A Beautiful Burden

Khadeem Lattin's grandfather and his Texas Western teammates helped changed the course of college basketball. Now the Oklahoma sophomore is continuing the family legacy.

hadeem Lattin opens his eyes, stretches and swings his 6-foot-9 frame out of bed. He smiles, his mind already running through memories of the previous night.

Less than 24 hours earlier, in their last regular-season game on March 7, 2015, Lattin and his Oklahoma teammates beat Big 12 regular-season champion Kansas, finishing their 21-9 season with an exclamation point, thanks to Buddy Hield's tip-in at the buzzer. Lattin, just a freshman, pulled down seven rebounds in 13 minutes for the Sooners, and when Hield hopped on the scorer's table to celebrate, Lattin trailed after him, helping give Hield a triumphant shoulder ride to center court.

Now Lattin reaches for his phone, hoping to rewatch the video of that postgame celebration -- and sure enough, his entire news feed, top to bottom, on Twitter, Instagram and every social media app he checks, is filled with a video starring students from the University of Oklahoma.

Only it's not of Hield or the Sooners' big win.

There will never be a n----- in SAE

There will never be a n----- in SAE

You can hang them from a tree, but they will never sign with me

There will never be a n----- in SAE.

It's a group of Oklahoma fraternity members and their dates, all dressed in formal wear finery, on a bus and singing their own perverted version of "If You're Happy and You Know It." Naturally, someone grabbed a camera phone to record the moment -- and the video immediately went viral. By morning, virtually every news outlet had picked up the story, with even London's Daily Mail referencing the incident.

"It had been such a great day. The game, man, that was awesome, and we were all so happy, and then, boom," Lattin says.

It comes like a gut punch, in an instant replacing the joy he woke up to with a deep, deep sadness. That's the only emotion he feels -- not a speck of anger, just crushing, almost crippling, sadness. Of course, he wonders how people could still think that way -- but he doesn't linger there long, doesn't waste much time trying to answer a question that has been unanswerable for hundreds of years. Instead, he turns his thoughts from the hows and whys of the others to ask a question of himself: What can I do to help?

"It's my responsibility as a person with power on this campus to do something and stand up against injustices," he says now.

And so on a dreary Monday morning, on March 9, 2015, Lattin and 100 fellow athletes gather outside the football stadium, form a circle and hold hands in prayer. They head to the North Oval, uniting with hundreds of others -- football players and ordinary students, teammates and classmates, professors and coaches -- to march in protest. They don't chant or carry posters. They just walk in silence.

Maybe better than anyone at Oklahoma, Lattin understands the power in the simple act of showing up, of being present. Nearly 50 years earlier, his grandfather had changed history by doing just that.

WALKING OFF THE COURT after his middle school AAU team finished its game in Houston, Khadeem saw his grandfather, David Lattin, off to the side. That wasn't unusual. Although Khadeem's parents, Cliff (David's son) and Monica, had divorced years earlier, David, a former college, NBA and ABA player, remained a regular presence in Khadeem's life -- and especially in his basketball life.

David's messages rarely wavered. He taught basketball like he played it, with a direct, unvarnished honesty: Work on the little things. Practice your free throws. Go after every rebound as if it's your last chance. If you're going to foul, by god, make sure your opponent knows he was fouled. Above all else, David stressed the importance of winning.

Khadeem doesn't remember how he played in that particular game. What he does remember is all the people surrounding David, asking for autographs, posing for pictures.

"What's going on? What is this?" Khadeem remembers thinking.

He knew who his grandfather was -- at least sort of. He remembers when, at a young age, he spied David's championship ring and asked him what it was.

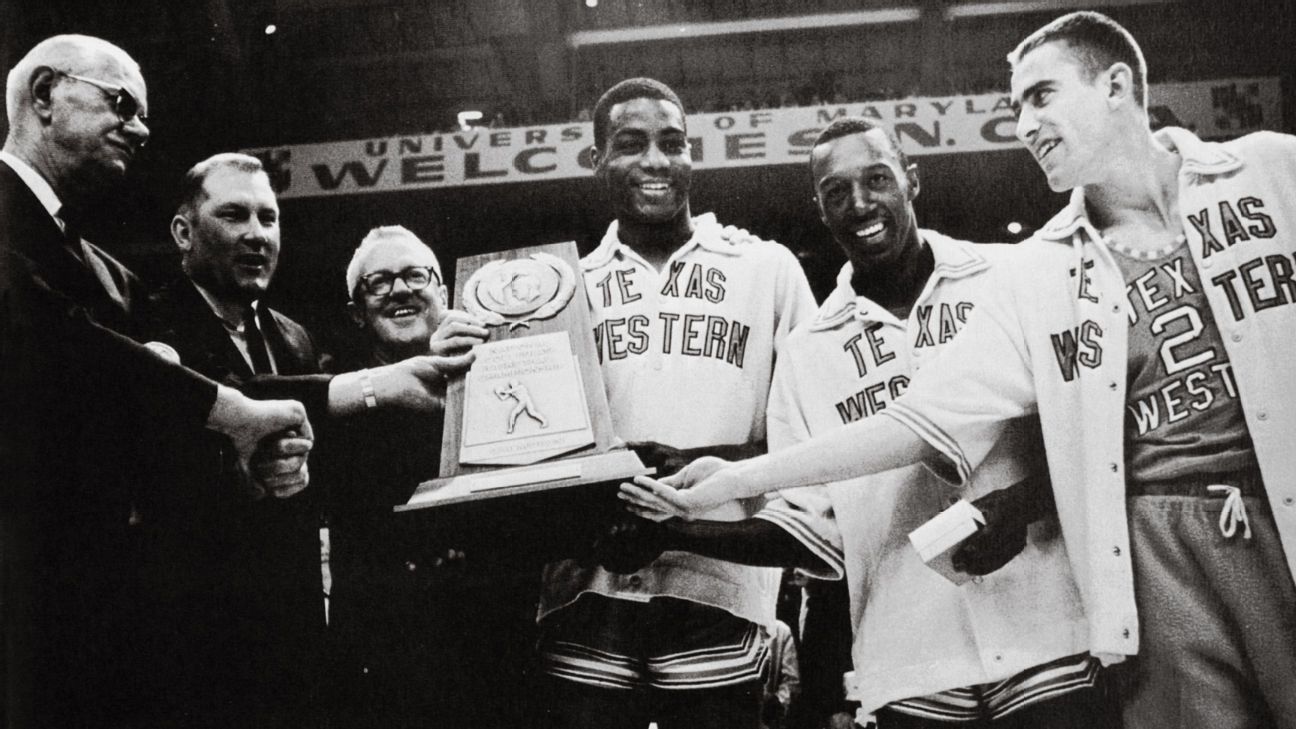

David told him the basics: that he won a national championship in 1966 for Texas Western, that he scored 16 points as they beat the University of Kentucky, that his team's starters were all black, Kentucky's all white.

"And then it was like, Hey, now give me another sip of water," Khadeem recalls. "Like no big deal, so I didn't really make a big deal of it."

What Khadeem didn't understand was that in 1966, the Texas Western basketball team did so much more than win a national championship. The Miners became the first major college team with five starting black players to win a title, beating the all-white roster of still-segregated Kentucky in the process. He didn't know that David "Big Daddy" Lattin's 16 points included the Miners' opening score, a rim-shaking, we-are-here statement of a dunk.

So even though he remembers an elementary school teacher peering at his last name and asking him if he was David's grandson, Khadeem didn't think too much about his grandfather's basketball past -- because his grandfather didn't talk too much about his basketball past.

No wonder, then, that Khadeem didn't understand why all of these people were stopping to talk to his grandfather at this AAU tournament. Turns out it was just before "Glory Road," the movie about Texas Western's 1966 season, was set to debut. David Lattin was never more famous in his hometown.

But to his own grandson, he was still stingy with the details. So when "Glory Road" finally opened in 2006, Khadeem went to the theater. Alone. He didn't want people to ask questions or interrupt his thoughts. He wanted to sit in the dark and absorb the story he could never quite get out of his grandfather.

He saw how the Miners were looked at when they traveled, the death threats coach Don Haskins and his players received. He watched the depiction of that championship game, with the Confederate flags waving in the Cole Field House stands, and he looked at the people -- the fans, the scorekeepers, the officials, the ushers, the cheerleaders, the Kentucky players -- all of them white.

The movie filled in the blanks, answering questions Khadeem never knew to ask. He finally understood why people wanted his grandfather's autograph, appreciated what David Lattin himself was never willing to voice -- and realized why so many have called it the most important basketball game ever played.

"My grandfather really left a major footprint in basketball history," Khadeem says. "That's an awesome thing to say."

Lattin knew who his grandfather was -- at least sort of. David told him the basics, but it wasn't until Lattin saw 2006's "Glory Road" that he understood his grandfather's legacy. Rich Clarkson/NCAA Photos

EVERYONE ELSE HAD exited the bus and headed toward Cole Field House when the white bus driver stopped David, the last to leave.

"'Why don't you just get back on the bus?'" David recalls him saying. "'I'll take you back to the hotel and not even play this game. You'll get embarrassed.'"

David quietly gathered his gear and walked off the bus. He knew the driver wasn't alone in his thinking. No one thought Texas Western had a chance. Kentucky was a powerhouse, already with four national titles to its credit and a head coach, Adolph Rupp, considered a living legend. The Miners, meanwhile -- despite a 27-1 record -- were a largely unknown crew from the dusty streets of West Texas.

This was before television packages and national media coverage made the world a smaller place. The players knew nothing of one another. When David watched the second semifinal, he was stunned that neither Duke nor Kentucky had a black player on its roster. "Dampier, Riley -- they were just names in a box score," he says.

“My grandfather really left a major footprint in basketball history. That's an awesome thing to say.”

- Khadeem Lattin

Most of the teams he'd played against had at least one black player among their starters; he assumed everyone did. But even teams that were "progressive" enough to start one or two black players would never have gone with five. Some white national newspaper writers penned columns on their belief that black players lacked discipline, their style built with flair more than substance.

Texas Western walked into such a cesspool of misinformation and ignorance -- and on the wrong side of the Mason-Dixon line.

It took just one play for the Miners to make their presence known, to Kentucky and most everyone else. On the Miners' second possession of the game, David took a pass from teammate Bobby Joe Hill and slammed a thunderous dunk.

"Pat Riley [a junior starter on Kentucky] made the statement once that he had no idea what they were getting into," David says. "He said that they were fighting for just a trophy and that we were fighting for something else -- for everything, to prove that we could play on that level and African-American players could beat anybody."

Change was coming, and even without the Miners' triumph, David says, integration was around the corner. In 1963, University of Houston coach Guy Lewis told David that, although he desperately wanted the hometown star on his roster, the university "wasn't ready" for him. Months before Texas Western's victory, running back Warren McVea made his debut for Houston as the first black player at a major Texas football program.

Texas Western's charge wasn't so much to promote change but to make sure the Miners didn't impede it by losing the game.

"It would have been terrible [to lose]," David says, "because everything would have gone backwards. Everything that everybody had been working for would have gone backwards. ... I can't imagine what it would have been like if we had been defeated. We almost had to win."

"Glory Road" depicts a thriller, a game that comes down to the final second. In reality, the Miners won with ease, beating Kentucky 72-65 with the kind of solid defense they'd used all season. After they won, after the celebration and the trophy presentation, David walked back to the bus, wordlessly passing by the same driver.

"I looked at him, and he took my bag and put it on the bus," David says. "There was nothing else said."

Lattin went to Spain as a 15-year-old to become a better basketball player. He came home a better person. AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki

A CONTINENT IN MINIATURE: 60 KM OF BEACHES.

That's how HelloCanaryIslands.com bills Gran Canaria Island, the third largest of the Canary Islands, a Spanish archipelago off the coast of northwestern Africa.

Khadeem Lattin will have to take the tourism folks' word for it. He lived in Las Palmas, Gran Canaria's capital, for nearly two years in high school. But while cruise ships came and went in the popular port, Khadeem feasted on a daily dose of hoops at the Canarias Basketball Academy, a basketball-centric boarding school.

"It was definitely kind of militant," Lattin says of the regimented schedule. The "optional" workouts, he says, were never optional. "But I needed that at the time."

He was an immature 15-year-old, he says, a little less focused academically than he could have been and in need of a greater understanding of what it means to work hard.

The Canarias Academy was Khadeem's mother's idea, and not an altogether popular one. Monica Lamb-Powell starred at USC and the University of Houston and helped the Houston Comets to three straight WNBA titles from 1998 to 2000, but she also spent a good deal of her pro career overseas. Lamb-Powell loved the way Europeans played ball, and even more how they taught it. Instead of pigeonholing kids early based on their size, she saw a model that taught the same fundamentals to everyone.

As Khadeem grew, nearing the 6-9 height and 7-2 wingspan he would reach, she knew his destiny -- a traditional back-to-the-basket post position -- and she didn't like it. She wanted her son's skills, not his physical attributes, to dictate his position. So she made a few phone calls, reached out to friends and colleagues overseas, and learned of Canarias.

The academy essentially exists so European players can catch the eye of U.S. coaches and, hopefully, earn a Division I scholarship. Lamb-Powell was proposing sending an American to Spain, which, frankly, made no sense. In a sport in which most foreign players are desperate to show their talents in the United States, she wanted Khadeem -- a player already climbing up the national recruiting rankings -- to take his talents to Spain.

More than a few people in Houston -- including David Lattin and John Lucas, a former NBA player and coach and Khadeem's one-time trainer -- didn't agree with the plan. Still today, David passes it off as "[Khadeem's] mother's idea." Even Khadeem wasn't too sure about it, until his AAU team spent 21 days touring and playing in Italy. He fell in love with Europe -- the cultures and the people, the food and the basketball.

When he came home, he reconsidered his mother's offer, imagined what it might be like to actually live in Europe and challenge himself as an athlete and as a person. He was young but already introspective enough to recognize that he needed to mature. Although he was admittedly scared and more than a little overwhelmed, Khadeem agreed to the move.

“I'm really lucky just because I didn't do anything to deserve a grandfather that did what my grandfather did.”

- Khadeem Lattin

By then, her initial idea close to a reality, Lamb-Powell was every bit as nervous as her son. She knew the extrovert would be fine socially, joking she could drop him in any country and he'd find new best friends in an hour. But she also knew she was asking a lot of a 15-year-old, so she gave him an out, packing him off with an undated return ticket, his passport and enough money to get him to the airport.

"I told him, 'Whatever the reason -- you don't even have to have a reason -- just go and call me and tell me when to pick you up,'" Lamb-Powell says. "This is the only time in life you'll get that kind of carte blanche from me."

He never used it. Not that it was easy. The schedule was brutal and the basketball intimidating. He was the only American student in his age group at the entire academy. He bunked with three other students -- one from Israel, one from Slovakia and one from England. Mercifully, they all spoke English -- everyone on the team did -- but not everyone spoke American basketball.

Khadeem remembers practices when he would naturally dunk a ball and everyone else would stare -- most other big men, even the 7-footers, would dunk maybe once in practice. Or he'd make a mistake, something silly, and they'd point to his head, writing him off as another stupid American with a game based more on athleticism than intellect.

Still he refused to go home too soon, and so he stayed for a season and a half.

"I couldn't quit," he says. "I couldn't bail. It was a really big experiment, so I couldn't risk for it to fail. I knew I had to dive in."

Did the experiment work? In terms of pure basketball, maybe not. Lattin fell off the recruiting grid in the time he was gone and had to reintroduce himself to college coaches. Of course, a 7-2 wingspan can make up for a temporary disappearing act, and eventually he had a host of suitors, fielding offers from Alabama, Arizona, Baylor, Georgetown, Texas, Texas A&M and TCU before opting for Oklahoma.

Although coach Lon Kruger believes Lattin is only now beginning to scratch the surface of his talent, he's essentially a traditional post player, just as he might have become had he stayed in the states. But to Lattin, it's inaccurate to judge the move purely on basketball.

"You don't learn a lot until you're thrown in the fire," he says. "I was really thrown into the fire."

He went to Spain immature and insecure and a little goofy. He came home with his playfulness still intact but smarter and worldlier, confident that he could stand on his own, and certain of who he was becoming.

His mother saw the benefits immediately and still sees them today as Khadeem matures into the person he wants to become.

"It's not unlike his legacy with David and the expectations that come with that," Lamb-Powell says. "My advice to him always is, 'It's a marathon, not a sprint.' Do not play outside yourself. Play your role, but also find joy in that. Don't do it in suffering. Find contentment.

"Every opportunity in our life can teach us lessons. I know he wants to stand on his own, to create his own legacy. This is all part of creating that."

Because of his grandfather, Khadeem Lattin has a voice that has power. UTEP Athletics

AFTER A PRACTICE last month, a fan handed Lattin a gift, a program from a recent game at the University of Texas at El Paso, once known as Texas Western. He hadn't even left the court before he started flipping through the pages.

On Feb. 6, the school celebrated the 50th anniversary of its 1966 champions, and the commemorative program included loads of stories about that team. David Lattin attended the tribute, alongside seven of his teammates, including Nevil Shed, Willie Cager, Willie Worsley and Orsten Artis. The pregame celebration included a number of video presentations, and a halftime ceremony included a video tribute from President Barack Obama.

"They didn't know it at the time, but their contribution to civil rights was as important as any other," Obama said. "That's what we honor today: a group of Americans who laced up their shoes and moved our country forward."

That contribution also moved Khadeem Lattin to march on that dreary morning last year. The act was a protest, but he wasn't motivated by anger. He felt sad yet hopeful that maybe by being there, by using his clout, he could promote change and healing.

And the protests worked: The fraternity's national office announced it was closing the OU chapter, and the university expelled two members. Later, the fraternity house was repurposed for office space, including some designated for the Southwest Center for Human Relations, a group that promotes understanding among people of different backgrounds.

Khadeem Lattin easily could have shrunk from his grandfather's legacy. After all, how do you blaze your own trail when a true trailblazer is in your own family? When you are born with a significant surname, how can you become significant in your own right?

"A beautiful burden" -- that's what Khadeem calls being a Lattin. Marching on that day, Khadeem believes, was the first step in easing it, in moving to his ultimate goal -- making a difference on the court and off, just as his grandfather did 50 years ago.

"Right now, I'm known as his grandson," he says. "I want him to be known as my grandfather."

David still texts him after nearly every Oklahoma game, including that triple-overtime loss to then-No. 1 Kansas this past January, in which Khadeem missed a free throw in the final seconds of regulation. (The only words from his grandfather? "Work on your free throws.") He has followed Oklahoma's season -- in which the Sooners have been ranked as high as No. 1 in the country and lost just two games to unranked teams -- as closely as anyone. He beams when he speaks of his grandson, averaging 5.3 rebounds and a Big 12-leading 2.1 blocks per game, saying he believes Khadeem is already a better basketball player than he was at the same age.

And of course, he has a suggestion for his grandson to cement his own legacy: "Khadeem just has to win a national championship."

This year, the Final Four is in Houston, the Lattins' hometown. David and the Texas Western team will be honored that weekend. Oklahoma's win in the West regional final means Khadeem will be there, too.

Only not as a spectator. Since this season began, he has been consumed by the same thought -- of mirroring his grandfather's national title with one of his own. Khadeem is only a sophomore, and there will be other chances at a title, but perhaps none better than this one.

Not just because the Sooners are loaded -- and they are: Hield is a player of the year favorite, and the Sooners' offense seems to be peaking at the right time in this tournament -- but because the timing is just right.

"I think about it. I dream about it. I hope about it and I pray about it," Lattin says. "Fifty years. It's perfect."