Activism in the NBA

LeBron's outrage, Melo's truth, and Thabo's quest for justice: A three-pack of our best stories on NBA players speaking out.

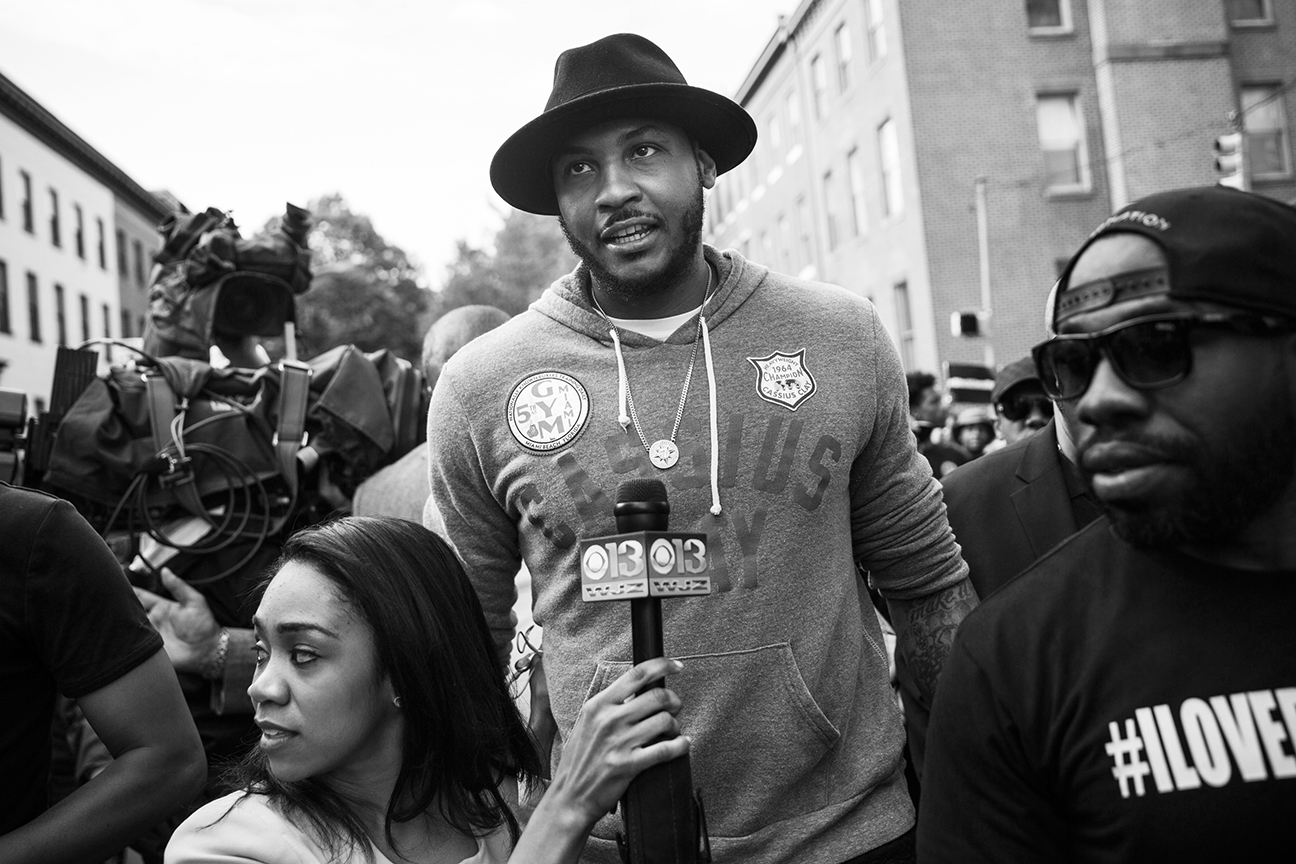

The Truth According To Carmelo Anthony

On the cusp of an NBA season that will give rise to the next wave of athlete activism, Carmelo Anthony reveals how he found his voice and power.

A collaboration with the Undefeated. This story was originally published on Oct. 18, 2016.

In a normal time, it would be implausible to sit down with Carmelo Anthony two weeks before the start of the NBA season and not talk about basketball-to not hear a word about his Knicks, his Olympic gold in Rio or his new All-Star teammates. But this isn't just any time in America. Since the early summer, when six police officers were acquitted in Anthony's hometown of Baltimore after facing charges resulting from the April 2015 death of Freddie Gray, basketball for the Knicks' franchise player has become secondary to being an active, involved citizen, one aware of his power and influence-and often the limitations of each. We spent a recent afternoon together in New York talking as black citizens and parents, debating race and policing, owners and players, and the increasing politicization of sports in a tense, post-Ferguson nation. For Anthony, there is no more holding back.

HOWARD BRYANT: It sounds like there's a sort of tipping point that's happening around the country. When I talk to younger people, they have this attitude like, "We're supposed to be past this. This is why I'm upset." And then I talk to my uncles and they're like, "See, this is how it is. This is nothing new."

CARMELO ANTHONY: This is the new '60s right here. Everybody I talk to, my mom and uncles and friends, they say the same thing. They're like, "What you're seeing right now, we'd seen it already. It's new to you, but it's not new to us." I think it's bigger and much deeper than just actually seeing what's happening out there. Not just police brutality but so many other issues out there that are being swept under the rug. Our educational system is messed up. Schools are closing left and right.

HB: What you're touching on is the one part of this that's been really difficult for me and people wanting to talk about Colin Kaepernick. They're not focusing on why he's doing what he's doing. They look at Baltimore and they're not looking at the fabric of Baltimore. You have no parks. You've got no infrastructure. What do you expect that to look like if you're taking all the resources out of the community?

CA: When you don't have resources, it becomes hopeless. There's nothing to look forward to. I know when I was coming up, it was after-school. We had rec centers to go to in our neighborhoods. We had parks to go play in. We had football fields to go to. You had different things that you could go do. I always find it fascinating when I go back to my community and kids that I have known, or their parents, just hearing them talk. The one thing I get out of it is they just want a voice. They just want to be heard. It's like, "We want everybody to hear us."

HB: When you talk about this, you're not really talking about police brutality specifically. You keep saying, "The system is broken."

CA: The system is broken. It trickles down. It's the education. You've got to be educated to know how to deal with police. The police have to be educated on how to deal with people. The system has to put the right police in the right situations. Like, you can't put white police in the ‘hood. You just can't do that. They don't know how to react. They don't know how to respond to those different situations. They've never been around that, you know? When I was growing up, we knew police by their first name. We gave them the nicknames. But that's only because we related. And when the white police came into our neighborhood, the black police said, "Yo, we got this." That doesn't happen anymore. You got black police afraid to go into black communities now, and the white police are like, "Shit, I'll come. It's a job. I'll go in there and do it." Not knowing what's going to happen.

I think athletes now are just going off of what they're seeing now, which is what? Police brutality. Police killing people. You haven't seen one thing about schools closing. There's no rec centers. You haven't seen none of that on the news. All you see is police killing people. And if I'm sitting there watching that every day all day, I'm going to feel a certain kind of way. Like, against the police. If it was showing schools and why they shut them down and there's no funding for this and no funding for that, you would feel a certain way about that too. But that's not what they're putting out there.

HB: The thing that bothers me most about this is that people believe, especially about black athletes and black professionals in general, "Well, you made it. What's the problem?" They seem to treat you as if having success forfeits your voice, when actually it should empower your voice.

CA: The reason I feel so strongly about my beliefs is that it's been going on forever. Then a part of me is like, "I can't speak up on every single issue because then it'd be like, 'Oh, he's just talking again.'"

But when it's powerful, timing is everything, and for me the Freddie Gray thing was the one that tipped me off. It was like something just exploded. It was like [snaps] now was the time. Enough is enough. And everybody's calling me like, "We should do this" or "We should do that," and I was like, "I'm going home." If you want to come with me, you come with me, but I'm going home. I'm not calling reporters and getting on the news; I'm actually going there. I wanted to feel that. I wanted to feel that pain. I wanted to feel that tension.

HB: I remember when I was in college at Temple, just walking down the street. Here come some cops, put me on the ground at gunpoint. When that happens, it can't be any more personal.

CA: When you're in that environment, it's a part of your life. You can't control it. And it's not until you step outside of that environment and start looking back that you're like, "Oh, this is messed up." I sit down with different people I grew up with and start reminiscing, and before when I used to tell that story it was, you know, funny. "Yo, remember when we got pulled over? When the police put us on the ground or they chased us?" It was funny. Now that shit ain't funny no more.

HB: Did you watch the Tulsa video? [Ed.'s note: The Sept. 16 shooting, captured by a police officer's dashboard camera, showed an unarmed black man, Terence Crutcher, being shot and killed by a white cop during a traffic stop. The officer, Betty Shelby, has pleaded not guilty to first-degree manslaughter.]

CA: Yeah, of course.

HB: I watched that and the first thing I said was, "That's a murder." That was the first thing that hit me.

CA: Right, and you could watch that with kids, and even kids will say that. There's no more hiding news.

HB: Yet you still have a lot of people who just don't see that this is an issue.

CA: Everybody knows it's an issue. But it's deeper than that. It's higher than that. The system is broken. And we'll continue to keep saying that. How can you sit and watch an execution live? And now it's starting to become a norm to watch that. When you see it now, it's like, "Oh, man. Another one got killed. Another guy got shot." And you know, just like in anything, not all police are bad. You know what I mean? You have good ballplayers, you have bad ballplayers. You have good writers, you have bad writers. You have good drummers, bad drummers.

HB: You've met with law enforcement. What has the response been?

CA: Speaking to them directly, you realize you are very limited in what you can do. I've met with a lot of them, all over the country, and they get it. They understand, like, you know, it's messed up. They're like, "We don't condone that."

HB: But …

CA: "But at the end of the day, we roll with the blue." Like, "We're the boys in blue, and we stick by our code." And I don't want to sound crazy when I say it's understandable, because if something happened to somebody on my team, they get in a fight, you're going to protect them. And from that perspective you understand it, but you realize that what you can do has limitations.

And I realize that they're scared. When you're going out here every day, when you're putting that uniform on, in certain neighborhoods you don't know what's going to happen. But that's because there's a distrust.

HB: The dynamic in sports, the NHL aside, is white owners, white media, white coaches, black players. That dynamic makes it difficult to be understood. How do you feel like your message has been received?

CA: I control my own message. I don't go through the traditional outlets to get my message out there. I create what I want to and I put it out there on my own.

HB: Whatever gestures you decide to make this season in support of your message, as a team or individually, what do you expect the reaction to be?

CA: The NBA is very supportive. They want to team up with us and be behind it, but at the end of the day it's still a corporation, so there's only so far that they're going to let you go. And one gesture's not going to change anything. So regardless of if we stand out there and put our arms around each other to show unity and solidarity, on the flip side, at the moment somebody goes out there and puts their fist up, that's going to be something different.

Colin Kaepernick sat down. That caused a different reaction. And people didn't even know why he was doing it. They just thought it was disrespectful to the actual soldiers and people who fought for the country, and it had nothing to do with that.

HB: Have you spoken to Colin at all? What was your initial reaction when you saw it?

CA: I spoke to him that night. He reached out to me that night. And I'm watching and I'm like, "OK." Like, "What's next?" In a very respectful way, he was like, "I took this step and, you know, just wanted to get your thoughts on what's happening." And I said, "Well, you're courageous." I said, "You just showed a lot of courage in what you just did, but now is the hard part because you have to keep it going. So if that was just a one-time thing, then you're fucked. But now you keep it going and be articulate and elaborate on why you're doing it, and be educated and knowledgeable of why you're doing it so when people ask, you can stand up for what you believe in and really let them hear why."

HB: You're talking about issues that most of America doesn't really want to talk about, yet you also just played for your country and won a gold medal. How does being called unpatriotic affect you?

CA: I mean, you hear it. I just think that's bullshit for somebody to call me unpatriotic. That's totally bullshit. I've committed to this country on many different levels. Committing to USA Basketball since I was 19 years old, playing in four Olympics, going to the different parts of the world. Where they were warring, you know? Traveling to Turkey where they were bombing the building three doors down from us. Going to the games where they've got "Down with the USA" signs out there.

You're representing something that's bigger than yourself, bigger than the New York Knicks or any other team. You're representing the whole country. You've got the USA on your chest, and when you hear that national anthem, regardless of how you feel about it, you get a sensation inside you. That's why the emotions came out after the fact, because I knew what was going on back here in the country, in our own communities. And for me to know that and still be over there fighting and playing and representing our country on the highest scale that you can represent it in sports, it was all those kind of emotions.

HB: In the NBA, it seems like you have more power-more than NFL players, more than some baseball players. I always thought that standing up in 2014 during the Donald Sterling thing was a real opportunity for players to say-

CA: I said the same thing. But I never stepped out there and said anything about the Donald Sterling piece because at the end of the day, you realized that it's bigger than you. It's like police brutality with the system. The system is broken. It's a bigger entity than you are. Right? So you're dealing with something much more powerful that kind of controls you in every sense that you can imagine. The way I would have done it if it was close to me is I wouldn't have come out. That was the opportunity right there: "I'm not playing." At that point it wouldn't have been about basketball at all. That was a race issue right there. That was where you could have put your foot down and said, "No, we're not-we're not having it."

HB: Don Yee, Tom Brady‘s agent, said players have no idea how much power they've got, that they could bring this entire system down and create something for themselves if they wanted to. If I just move over into just the system of sports, is there something different and something better to be made?

CA: I think the resources are there. I think we're powerful enough. I can only speak for basketball players. We're powerful enough to, if we wanted to, create our own league. But everybody would have to be willing to do that. You have to be willing to say, "This is what I'm going to do. I'm supporting this right here." Because at the end of the day, the athletes are the league. Without the athletes, there's no league. Without us, there's no them. And they don't think like that. They say, "We're your main source of income, so you're going to need me before I need you." I think you just have to be willing to do that. You have to be willing to make that move, and, you know, strength comes in numbers. If you don't have those numbers, it's not going to work.

The people in the position of power understand now more than ever that some of the athletes are just as powerful as them. And that's the scary part. To know that, "Somebody I'm paying, you know, is just as powerful as me. We don't want that."

HB: I make the argument that in the 21st century, the black athlete is the most influential black professional in the United States. There is a history, a heritage of outspokenness. Yet through about 30 years, the mid-'70s up until the late '90s, you didn't really hear a lot. So people seem surprised when they hear you talking now.

CA: It was about building that corporation. And it was about building the perfect athlete. Michael Jordan came in, and he transcended the game to another level on the court and off the court. So everybody wanted that typical athlete, that clean-cut athlete suit. Politically correct. Never spoke outside of his message. When you had athletes who spoke out during that era that you're talking about, the ones that did speak out got ousted. It was, "Put the muzzle on your face."

HB: It's the evolution of the athlete. Now it's athlete as an individual corporation. But the difference is you have every other ethnicity out there, they get to be proud of what they are. You hear in media, so many writers going, "Well, and I don't want to be a black writer. I just want to be a writer." And I'm like, "Well, why don't you get to be both?"

CA: Because it's not accepted. We're the only culture, we're the only race that doesn't have our own. For us, what we have? We have the ‘hood. So there's no resources in the ‘hood, other than drugs. Either you have a good jump shot or you selling crack rock. These other races out there, they got their own neighborhoods. They got their own community, their own stores. They support one another. And we don't.

HB: And where does that come from? That comes from the fact that we have separated education from community. My neighborhood in Dorchester, in Boston, in Roxbury-any black family that had any prospects, they left. Why? For the schools.

CA: Because there's no resources.

HB: And when stability's gone, what's left?

CA: Nothing. Hopelessness.

HB: Yet you hear this cognitive dissonance when Baltimore hits and people say, "Why are they burning down their own neighborhoods?" without realizing they aren't ours.

CA: That's right. We don't own anything. That Rite Aid? That isn't ours. And that's what I'm talking about when I say it's all part of something bigger. These times, they're crazy. It's not about the one thing. The system is broken. You hear people saying, "Justice or else." I think you're starting to see what "or else" looks like.

Illustrations by Oliver Barrett

More From The Undefeated

More From The Undefeated

The Undefeated is the premier platform for exploring the intersections of race, sports and culture. Not conventional. Never boring. Undefeated home »

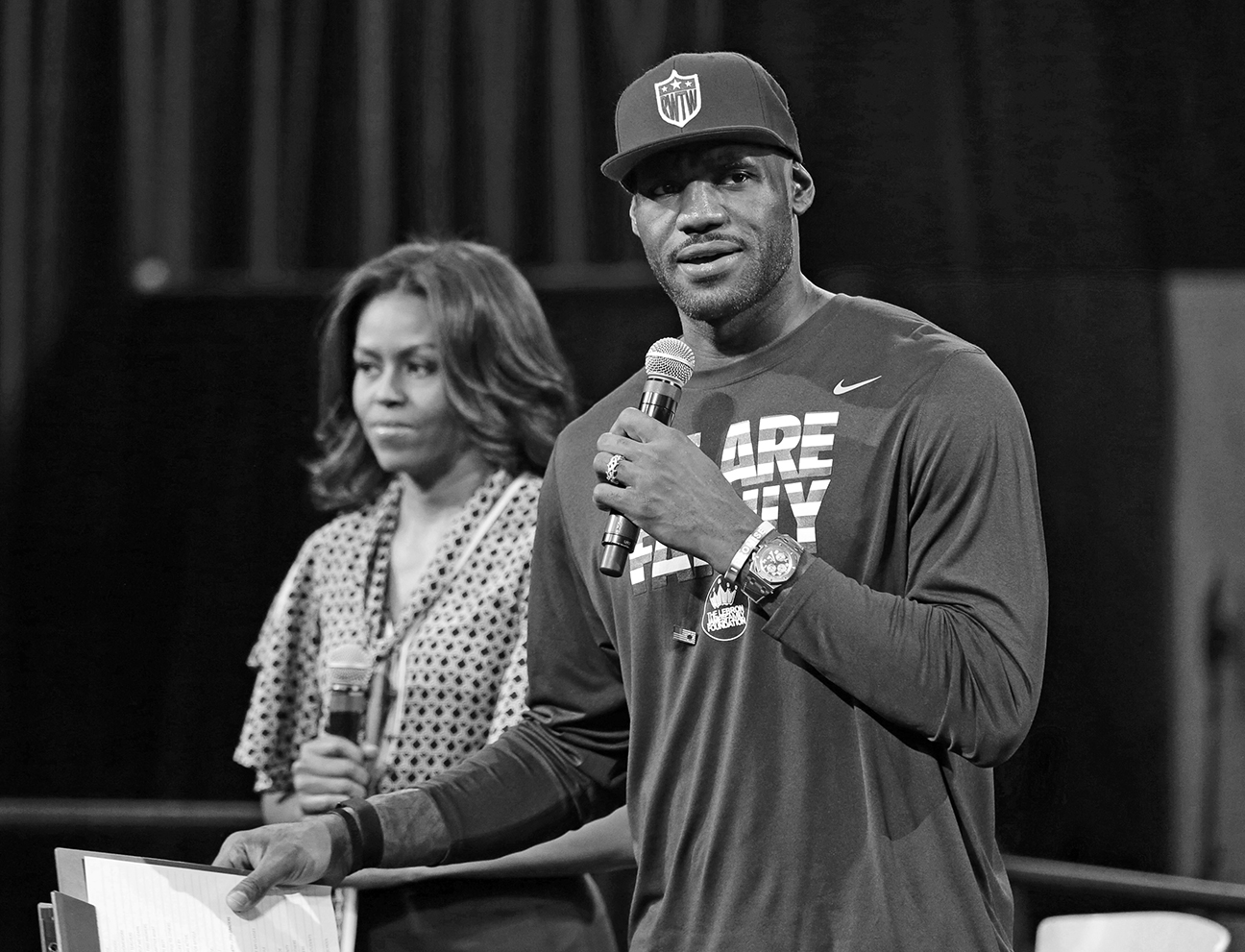

Waiting For Lebron

LeBron James' outraged response to the horrific shooting of an infant in Cleveland suggested the game's biggest star might become its loudest activist. And then he went silent. Why?

This story was originally published on May 3, 2016.

Charles Wakefield buckled his 5-month-old daughter, Aavielle, into his Oldsmobile, tightened the straps on her new car seat and double-checked the infant safety locks.

His girlfriend climbed into the driver's seat, and Charles kissed her goodbye before stepping back from the car. "Be safe," he told her, because that was what he always said, even though his girlfriend, mother and daughter were driving just four blocks to Save-A-Lot to shop for his birthday cake. Tomorrow he would turn 38.

It was the first day of October and also nearly the beginning of the NBA season -- his favorite time of the year. The Cavaliers had long been his preferred distraction from the blight of East Cleveland, and this year he coveted escape more than ever. The past month had been the city's most violent in recent history, with 19 people shot dead, including several shootings near Charles' house. He had grieved for three friends and two neighborhood toddlers caught in deadly crossfire, and each time he had pushed Aavielle in her stroller to their memorials.

"Mini-me," he called her, because she had his dark eyes, his rounded cheeks and his throaty laugh, and because she went with him everywhere during the day while her mother worked. Charles had already bought her a LeBron James T-shirt to match his own.

Charles walked back toward the apartment where he lived with his girlfriend and Aavielle, but his cellphone rang before he could reach the door. It was his mother, who had promised to call from Save-A-Lot to give him a choice of frostings. "Tell me they got the buttercream," Charles said as soon as he answered the phone, but on the other end he heard muffled screams. "What is it?" he asked, and now he thought he could make out sirens and hysterical sobs. "What? What?" he shouted.

"It's the baby," his mother said, finally. "She got shot."

During a terrible year of gun violence and racial tension in Cleveland, in a historically bad month, Charles began sprinting from his apartment toward the city's latest crime scene. There, in the fading daylight of rush hour, was his Oldsmobile, riddled with bullets because shooters had mistaken it for a different car. There, sprawled out on the hood, was Aavielle. One of the bullets had pierced the edge of her plastic car seat, hitting her in the side. Charles' mother had lifted her onto the hood to administer CPR, and with each chest compression blood trickled out from the baby's nose. "Oh god!" Charles screamed, and he thought he saw Aavielle lift her eyes at the familiar sound of his voice. But when he picked her up, she was limp in his arms.

He cradled her at the crime scene, at the hospital and then for a long while after doctors said there was nothing more they could do. Her skin started to gray. Blood soaked into her sweater. Charles asked doctors to bring more blankets so he could continue to hold her, and as he rocked his daughter at the hospital, the leaders of a city inured to gun violence began repeating Aavielle's age on the nightly news and grieving not only for her but for what Cleveland had become.

"When are we going to stop counting babies being killed in our streets for nothing?" police chief Calvin Williams said that night. "This pervasive violence is crippling us at our core," said Marcia Fudge, a U.S. congresswoman.

In those first few hours on Oct. 1, one voice in Cleveland resonated loudest of all. LeBron James was the one person in the city who remained equally popular with politicians, big corporations and residents on the Lower East Side. For more than a decade, he had moderated his political voice, usually speaking in universalities, but on this night he heard about Aavielle and reacted on social media with raw indignation.

"Like seriously man!!!!" he wrote on Twitter to his 23 million followers. "A baby shot in the chest in Cleveland. It's been out of control but it's really OOC. Ya'll need to chill the F out."

Then, three minutes later: "C'mon man. Let's do and be better! This can't be the only way."

JAMES HAD BEEN watching TV on the couch in his living room when he first saw pictures of Charles' anguished face come across the news feed on his phone. James' own children, ages 11, 8 and 1, roamed the family's 19-room estate on Idlebrook Drive. Their house was set on 7 acres in the hills between Akron and Cleveland, less than an hour from Charles' apartment, protected by 24-hour security, steel gates and a series of guardhouses scattered across the property. It was the safest place in the state.

But James had grown up in subsidized housing in a part of Akron that was much like East Cleveland, hollowed out by foreclosures, disappearing jobs and rising crime. He had started a foundation aimed at providing college scholarships for more than 1,000 children in those neighborhoods, and now his own daughter, Zhuri, was just months older than Aavielle. His reaction to her death was that of a father and fellow citizen -- guttural and immediate.

"I know what I see. I know how I feel," he said the next day to the press corps that awaited him after practice, asking about his tweets. "Obviously you're not going to be able to take every gun out, but if there's some big-time penalties or rules or regulations, people will second-guess themselves."

In a career mostly spent avoiding controversy, this was perhaps James' most unfiltered comment, and his closest observers wondered whether it might be a sign of more to come. For a decade, James had been trying to find his cultural voice, torn not only by his responsibilities to corporate sponsors that paid him $44 million each year but also by a contradiction within himself. He loved and admired the apolitical business instincts of his idol, Michael Jordan, whom James once referenced when he said in 2008: "You want to keep athletics and politics separate." But he also admired the courage and "authenticity" of his other idol, Muhammad Ali, and wanted the freedom to "speak openly on the issues I care about," he said in 2014.

Split like this, James cushioned his social criticism in generalities and cautious gestures. He had hosted a rally for Barack Obama in 2008, but before endorsing the candidate, James had spoken about the universal importance of voter registration. He had posed in a hoodie for Trayvon Martin -- but surrounded himself with his Miami Heat teammates. He had worn an "I Can't Breathe" shirt to protest police brutality -- but only after a few other NBA players had done so first. When asked about the country's growing racial discord in 2014 and 2015, he said things like: "We have to grow together and not apart." Or: "I'm not pointing the blame at anybody." Or: "Society has come a long way, but it just shows how much further we still have to go."

The difference between James and every other athlete was that because of his basketball dominance and global fame, even his careful activism had the ability to drive the news cycle -- a responsibility he seemed ready to embrace when he announced he'd come back to Cleveland in 2014. "My calling here goes above basketball," he wrote then.

And now here came one of those opportunities to lead, on gun violence in Cleveland, which had experienced an 18 percent jump in homicides and a 31 percent increase in assaults with a firearm that year. Instead of going halfway, this time James had been unequivocal: "There's no room for guns," he said, during that same news conference after Aavielle's death.

Afterward, gun control groups thanked him -- while gun rights groups called him a hypocrite and posted photos of him firing a machine gun at a shooting range. Activists encouraged him to push for policy reform. Four days after Aavielle's death, the Cavs followed James' example and invited Charles and his family to a team scrimmage. The Cavs offered Charles box seats and gave him a tour of the court and then the locker room, where he had been hoping to meet James. He stood outside and waited, but a locker room attendant came out to apologize. James had an NBA season to prepare for, a commercial to film -- so many audiences to please.

"I wanted to thank him and see if we could keep pushing the issue," Charles said, but he didn't blame James for not meeting him or read too much into it. "People are paying attention because of LeBron," Charles said. "He's trying to make sure we get some justice and see this city change."

A few weeks later, the Cavs opened their season in Chicago, and when James walked onto the court, there was Obama, seated with the Secret Service in the front row. The president had made gun control a priority in his final year in office, and he had come to think of James as not just a great basketball player but a possible ally -- an athlete who was potentially willing to break the mold of "just be quiet and get your endorsements and don't make any waves," Obama said.

"We forget the role that Muhammad Ali, Arthur Ashe and Bill Russell played in raising consciousness," Obama once said. And now came a season of unrest in America in which James would have the rare opportunity to add his name to that list, if only he could first resolve the conflict within himself. Jordan or Ali? Athlete or activist?

Could he not only provide Cleveland with a distraction from its problems but help solve some of them?

"Good luck," Obama told him, as James ran onto the court.

CHARLES WATCHED THE same game on TV from his new bed, a sloping couch in the living room of his mother's rental apartment in East Cleveland, where he'd been living for the past few weeks. Aavielle had been dead for a month, and so much about his life had begun to unravel. His girlfriend, Aavielle's mom, had left him because of her own grief. He had been out of work for a year and couldn't find a job in a neighborhood with high unemployment. He had no working car, no money and no choice but to live off his mother's disability check in an apartment two blocks from where his daughter had been shot.

Charles turned on the game and watched in the living room with his mother. The team blew an early lead. LeBron had a last-second layup blocked by Pau Gasol. "The Cavs lose," the announcer said.

Charles had been a devoted Cavs fan since he was a teenager, back when he was a good high school player himself, but now he was so desperate for the predictable simplicity of a game that he rewatched each broadcast several times in the night. The investigation into Aavielle's shooting had stalled without any leads, even though the prosecutor had offered a $25,000 reward. James had yet to mention the shooting again, and Charles' gratefulness for James' public reaction was now tinged by the fact that he wished James would say more. Each time the replay of the game ended, Charles had nothing to do but lie on the couch and think, and his mind always went back to the same awful night.

Now the game started again on TV. Charles sat up on the couch. "The Cavs lose," the announcer said.

For several weeks, Charles had been afraid to go to bed. He took naps, but whenever he tried going to sleep for the night, bad dreams followed. His nightmares played out to a soundtrack of the frantic 911 calls he had heard witnesses making from the scene of the shooting. Charles had gotten tapes of the calls, hoping he would hear the final sounds of his daughter's voice. But instead, each call was more hysterical than the last, until even the seasoned 911 operator began to lose her composure. "A baby? It's a baby baby?" she had said in disbelief.

Charles turned up the volume for another broadcast, and by now he could remember each possession. The sound of dribbling echoed in the living room.

"How should we respond?" some of his friends had asked that first night, assuming Charles would retaliate, but instead he handed out fliers asking for leads and passed a good tip on to investigators. He researched how to make steel-plated car seats and how to improve the city's 911 response times. He took over a Facebook page called "Put the Guns Down Movement" and began remodeling himself as (an activist, emailing politicians and organizing rallies.

He continued to hold out hope that maybe James would join him and say something more about Aavielle or about guns. "We can't just keep moving on and turning away and hope the problem gets better," he said. "We have to do something."

Now it was 8 a.m., and the sun was coming up. One more replay. One more chance for distraction as he watched James run across the screen.

TO BE THE Chosen One in the instant-media moment of 2016 meant that every action birthed a chain reaction, which for James had become both a benefit and a burden. He once expressed an interest in acting, and suddenly he had TV shows on two networks and a prominent role in a Hollywood comedy. He tweeted a request for new music at Kendrick Lamar, so Lamar released an entire album early to fulfill his request. He spoke for a few minutes about the shooting of a 5-month-old girl, and protesters traveled from around the state to line the streets of East Cleveland for rallies and marches, many of them wearing James' No. 23 jersey.

But the spotlight also meant that James' most banal actions could lead to unease. He laughed with opponent Dwyane Wade during pregame warm-ups in Miami and his bosses questioned his loyalty. He unfollowed the Cavs on Twitter and fans wondered whether he was preparing to leave Cleveland for another team again.

Sometimes it seemed as if the scrutiny could make him withdraw. As the season wore on, he entered into what he called his "Zero Dark 23 mode," limiting social media and barricading himself in a corner of the locker room with headphones, because, he said, "I don't need nothing creeping into my mind that don't need to be there." (James declined to comment for this story.) For LeBron, basketball had always come first, in part because his play on the court earned him his power. So instead of talking more about guns or social issues in Cleveland, James chose to stay silent, and whether out of a single-minded focus or cautious self-regulation, he refused to comment late in the year when asked about the presidential race, the upcoming Republican National Convention in Cleveland and even the biggest story in the city: the tragic death of Tamir Rice.

The 12-year-old boy had been shot by a white rookie police officer while holding a toy gun late in 2014, and a year later a grand jury declined to indict the officer. By late December and early January, the case had become national news. Cleveland verged on the same racial discontent that had manifested in Ferguson and Baltimore, where standoffs between police officers and thousands of protesters shut down the streets.

It was James' potential Ali moment, some activists said -- a chance to make a controversial stand and step firmly into the social and political space. Rice's mother asked for LeBron's help publicizing the case. A group of organizers from Black Lives Matter created a plan to spur him into action. They started a campaign asking him to sit out games in protest of the grand jury's decision.

"You are who you are because of your habit of rising to the occasion," wrote Tariq Toure, the activist who started the movement, in a direct letter to James. "This is an occasion that comes along every 50 years."

On Martin Luther King Day, protesters planned a vigil at the entrance to Quicken Loans Arena. "No Justice, No LeBron," they shouted. But meanwhile, inside, James took the court to play against the Warriors. He had never considered sitting out and had chosen not to speak much about Rice, saying only: "To be honest, I haven't really been on top of this issue, so it's hard for me to comment." It was time for basketball, after all, for Zero Dark 23 and nothing else, but on this day, James seemed as uncertain on the court as he did of his own social activism. The Cavs trailed by 15 in the first quarter, 30 in the second and 43 early in the fourth in what would be the worst home loss of James' 13-year career.

In a city where his influence was unrivaled, on a day when some asked for him to make the biggest stand of his career, he was still attempting to go halfway. Nike designed him a special pair of shoes. The sneakers were made to honor Martin Luther King Jr. and Black History Month. Nike had stitched a special message on the shoe that spoke not only to the power of a movement but also to James' unique influence.

"The Power of One," the message read, and it was stitched to the sole of the sneaker, where no one could see it.

WITH A MONTH left in the regular season, Charles splurged on a trip to his first Cavs game of the year. He drove by his old apartment and turned onto the street where his daughter had been shot, before continuing downtown to the arena, where he found a seat in the upper deck.

James was sitting down too, resting for the night to prepare for the playoffs. Charles had tried to send James a few messages in recent months about Aavielle and gun violence on his public Facebook page, but he hadn't heard back and didn't expect to. What he felt for James now, watching him recline on the bench in a T-shirt, was both a kinship and a sense of remove that seemed much farther than the view from the upper deck. "He did so much, but ultimately this is my life and my problem and he has other responsibilities," Charles said, and then he tried to lose himself for a few minutes in the game.

The music made him think of Aavielle. The birthday announcements on the scoreboard reminded him that her first birthday was just weeks away. "It's like I can't take being alone and then I can't take being with people," Charles said, and by the time the Cavs beat the Mavericks 99-98, he was happy to be headed back to his car.

He drove home, where on this night there was news waiting. The Cleveland Police Department had called to say it had made an arrest. The high publicity of the case had resulted in a tip that led to a suspect. And it wasn't the villain Charles had first envisioned but a neighbor -- a 30-year-old man who lived down the block. Charles had barbecued with him. They had watched Cavs games together. If Charles had expected a wave of joy or satisfaction or even relief, this wasn't it. His daughter was still dead. His neighborhood was still a mess. Cleveland was still divided by race and poverty and violence in a year when not enough had changed.

"Does anybody really have the power to change all of this?" he asked, thinking about James, realizing the difficulty of his choice, the impossibility of it even, the athlete and the activist.

He sank back down on the couch and turned to the distraction he always sought, his own version of Zero Dark 23. He put on the TV and began watching the first replay of the game.

Illustrations by Oliver Barrett

More From Doubletruck

More From Doubletruck

Doubletruck is the home for ESPN storytelling, a space to find great features, investigations and character portraits. Doubletruck home »

The Prosecution of Thabo Sefolosha

On an April night in New York City, the Hawks forward was injured and arrested by the NYPD. This is the exclusive story of how, in the aftermath, he became what he never wanted to be: a civil rights symbol.

This story first appeared in 2015. Thabo Sefolosha has since filed a lawsuit against New York and five NYC police officers.

Five minutes and 22 seconds after Thabo Sefolosha came out onto the sidewalk from a Manhattan nightclub on the morning of April 8, his wrists were manacled behind his back and two policemen were steering him by his elbows toward the rear seat of a cop car.

In the days, weeks and months to follow, Sefolosha, a Swiss native of South African descent and a key player for the Atlanta Hawks, would retell the story of those five minutes over and over again -- to his lawyer, his wife, his parents, his coaches, his teammates, the media, the jury, himself. In his memory, it doesn't seem like five minutes. It doesn't seem to him anymore like a space of time at all. It's as if those five minutes won't ever end. "There has honestly not been a day I haven't thought about that night since it happened," he says. "There's no escaping from it."

The team's plane had landed in New York around 1:30 a.m. for a game against the Brooklyn Nets. Earlier that night, in Atlanta, Sefolosha had played 20 minutes against the Phoenix Suns in the nastiest, most belligerent game of the season. There were seven technical fouls. A Suns player was ejected. Now, at the Ritz-Carlton hotel in lower Manhattan, where the team was staying, Sefolosha didn't feel like sleeping; he was too amped up. When he'd talked recently over the phone to his brother in Switzerland, he'd told him he was excited for the playoffs, which were starting in 10 days. He'd been to the NBA Finals once before, with the Thunder three years earlier, losing in five games to the Heat. Now, playing off the bench for the Hawks, who had clinched the top seed in the Eastern Conference, he wanted another chance at a title. He was a month from turning 31, old for the NBA. Who knew how many more opportunities he'd have. "Man, I've never felt like this," he said to his brother. "We have a real shot. I'm going to give it all I got. I'm going to be a locomotive."

A friend of Sefolosha's, a sports agent living in New York who represents other NBA players, had texted, suggesting they meet at a place called 1 Oak in the city's Chelsea neighborhood. Sefolosha had heard of the club -- the kind of high-end, velvet-rope establishment that paparazzi encamp outside of in hopes of DiCaprio sightings -- but he'd never been there. Sefolosha's friend and teammate, Pero Antic, decided to go along. The club was becoming packed. They took a VIP table. At such tables, the only choice is to buy full bottles of liquor. They ordered one of Jameson and one of vodka. Sefolosha mixed his Jameson with Sprite; he had two or three of these. They got to talking with other clubgoers, whom they urged to pour themselves drinks from the bottles; there was no way Antic and Sefolosha could finish them. An hour passed. His friend the agent rose to say good night, and not long after he left, the house lights came blazing on and the music died. Everyone had to go, the bouncers said, giving no reason, and they all went, exiting orderly through the front door.

Emerging onto the street, they could see to the left what appeared to be a crime scene. Dome lights rotated atop police cars and emergency vehicles. There was a length of yellow tape and many uniformed cops shouting Clear the block! Everyone was being herded to the right, away from the yellow tape, down 17th Street toward its intersection with 10th Avenue, about 40 yards west of 1 Oak. Despite the cops' instructions, people were coming out of the club and mingling in little groups on the sidewalk and in the traffic-blocked street, including Antic and Sefolosha, as can be seen in CCTV surveillance videos. People they'd met at their table were wishing them well in the playoffs. Someone said, "Bonne chance." Sefolosha found himself talking to two women he'd met at the table that night, one of whom, he'd learned, had dated a current Hawk.

Now Sefolosha and Antic registered one cop in particular. He had a high-and-tight Marine Corps haircut. He was 5-foot-7. He was, according to witnesses, shouting: "Get the f--- off my street."

"Get the f--- off my street," the cop said again.

Antic is a bald 6-11 Macedonian, close to 300 pounds, with a dense black beard and a voice like a contrabassoon. A friend once described him as "resembling Xerxes," the ancient Persian warlord. He tends to stand out in a crowd. Yet the cop seemed now to be focused solely on Sefolosha, according to the court testimony of a 1 Oak bouncer and that of the two women Sefolosha had met at the club. Standing 6-7 and wiry to the point of fatlessness, with a triangular face accentuated by a faint goatee, Sefolosha was wearing black jeans and a black hoodie. He wore the hood up. Sefolosha now said to the cop something along the lines of: "Relax, man. We're going." He and his group reached 10th Avenue. Many things were now happening at once. There was a livery cab, a black SUV, parked on 10th right at the corner. The driver asked whether anyone needed a ride. Sefolosha said yes. At one point Antic had wandered off from Sefolosha, but now here he was again, saying he'd found out that Chris Copeland, the Indiana Pacers forward, had just been stabbed. Outside the club! That's what the crime scene back there was for! Could Sefolosha believe it? And now, according to trial witnesses, the one cop seemed to be in a rage. He'd told them to move; why were they still lingering? Get the f--- out of here. Sefolosha said something back. He recalls lines of dialogue, largely corroborated by other witnesses. "You can talk to people nicely, it works just as well." And: "It's because you have a badge that you're a tough guy."

"With or without a badge," the cop replied, "I'll f--- you up." (Much later, when the officer was asked under cross-examination whether he had uttered these lines, he said, "I do not recall.")

Sefolosha did not back down. "C'mon, man. You're 5-foot-2. You're a midget, man. Relax. I guess I'd be mad too if I were a midget."

The cop seemed to move away. Other officers were urging Sefolosha and Antic to get into the SUV, to leave immediately. One cop, by his own account, was even holding its door open. Sefolosha muttered that he didn't understand why he was being chased off so aggressively -- many others were milling around at that same moment -- and he couldn't resist another crack. "I pay my taxes," he said. "Matter of fact, they probably pay your salary." Then, just before he was about to duck into the SUV's back seat, a man approached.

"Yo, you gonna help a brother out?"

Sefolosha recognized him from earlier, when he and Antic first walked through 1 Oak's ropes. He seemed to be a panhandler who worked the area. Sefolosha had refused the man's earlier entreaty, but now he peeled a twenty from his billfold. According to Sefolosha, he made a point of saying out loud: "I'm going to give this guy some money." He never got the chance. As can be seen on the CCTV video of the scene, the cop at the door of the SUV took the man by the arm and ushered him away. Irritated, intent now on pressing the bill into the man's hand, Sefolosha took a few long, swift steps toward the pair, trying to catch up. But before he could get there, someone checked him in the side, spun him around and took him by the right arm. Sefolosha recalls the cop saying, "That's it. You're going to jail." And then there was another cop, and then another: They were flocking to him. They had him by both arms. He dropped the $20 bill to the ground. "Relax," Sefolosha said, addressing the cops. "Relax." He was resigned now to being arrested. Running through his mind was: Get to the police station, clear up this misunderstanding -- and get back to the hotel before anyone's the wiser. This is not a good look. And then he felt a kick to his right leg and a flash of pain, and then his left side rose into the air as if lifted up by someone, and then he was falling and then he was on the ground, his face against the pavement, the knees of officers pinning him there.

FOUR MONTHS EARLIER, when the Hawks played in New York in December 2014, Sefolosha and his wife, Bertille, were in a taxi that had come to a halt in midtown Manhattan. Traffic was at a standstill, and people were marching by with signs that read black lives matter. It was a mass protest in response to a grand jury's decision not to indict the NYPD officer whose chokehold had killed Eric Garner four and a half months earlier. Sefolosha and his wife got out of the cab and went into the crowd. He took photos and the next day posted one on Twitter. "It was good to be in NY and see people getting there [sic] voice heard by protesting in the streets," Sefolosha wrote in a tweet. He ended it with a hashtag: #icouldbenext.

The New York City Police Department has a contentious history of allegations of misconduct -- enough of one that there's a heated Wikipedia page dedicated to the subject. In the past 15 years, the city has paid out on behalf of its police more than $1.2 billion in settlements and judgments. In 2014 and 2015 alone, it paid $318.4 million in settlements. By way of comparison, Los Angeles paid $74.4 million over those same two years. Adjusting for population, NYC paid almost twice as much per person.

New York's problem also appears to be growing. From 2000 to 2013, the NYPD averaged payouts of $64.4 million per year; the past two years, that figure has risen to $159.2 million, almost 2.5 times as much. New York City's Civilian Complaint Review Board, an independent watchdog agency that investigates grievances by citizens against the police, also reported that in the first half of 2015, 49 percent of the alleged victims in CCRB complaints were black; NYC's black population stands at 26 percent. That ratio conforms to national averages. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, from 2002 to 2011, black people were 2.5 times more likely than white people to have experienced nonfatal force in their most recent contact with police and 1.7 times more likely than Hispanics.

THE 10TH PRECINCT, on 20th Street in Chelsea, is a vintage New York City police station. It could have been an interior in a scene from Serpico. It was the setting for the 1948 noir classic The Naked City. Sefolosha and Antic were now inside it. Antic had been arrested too. As the cops had been yanking on Sefolosha's arms, an alarmed Antic says he tapped one of them on the shoulder to ask what was going on. He was shoved onto the ground and, after Sefolosha was subdued, himself taken into custody. At the precinct, the pair sat handcuffed to a bar running along a wall in a corner of the big, open central room. More than two hours went by, according to Sefolosha, before they were allowed to make their first phone call -- to Andre Cottle, then the Hawks' head of security, a former Daytona Beach vice cop beloved by the players.

"Andre. I'm in jail," Sefolosha said.

Cottle thought he was joking. "What? Stop playin'."

Some of the cops who'd tackled and arrested Sefolosha were all now at the precinct, their shifts evidently close to ending. After Antic and Sefolosha were fingerprinted, after they'd answered name-age-occupation types of questions, it must have become clear to the officers, if they hadn't known it already, that these were two NBA players. They did not, to Sefolosha, appear in any way unsettled by this fact. He remembers one of them saying to him: "Hey, when you get out of here, maybe we can play some one-on-one." Sefolosha's ankle throbbed and had begun to swell, but he refused an offer to go to an emergency room. "I wasn't about to go to a New York hospital in my handcuffs as a criminal," he says. "I might still be there." He preferred to see the Hawks' world-class doctors. Before he could do that, though, he and Antic needed a lawyer.

About 7 a.m., one showed up. He wore a suit and carried a briefcase but looked disquietingly young. His name was Alex Spiro, 32 years old, a protégé and partner of legendary New York criminal defense attorney Benjamin Brafman (former counselor for John Gotti). Spiro was acquaintances with Scott Wilkinson, executive VP and chief legal officer for the Hawks, which is how he got the phone call in the first place. Spiro's résumé: Harvard Law, a stint with the CIA and five years as an assistant district attorney in Manhattan covering this very part of the city. He personally knew many of the officers based out of the 10th Precinct, especially among the detectives, with whom he had worked closely as a prosecutor bringing cases. (He is also one of the few lawyers in the city to have prosecuted a police officer for misconduct and, after switching sides and joining Brafman, defended one against charges of criminal misconduct.) Spiro had reason to believe his new clients had a small chance of walking away that day without being charged with any crimes. According to Spiro, one of the detectives who'd been tasked with investigating the Copeland stabbing had announced to him, "This is a bulls--- arrest."

But a dismissal wasn't to be. Several hours later, at the courthouse, Sefolosha was arraigned on charges of disorderly conduct, resisting arrest and obstructing governmental administration in the second degree (which means he was being accused of interfering with the Copeland crime scene). Antic was also arraigned on an obstruction charge, with additional counts of disorderly conduct and harassment (of a police officer) in the second degree. All were misdemeanors but, if the players were convicted of them, could lead to jail time.

Even before they were transferred from the precinct to the court, news media had gathered outside. If you Googled his name in the following weeks, the first image you saw was Thabo Sefolosha in a black hoodie and handcuffs being perp-walked out of the precinct.

AT THE END of a Ritz-Carlton corridor was the hotel room of Mike Budenholzer, the Hawks' head coach. He'd summoned Sefolosha and Antic shortly after they'd finally arrived back at the hotel from the courthouse in the late afternoon. The coach's room awaited them like a confessional.

Sefolosha felt both guilty and innocent. He was acutely aware of how it all looked. He had been out on a school night at 4 in the morning at a famous late-night party emporium. He'd spent the past nine hours incarcerated. He was now accused of crimes. It was all over the news, and many initial reports had conflated his and Antic's arrests with the Copeland stabbing -- were Sefolosha and Antic somehow involved in that? "There's no point in sugarcoating anything," Sefolosha said to himself and then to Antic out loud. They knocked on the door.

Budenholzer was stone-faced as he took in the details. But as the story went on, his eyebrows climbed. "They described to me everything that happened, including some things they could have done different, or they could have been more perfect at," Budenholzer now says. "They were very honest. But what happened to them, in their minds, was not right. And as I put it all together, I felt the same way."

He told his players to go back to their rooms, take a shower: "You guys are not playing tonight. We'll figure it out. Get some rest."

"But Coach, that's not all, man," Sefolosha said. He'd waited until the end to disclose the ugliest upshot: the extent of the pain he was then feeling in his ankle. He believed he'd suffered a serious injury. He needed to see the team doctors.

"That was tough, telling him that," Sefolosha says now. "That's when I really felt like: F---, I'm letting the team down."

Budenholzer acknowledged that this turn of events was not ideal. But he says he never doubted that his players had been arrested unjustly. Budenholzer told Sefolosha at one point, "This is what's wrong with America."

BUDENHOLZER WAS THE first to inform Sefolosha that a video of his encounter with the NYPD, shot on a cellphone, had appeared online, published by TMZ. A day later, a second video, shot from the opposite angle, went up. In the video, Sefolosha, surrounded by cops, is being pulled and pushed this way and that before what looks like five officers tackle him to the ground. A woman's alarmed voice is saying, "They didn't do anything!" and "Stop!" The voice belongs to one of the women who'd met Sefolosha and Antic inside 1 Oak. She shot the video. Her friend, who also had met the players that night, can be heard on the video saying, "He was trying to give him money." Most memorable, though, is Sefolosha's own voice. In the beginning of the video, he's still upright but caught at the center of a scrum of cops. His position is precarious, volatile -- you can tell that, very soon, he'll be going down hard -- and it's right at this point that he says to the cops, in a futile effort to reverse the inevitable: "Relax. Relax."

That evening, in the locker room before the game with the Nets, Budenholzer made a few brief remarks to the team on the events of the morning and Sefolosha's injury. He didn't dwell on it. But over the next few days, as they watched the TMZ videos and as a fuller understanding of what had happened spread among the players, many of them grew angry: angry on behalf of Sefolosha, angry that yet another episode of what appeared to them to be racially motivated police violence had touched one of their own, and angry that an incident having nothing to do with basketball had sidelined a key player, damaging the potency of their team as the playoffs loomed. Says Hawks guard Kyle Korver, "Nothing upsets me more than people who abuse their power -- and the police are people with power." For some black players, Sefolosha's experience renewed a kind of but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I feeling.

"We understand you have to be careful, even in situations where you're not even doing anything wrong," says one. Darvin Ham, a Hawks assistant coach who played eight years in the NBA, says, "Every time you have an interaction with a police officer, it's always in the back of your mind as a black man: They may come at me aggressive. It's unfortunate, but I have to have that talk with my sons. 'Be polite, talk to them with direct eye contact, make sure they see your hands.' "

For the Hawks in April, all of these feelings had to be put aside. Still, as the playoffs were set to begin, a few of them reached out to Spiro to run an idea by him -- a show of solidarity for their fallen comrade. Spiro considered it, but he ultimately counseled the players against it, concerned it might impair his efforts to get Antic and Sefolosha cleared. Before a game in December, LeBron James, Kyrie Irving and the Brooklyn Nets had famously worn T-shirts that said I CAN'T BREATHE -- the words Eric Garner had uttered while a cop choked him to death. The Hawks players had also wanted to don black T-shirts during warm-ups before a game. Across the front, the shirts would have said: RELAX.

BERTILLE SEFOLOSHA MET her future husband in 2002 in the French town of Chalon-sur-Saône, in Burgundy. It was where she'd grown up, the daughter of a Cameroonian mother and French father. Thabo Sefolosha had moved there from Switzerland at 18 to play on the junior squad of the town's pro basketball club, Elan Chalon, and to study at a local lycée. They were essentially high school sweethearts. When Bertille heard the news that her husband had been arrested outside a nightclub at 4 in the morning, and likely injured, she says her mind was filled only with worry -- for his health, his career.

Only later, once he was sitting across from her at the kitchen table of their large house in Atlanta's Buckhead neighborhood, where they live with their two daughters, 6 and 7 years old, did her thoughts turn probative, incredulous, suspicious. She has long brown hair that she wears in braids, skin that looks almost golden, a master's degree in international relations and the cast of mind of an investigator. She grilled her husband at that table. "I asked him like a million questions," she says. How long were you at the club? What time were you first approached by the police? Who was the taxi driver there? Did she see what happened? The homeless guy -- why did you insist on giving him money? Why didn't you just get in the car and go? What exactly did you say to the police? But you must have said something!

Pero Antic came by the house a little while later. She sat him down and grilled him too.

Bertille says she wasn't doubting her husband's story; she was playing prosecutor, trying to prepare him for the road to come. But after he answered her many queries, Sefolosha's mind cycled. "I was like: Is that really it? Am I missing part of it? I was doubting myself, I was questioning myself." Sefolosha's concerns were later confirmed -- his right fibula had indeed been fractured, the ligaments shredded around the ankle and at the top of his foot. And in a cast after the surgery, his ankle ached. He struggled to sleep. He lost his appetite. He began having weird abstract nightmares that left him not with memories of the dreams' narratives but a vague sense of dread.

AN UNCERTAIN SUMMER

All through the spring and summer, Sefolosha and Antic waited. Meanwhile, the playoffs unspooled without Sefolosha. He watched impotently as the Hawks advanced to the Eastern Conference finals, only to be swept by the Cavaliers and James, who averaged 30.3 points, 11 rebounds and 9.3 assists in the series. Sefolosha -- with his 95.3 defensive rating, third among all NBA small forwards with at least 40 games played -- would have been tasked with guarding James. As he does every year, Sefolosha took his family home to Europe for July and August. Antic went back to Macedonia; his contract with the Hawks ended and he struck a deal to play the next season at Fenerbahce, a pro team in Istanbul.

There were many within the Hawks organization and in the players' union who believed that the Manhattan District Attorney's Office, responsible for investigating Sefolosha and Antic for the misdemeanor counts against them, would at some point drop the cases. It seemed absurd to them that it had even gotten this far. Hawks execs felt the holdup almost assuredly had to do with the inevitable civil lawsuit Sefolosha would file against New York City and the NYPD for breaking his leg and endangering his career. (Despite his strategic disclaimers in the media, Sefolosha knew almost from the start that he would sue, but only after the criminal case was resolved.) If the DA dismissed the charges, it would only strengthen Sefolosha's civil lawsuit. On the other hand, if the government took the case to trial and lost, that too would arguably boost the strength of Sefolosha's suit.

In late July, Spiro met with supervisory prosecutors in the DA's office and gave a presentation that revealed CCTV footage (along with the TMZ videos) of the altercation and moments surrounding it. He applied the law to the facts. He attempted to demonstrate that reasonable doubt loomed large behind each of the counts against his clients. He reiterated that under no circumstances would his clients take a plea. Still, the prosecutors were mum. Another month passed. Early on in the process, a tentative trial date of Sept. 9 had been set. That day arrived, and all the parties convened at 100 Centre St., the city's downtown criminal courthouse, so bleak and inhospitable it's almost Gothic. The charges against Antic were dismissed in full but not those against Sefolosha.

For him, the DA's office had another offer: one day of community service and something called an adjournment in contemplation of dismissal, or ACD. If accepted, this meant that the charges against him would be expunged from his record in six months. An ACD, in other words, is essentially a dismissal, albeit a delayed one. For somewhat complicated reasons, ACDs are now standard operating procedure for prosecutors in New York state when they want to resolve a case without trial. A person inside the Manhattan DA's office says that when it comes to any kind of altercation with police, a complete dismissal "just doesn't happen." Indeed, Antic's full non-ACD dismissal was highly rare, offered only to the incontrovertibly innocent, such as in clear-cut cases of mistaken identity. An ACD is actually only slightly less rare. According to a recent study, the DA's office chooses to prosecute 96 percent of the misdemeanor cases brought to it by the NYPD.

In New York City, few (if any) of the defendants accused of the same crimes as Sefolosha have the resources of an NBA millionaire. Many don't have the money even to make bail. Thus, despite sometimes dubious charges and weak cases against them, defendants accept plea bargains just so they can get off Rikers Island. "These types of cases are a joke among public defenders and prosecutors," says one Legal Aid attorney. "It's often police arresting someone because they didn't show the expected deference to police authority."

In many ways, then, the deal offered to Sefolosha was a good one. For two weeks in September, he pondered the decision: take the ACD and move on with his life -- he wouldn't even need to appear in court again, and his fingerprint records would be destroyed -- or fight the charges at trial. At first, the latter option seemed lunatic. To do so would be to risk a jury's conviction, which in turn could lead to all kinds of nasty outcomes, including deportation (he had no green card) or the termination of his Hawks contract. Even prison time wouldn't be off the table; Spiro informed Sefolosha that the max sentence would be two years behind bars. "The practical man takes this deal," Spiro says.

When Michele Roberts, director of the National Basketball Players Association, first heard that the Manhattan DA's office was not fully dismissing the charges against Sefolosha, she says she was "absolutely shocked ... and then I was angry." Roberts, a former Washington, D.C., lawyer, has won cases for defendants she showed were victims of excessive police force and has successfully defended cops being prosecuted for excessive use of force. Says Roberts, who had sent the union's general counsel to the precinct on the morning of April 8: "It was a quote-unquote generous offer, but that's the offer you make when you know your case is weak. And if you're acknowledging in any regard that your case is weak, dismiss it!"

Again and again, Spiro and Sefolosha weighed the pros and cons. But the more Sefolosha considered it, the more he wondered. Taking the ACD, to him, carried a certain residue, almost as though he'd be copping to a kind of figurative guilt. By accepting it, he'd be conceding that his arrest had been lawful, that the police had been within their rights to take him into custody -- which could undermine his civil suit. Conceding it also meant that he could never show what he believed to be true: that he'd not deserved to have his leg broken by a scrum of cops. It was, in a way, perverse. It was clear to Sefolosha that if his leg had not wound up broken, if he'd been uninjured just as Antic was, his case too would have been fully dismissed.

As Spiro and Sefolosha were going over all this, some news hit the wires. Earlier that very day, Sept. 9, possibly while Sefolosha was standing next to his lawyer in criminal court, a white NYPD detective had tackled and handcuffed a man standing on a sidewalk in Manhattan who the cop thought resembled a criminal he'd been trailing. Only it wasn't the criminal. It was James Blake, the retired black tennis pro.

BEYOND HIS ATTORNEY and his wife, Sefolosha consulted an inner circle of confidants that included his parents. His mother, Christine Sefolosha, a painter, was born in Vevey, an ancient and picturesque village of stone houses and cobbled lanes on the north shore of Lake Geneva. Her family has called it home for many generations. His father, Patrick Sefolosha, was born in South Africa, outside Pretoria, and raised mostly in a vast, plumbing-less shantytown called Mamelodi, one of the country's notorious black-people-only townships -- the apartheid-regime version of Indian reservations. He grew up to become a musician, the frontman and saxophonist for an Afropop band called the Malopoets. He wore his hair in Rasta-length dreads. The band signed a record deal with Virgin. It toured Europe and America and played New York City. The music was overtly political: anti-regime, pro-resistance. The New York Times once reviewed a Malopoets show at the celebrated world-music venue SOB's in Manhattan. The Malopoets' songs, the article noted, were mostly sung in the Sotho language and "turned out to be prayers for families torn apart through South Africa's resettlement policies, or exhortations to 'fight for your rights.' "

Back home, Patrick was constantly harassed by police, detained, beaten up, released. He does not remember how many times he was arrested. "Talking to you like this -- it's so behind me, more than 30 years -- it's: Did I really live that? Yes, I did. Those were not happy times. But I had to live them. You go through this kind of thing, you don't know anything else, you deal with it. You find a way not to be arrested. You are always trying to avoid trouble because trouble can be anything." One night while he lay asleep in bed, a Malopoets bandmate was murdered, likely by a pro-government death squad.

Patrick met Christine in Johannesburg after a show one night. She had moved to the country some years before with her then-husband, a white South African veterinarian she had met in Switzerland. After a time, she divorced the vet to be with Patrick. "I was not an activist then," she says. "But by becoming involved with Thabo's father, I became an activist." She was now on a list, a suspected member of the African National Congress, the major anti-regime armed resistance movement. She was arrested and detained by police. She says she received threatening phone calls in the middle of the night. Whites weren't allowed in the townships, so she sneaked into Mamelodi to see Patrick. She became pregnant with his child (Thabo's older brother Kgomotso). The apartheid regime had so-called miscegenation laws: No romance or "interbreeding" between white and black. For this transgression, he faced 10 years in prison. She faced an enforced abortion. In 1983, they fled South Africa and apartheid.

"I escaped that," Patrick says. "I escaped that especially for my kids. And then to see that Thabo has to go through this same kind of thing ..." His voice trails off. He has keenly followed the news of the killings of African-Americans by police in the U.S. -- Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray -- and the resulting protests. When he learned about what happened to Thabo in April, he says he felt enormous relief. "I was happy," he says, "because he wasn't killed. They only broke his leg."

THABO'S BROTHER KGOMOTSO urged him to fight; Bertille did the same. She said, "What about all the people that cannot afford this type of lawyer and get squashed by the system?" His mother urged caution: It's a dangerous thing to go up against a powerful system. Budenholzer, in a one-on-one meeting with Sefolosha, said he thought he should fight. Patrick Sefolosha told his son, "It is a matter of ... your honor." This is how Thabo Sefolosha puts it: "I believe what happened was an injustice. And looking at this, you think, 'Maybe this same type of thing happens to many more people. I am in a position where I can prove I'm innocent. Not many other people have that chance.'"

When Spiro informed the DA's office that Sefolosha was refusing the deal, prosecutors came back with a sweetened offer: They would strike the community service. But it wasn't enough. Sefolosha had made up his mind: It was either a full dismissal like the one Antic had received, or trial.

He felt he had no choice.

THE STAND

"He doesn't think the rules apply to him. He's a professional athlete, a member of the NBA. He can do what he wants to do. You are going to hear about how on April 8, 2015, the defendant displayed a sense of entitlement and disdain. Entitlement, in that he shouldn't have to comply to the rules everybody else has to." So said Assistant District Attorney Jesse Matthews in his opening remarks early on the second day of the trial, Oct. 6. A small bearded man, he was one of two ADAs assigned to prosecute Sefolosha.

When Sefolosha spurned the deal, the government seemed to go after him with the full weight of the office. According to a person with knowledge of the DA's office, investigators were temporarily pulled off a homicide case to assist in Sefolosha's prosecution. In the first minutes of the first day of the trial's proceedings, before jury selection had begun, one of the ADAs requested what's called a Parker warning. In essence this meant the DA wanted the court to consider Sefolosha a flight risk.

"Uh, no," the judge said.

The DAs even tried to add a fourth count -- harassment of a police officer in the second degree -- to the crimes Sefolosha was already accused of. Harassment wasn't on the original criminal complaint. The judge dismissed it.

During jury selection, the DAs asked a curious question of the pool of 25 Manhattanites, only three of whom were black. Would you be able to remain unbiased if the only witnesses produced by the prosecution were police officers?

THE PROSECUTION CALLED to the stand JohnPaul Giacona, 28 years old, from Staten Island, New York -- holder of a bachelor's degree in marketing from St. John's University, Staten Island campus -- three years and three months on the New York City police force. Shield No. 9996. Giacona is a member of the 10th Precinct's "cabaret unit" or "cabaret squad," which oversees the bars and nightclubs of Manhattan's upscale nightlife-heavy neighborhoods. In the 10th, it's not just 1 Oak but Avenue, Marquee, Dream, PHD, No. 8, Tao. The cabaret units make sure the crowds are orderly. They routinely deal with mouthy drunks. Says one veteran NYPD cabaret cop, "You become thick-skinned to that. This is what you're going to deal with. It becomes secondhand to us."

Early on the morning of April 8, Giacona was one of dozens of officers who responded to a crime scene. A man was down, bleeding from a stab wound. It would later be determined that this was Chris Copeland of the Pacers, formerly of the Knicks. Two women were also cut as they tried to hold back the perpetrator. Colleagues of Giacona had approached the perpetrator with their guns drawn. He still had a switchblade in his hand; Copeland's driver, the hero of the hour, had him in a bear hug; he dropped the switchblade. There was blood on the pavement. The injured male, in that moment, was judged "likely," as in likely to die. The order from the supervisory sergeant: Shut down 1 Oak and Artichoke, the all-night pizza place at 17th and 10th, immediately. Clear the block! As Giacona did this, he said, everyone was "very compliant." Only two males -- two very tall males -- were not. He asked them "politely" to leave. They were, he said, more interested in mingling and talking to girls. He was forced to approach the males a fourth, a fifth, a sixth time. Then one of the males said to him, "You're mad you're a midget. I would be mad too if I were a midget." Giacona is 5-7, 160 pounds. He was just trying to do his job. "We just want him to leave at that point," he said.

They called to the stand Daniel Dongvort, 28, from Smithtown on Long Island -- formerly an emergency medical service responder, with an associate's degree in liberal arts from Empire State College -- almost four years on the force. Shield No. 3129. He too responded to the stabbing. He rendered first aid to the victim, Copeland (who would, in fact, go on to survive his injuries), and helped him into an ambulance. He was then assigned to crime-scene security. Dongvort first saw the defendant speaking to Officer Giacona near the corner of 17th Street and 10th Avenue. The defendant, Dongvort said, was being mouthy: "He was calling him a midget repeatedly." Sefolosha and Antic refused to leave the area after "multiple requests from many officers." He, Dongvort, opened the door of a livery cab for the defendant and urged the defendant to enter the automobile and go home. But just then "another unknown male" grabbed Dongvort's attention. He tried to escort this other male away from the area. As he was doing so, he could see out of the corner of his eye another of his colleagues and the defendant involved in some kind of commotion. He went over to assist.

They called to the stand Richard Caster, 28 years old, from Rockville Centre -- formerly a TSA employee at LaGuardia Airport, degree in U.S. history from C.W. Post Long Island University -- on the force for more than three years. Shield No. 17276. He first noticed the defendant because he was "not complying with instructions from Officer Giacona." Meanwhile, "everyone else was compliant." When Caster was standing near the corner of 17th and 10th Avenue, he saw the defendant charging and lunging at his colleague, Officer Dongvort. "The charge was an aggressive motion." He took action. He "stepped in" before the defendant could make contact with Officer Dongvort. He took the defendant by his right arm. He informed the defendant he was under arrest and told him to put his hands behind his back. But the defendant refused. He resisted. He was "straightening his arms." Sefolosha is a large man, approximately 6-7 and 230 pounds. Officer Dongvort came to assist in the arrest. So did several others, including Officer Giacona, who swept Sefolosha's legs. It was a "proper takedown," Caster said. Officer Giacona put the handcuffs on.

The five officers involved in the arrest of Thabo Sefolosha -- Giacona, Dongvort and Caster, as well as others named Michael O'Sullivan and Jordan Rossi -- were not made available for this story. They were each being investigated by Internal Affairs and the CCRB. (Giacona and Caster were later found guilty of unlawful abuse of authority, with recommended punishments of up to 15 days of docked vacation time for Giacona and formalized training for Caster.) Their union, the Patrolmen's Benevolent Association, also declined to comment or make the officers' union-provided attorneys available for comment. The DA's office declined to comment as well. The accounts above are based on trial testimony and statements made by the officers to CCRB investigators.

"WHERE DID YOU grow up?" Assistant DA Matthews asked early in his direct examination of Caster.

"Long Island, New York, raised by my parents," Caster said, and without further prompting he added: "My father's black, mother's white."

His father is Richard C. Caster, 67 years old, a former All-Pro tight end with the Jets, Oilers, Saints and Redskins, who grew up in Mobile, Alabama, and played football on scholarship at Jackson State, a historically all-black college in Mississippi. In May 1970, his senior year, police opened fire with shotguns on a group of Jackson State student protesters, killing two and injuring 12. "Listen," Richard Caster said when I spoke to him recently by phone. "I was brought up in the South and only came up here for the first time as a 21-year-old." He added, "I was right in the heat of everything." And then he said he thought it best if he didn't say anything more.

SPIRO'S FIRST QUESTION to Giacona in cross-examination was, "Officer, will you use that marker and mark on the easel when you first noticed that my client was black?"

"Objection, your honor."

"Sustained."

Spiro proceeded to slowly undermine Giacona's recollection of events -- and that of the other officers. He got Giacona to say he didn't really know how many times he'd approached Sefolosha to tell him to leave the block -- that the six times Giacona had sworn to, a number that appeared in the original criminal complaint, was potentially false. The line of questioning suggested it was a high-side estimate put into the report to strengthen the case against Sefolosha. Spiro got the officers to agree that, yes, when Sefolosha was arrested, there were many other civilians closer to the crime scene, as captured by the CCTV cameras. He asked Giacona, "You've never seen the video of you walking by the Caucasian individuals and walking right up to Mr. Sefolosha?" After playing the footage, Spiro eventually got Giacona to agree that this had happened.

"Are there lots of people closer than Mr. Sefolosha?"

"I would say so, yes."

Using NYPD documents he'd obtained from a friendly source within the department, Spiro showed that the officers originally wanted to charge Antic with attempting to punch Dongvort -- an allegation clearly refuted by the CCTV footage and the TMZ videos. Spiro noted that in the TMZ videos you can hear many voices saying many things but never the words "Put your hands behind your back" or "You're under arrest," which the officers testified they'd uttered repeatedly while trying to corral Sefolosha. Spiro got Caster to agree that, yes, it was possible that Sefolosha was trying to give money to a homeless person and that maybe Sefolosha hadn't been making an aggressive move toward Dongvort at all. Then Spiro produced the homeless man.

ON THE STAND on the third day of the trial he wore a big knit cap, a denim vest and baggy black pants. He chewed gum as he testified. He said his name was Amos Canty. He looked to be in his late 40s or 50s. He testified that he "works" for the bouncers at 1 Oak, performing whatever tasks -- setting up partitions, hailing cabs for clubgoers -- they ask him to. He testified he's not above asking the VIPs for money, including Sefolosha on the morning of April 8, at the corner of 17th Street and 10th Avenue. He testified that Sefolosha tried to give him money but that he never got it because an officer intervened. He testified that he then saw several cops take Sefolosha down. Spiro's investigator Herman Weisberg, a former NYPD detective, says Canty almost didn't take the stand on the day of his testimony. When Canty saw the 10th Precinct cops in the courtroom, he got scared. And on cross-examination, Assistant DA Francesca Bartolomey tried her best to impugn him.

"Were you paid for your testimony today?"

"Was I what?"

"Were you paid for your testimony today?"

"Hell no! Somebody supposed to be payin' me?" The courtroom erupted in laughter.

"Is your name Renard Dobson?"

"No, that was an alias name I had. I had ID made from another country, yes. Wait, wait, I'm on trial here or something?"

"Is your name Walter Jordan?"

"Don't worry about my name, I'm not on trial."