Tell your mom I said hello."

The transformation -- Strong in repose to Strong engaged -- is startling, as if he summoned some ancient skill. The phone call is tangible. The phone call is real. The phone call is work.

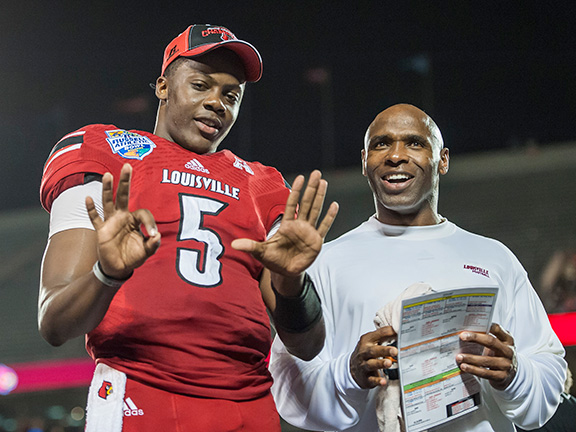

There is no doubt the man can recruit: He persuaded topflight players from South Florida, including Teddy Bridgewater, to attend Louisville. There is no doubt the man can coach: He earned unqualified endorsements from former bosses Holtz and Urban Meyer. Still, the all-encompassing atmosphere at the Angelo Football Clinic symbolizes the central question surrounding Strong as he prepares for his first season in Austin:

Can he handle the job?

Strong and QB Teddy Bridgewater ran up a 23-3 record at Louisville over the past two seasons. Romeo Guzman/Cal Sport Media/AP Images

THE HEAD COACH at Texas leads a culture as much as a team. The job is to coach and recruit and schmooze, mingle and glad-hand and sell. And Charlie Strong is taking over after 16 years of some of the best schmoozing, mingling, glad-handing and selling the college football world has ever seen.

Mack Brown was an icon of the culture, a one-man public relations campaign. He was folksy and charming, his words stretching out like one long taffy pull. He made time for everyone, from the most inexperienced reporter to the biggest donor. He was a master politician at a time when circumstances -- the rejiggering of the Big 12, the destruction of the rivalry with Texas A&M, the advent of the Longhorn Network -- demanded one.

Strong's manner does not lend itself to casual interplay. He is disciplined, ordered, linear. He is concerned mostly with reviving a program that hasn't reached double-digit wins or gone to a major bowl in four years. He seems to be in a perpetual hurry, perhaps a quirky byproduct of his overly long tenure as an assistant. He struggles to suffer fools, as he showed in San Angelo when a halting, unprepared and clearly intimidated local reporter was left to fend for himself as he attempted to formulate a coherent question. During conversation, Strong can occasionally retreat to inner thoughts, detaching from the moment to make a mental note before re-engaging, giving the impression that his words are undergoing a constant edit. And you can bet he'd rather hunker down over a practice plan than feign interest in a newfangled mouthpiece any day.

Holtz, who hired Strong as defensive line coach at Notre Dame and as defensive coordinator at South Carolina, says, "Charlie's not a chairman of the board. He's not a glad-hander. Mack Brown was chairman of the board, and he was great. Charlie is very involved with football and the players. He will do what has to be done to be successful."

The world Strong now enters is vastly different from the one he left. He got his first head-coaching job four years ago, and he rebuilt Louisville, winning 37 of 52 games, including the 2013 Sugar Bowl over Florida. He coached in topflight facilities and graduated his players at a rate that approached wizardry. He took over a program in 2011 that was stripped of three scholarships because of academic failings and turned it into one of two schools, along with Texas, with a perfect academic progress rate. He was hired by Texas a few months before three of his Louisville players were drafted in the first round and, for the first time since 1938, no Longhorns were drafted at all.

But when it comes to demands and expectations, Texas makes Louisville look like a cornfield Division III school. The number of media members who cover the Longhorns, from every portal and platform, can be overwhelming. That throng now includes Brown; the former coach turned down a benign title at UT to become an analyst for ABC. Strong says Brown, who declined to be interviewed for this story, told him, "It's your team now. Go run it."

On the topic of Brown the commentator, Strong laughs and says, "If I don't take care of my business, then they have a right to critique me and say what they need to."

Coaching at Texas can feel like yelling into an endless series of echo chambers. Portions of every practice are televised live and subsequently regurgitated on myriad message boards. Brown allowed Longhorn Network cameras in as he addressed his team at the end of each practice. Bank on this: The new guy, who often limited his players' exposure to the media at Louisville, will not allow such intrusion. "Everybody's asking, 'How's he going to handle the media?'" Strong says. "People don't really approach me. They think, 'If we ask, he won't give us an answer.' But I've given them answers. It's no issue to me at all. I'll talk when I need to talk."

His speech to the high school coaches at the Angelo clinic, a tight 20 minutes without notes, was occasionally disjointed as it hit his recurring themes. "The thing about young people is that they're always watching you and reading you to see what you're really all about ... because if you don't trust yourself, they're not going to trust you."

Shortly thereafter, an ESPN blog quoted unnamed coaches criticizing Strong for not tailoring his speech to high school coaches (although he clearly did) and for leaving San Angelo quickly after he finished. One coach went so far as to say: "He obviously didn't want to be here." They were apparently unaware of the two hours Strong had spent glad-handing before his speech and the fact that he requested to speak and shoehorned it into his schedule. No matter, he is the coach at Texas, and the perception of his performance -- unfair as it may be -- was viewed as a victory for every other Division I coach in the state, none of whom made his way to San Angelo.

Can he handle the job?

Maybe there's a more pertinent question: Is there any possible way to prepare for it?

text

Strong's mentors say the coach is more taskmaster and less chairman of the board. Michael Thomas/AP Images

STRONG GREW UP in Batesville, Arkansas -- a town that might well fit inside Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium -- as the son of a high school basketball coach and a house cleaner. He learned to work at his uncle's service station, back when working at a gas station meant pumping gas, checking oil and washing windshields.

In 1982, a year after wrapping up his playing career as a defensive back at Central Arkansas, Strong was a 22-year-old graduate assistant at Henderson State who had never ventured beyond the Arkansas state line. He sat across from HSU coach Sporty Carpenter, who was on the phone with a man in Florida named Dwight Adams, a Gators coach looking for a grad assistant.

"I got one for you right here," Carpenter said. "Name's Charles Strong, and he's a good one. Hard worker."

Carpenter hung up and told Strong, "You're going to the University of Florida."

"Where's Florida?" was the only thing Strong could think to ask.

"Don't worry about it: Just go," Carpenter said. "You leave tomorrow."

"Who am I going to meet?" Strong asked. "What am I going to do?"

"Don't worry about it," Carpenter repeated. "Just go."

And so Strong got on a plane the next day. Looking back now, he says, "Coming from where I came from, you knew this: You could not fail. You couldn't go back. I had to make it work."

Batesville, like most small American towns, is insular and scrutinizing. Coming back a failure, in Strong's eyes, would be worse than never leaving. So he landed in Gainesville and set about the long, hard task of never going back. He bought a stack of spiral notebooks and carried one everywhere. He took it to meetings, to the practice field, home every night. "I wouldn't write down much X's and O's," he says. "It was about how people taught and felt. Different approaches to players. What type of player you're looking for. What makes the great great. It starts with trust: someone trusting you and you trusting in someone else."

He broke down film obsessively and lived in the dorms and ate in the dining commons and studied for his second master's degree in education. He saved $8,000 and bought his first car, a Nissan Pulsar. He spent his nights typing up his notes and arranging them in files he still has in his office. And somehow, he found time to meet his wife, Vicki, while he was working at, of all places, a Florida football camp.

On the practice field, Strong watched the coaches grow frustrated with the scout team, hollering to "Do it again!" and "Give us a look!" He studied the way the players slumped, and their performance worsened with every harangue, and he summoned the courage to tell head coach Charley Pell, "Just let me handle it. I promise it'll work." Pell figured what the hell, and Strong began building relationships with the scout-teamers and outlining realistic expectations. For the rest of the season, he led a more effective and harmonious scout team.

"He could always read people," says Texas offensive coordinator Joe Wickline, who was a graduate assistant in Florida with Strong. "He was insanely organized. He had a structure and a plan, and he stayed with it."

For many, Strong -- the first black football coach in Texas' 121-year history -- represents not just a football coach but another toppled barrier. Anthony Drew Smith

Every step created another point of no return. The graduate assistant's job at Florida meant never having to go back to Batesville. The first coordinator's job meant never having to go back to being a common assistant. The first head-coaching job meant never having to go back to a lesser program.

"He had him a plan," Adams says, "and it worked."

Strong's work as a defensive coordinator at South Carolina under Holtz and at Florida under Meyer made him a fixture on the list of potential head coaches. During Strong's time at South Carolina, Holtz remembers getting a call from "a major school" telling him it was about to announce Strong's hiring. "The next day, they hired someone else," Holtz says.

Throughout his coordinator years, Strong wondered whether race played a role, or whether he was hurt by being a black man married to a white woman in a college football culture hog-tied to the status quo. "He should have been a head coach much earlier than he was," Holtz says. "I'm not saying it's race. I just know he should have been a head coach before he was."

To even get a chance, Strong felt he had to be better than everybody -- more disciplined, more prepared, more organized. "Once I made the decision that I was going to coach," he says, "I made up my mind that I had to do everything the right way." If he could give his players a better chance of graduating by setting up a rotating schedule of classroom visits by coaches, he'd do it -- and make some rounds himself. If he could gain a greater level of respect by jumping into running drills with his players and keeping pace with them in the weight room -- "He can probably handle a lot of us in there," says senior cornerback Quandre Diggs -- he'd gladly sacrifice sleep to train.

text

Anthony Drew Smith

Strong does not shy away from the uniqueness of his situation. A white coach can succeed or fail on his own merits, devoid of any cultural significance. But Strong, a black man stepping into a job held by a white man for the past 121 years, must walk a tightrope. For many, he represents not just a football coach but another toppled barrier.

Strong also understands the importance of sure footing. His first balancing act came when influential Texas booster Red McCombs -- signs for "Red's Zone" are among the first things you see in the stadium -- expressed his displeasure with Strong's hiring by calling it "a kick in the face. ... I think he would make a great position coach, maybe a coordinator."

Many viewed McCombs' comments in a racial context. "It really didn't hurt me," Strong says. "He's an alum who's given a lot of money to this program and university. A lot of times people want to know what's going on, and maybe he thought he didn't know.

"He and I talked. Went to dinner with him. Went to his office."

"Did he apologize?"

Strong hesitates, the internal edit at work. "Well, he said, 'The statement wasn't really toward you.'"

Much of the job, for Strong at least, might be found within that balancing act. He is fond of paraphrasing and personalizing Deuteronomy by saying, "I drink from a well I did not dig." It is his way of paying homage to those black coaches who came before him and weren't fortunate enough to make $5 million a year as the leader of the richest program in the country.

"I think about how many African-American coaches have not been able to be in the position that I'm in," he says. "And yet they're so happy to see it happen. They think, 'That's me sitting in that position.'"

Can he handle the job? Depends on your definition. In one of Strong's first meetings with the Longhorns, he stood before them and pointed out -- player by player -- what he knew about them. Nothing was spared, not poor practice habits or after-hour propensities or intrasquad squabbles.

"He was letting us know he'd done his research," says Diggs. "He ain't gonna hide anything. If you're part of this family, you're going to hear everything."

After the Longhorns finished spring practice in May, new quarterbacks coach Shawn Watson interviewed every player from the offense. Center Dominic Espinosa had a question of his own:

"Is Coach Strong really that real?" Espinosa asked.

"Oh, yeah," Watson said. "Every day."

STRONG IS SITTING in the conference room adjoining his office in Austin when a question prompts him to get up and leave the room. He walks through the door to his office and returns seconds later with a manila folder labeled "Lou Holtz Notes." The pages inside, nearly 20 years old, are pristine, crisp, dated, ordered. They look like they just came back from the dry cleaner's. Strong starts thumbing through the echoes.

From Oct. 16, 1995: We will challenge our players today that they will be embarrassed by USC. Tomorrow we start convincing them they can win this game.

Strong laughs when he finishes reading the entry. "Coach Holtz psychology," he says. "I still use it."

"Don't the players catch on?"

He looks up from the paper and lowers his voice: "The smart ones do."

Strong continues to leaf through the pages, past pithy acronyms -- ACT: Attitude Changes Things -- before stopping to read a quote from Holtz: Frustration is not having anyone to blame but yourself.

He returns the folder to a drawer in his desk and sits back down in the conference room. The opposite wall, the one staring back at him, depicts the view from the tunnel inside Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium on a Saturday afternoon. It's a bright day on the wall, perfect for football, and 105,000 people are standing, their bodies turned to face the tunnel, equal parts anticipation and expectation. The scene is why you strive to coach at a place like this, why you take notes and run every morning before dawn and do whatever it takes to never go back.

Strong looks at the wall, a wry smile on his face.

"See that crowd up there?" he asks. His eyes never leave the wall as his voice slows and drifts toward a murmur. It is barely audible when he says, "You know what they say. The eyes of Texas are always upon you."

Tim Keown is a senior writer for ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at Tim.Keown@espn.com. Follow him on Twitter (@TimKeownESPN).

Follow The Mag on Twitter (@ESPNmag) and like us on Facebook.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader

Join the conversation about "Deep in the Heart."