OTL: The Burden of Being Myron Rolle

XFORD, England -- Oxford at first light is an ode to potential. The purple sky throws shadows off churches and their saw-blade spires, bringing definition to the gap-toothed smiles of crenellated walls. The ghosts come out in the dream of early morning. Twelve saints and seven British prime ministers walked these streets. So did Bill Clinton and John Donne, Sir Thomas More and Kris Kristofferson, plus the guy who invented the World Wide Web.

XFORD, England -- Oxford at first light is an ode to potential. The purple sky throws shadows off churches and their saw-blade spires, bringing definition to the gap-toothed smiles of crenellated walls. The ghosts come out in the dream of early morning. Twelve saints and seven British prime ministers walked these streets. So did Bill Clinton and John Donne, Sir Thomas More and Kris Kristofferson, plus the guy who invented the World Wide Web.

That little list? It always happens. People construct a roster of famous yet diverse alumni when describing Oxford -- the quirky sum even more fantastic than the successful parts -- implying that greatness comes with the diploma. But a shadow lurks near those collections of names. Oxford University is full of students who will one day change the world, yes, but it is also full of those who have the gifts to change it and will fail. In the hope of morning, though, let your focus fall on Clinton and Donne, More and Kristofferson and now, as the dreamy purple light burns off, as busses chug and belch down the ancient streets and another week of reality begins, Myron Rolle.

Rolle bounds down Banbury Road, long strides chewing up sidewalk, hurrying to his next lecture. Today's topic is "Pain and the Brain." He settles into a seat in the back of the room, the only student whose biceps strain against the fabric of his shirt. Around him, fellow Rhodes scholars open laptops, notebooks or leather-bound Moleskine journals. The professor, a world-renowned researcher, begins speaking, about Pavlov and the curious case of Phineas Gage. The students take notes furiously.

Rolle takes a few notes, too, but mostly he stares at the professor. The motors and gears in his head are spinning. This is how it's always been for him. His mind rarely stops computing; when his brother McKinley is throwing all the possible routes in random order during their regular morning football workout, Rolle just knows if they missed a 2, or maybe a 7. Today, he's focused on the man standing at the front of the room. What about this doctor? Where did he start? How did he immerse himself in the brain? When, and why, did pain come to interest him? Did he watch helplessly as someone he loved struggled against a devastating mental illness? Was it a wife? A child? What drove him to this very place at this very moment?

Suddenly, his focus shifts.

What about me? How did I get here?

Myron, who doesn't fail

A lifetime of unqualified successes, that's how.

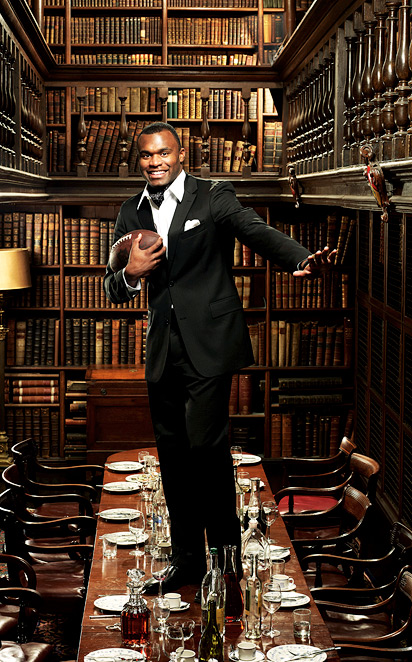

Whatever he does, he does it well and, to the immense frustration of others, with ease and grace. He's an All-American safety. He can play saxophone and sing. He was the lead in his high school's production of "Fiddler on the Roof." He graduated from Florida State as an exercise science major in less than three years with a 3.75 GPA. He shadows doctors, dreaming of medical school. He says "please" and "thank you." He researches stem cells. He starts anti-obesity programs that the U.S. Department of Interior adopts, aimed at helping Native American children make smart choices about fitness and health. He raises money for hospitals. Myron Rolle, it can safely be assumed, not only eats vegetables, he likes them. Life hangs comfortably from his shoulders like a fine suit.

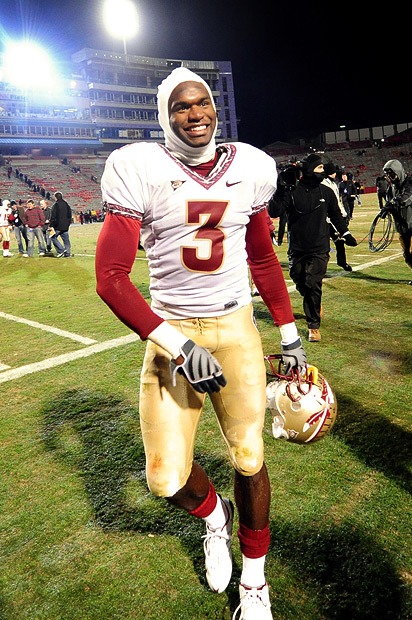

So, it's no surprise that during the 2008 football season he was named a finalist for a Rhodes scholarship, the most prestigious academic award given. Only, the deciding interview was scheduled for the day of a game at Maryland -- and the interview was in Alabama. No problem. SuperMyron would simply go to Birmingham, answer the committee's questions and still make it to the game by halftime. He might just leap a tall building while he was at it and keep right on going until he landed at midfield.

Nothing thrown at him by the interviewers shook him. He spoke with passion, threw in a joke or two and, at the end, stood there with a smile on his face. One of the judges winked at him. No need to drag out the suspense.

Another success. Rolle was chosen -- he soon would announce he was skipping his senior season to go to Oxford -- and minutes later he boarded a private jet, shadowed by reporters from both Sports Illustrated and the Chronicle of Higher Education. Halfway to Maryland, a crowd waiting to cheer his run out of the tunnel in garnet and gold, he put in his earphones and scrolled through his iPod.

What could provide the appropriate soundtrack for this kind of life?

Rolle chose two songs.

One was Ice Cube's "It was a Good Day."

But even that didn't seem to do his run of blessings justice.

The other one came closer, Frank Sinatra singing:

When I was 21

It was a very good year

TUESDAY

Tucked into a narrow alley off High Street, St. Edmund Hall breathes students in and out of the long stone tunnel that opens into the main quadrangle, as the college has done for 800 years. Young men and women mill around the lush grass of the quad, in the shadow of the sundial and the well, and at night, they drink beer and smoke in the cemetery out back. Rolle, who doesn't have time for the graveyard bull sessions, stops by to check his mail. Two unfamiliar envelopes poke out of his slot.

The first one is from Ohio. He tears into the envelope and finds a note: I read about you in The Times and I thought you might be interested in this article from the New Yorker.

It's a recent piece by Malcolm Gladwell, and it offers and backs up the theory that professional football is a lot like dogfighting and is, ultimately, a sport that cannot be played without doing serious damage to the brain. This is, obviously, a conundrum for Rolle: He wants to be a pro football player and a neurosurgeon. Don't successful careers in each of these preclude the other? Of all the obstacles facing Rolle, including the luck and work and genetic blessings required to be one of the 32 chosen to be a Rhodes scholar and one of the 32 chosen to be a first-round pick, perhaps none is greater than this: People in each world don't believe anyone could possibly be passionate about the other. He's always asked: Which do you like more? Draft gurus question his commitment. His defensive coordinator at Florida State, Mickey Andrews, told Rolle that he was spending too much time on school and not enough time on football. Even Oxford University assigned him to St. Edmund Hall, known here as the jock college.

The other letter is from a London teacher.

I heard you this morning on Radio 4. Never have I heard a young man so articulate, forward thinking and inspirational. All I could think about listening to you was: I have to get him to speak at my school. I'm a teacher in London at an inner city school where I do lots of work around raising black achievement. To hear you speak about the importance of education and hearing about your life decisions -- putting off the NFL for Oxford, wanting to be a neurosurgeon, money not being your main goal in life -- it would all mean so much to the kids at my school.

Rolle considers his mail. Two letters, two totally different problems; if other people's myopia is an obstacle, then the exact opposite is, too. He is trying to stay on course in a vast sea of possibilities, and everywhere he goes, he is confronted by people lining up to tell him what he means and what he could be and, most confining of all, what he should be.

He is a vessel for other people's dreams.

Myron, who knows what others expect

Q: What do you struggle with most?

A: I have not had tragic incidences in my life that have rocked my personal being. The thing that really has been my biggest enemy in this world has been pressure. And people. People who I love. People who look at me differently. The pressure is tough, man. I'm not gonna lie. It's the hardest part. Easily.

Myron, whose dreams keep growing

Here are the three things to know about Rolle as he reads that second letter:

1. The Monday after he won the Rhodes scholarship, his cell phone rang. Jesse Jackson. At first, Rolle thought it was a joke. But no, it was actually Jesse Jackson, and he wanted to tell Rolle this: "If Dr. King were alive today, he'd be proud of you."

2. While Rolle was in D.C. for the inauguration, Princeton professor and African-American leader Cornel West spotted him on the street and bowed. Literally bowed down and said this: "You are the future of black America."

Everywhere he's been, for as long as he can remember, he's been singled out for future greatness, by strangers and family alike. When he was in high school, riding on the New Jersey Turnpike with his dad, he asked one day, "What would it be like to be normal?" He's thought about that a lot.

And this, too: What is enough for those who see so much in him? He opens his e-mail and there's a recruiting pitch from the Harvard Business School. His dad wants him to make a perfect score on the Wonderlic given at the NFL combine. Jesse Jackson wants him to be a leader for an entire generation. Florida State told him on his recruiting visit that he could be a Rhodes scholar … and now he is. Mickey Andrews wants him to react, and his professors want him to think. He deals, on a daily basis, with the crushing weight of having this much potential. He worries about losing himself. He never stops thinking about what other people want for him, and how it's easy to become a mosaic of their expectations instead of staying true to his own. "The danger is that you lose a sense of identity," he says, "you lose a sense of who you are. If you continue to try to navigate through constructs that are set up by other people, by other people's thoughts of who you are and who you should be, you will never be personally at peace."

So he understands he shouldn't spend his life pleasing other people. But what does he want?

This brings us to …

3. A year ago, Rolle spoke at the College of the Bahamas. His family comes from the nation, and he alone among his five brothers was born in the United States (his mom traveled to Houston so he could be an American citizen). He was chosen before birth.

One of his many dreams is to open a medical clinic in his hometown of Exuma, and so, after the speech, the Bahamian politicians crowded around him. Be the prodigal son, they told him. Come back and be president one day. Be prime minister. When he returned to Tallahassee, he was online one night in his room and saw a photo tagged on Facebook of himself and the current president of the Bahamas. A lot of things ran through his head: People want me to come back and save their country? I don't know if that's in my plan. I never thought of politics. This isn't me.

Sitting there in the dark, he finally began to understand: There is no enough.

All he can do is stay focused on his dreams: NFL, medical school, then a life as a groundbreaking neurosurgeon and head of a foundation that brings medical care to those without.

You know, simple stuff.

Myron, who has set the bar high

Q: Has anyone ever said to you: "Myron, if you want to go to the NFL and have a long career and retire and live off investments, that's OK … it's your life"?

A: No.

He explains: "It's always, 'What's next?' I think people align themselves with my way of thinking when they're talking to me. They try to create new avenues for me to pursue, so if you want to be a doctor and you have interest in human rights and philanthropy and social equality of medicine and disease, why don't you think about being surgeon general? Then you could have a political impact, with a stronger influence and a bigger platform. I'm that person. 'What's next? What's next?'"

WEDNESDAY

There are mornings when none of it seems strange. The Iffley Road Sports Complex opens early, and a crowd of scholars who are also athletes wait outside. The sweatshirts and gym shorts place the toned men and women: rowers from Harvard, swimmers from Oxford, lacrosse players from Navy and, soon, one safety from Florida State University. Why does a man have to choose? Roger Bannister, who ran the first sub-4-minute mile on a track some 20 or so yards from this crowd, was also a doctor. Bill Bradley was a senator and is in the Basketball Hall of Fame.

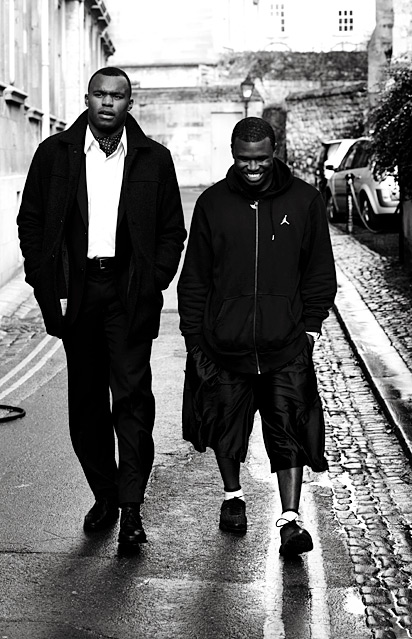

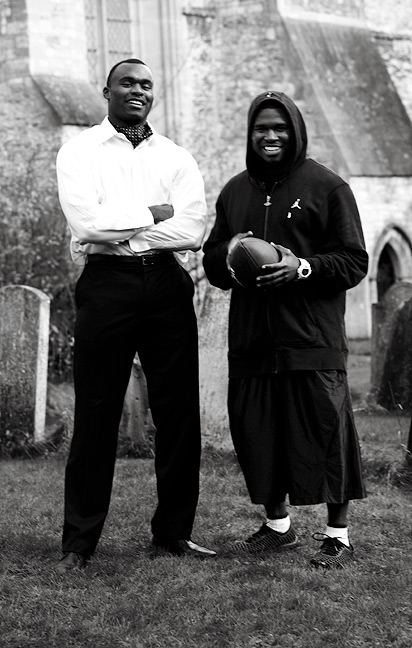

The Rolle brothers park their car -- a Peugeot, a tiny European subcompact -- and, instead of joining the crowd, they head to the rugby pitch and the tiny dungeon of a gym beneath it. Most days, they work out here, alone. When they do use the bigger facilities, the other students gawk at the weight and the reps -- especially the female student-athletes. Rolle and his brother have a code for noticing a young thing sneaking a peek; one will say, with a sly grin: "Mama, there go that man."

This morning, McKinley opens up the binder containing speed guru Tom Shaw's workout and starts counting the reps, converting pounds into kilos. Rolle does leg presses, McKinley a step ahead preparing the next station, the small room echoing with the iPod mix. Except, in place of celebratory anthems, songs about how great today, or this year or his entire life has been, there's a steady stream of rap songs about people being doubted. Rolle sings along -- except when the rappers curse. He skips those words.

Claustrophobic cinderblock walls crowd them. A small window, the spires and castles of the town insignificant through the glass, lets in the only natural light. Rolle comes into focus when he's grinding in the weight room. Outside, the sun is fully up. A song called "Watch Dis" blares through the small speaker. He could lose a step this year, lose some ineffable part of his game that he'll never get back. He knows he risked something coming over here. Knows he still needs to convince people how much football means, and they can't come here, to this room, and see. Rolle lies down on a mat, his feet on a big green medicine ball, his brother taking notes from a nearby weight bench, the Rolle boys, a long, long way from home, counting out crunches in a dungeon, chasing something like that first purple light.

Outside, the chill has come, and, when lifting is finished, Rolle walks onto the wet field under changing leaves, the rugby pitch lined at both ends by a row of tall evergreen trees. They're working on increasing the fluidity of his hips, just one of the many questions about his game. Was he overrated out of high school? Is he too stiff? Does he think too much? Why just one interception in three years? Can he just react and make plays?

McKinley says they got the official e-mail today from the NFL: Myron is invited and will attend the combine. "It was nice to get that confirmation," McKinley says. "He's stronger. Faster. He'll open some eyes."

He urges on his brother through the final rep of the final drill. "Last one," he says. "Last one. Finish strong. First round, baby."

Rolle's face is a portrait of focus. He digs into the field, his cleats kicking up tiny sparks of mud.

Myron, who feels the doubt

The car is cranked, exhaust rising behind them. McKinley is at the wheel, Rolle in the passenger seat. They are ready to go, but Rolle tells his brother not to put it in drive. Not yet. They need the soundtrack first. He punches a button on the CD player, moving through the new Jay-Z album. There's one song he needs to hear right now, three months until February's NFL combine. It's not about good anythings.

"Don't move until we get that track," he says.

"No. 14?" McKinley asks.

"There you go," Rolle says.

As the bass fires up, McKinley pulls back on Iffley Road, headed toward town. The hook comes and Rolle sings along:

"The motivation for me … is them telling me what I could not be.

"Oh, well.

"I'm so ambitious."

Myron, who has secrets, too

About the only time Rolle cusses is for his Mickey Andrews impersonation. He talks real Southern and says "damn sumbitch" a lot. The impression's been on full display all morning; Coach Andrews retired the day before. Two hours ago, at 4 a.m. Tallahassee time, Rolle called. He thought he might get him, but he had to settle for leaving a message, thanking Andrews for all he's done.

When Rolle hung up, he thought about a coach who didn't always understand him but always loved him, thought about one moment in particular, and he found tears in his eyes.

"I needed someone," he says, "and he was there for me."

Can he tell the story?

"I can," he says. "But I have to brace myself. I'll tell it to you in a little bit."

Myron, who is consumed by his goals

Q: Are you chasing what you want or, because you are competitive and driven, are you chasing whatever happens to be society's agreed-upon definition of greatness?

A: Fascinating.

Silence. Then: "I'd say it has part to do with the perceived notion that the Rhodes scholarship, the NFL, are outstanding achievements and agreed upon by the vast majority. To me, it's the highest level of my passions, my individual passions, in academics and in athletics."

When he got here, he found that some people came to Oxford to develop broad intellectual skills that could help change the world and, along the way, to enjoy the experience. Him? He's always been a barrier guy. He's kept a journal of his goals for years, the blueprint of his successes that seem from the outside to just happen. Be a big time recruit. Graduate in three years. Be an All-American. Rhodes Scholar. NFL. In the fifth grade, he read a journal about groundbreaking neurosurgeon Ben Carson, so med school. Be a neurosurgeon. The last page in that journal has two words written on it: First. Round.

Tell me I can't? Watch dis. Cue Track 14. I'm so ambitious.

Myron, who walks past the roses

The square outside the restaurant is filled with arts and crafts, booths selling flowers, people hawking things. Rolle finishes brunch at a breakfast spot he likes; the first time he ordered, the woman didn't believe one person could eat all that food. Now, she grins at him when he steps through the door. Over by a wall, there's an older guy with wild hair. Every college town's got 'em, the wannabe philosopher kings who came and never left. Rolle's carrying a football, and the man sees it.

"Where are you from?" he asks.

"I grew up in New Jersey," Rolle says, "but I played American football in Florida."

"Did you play college?"

"I did," Rolle says, hurry in his voice. "It was a lot of fun. I enjoyed it."

"The best years of my life are school days," the man says.

"I'm having a great time," Rolle says.

"Since I left school," the hippie philosopher says, "I've learned more about life than when I was in school."

"I've heard that," Rolle says.

His voice sounds wistful, or maybe that's the hurry talking. Whatever it is, the time for small talk with strangers is over. He's got an appointment soon, and he doesn't like to make people wait.

Myron, who knows everyone is watching

The students of St. Edmund Hall, wearing traditional academic subfuscs, enter the dining hall for weekly Formal Hall. The lights burn low. The candles flicker. The wine bottles come from their private cellar, and the students find their seats and wait for grace to be said in Latin. The Formal in Formal Hall is no joke. "Mac," Rolle says to his brother, "you remember what you're supposed to do?"

People are always watching Rolle, looking -- hoping? -- to see him slip. He always felt he was held to a different standard; the president of Florida State texted him. Sometimes, he'd see his teammates moving through the world with a carelessness and ease he coveted. As dinner begins, he and his brother joke with their Australian friend Dave Hille about a photo on Rolle's Facebook page. He's posing with two young ladies. It's innocuous, but he's wary.

"A part of me wants to take it down because that's not a good look if a young person sees it," Rolle says. "But a part of me wants to leave it up because I still got it."

This kind of pressure isn't new, either. It's why he doesn't curse when he sings along to music in public. It's why, when he and some teammates recorded a dis track about a fellow Nole to play on a bus to a game, he made sure not to curse there, either … he didn't want it showing up on FoxNews in 20 years. One wrong move and all this -- the Rhodes, the image, the foundation, all of it -- could disappear.

There was a night in college that still gives him chills. It was Halloween, and he and some teammates were at a bar. He doesn't drink, but he still likes to hang out with friends. All around him, drunken students, many wearing skimpy costumes, staggered and swayed. One coed, who he thought was attractive and cool, was dressed like a nurse. She was hammered, so Rolle decided he and his buddy should go home. Only, the girl followed them, got into their car and wouldn't get out. He looked in the back seat and just imagined the Tallahassee cops pulling them over: two big black men and a petite, soon-to-be-passed-out white girl dressed as a slutty nurse. He and his teammate whispered to each other: This isn't a good look.

Rolle phoned her friends, who freaked out, accused him of trying to assault her and threatened to call the cops. His mind raced: I'm like, Are you serious? I'm trying to do the right thing. He saw it all disappearing. They drove around the block, back to the same bar, and got her out of the car. "I would not be here right now," he says. "I shouldn't have even talked to her. I called my brother that night: 'I made a mistake, man.' He said, 'Myron, don't ever do that again.'"

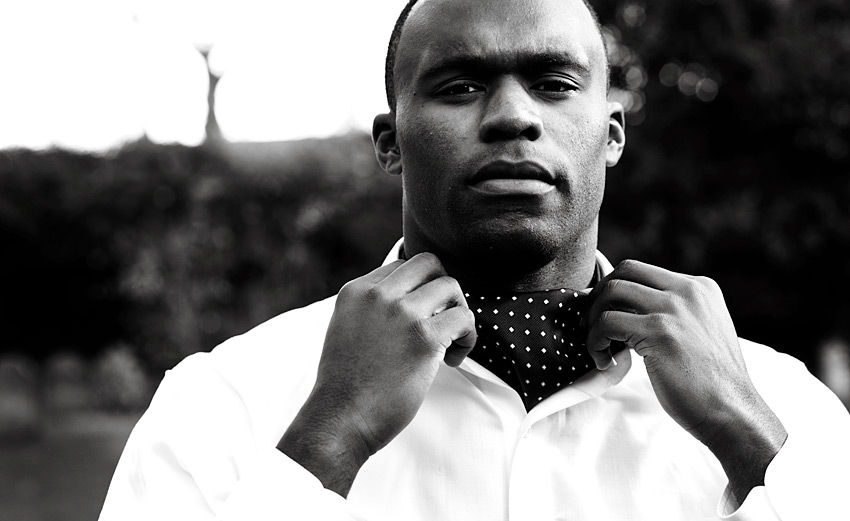

He learned something. No mistakes. Not even one. So he is almost constantly on. When he is interviewed on camera, his vocabulary changes. When he speaks in class, it is not how he speaks in the FSU locker room. Dressing one evening not long ago, he fingered his letter jacket hanging on a chair and asked aloud, "Jock or no jock?" There is the person he is alone, and there is the person he is in front of people. They are not the same.

"He doesn't ever let his guard down," McKinley says.

Each step up, the stakes grow. It's a lot to keep together, through college, through the ancient ritual of Formal Hall, through Oxford, through an NFL career, through a long train of medical school and residency.

And that's just to get to the starting line.

THURSDAY

So what is he like when no one is looking?

Well, walk through the dining room of celebrity chef Jamie Oliver's Oxford restaurant, past the bar, down the spiral staircase, through the ambient candlelight of two more dining rooms, until you come to the last table in the last room, hard against the back wall.

It's Myron Rolle, unplugged; Myron Rolle with his brother and Dave Hille; Myron Rolle the comedian, running through his arsenal of impersonations. He can do Obama. He can -- and often will -- do a dead-on Mickey Andrews, and he imagines Seminoles O-line coach Rick Trickett sitting through one of his Oxford lectures. "Transcendentalism, my ass," Rolle-as-Trickett drawls.

He does SNL skits -- Hey, chicken, say hello to ya mutha for me -- and the unintentionally hilarious speech at the end of "Rocky IV," as comfortable with pop culture as he is with underground Florida hip-hop as he is with Italian opera. Did you know Rolle likes to freestyle rap? He's more than a Windsor knot and an impressive résumé. "People ask what does he do all day?" his brother says. "Study? No, he's carrying on his life. He goes on Facebook. Myron's one of the funniest people I know."

He and the other Rhodes scholars have vastly different life experiences. They're teaching him how to question everything anyone says. Him?

He's teaching them how to talk to girls.

"I'm the Chris Paul around here," Rolle deadpans, passing an imaginary basketball. "I dish. Dish. Dish."

He looks at his brother and grins. A slight clarification is clearly imminent.

"Sometimes I'm Kobe."

McKinley about spits out his food. "Most of the time he's Kobe," he says.

Rolle tells stories about football, about watching Noles make insane plays in practice. One guy leapt a blocker, then stripped the ball. Stunned, Rolle asked afterward: "How did you do that?" The guy's answer? "I just play football." These are the dudes who leave Rolle speechless. They are his boys. They would be on the next flight to Heathrow if someone messed with him. At the last practice before the final Rhodes interview, his teammates gathered around him at practice. They didn't know what exactly he was interviewing for -- some texted him good luck on the "Roads" -- but they knew it mattered to their brother. So they all put a hand on him and everyone said a prayer. "Someone asked me, 'Where do you feel more comfortable, in the locker room at FSU or around the Rhodes scholars?'" he says. "Probably my locker room. We didn't talk about politics or medicine or world health care or world peace. It was just laughing. Here you got to be on your toes. What do you think about Gadhafi's speech to the UN? What do you think about the legislation that was passed in Indonesia?"

Dinner is loose, almost three hours of football and family and girls -- whom the Rolle brothers rate, like, 40 times. She's a 4.4, wind aided. It's one of those meals. The food just keeps coming. Hille cracks on his brother, whose Aussie accent has become stronger since he got to Ohio State for a study abroad. Rolle cracks on Hille for eating so fast, mimicking the call of Bannister's run: "With a new United Kingdom record, Dave Hille consumes his meal."

Mostly, everyone laughs. The night comes to an end, and Rolle sings some '80s hair-band power ballad and women at a nearby table try not to get caught looking.

Mama, there go that man.

FRIDAY

After the talk about Camus' writing on plagues, Rolle leaves the classroom building and crosses the street. Ivy covers the old houses crowding the sidewalk. Tree trunks rise, thick and gnarled. He's going to get a face-to-face critique of a paper he turned in Tuesday. It's on epidemics and endemics, and it's well done, he thinks. He's been so successful for so long that failure is a stranger. Some of his classmates have more firsthand knowledge on the subject -- one of them worked in a refugee camp for Doctors Without Borders -- but Rolle feels confident. How many of them have survived a Bobby Bowden Tuesday practice?

It's chilly out, and he sings quietly to himself:

"The motivation for me …

"… is them telling me what I could not be."

Inside the office, his professor doesn't care that Rolle's a football star, has never heard the words Bobby and Bowden spoken together, isn't concerned with the pressures of being the future of black America.

The paper was not good.

He wants Rolle to do better, and tells him so. Specifically. Repeatedly. When it's over, Rolle's a bit shaken. This has rarely happened to him.

"That was tough," he says. "The last time I got blasted was with Mickey Andrews."

Just like Mickey?

"Less spitting and less profanity," he says.

Rolle dissects the critique. He needs to broaden his understanding of the words "epidemic" and "endemic," needs to think more like an anthropologist and less like a doctor, and he needs to write in a more academic style. He needs to be deeper, smarter.

Isn't this why he's here? To be challenged?

"I don't mind it," he says finally.

He's giving himself a pep talk, on a street in Oxford, and getting better at this paper has become What's Next. The essays aren't graded. That's not it. He wants to be seen as superior, and that means writing papers exactly how the professor wants them written.

"I don't want to be coddled," he reassures himself.

Then: "I love it, though. Challenges make you work."

And finally, convinced: "Let's do it."

Myron, who explains why he talks to himself

Q: Where are the fault lines?

A: How can you see that the pressure is getting to me? I think you can see me pull back more from the community around me. You can see me revert back to the baseline, which is that seclusion, isolation, in my room by myself, internal deep thought and really start to reassess, what's my purpose and should I let other people dictate how I live my life? To be honest, that's what happens whenever there's a failure, or where's there something I don't do well, I always come back to myself: "OK, Myron. You know what you need to do."

Myron, more a smart football player than an athletic student

There is joy on the field today. It's Friday. Another week is almost finished, and Rolle's lifted weights, got a world-class Mama There Go That Man from Harvard sweatshirt, and now he's gonna run some backpedaling drills and call it a day.

"Backpedal and then start sprinting off that," McKinley says. "I'll throw it up."

"What am I playing?" Rolle says. "What coverage?"

"Zone," McKinley says, then barks out a cadence. "Blue 4-2. Blue 4-2. Set, go."

Rolle catches the ball and tosses it back, a huge grin across his face. The little kid inside him comes out, and as he works, Rolle imagines what it will sound like to have his name called. He says it out loud:

"With the 29th pick of the 2010 NFL draft, the New England Patriots select Myron Rolle, safety, Oxford University."

He seems free out here on the field, finding something inside the lines he lacks everywhere else. The game makes sense. The game requires reaction, not obsessing over more academic language. Why does Rolle play football? He might explode without it.

Another rep, another backpedal, another pick. Rolle returns this one and scores an imaginary touchdown. It might be time.

"Prime that thing?" he asks.

Yes, it is time. The Deion Sanders dance, baby. He learned to do this on New Jersey playgrounds at recess, and he bounces from foot to foot, holding the ball high to his chest, in the moment. If potential can be stifling, kinetic is the opposite. He breathes in the crisp air, surrounded by his ancient town. Myron Rolle is on the field and he is happy.

At the end, he holds the pose and smiles.

"Prime that thing," he says.

SATURDAY

The leader of the discussion starts the day of questions with a statement. "The unexamined life is not worth living," he says. "Today our purpose is to address deep issues and examine our all-too-unexamined lives."

The best and brightest eagerly look up from the long table, morning light flooding in through the thick glass of the window panes. All the Rhodes scholars introduce themselves. They are soldiers and astrophysicists, atheists and Muslims, devout Catholics and fervent born-agains, and they are at Oxford because they always seemed to know the answers. Here, they are faced with a different sort of education. They are learning about questions.

Soon, it's Rolle's turn to introduce himself. "I'm Myron, and I'm from Florida," he says, "and I'm doing an MSc in medical anthropology."

Successful businessmen, global lawyers and politicians, many of them graduates of Oxford, sit at the head of the table and subtly direct the conversation. They talk about readings and the philosophy behind them.

There's a passage from "Siddhartha." Everyone discusses the Buddha. There is no reality. There are no individuals. One day, every achievement will be stripped away, and you will be dissociated from your wealth and accomplishments. What does this mean?

Rolle speaks up. "That you can see most clearly when you disengage from yourself?"

The other scholars nod. He breathes in and out, an ocean away from familiar, taking a break in the march toward greatness to ask some questions. What does he want? Are his dreams his own?

They've read Ayn Rand and George Steiner, Bonhoeffer and Eusebius, Martin Luther and John Cotton. "You've been called to be Rhodes scholars because someone believes you can make a difference," they are told. "Someone somewhere believes you can make a difference."

Soon, discussion leaders are peppering the scholars with provocative questions:

"What if you're successful in ways you didn't intend to be successful?"

"Do you need to be raised in a faith to lead a social revolution?"

"Does the Judeo-Christian ethos attempt to make humans be something they should never try to be?"

"This journey, what will you look back on it and see?"

"What will it mean?"

"So many people invested in you. Do you know your purpose?"

"What is your mission?"

And, finally, at the end of the first section: "Where do you get your passion from?"

The discussion has circled around to the central question for Rolle. Is What's Next enough?

The moderators give two options:

1. A burning desire to do something wonderful.

2. A deep righteous anger about a particular injustice.

Rolle murmurs to himself. Soon, the discussion breaks for coffee, and people gather in small clusters in the grand hall, beneath the portraits of Clinton and Mandela, and while Rolle joins in, his mind seems somewhere else. Where does he get his passion? How does this question impact his future?

The group returns to the long table in the room where the light flows through the heavy glass panes. They've moved on, except for one student.

Rolle raises his hand.

He has a final question about the earlier discussion. "What lasts the longest and doesn't fade or wane with time?" Rolle asks. "Which, in your experience, is the most efficient in following your dreams?"

The moderator doesn't hesitate.

The second, he says. The second. What does that mean for Rolle? Every answer at Oxford has a strange way of provoking more questions.

Why does he want to be a doctor? What if a never-ending quest for greatness isn't enough? What if Rolle, whose ability to reach goals has always been rooted in his own internal strengths and desires, has come to a place where hard work alone isn't enough? Is there something crucial that he lacks? Does he need a moment in his past as fuel for the long road spread out before him?

Where would he find such a wellspring of a deep righteous anger?

Myron, who believes he has a destiny

And so now it is time for the story about Mickey Andrews.

Rolle is talking about when he was called to help -- by becoming a doctor, by starting foundations that help obese Native American children, and by opening hospitals in the Bahamas -- when he decided that he was called to ease suffering of people with fewer blessings than him. "We came back full circle," he says. "I don't know if this was the moment that happened, but this was the moment that propelled it to new heights. Coach Andrews."

He exhales hard. A sigh.

"Boy, oh, boy.

"So you wanna hear the story?

"OK.

"So …

"… I am …

"… Hold on a second."

He exhales and looks down. "OK. All right. You can't cry this time."

His freshman year, the Noles were getting ready to play in the Emerald Bowl in San Francisco. One night, he left the hotel and found himself wandering around downtown by himself. Before long, he got hungry, so he stopped in a Denny's five or six blocks from the hotel. An older waitress caught his attention. She looked like someone's grandmother, docile and sweet, and she wore her suffering and sadness as a second skin. She'd been through a lot. He saw that in her face. He saw lots of things in this woman, saw her aura, and maybe a hint of divinity, too.

That's when it happened. Rolle, who was as surprised as anyone, started to cry. He felt her pain as if it were his own. He called his brother and asked, "Why am I feeling this way? I've never felt this way about a stranger. Why am I hurting? Why is my soul hurting?"

His brother's answers didn't satisfy, so he called Andrews. "Coach, I got to talk to you," he said. "Are you in your room?"

"Yeah, Myron, I'm here. What do you need to talk about?"

"It's urgent. I've got to come."

Who knows what Andrews expected? Certainly, when one of his players calls late at night and says it's urgent, they are dealing with something more grounded than an existential meltdown.

"What happened?" Andrews asked when Rolle arrived at his room. "What's wrong?"

Rolle broke down, crying, telling the story between sobs, just a kid, overwhelmed, trying to make sense of his own emotions. His path was already, at that moment, taking him somewhere different from his teammates, and he didn't know what to do. He asked his gruff defensive coordinator: "Can you explain what I'm feeling?"

Andrews didn't blow him off, didn't patronize him, didn't make him feel awkward or foolish. Andrews talked about the Bible, and he told Rolle that he had an uncontrollable love, and that God wanted him to see this woman and feel her pain and be inspired to do something. God, his coach told him, wants you to help her.

Rolle was still crying and Andrews -- gruff, tough, profane Mickey -- gave him a hug. Rolle went back downstairs, different than he'd been before, with a new understanding: He didn't need to know someone to love them, to want to serve them. Feeling the link between two souls who walked different lives, and had different backgrounds, changed him.

To this day, he clings to this story. It's a rudder in the sea of otherwise overwhelming possibilities.

Myron, who says he is self-aware

Q: Would your competitiveness allow you to even know if you no longer wanted to be a doctor?

A: I've done so much to prepare myself for that life, shadowing neurosurgeons, I promise you that if I didn't like it, if I didn't like being in an operating room and studying the brain and the nervous system, if they didn't appeal to me, I can be honest with myself. I can be honest. I can. I'm not so close-minded that I can't open my eyes and see what's happening. Is my interest waning? No.

Myron, who watches the game and misses it

Rolle's body might be in the flat of a professor who knows 13 languages, but his mind, his heart, is on a bus in Florida. He looks at his watch, does the math, and narrates the Seminoles' day.

They're on the bus.

They're at the stadium.

He's there with them, reading the program, getting taped, on the field, watching guys in the cold tub and the hot tub, seeing the dudes lining up early to get wristbands. Equipment managers are stingy with wristbands. He is there with them, missing it, nostalgic, thinking about the season he gave up to come here, and about Bobby Bowden, and about Mrs. Bowden's banana pudding. Mickey Andrews appears on the television screen.

"My man," Rolle says.

Kickoff is near. The band starts playing the fight song, and he gets tense, fired up, game-faced. Tingles. Goose bumps. In the small living room in the flat of the man who knows 13 languages, he looks ready to run through the television and flatten somebody.

"You hear it?

"Ahhhhhhhh."

MONDAY

What's next?

The first light is gone, and it's another week, a week not of distant goals, but of close ones, and Myron Rolle hurries down High Street, a head taller than the other students, and here, on these ancient streets where kings and poets have walked, two blocks from where Clinton studied, two blocks from where Boyle discovered Boyle's law, he begins to sing:

"The motivation for me …

"… is them telling me what I could not be.

"Oh, well."

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com.

Join the conversation about "The Burden of Being Myron Rolle."