|

THE FIRST BELICHICK  More than one Belichick, it might surprise you to learn, has left a mark in pro football. Long before Bill was leading the Patriots to glory, his father Steve was starring at fullback for the 1941 Lions. But that’s not the best part of The Steve Belichick Story. The best part is that he began that season as the team’s equipment manager. More than one Belichick, it might surprise you to learn, has left a mark in pro football. Long before Bill was leading the Patriots to glory, his father Steve was starring at fullback for the 1941 Lions. But that’s not the best part of The Steve Belichick Story. The best part is that he began that season as the team’s equipment manager.

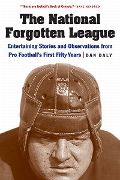

It happened like this: Steve had just graduated from Western Reserve University in Cleveland, but he couldn't get a high school coaching job because he’d already been classified 1-A by the draft board. (Translation: He might be here today, but he could be gone tomorrow.) So when Lions coach Bill Edwards, his old coach at Western Reserve, offered to let him tend to the Lions’ socks and jocks, Belichick jumped at the chance. At least it would enable him to stay around the game. “You know how they paid the equipment man in those days?” Belichick once told me. “You're not going to believe this. Each player chipped in a dollar a week. And there were, what, 25 or 30 guys on the team?” At the beginning of the season, maybe. But if things didn't go well for a club in those days, it often released players -- that is, dumped salaries -- and went with a skeleton crew. The previous year, after a particularly disappointing loss, the Lions up and fired six players. As then-coach Potsy Clark explained it, “We can lose just as easily with 25 men as with 31.” Actually, Edwards had more in mind for Belichick than just blowing up footballs. Detroit was running the same offense Western Reserve had used, an old-style single wing that revolved around the fullback -- which happened to be Steve’s position. So in addition to his other duties, he helped with the coaching, showing the Lions fullbacks the various steps. One of those fullbacks, a Notre Dame grad named Milt Piepul, had trouble handling the snaps from center. His hands were decent enough, but he was “blind as a bat,” Belichick said. “He was the first guy I was aware of who used contact lenses, and sometimes he had a hell of a time getting them in and keeping them in. That was a problem, because the fullback got the snap on every play except one in that offense.” (Contact lenses in 1941. What must they have been like? You’d think, on a football field, they could do as much harm as good. This, remember, was the pre-face mask era, and punches in the puss were a weekly occurrence. In fact, that same season, the New York Herald Tribune reported the following: “Frank Kristufek, [Brooklyn] Dodger tackle, who wears contact lenses, got a terrible black eye [against the Giants], but the lens was removed unbroken from his eye.”) But on with our story. As the months passed, Belichick became a more active participant in practice -- to the point of even running the plays. And when the Lions got off to a 1-2-1 start, Edwards said, “Heck, Steve can play fullback better than any of these other fellas” -- and put him on the active roster. In his first game Detroit got demolished by the Bears 49-0. But in his second, against the Packers, he scored his team’s only touchdown on a 77-yard punt return ... and became a minor sensation. “We were in three-deep [to receive the kick]," he said. “It wasn't a real good punt. The ball hit the ground, took a lateral bounce, and I just took it on the run. There were only a few guys up the field that I had to beat. The last one was the punter, and it wasn't too hard to fake him out. “When Bill [Belichick] went to Detroit as an assistant [in 1976], he tried to get a copy of the game film for me. I’d never seen it. But the Lions didn’t have it. Later I spoke to [Green Bay GM] Ron Wolf, and he dug it out of the Packers’ archives. He sent it to me with a note that said, ‘That was one hell of a run you made.’” Belichick was now making $115 a game -- a big improvement over his equipment manager’s pay. Granted, Whizzer White, the club’s franchise player, was pulling down “800 or 900 dollars a week,” he said, but $115 was still pretty good dough. “You could buy a new Ford back then for 600 dollars. Things were cheap. I was paying a dollar a day to stay at the Hotel Saverine [in downtown Detroit].” Two weeks later in New York, Belichick came off the bench to score two touchdowns in a 20-13 loss to the Giants. The Associated Press’ coverage of the game began thusly: NEW YORK, Nov.10 -- After getting a load of Steve Belichick busting a line, an engaging question today around the campus of Tenth Avenue Tech -- better known as the New York Football Giants -- was “who called that football player an equipment man?” The Detroit Lions had little enough to roar about in the 20-to-13 mudbath the Giants handed them in the Polo Grounds yesterday, but No. 1 on the list was the work of Socker Steve, who came out from among the head-guards and hip-pads in the locker room to score both Lion touchdowns on line smashes, pick up 26 yards in four cracks, run a kick back 46 yards, intercept a pass and generally show he had a better idea of what the business was all about than any other back on the club with the single exception of Whizzer White. From then on, Belichick was a starter. It wasn’t all fun and games; Bears ruffian Dick Plasman broke his nose with a vicious forearm one afternoon. But if the war hadn’t come along -- after which he veered into college coaching -- Steve would have been happy to keep playing. Only Whizzer scored more TDs for Detroit than he did that year (three), and no other back on the team came within a yard of his 4.2 rushing average. (And the yards came hard for the Lions. They gained fewer of them than anybody in the league.) Belichick’s now-famous son is named after Edwards, Steve’s coaching mentor -- and the man who made him the most celebrated equipment manager in NFL history. Indeed, the only gripe Steve had about his pro career was that the football encyclopedias listed him at 5-foot-8 or 5-9, 190 pounds. “I was 5-10 3/4,” he said. “And I weighed 193.” Looking back from a distance of 70 years, he seems larger still. Excerpted from “The National Forgotten League: Entertaining Stories and Observations from Pro Football's First Fifty Years” by Dan Daly, by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. © 2012 by Dan Daly. Available wherever books are sold or from the University of Nebraska Press 800.848.6224 and at nebraskapress.unl.edu. Click here to visit the book’s Web page.

|