A Man Apart

All Russell Westbrook needed to make history was to be left alone. This is the untold story of how he found his singular drive.

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's March 27 Analytics Issue. Subscribe today!

You're all alone, little man, and you're starting to think it was a mistake to board that plane. Ever since you walked off that jet bridge, people have been asking questions with their expressions: How did you get here? Who told you to come?

You're a skinny 16-year-old taking a trip by yourself for the first time, and you flew 2,100 miles from Los Angeles to Atlanta for a basketball camp, only to be told nobody knows who you are. The guy driving the shuttle from the airport to the hotel couldn't find your name on the players list, so you stand on the curb holding your suitcase and your confusion, deciding what to do next.

You've got the hotel's address on a piece of paper and enough money for a cab ride, and you're determined to get it straightened out.

This camp is one of the big ones for high school players, sponsored by a shoe company. You're here because your coach made a call, and he believed in you enough to convince someone important -- someone you are right now trusting actually exists -- that you belong here with all the best high school players in the country.

You get out of the cab and walk up to the camp's check-in table at the hotel, trying to look like you belong, trying to ignore the buzz in your head that says you might not. "Westbrook," you say. A lady runs her finger down the lists of names, flips through the papers with a concerned look and then starts back at the top. She asks again, and you try to keep it light by saying, "Westbrook -- always at the end." You're trying to be cool, even as she winces. "Honey, I'm so sorry -- you're not on the list."

You ask her to please check once more. She looks up at you with kindness, seeing your eyes widen in panic, and shrugs.

You make a phone call. "Coach, I'm not on the list." Back in Los Angeles, Reggie Morris doesn't sound all that surprised. "Sit tight," he says. "I'll figure it out."

And so you sit. And you wait, shifting your too-big, size-14 feet under your too-small, 6-foot body to shed the nervous energy. Hours pass. Just you and your suitcase. You watch the other players -- the ones everybody here knows just by looking at them -- leave their rooms and pass through the lobby on their way to the gym.

It's like these other guys are a different species. From where you sit, the entitlement comes off them like a smell. They have boxes of recruiting letters from all the top-shelf programs. They'll get smiles and bro-hugs from every tracksuited coach who swaggers into the gym. They're on a first-name basis with the shoe-company reps whose life goal is to compliment 16- and 17-year-olds long enough and loud enough that someday they'll sign up to wear the right logo.

You? You have letters back home too. You can count them on one hand.

Here's a dirty secret: You're a few months away from your 17th birthday, about to be a senior in high school, and you can't even dunk. You're getting there, though, you can feel it. The workouts with Pops -- running the dunes at the beach, shooting at Jesse Owens Park near the house in Lawndale -- have you closer to the rim. The hours spent shooting what Pops calls the cotton shot, a soft pull-up jumper that incongruously appears at the end of a full-speed drive, have given you a sneak attack against anyone bigger and stronger.

Four hours later, someone from the camp walks toward you, smiling. "All set," he says, handing over a shirt and a pair of shorts. The shirt goes to your knees, each armhole wide enough for both legs, and the shorts billow like a parachute when you run. You hold them out in front of you. "Sorry, that's all that's left," the guy says.

And so you show up to the gym late, and scraggly, and unknown, with Pops' mantra running through your head: Your only friend on the court is the ball. You wad all your anxieties and self-doubt into a ball and throw it at the court until a few of those important men in the tracksuits, unable to find you on the camp roster, feel compelled to ask who you are. It's not talent they're seeing but desire, and the sheer amount of space you manage to occupy with that 150-pound body.

The looks on their faces indicate something you've seen before, and something you'll see again: They have no idea what to make of you.

Over the past decade, Russell Westbrook has evolved from an overlooked college recruit to a potential NBA MVP.

The task of describing Russell Westbrook's play this season, his ninth in the NBA, is a challenge readily accepted but rarely completed. His style is portrayed as angry, or vengeful, or enraged, or ferocious, but when I ask him if he feels all those primal emotions when he's playing, he says, "Not at all. I feel fine."

It's a funny line, and he delivers it with suitable nonchalance. I feel fine. There's a rubber bracelet on his wrist that expresses his attitude toward just about everything: Why not? It's his slogan-turned-koan-turned-trademark. It describes his shot selection, his fearlessness, his wardrobe. So yes -- of course he feels fine. But he's not finished. He tilts that jaw, highlighted by whiskers that emerge like weeds through concrete, and says, "That's always the perception, that I don't have control and that I'm mad. I don't know why people say that -- 'He looks angry, he looks mad.' No. I'm focused. I'm locked in on what's important, and the extraterrestrial stuff doesn't matter."

This first post-Kevin Durant season, this endless Jackson Pollock splashing across the court night after night, has been a refutation of limits and constraints. Westbrook, 28, was averaging an NBA-leading 31.7 points to go with 10.6 rebounds and 10.0 assists through March 6, putting him on pace to join Oscar Robertson as the only players to average a triple-double for a season. But the numbers belittle the experience. Throughout modern NBA history, triple-doubles have been memorialized, fetishized and sometimes trivialized -- but never before have they been normalized. It is a surprise whenever Westbrook doesn't get a triple-double.

"I think people miss the point," says Oklahoma City Thunder general manager Sam Presti. "The thing I'm impressed with isn't the statistical accomplishments. What he's doing is more a feat of mental toughness and mental endurance."

Westbrook is a statistical aberration who manages to resist quantification. Watching him live and looking at the numbers, or even the highlights, is as different as swimming in the ocean and taking a shower. He is playing every game like he doesn't trust it to be there tomorrow. He rebounds like a power forward, flies through the lane with a blatant disregard for his body and accelerates off the dribble like a Bugatti. Asked how big he feels on the court, Westbrook, at 6-3 and 200 pounds, says, "As big as I need to be." Everything around him seems to diminish, as if this normal-sized man has the power to shrink the world around him.

Durant's decision to sign with the Golden State Warriors last summer, after playing alongside Westbrook for eight seasons, triggered a highly unfulfilling pseudo-feud. It also, in unexpected ways, granted Westbrook a measure of immunity. Even after Westbrook signed a three-year extension with the Thunder in August, nobody knew what to expect. Everyone had an idea, of course: Westbrook, set free of Durant's electromagnetic force, would spin off into his own orbit. His worst qualities -- dominating the ball, taking bad shots early in the clock, force-feeding his teammates impossible passes in an attempt to rack up assists -- would awaken the caustic grandpa in every basketball purist. Oh, he'd get his numbers, but the team would suffer. After all, history has not been kind to teams that lose a franchise player: The 2010-11 Cavaliers won 19 games after winning 61 the season before LeBron James left for Miami; the Heat won 37 after winning 54 in James' last season in Miami; New Orleans won 46 in Chris Paul's final season with the team, 21 the next.

Given that litany of failure, it's tempting to say the Thunder, playing with an outlet-store roster in a bespoke world, are joining Westbrook in making some sort of history. They were 35-28 through March 6, and it would take a massive late-season collapse for them to fall below the seventh seed in the Western Conference playoffs. Westbrook has taken a deeply flawed team and bent it toward his will.

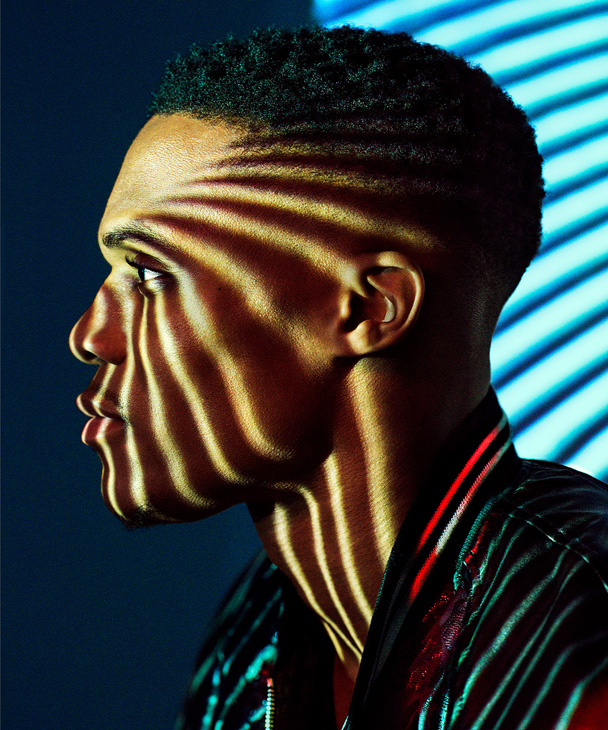

"I'm not really part of the club, but that's fine with me." -- Russell Westbrook Pari Dukovic for ESPN

You're in the gym, little man, sitting on the bench, all alone, watching a group of college and pro players go through weeknight workouts at Leuzinger High. You're here because Coach Morris came to you after your sophomore year and delivered the workout schedule and a message: These guys are using the gym, and they could use an extra body.

Outside the gym, there's all kinds of garbage going on, which is why you're not out there. You and your brother hear gunshots every once in a while, and the sirens and helicopters are part of the South Central soundtrack, but you know what and whom to avoid. Pops works with you at the park when he's not working at the bread factory, and your mom is always there to talk about anything but basketball. At school you find your group, the guys who want to play ball and get good grades, and ignore the rest.

Coach Morris sees all that and more: how much it means to you; how you get on teammates when they're late for class; how you walk across the street from your house to do chores for Khelcey Barrs' grandmother after Khelcey -- one of your best friends -- died of an enlarged heart after a pickup game the year before.

At the gym, you watch while Tony Bland, home after a season in a Russian pro league, leads a group of pro and college players through workouts. They need you only every once in a while, to stand in on defense in five-on-five drills, but when they call, you hop up like a hero, firing your skinny-as-a-flagstick body off the bench. They try to post you up, these grown men, and you widen your stance and hold your ground and use all your available leverage to keep them from scoring. They think it's funny, cute even, the way you try so hard when it's clear you don't stand a chance.

A year passes, you hit 6 feet, and the guys come back to the gym. This time around, they're having trouble scoring on you. At first they pretend they're going easy, trying to be nice, but then they start to dog each other:

Man, Little Russ stopped you four times in a row.

You mean you can't get a shot off him?

Soon they invite you into the drills. These grown men, even the pros, start to treat you as an equal.

Four years later, when you get drafted at No. 4 by the Seattle Sonics, Bland will be an assistant at San Diego State, and he'll be clapping and yelling in the basketball office when your name is announced. When everyone else in the room calls the pick crazy, Bland will stand up and announce, "They have no idea what they're getting."

The image that pops into his head when he hears your name called has nothing to do with the player you've become. It's you sitting on that bench, waiting for a chance.

In his ninth season, Westbrook has almost doubled his rookie output. Harry How/Getty Images

There is always a Westbrook moment, a sequence in every game that is not just seen but felt, the athletic equivalent of a needle plunge into an artery. Nobody will remember this one, but late in the third quarter of a blowout loss to the Clippers in Los Angeles on Jan. 16, Westbrook botches a two-on-one break by throwing the ball over Victor Oladipo's head. As the ball sails into the stands, Austin Rivers stands up off the Clippers' bench and claps derisively -- and Westbrook notices. He always notices.

The Clippers inbound the ball to Raymond Felton, who turns innocently upcourt to find himself staring into the face of biblical retribution. He takes one clumsy dribble and Westbrook slaps it away, toward his own hoop, as if throwing himself a pass. He rises from the right wing with the fury of a 19-point deficit, jackhammering the ball through the hoop and heading back down the court with an almost imperceptible sidelong glance at the Clippers' bench. Game lost; point made."That edge is always with him," says Thunder assistant Maurice Cheeks. "Maybe it comes from him growing up and always being the underdog, the feeling that he's always had to prove himself. He's certainly reached a point where he could let it go. It's incredible that he hasn't. But it's good. It makes him who he is."

There are small moments, plays that can go unnoticed in real time but, in retrospect, stress the unconventional nature of Westbrook's genius. The night before the Clippers game, Westbrook is forced to guard the Sacramento Kings' 6-8 Rudy Gay on a switch at the right elbow. He is 15 feet from the basket, stuck staring into the back of a man 5 inches taller and more than 30 pounds heavier. Just as the Kings identify their good fortune, Westbrook steps around Gay to get in front of him and flicks the entry pass away from Gay. It is a feat of agility and quickness, but it is also a glimpse into a remarkable mind at work. If he had held his position, Gay would have backed him down and shot an easy turnaround -- an unmemorable, entirely forgivable outcome. If Westbrook had jumped the pass and missed, Gay would have taken two dribbles and dunked, and Westbrook would have looked foolish. It's a risk he -- maybe more than anybody in the game -- is willing to take.

Westbrook is a compulsive organizer, thriving on order and routine. He brings his household bills and a stack of envelopes to the practice facility and pores over them at breakfast. "He'll be like, '$45 for this and $35 for that,'" says longtime Thunder teammate Nick Collison. "Details matter to him." He has his own shower and his own massage table in the team's training facility. He makes a pregame call to his parents on his way to the arena. He eats a peanut butter and jelly sandwich before every game, and it has to be cut in a precise diagonal. He says a prayer out loud to himself at the exact same moment of every national anthem, just as the song hits its final two lines. After introductions and before tip-off, he runs to a spot underneath the opponent's basket and pumps his arms three times, his thumbs pointing to his shoulders, as if to say, It's all on these. At halftime he gets his ankles re-taped, then changes into a clean uniform for the second half.

Similarly, there is a precision to his game that's easy to miss amid the attendant chaos. On Feb. 3, the Thunder come into a game against Memphis reeling after a lifeless 28-point home loss to the Chicago Bulls that followed a murderous stretch of playing 15 of 21 on the road. There is a murmur of doom in Chesapeake Energy Arena, a sense that this is where the fun ends and the season devolves into a quest for personal statistics and the highest lottery pick. The false assumption: Westbrook will be crazed and inefficient, ripping rebounds out of teammates' hands on one end and going one-on-five at the other. He will be enraged and vengeful and ferocious, the very embodiment of all the Westbrook stereotypes.

Instead, he takes six shots in the first half. The Thunder shoot 58 percent and lead by 10. "That's the antithesis of what people think of him," Presti says. "It would almost ruin the myth for people to find out he's not this wild card all the time."

The fourth quarter brings change, as is fitting for the player who is among the NBA's leaders in nearly every clutch-time stat. He scores 15 straight points in the final 2:34 to turn a 102-99 deficit into a 114-102 Thunder win. The triple-double (38 points, 13 rebounds, 12 assists) seems almost incidental. The obligatory MVP chants are so loud, the building feels as if it is moving, and Westbrook lets loose a full-throated scream and bounces off his teammates as he stalks the court. If you didn't know any better, you could have mistaken sheer joy for anger.

To watch Westbrook in that moment -- embracing the freedom, accepting the responsibility, absorbing the adoration -- is to reach a conclusion: This is a man who has gotten exactly what he's always wanted.

You get out of class and go directly to the Leuzinger High gym, a fading piece of brutalist architecture amid a vast ocean of concrete. Just like every other day, you grab a mop and push it around the hardwood floor until you've made a pile of all the paint chips that have floated down from the ceiling like confetti since your team's last practice. But on this day, during your senior season, you turn the mop at one end of the court and look up to see UCLA coach Ben Howland standing in the doorway. When Jordan Farmar makes a late decision to enter the NBA draft and Howland decides to offer you a scholarship, the mop is the first thing he'll mention.

From the moment you get on campus, you feel your inadequacy. You won't turn 18 until November, so your parents have to sign all your documents -- scholarship papers, medical releases, HIPAA forms. You spend almost your entire freshman season on the bench. Darren Collison and Arron Afflalo play ahead of you, and they take turns beating you up in practice. You don't question whether you can play at this level; you question whether UCLA is the place you should be proving it. You get tired of hearing yourself being described as reckless and wild and untamed, as if you're an unruly pet.

You get one start as a freshman, at West Virginia, and it goes poorly. A decade later, your former coaches will talk about that game, about how you were so overamped -- even for you! -- that you committed nine or 10 turnovers and fouled out. It will get blended into the many tales that make up your origin story, once it becomes clear that your stardom demands one. The problem is, the West Virginia story is not quite true. You were bad, shooting 1-for-11, but you had only three turnovers. You'll grow to understand the rules of mythology: The worse you can seem then, the better you'll seem now.

After your freshman season, you vow to never spend another game on the bench. You spend the summer playing in the famed pickup games at UCLA with and against NBA players such as Kobe Bryant and Baron Davis, but only after you've spent several hours in class and worked out three times.

In your sophomore season, you set a UCLA record for minutes played. You become known for dunks and defense. The NBA starts to notice. You're a late first-rounder, they say, and then things get really crazy. You decide to leave college -- "Leave? I feel like I just got here," you said the first time someone suggested it -- and gradually you move up.

The Sonics -- soon to be the Thunder -- request a private workout. They have the fourth pick. None of it seems real. Presti and a couple of player-personnel people make the trip to a gym in Los Angeles. They're sitting in the parking lot 30 minutes before the workout, wondering where you are. You've been sitting in your car for the past 45 minutes, not more than 20 feet away, studying for exams and wondering when they're going to open the gym.

Presti isn't entirely sure what to make of you, but in draft meeting after draft meeting he will repeat the same line: "I like this kid's story."

"That's always the perception, that I don't have control and that I'm mad. No. I'm focused." -- Russell Westbrook Pari Dukovic for ESPN

Thunder coach Billy Donovan has been talking about Westbrook for 20 minutes after a recent practice when he interrupts himself with a question: "You know what I love about Russ? I'm not ever standing in front of the team in the locker room before a game thinking, 'Oh, man, I really hope Russ is ready to play tonight.' I can assure you that's never happening."

To the observer, Westbrook is fascinating and enigmatic and at times evasive. Yet he has stripped the game down to its two most important and intimate elements: Did you try your best, and did you win?

"You have to understand something about Russell," says College of Idaho coach Scott Garson, a former assistant at UCLA. "If Russell wasn't getting paid however many millions he's getting paid, he'd still be playing basketball. He'd be killing guys in a pickup game at a YMCA somewhere."

Cheeks envisions the scene: "Could you imagine showing up and having a guy play like that?" he asks. "One time down the court and they'd say, 'Uh-uh, I'm outta here.'"

The idea that Westbrook is capable of playing any other way -- even in any setting -- is a consistent source of humor within the Thunder organization. He is a two-time All-Star MVP primarily because he doesn't seem willing to accept the concept of an exhibition. The imaginary night at the YMCA would undoubtedly end with him leaving the court, undefeated, without so much as a nod to anyone else in the gym.

He is perhaps the NBA's least accompanied and most independent superstar. He restricts his circle to his parents, Russell Jr. and Shannon; his wife, Nina; and his brother, Ray. He's not interested in doling out pieces of himself for the sole purpose of improving his image, and he acknowledges that his public perception has suffered because of it, most glaringly in February when he was not voted into the starting lineup for the All-Star Game.

"That happens," he says. "It doesn't worry me. Twenty years down the line, somebody might say, 'You weren't a starter,' and I'm going to say, 'It doesn't matter. It doesn't determine who I am or what I do or how I played.'"

It's a standard answer, safe and nonthreatening, as close to canned as he gets over the course of 45 minutes. But when I suggest that Steph Curry, who won the fan vote over Westbrook, is marketed differently, Westbrook cuts me off. "One hundred percent," he says. "One hundred percent. That's just because of how I play and what I do. It's just different."

His voice is a unique instrument, high-pitched and quick, sometimes difficult to read. "I'm not really part of the club, but that's fine with me," he says. "I'd rather be in my own club. S---, I'll tell you the truth: I'm OK with that. Everybody else can be part of the same club, and I'll be in my own club."

You stand amid a mass of humanity, and somehow you're still all alone. This time it's Sacramento, and the Kings, and an arena filled with people waiting to be amazed but wanting you to fail. You bounce to the music, pumping your arms three times, thumbs down. From your spot under the basket, you see them around the center circle, the other nine starters, pounding fists, hugging. This is their ritual, swords touching before the duel.

You see an old teammate from UCLA approaching, taking a couple of jog-steps in your direction. Darren Collison, maybe more than anyone, knows you don't commiserate before games, yet he appears to be raising his hand and heading your way.

You give him a quick half wave that is both acknowledgment and warning:

I see you; don't come any closer.

All these years later, they still don't know what to make of you. You're honoring a commitment, not necessarily to the fans or your teammates or your employer. They're all welcome to come along for the ride, but your obligation is to the competition. To compete is to live, and live now, and to prove whatever you have left unproven. Every game is a chance to stand apart, and stand alone. To hell with whatever is left behind.