The Charcuterie Board That Revolutionized Basketball

In the past three years, the Warriors have won two NBA titles with the most explosive offense in history. This is the inside tale of how it all began -- on a plate of appetizers.

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Oct. 30 NBA Preview issue. Subscribe today!

The sanctuary for the early check-ins, the merely laid-over and the maddeningly delayed is tucked between Gates 25 and 26 in Terminal 2 at Oakland International Airport. It's called Vino Volo, Italian for "wine flight," and it offers some 200 labels of the former, in advance of the aggravations of the latter.

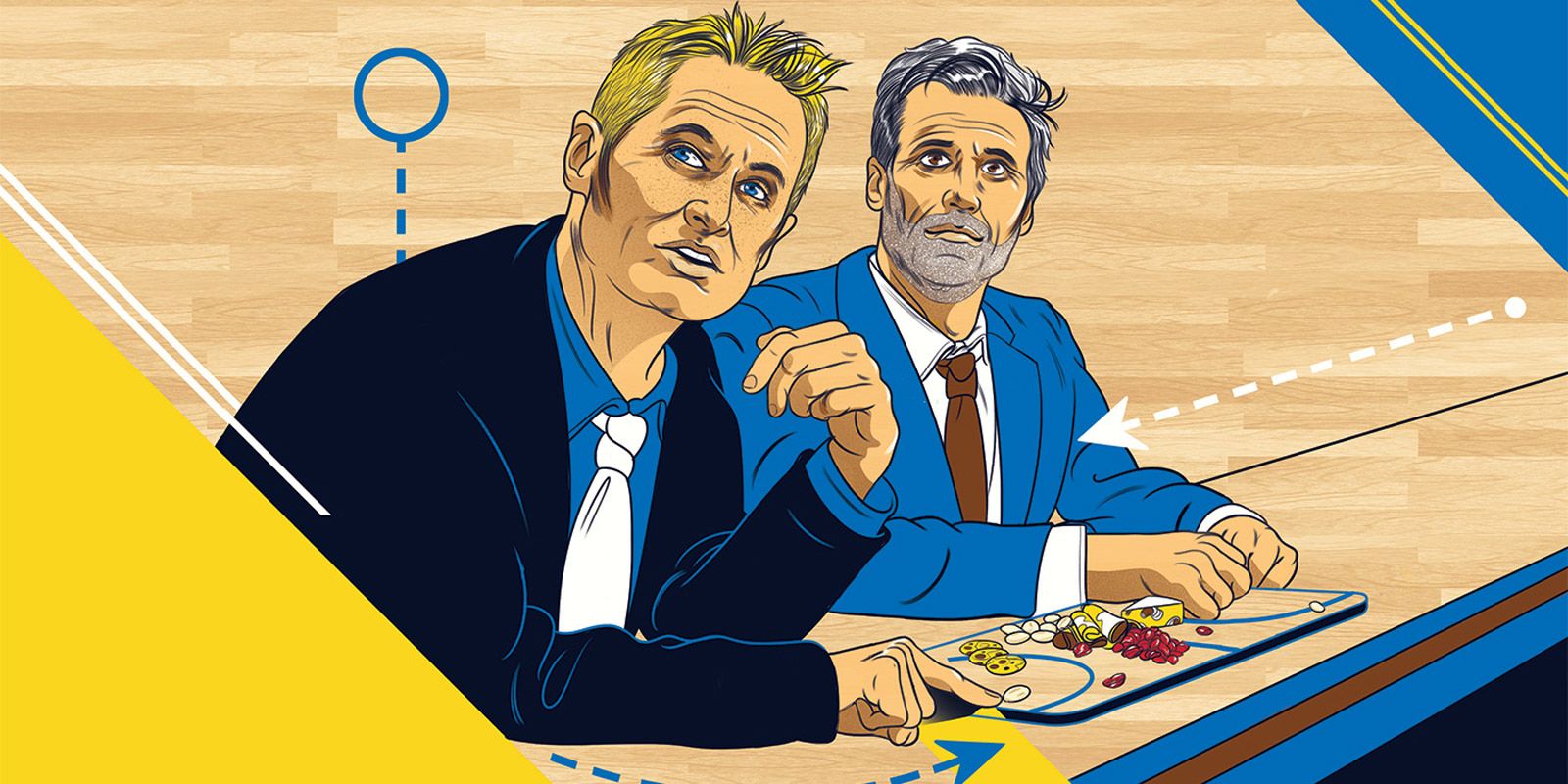

It's 3:30 p.m. on a Friday in early August 2014 when two middle-aged men -- both conspicuously tall, both with the loping grace of ex-athletes -- commandeer chairs at the end of Vino Volo's five-person bar. Seconds later, back in the kitchen, Kevin Ninkovich hears a shout from a colleague on the floor: Steve Kerr just sat down.

Ninkovich, a 28-year-old bartender at Vino Volo, is a Warriors obsessive. Growing up as a 5-foot-and-change guard, he even imagined himself as Kerr: a deadeye who lacked physical gifts but could drill a title-sealing trey if called upon. Now here the man is, the Warriors' new coach, named to the position just 10 weeks prior, sitting alongside his old college teammate and newly named assistant Bruce Fraser.

Ninkovich is not about to let this chance slip away.

After another staffer takes their order -- two glasses of pinot noir and a three-meat, three-cheese charcuterie board -- Ninkovich preps it and bounds out of the kitchen, armed with an agenda. Ninkovich's fandom stretches back to the 1990s' "Run TMC" era, when Tim Hardaway, Mitch Richmond and Chris Mullin were the NBA's highest-scoring trio. Ninkovich loved how that team moved the ball and is no fan of the scheme installed by Kerr's predecessor, Mark Jackson. Jackson's Warriors had won 51 games the season before but had averaged just 247 passes per game -- not merely the worst mark in the NBA that season but 15 fewer than the next-closest team. When those Warriors fell in the first round to the Clippers, Alvin Gentry, then a Clippers assistant, was left wondering why the Warriors played so much one-on-one, isolation basketball. Personnel-wise, they reminded Gentry of the mid-2000s Suns, an offensive powerhouse led by point guard Steve Nash: Golden State had the dynamic point guard, the lethal perimeter scorers, the forwards who could pass, the high-IQ playmakers. All they need, Gentry thought then, is the right scheme.

All they need, Ninkovich thinks now, as he delivers the charcuterie board, is the right scheme.

So Ninkovich, with a captive audience of Warriors coaches, musters the courage to speak: What are you going to do? He asks Kerr. Will our one-on-one offense end? Will you implement the triangle offense?

"Funny you should mention that," Kerr replies. "We've got some ideas. Here, I'll show you."

And then, as Fraser looks on, Kerr swipes clear the wooden board, casting the handle in the role of a basket. He positions the board's dried cranberries and marcona almonds into two five-on-five teams in a half-court setting, with the cranberries relegated to defense. Suddenly, Almond Stephen Curry, hovering near the top of the key, swings an imaginary ball to Almond Klay Thompson on the wing, then cuts to the near corner while Thompson dumps it down to Almond Andrew Bogut. Thompson and Curry set picks for each other along the perimeter, while Bogut weighs his options: find open almonds or back down his helpless cranberry.

These, Kerr explains, are aspects of the triangle offense, which he played in during the Bulls' 1990s heyday. But then Kerr pulls back, giving the noshes a breather. He notes that the Warriors would be foolish to run the triangle exclusively; it wouldn't best utilize their outside shooters. No, Kerr says. They'll run a hybrid.

These ideas have, for weeks, been rattling around Kerr's head. But he hasn't yet begun to diagram plays, or the scheme itself. Until now. And so for 10 minutes, Ninkovich watches as Kerr lays the foundation for the most devastating offense the NBA has not yet seen -- if only he could somehow turn the league's worst passing team into its best.

FOUR WEEKS LATER, the Warriors' new coaches are convening at a Napa Valley resort for a three-day meet-and-greet. There's tennis. There's swimming. There's plenty of wine. There's a croquet tournament that Gentry, now a Warriors assistant, will win (proclaiming, in the aftermath, "I'm the greatest black croquet player ever!" before stripping off his shirt and pouring Perrier over everybody). The mood is light, but everyone understands the scope of this task. Coaches exchange ideas, watch hours of film -- four sessions of three to four hours each. And it's here, with the preseason a few weeks away, that Kerr begins outlining the plan for his staff, the one that's been marinating throughout his career and began to fully ripen on that Vino Volo charcuterie board.

In Kerr's mind, it's both simple and radically complex. He envisions elements from Phil Jackson's triangle, which called for passing from all five players. He'd loved how that system used Bulls forwards and centers as passers, perfect for Bogut, David Lee and others. Still, he doesn't want to abandon the high-screen-and-roll actions Curry had used in prior seasons to rain down 3s. Instead of employing a full-on triangle, what Kerr wants is a blended system.

And there is much to cram into the blender.

In the mid-1990s, the Jazz, which his Bulls had twice faced in the Finals, tormented Kerr. Those Jazz would feed the ball to forward Karl Malone in the post before guards John Stockton and Jeff Hornacek would screen for each other, with the open player receiving the ball back from Malone. Those actions are dubbed "split cuts," and Kerr hated guarding them. To him, guarding movement is far more challenging than guarding isolation -- a "nightmare," he calls it -- and he envisions a similar nightmare for defenses guarding Curry and Thompson. It's also a matter of taste. "Iso basketball, where one guy is going one-on-one and everybody is standing around, I don't like that," Kerr says. "I don't like that at all."

On defense, the Warriors are stout, loaded with long-limbed forwards who can easily switch on any pick-and-roll. Kerr doesn't want to tinker with a squad that ranked third in defensive efficiency the season before. But offensively, they ranked 12th. Kerr knows that nine of the previous 10 NBA champs ranked in the top 10 in both categories. He'd told general manager Bob Myers that if they wanted to win a title, they'd need to do the same. Transitioning from heavy isolation to heavy passing and movement would be dramatic, but "there's a makeup in every player who's ever played," Kerr says, "that if you get to touch the ball and you get to be a part of the action -- whether it's as an assist man, ball mover, shooter, dribbler -- the more people who are involved in the offense, the more powerful it becomes."

As Myers puts it: "All of us want to be part of something."

Still, Kerr knows he has one problem -- and a vexing one at that: It's easier to persuade a bad team to evolve than one that just won 50 games. Kerr has seen new coaches slash and crash upon being hired; with a good team, he needs to tread lightly. As the eight-game preseason slate approaches, pressure is mounting. Normally, such games carry minimal stakes, a chance to tinker with lineups or plays. Teams don't try hard to win. Not so these Warriors, who are unveiling Kerr's dramatic new scheme. The coaches believe that they need to win, that it needs to work -- or they'll risk losing their players. And then there's this: For all of Kerr's experience in the NBA, he has zero experience as a head coach.

The Dubs' assists per game since Kerr arrived? The three highest rates in 20 years. Ezra Shaw/Getty Images

IF YOU WERE casting the role of Warriors metrics guru, Sammy Gelfand would almost be too on the nose. A bespectacled, scruffy-haired Chicago native, Gelfand, the Warriors' manager of analytics, was one of the few holdovers from Mark Jackson's staff. Still, Kerr and Gelfand are kindred spirits. Just as Kerr is the sort to diagram plays with snacks, Gelfand grew up doing similar things with his breakfast cereal, staging elaborate games between his Lucky Charms, keeping score, his mind always at work. And so it is that during the preseason, Kerr turns to Gelfand in search of a concise, gettable metric that can serve as a benchmark for the team and, in so doing, unite it.

When they sit down to analyze the previous season, in search of a Grand Unifying Metric, one figure stands out. "What about this one -- passes per game?" Gelfand asks.

Kerr considers it. It has potential. It fits right in with the culture he hopes to develop. He looks at Gelfand. "What's a good number?"

Gelfand knows the Warriors ranked last in the NBA in that category under Jackson in 2013-14. He also knows that many of their turnovers had come, counterintuitively, on possessions in which they passed the ball less than twice. The less they passed, the sloppier they played. He also knows that when they passed more than three times in a single possession, they led the league in points per possession on such plays. In essence, when the Warriors moved the ball, "we were," Gelfand says, "almost unstoppable." They just didn't do it very much.

Now, in search of their number, they analyze teams whose styles they want to emulate. The Bobcats, who led the league the year before with 338.2 passes per game? Nope. Too much of a leap. Besides, they barely posted a winning record. The defending-champ Spurs? Aiming for 334 passes, as the Spurs had the season before, was also too lofty. When the Warriors tracked their passes in preseason games using Kerr's new scheme, the squad routinely hit the 280 mark. And so over the course of the two-week preseason, a nice round figure was identified -- something easy to remember but challenging to attain: 300.

"CAN WE EVEN do this?" Myers wonders.

It's early November, and doubt is creeping into the mind of the Warriors' GM. His team has begun the season 5-0, but basketball-wise, it's a disaster. The Warriors are racking up turnovers like they're storing them for winter -- averaging 21.6 per game. That's not only the worst mark in the league, it's about five turnovers per game more than the worst team in the prior season and only a few off the worst mark in NBA history.

After each game, Gelfand has been feeding Kerr postgame statistical reports, and the first stats listed are always passes: passes per game, secondary assists, free throw assists, the number of possessions with zero to two passes, three to five, six-plus. In morning film sessions, while coaches show players 15 to 20 clips from the previous game, they also post passing totals. And indeed, the Warriors are hitting that 300-per-game mark -- averaging 320.8, in fact, through the first five games, eighth best in the league.

The good news, then? The team is passing. The bad news? They're overpassing.

"Don't pass for the sake of it," Kerr implores his team. "If you're open, shoot it. If not, pass it. But don't be stationary. Move!"

Still, it's a struggle, like a classical flutist trying to learn to play jazz flute -- onstage, in real time. In a Nov. 9 loss to Phoenix, the Warriors tally 26 turnovers -- 10 by Curry alone -- after also notching 26 the game before against Houston.

Curry, for his part, is relying on what Kerr calls "horrible tendencies" -- careless left-handed hook passes over the top of defenses -- but also doing something far worse: remaining stationary after making passes. Defenses are manhandling Curry, and Kerr tells his star to run from pressure, not fight it, that even a back cut without getting the ball is a productive play because he's taking the defense with him. Instead, Curry is, as Kerr came to call it, "dancing" in place -- and stopping their offense as a result. Meanwhile, Draymond Green, former second-round draft pick, is trying too hard to establish himself as one of the team's top playmakers. He'll show potential, then become frustrated if he fails. "Keep it simple," the staff tells the third-year forward. "You can make plays, but make the simple play."

For weeks, Kerr has harped on the turnovers. In August, Kerr had visited Seattle Seahawks coach Pete Carroll during his team's training camp and had seen, in the Seahawks' defensive meeting room, a football on a rubber handle attached to a wall; as players came in and out, they'd hit the ball, trying to knock it loose. Carroll believed the habit would cause more fumbles. Ball possession, Carroll preached, is everything.

For the first six games, in this regard, the Warriors have been a white-hot mess -- like a race car with a wobbly wheel. Game 7, Nov. 11, would be a date with the Spurs, defending NBA champions and the gold standard for ball movement. Kerr had played four seasons (and won two titles) under Spurs coach Gregg Popovich and had admired how the Spurs' passing helped foster a selfless, team-first culture.

"It wasn't just play your best five guys to death," Kerr says. "It was play everybody. You go deep into your rotation, even if it means losing a couple of games in the regular season, just empower everybody. It's kind of the beauty of basketball, the old cliché about the total being greater than the sum of its parts -- I believe in all of that. Five guys have to operate together, but the other seven on the bench, or nine, however many, they've got to feel part of it."

Revenge would also be a factor. The Spurs had beaten the Warriors in the playoffs two seasons earlier, then swept them in the regular season the year before Kerr arrived. "The reason we made all these changes," Gelfand says, "was to get on their level." From day one, Curry recalls, Kerr had talked about the Spurs and their legacy. Though the season is young, the Warriors know this game will be a measuring stick.

They do not measure up.

“It's kind of the beauty of basketball, the old cliché about the total being greater than the sum of its parts -- I believe in all of that.”

- Steve KerrIt begins well enough, the Warriors clinging to a 38-34 lead midway through the second quarter. But then the Spurs hit their stride. With less than a minute before halftime, forward Boris Diaw pump-fakes two Warriors on the perimeter, drives and zips the ball to Manu Ginobili on the right wing, who catches it with his left hand and in the same motion whips it to the right corner, where Tony Parker has enough time to do his taxes before swishing a 3-pointer. Six seconds of perfection.

After halftime, the Spurs cash in on more sloppy Warriors turnovers -- an errant pass by Curry, a fumble by Green. By this point in the season, Kerr has seen so many mistakes that he's been repeating, repeatedly, the phrase: "We're just slingin' the ball around out there!" It's like a mantra. Or a koan. He's saying it so much that his wife, Margot, has begun chiding him for it. And that's what Kerr sees against the Spurs: more carelessness, more slingin' the ball.

The Spurs, who feature the same Big Three -- Tim Duncan, Ginobili and Parker -- as they had when Kerr played beside them a dozen years before, cruise to a 113-100 win. In the locker room, Kerr explains to his deflated team that it doesn't matter that the Warriors had outshot the Spurs. Not only had they lost the turnover battle, 19-8, they'd lost their focus. "Look, guys," Gentry adds, "you don't want to say it, but this is how we want to play. This is who we want to emulate."

It's an enigma -- and a conundrum. They need to play with pace but protect the ball. They need to play unselfishly but not too unselfishly. Pass the ball, but don't turn down a great shot.

"Can we do that?" Kerr asks.

"The main goal," Steph Curry says, "is to just make the defense make as many decisions as you can so that they're going to mess up at some point with all that ball movement and body movement and whatnot." Ezra Shaw/Getty Images

IT'S JUNE 13, 2017, 24 hours after the Warriors have won their second championship in three years. They've humiliated the Cavaliers in five games, and Vino Volo in Oakland International Airport is abuzz, as usual. Wine unites everyone, Volo's staffers like to say. But it's seats C1 and C2 at the end of the bar, where Kerr and Fraser sat on that August afternoon, that to them are now legend.

Lawrence Flores, a 36-year-old assistant manager, was working the floor that day, stealing peeks at Kerr's demonstration. He's told the story a dozen times to friends and family. "That could've been the creation of this offense," he tells them, "That could've been the start." When Ninkovich, now 32, watches the Warriors, he sometimes sees not players but cranberries and almonds.

After their loss three seasons ago to the Spurs and inspired by the manner in which San Antonio had filleted them, the Warriors went on to win their next 16 games. "It was," Kerr says of that Spurs loss, "the best thing that could've ever happened to us." Pre-Spurs loss, the Warriors had ranked last in turnover percentage, with Green amassing more turnovers than assists. The rest of the season, they would rank sixth in turnover percentage, with Green averaging twice as many assists as turnovers.

And the epiphany arrived just five days after that Spurs defeat. By virtue of a schedule quirk, the Warriors were granted a four-day break after a road game against the Lakers, and when Kerr entered the visitors locker room at Staples Center before tip-off, he proffered a deal: "Play the way we've been talking about and play the right way -- take care of the ball, defend, do all that stuff -- and I'll give you the next two days off." The players literally gasped in disbelief.

That night, there wasn't one moment, or a singular play, but a river of them -- a constant flow, the ball pinballing around the court, side to side, to the tune of 343 passes. "Beautiful," Kerr says, thinking back on it. The Warriors scored a season-high 136 points.

In the days prior, what Kerr had most wanted was to know that his words were being heeded. "You just want to know the ship is heading in the right direction," he says. And as he watched the rout unfold, he saw everything he had been preaching, his players carrying out his vision with focus and flair.

The transformation was radical -- and ruthlessly effective. By the end of the season, the Warriors ranked second in offensive efficiency and first in defensive efficiency. They averaged 315.9 passes per game, nearly 70 more than the season before -- the second-biggest leap in the league. They had the highest increase that season in assists per game and secondary assists per game, and the second-highest jump in assist-to-turnover ratio. They would go on to win an NBA-record 73 games the next season, falling one win shy of a second consecutive NBA title, and Curry would win his second straight NBA MVP award, just as Nash had done in Phoenix exactly one decade earlier in the offense that so inspired Kerr.

The Warriors ultimately found that if defenses were panicked about the first pass, by the time their third pass arrived, they were rewarded with a wide-open corner 3. "The main goal," Curry says, "is to just make the defense make as many decisions as you can so that they're going to mess up at some point with all that ball movement and body movement and whatnot. But it took awhile for us to kind of get the understanding of where each other was going to be without having to call a set play or whatnot. So it took awhile."

Actually, it took eight regular-season games.

It took. And it held: The Warriors today claim the three highest assist-per-game averages of the past two decades. And all have come in the past three years. "I can't sit here and say we knew this was going to happen," Fraser says, "but if I go back and read Steve's thesis on what he wished for, it's very close to what happened."

Consider: Since the start of the 1995-96 season, nine of the 10 best teams in offensive efficiency were either the mid-'90s Bulls (where Kerr played), the Nash-led Suns (where Kerr managed) or Kerr's modern-day Warriors. Kerr's basketball journey weaved through offensive greatness, and then he built his own.

"It was like it was destiny to have Steve come in and try to coach that way," says Luke Walton, former Warriors assistant coach, "because they were built to play that way."

And after two seasons alongside Kerr, soon after Walton agreed to take over the rebuilding Lakers, the new coach announced to his team that he wanted to create a nightly goal. He wanted something to establish a culture. Something to make everyone feel a part of a whole. Luke Walton wanted 300 passes a game.