A Racing Mind

Dale Earnhardt Jr. returns at Daytona after letting his brain heal from multiple concussions -- and after undergoing a different sort of rehabilitation for his psyche.

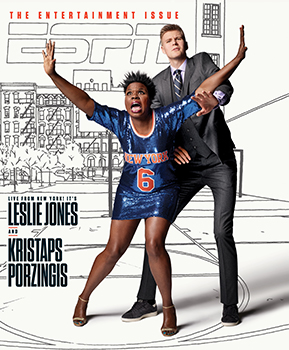

This story appeared in ESPN The Magazine's Feb. 27 Entertainment Issue. Subscribe today!

Darlington Raceway on a Wednesday in December is vast and cold and empty. Dale Earnhardt Jr.'s crew works alone in the garage, making last-minute tweaks to his race car. The car is stripped of paint and decals, down to bare primer -- gunmetal gray. There are no fans, just a NASCAR official and a Charlotte neurosurgeon. Today is not about money or trophies. It's about whether Dale Jr.'s brain has healed enough to do what his heart needs so bad.

A helicopter comes in low over the rim of the track and lands with a kiss in the infield. Dale Jr. climbs out. His soon-to-be-wife, Amy Reimann, was supposed to be with him, but there was a mix-up over the time, and he couldn't wait on her -- the chopper needed to leave the house in North Carolina while their four buffalo were across the pasture. The buffalo freak when the helicopter gets close. Dale Jr. leads a big life. There are occasional buffalo problems.

He doesn't like going anywhere without Amy. "I'm his Binky," she says. She calms him when he worries, and he worries all the time. Mostly he worries about letting down all the people who care about him. Time and again his family has crashed and broken, through death and divorce and detachment, and he has spent his life welding the scraps together. He worries that it will fall apart again if he's not a good enough driver and a good enough man.

"I always make things worse than they are, or create problems that aren't there," he says. "And going and doing some simple task becomes a problem. I start imagining problems that aren't there. What people are going to think, who's going to judge me and am I going to be good enough, am I worthy?"

He thinks of his confidence as a battery. Some mornings when he wakes up, it is cold and dead. His legion of fans, his loyal crew, his best friends, the woman he has fallen in love with -- in his low moments, he sees them as blessings he didn't earn and doesn't deserve. Sometimes he believes he is what he is only because of who his daddy was.

He is at Darlington in December because of Michigan last June. On the 62nd lap of the FireKeepers Casino 400, he got bumped and slid high up the track. The right side of his car hit the wall -- back end first, then the front, a double tap. He had a history of concussions. He knows of at least four others in his career, but this didn't feel like that at first. He brushed it off as allergies, or maybe a sinus infection. He ran three more races, jostling his brain even more with the normal pounding of life in a race car. Then the symptoms caught up with him. Suddenly he couldn't walk two steps without stumbling. His eyes vibrated in their sockets. He fell into dark moods he couldn't shake. He ended up sitting out 18 races, the entire back half of the 2016 season. Some days he thought he might have to retire. Other days he thought he wanted to.

Over months of rehab, he found his way out of the fog. But to race in 2017 -- beginning with the season-opening Daytona 500 on Feb. 26 -- he needs medical clearance from NASCAR. The last hurdle is this test at Darlington. NASCAR normally limits testing to a few scheduled sessions. But while Dale Jr. was out, NASCAR passed an exception allowing drivers who missed time for medical reasons to run one extra private test. It might as well have been called the Dale Jr. Rule. The NASCAR official is here to make sure the crew doesn't gather extra data on the car, which would be an unfair advantage. The neurosurgeon, Jerry Petty (no relation to legend Richard Petty), is here to check on Dale Jr. between runs. In his 18 years at NASCAR's highest level, Dale Jr. has run 169,682 laps in competition. These laps at this empty track might be the most important of his life.

Dale Jr. puts on his helmet and gets in the Chevy SS. Adam Jordan, the crew member responsible for the car's interior, leans through the window to make one last check. He swears he can see Dale Jr.'s heart pounding under his firesuit.

An interesting thing happened to Dale Jr. in those five months out of the race car: He demanded less and listened more. He has always been a living contradiction -- part people pleaser, part selfish and spoiled. In his time off, he focused on shedding the side he doesn't like. "The person I became in that little moment is the person that I always want to be," he says.

And here is his conflict: Can he hold on to his new self and still keep the edge it takes to survive on the track?

He is 42 now, and he knows that someday soon he will have to give it up. But now, in Darlington, he flicks the ignition switch and the engine explodes to life. He pulls out of the garage and rumbles past the ambulance with the EMTs waiting, just in case. He jerks the wheel left and pulls onto the track. Everyone else is behind him now. This is the part he has to do alone.

With his hair bleached electric blond, Dale Earnhardt Jr. proved a striking contrast to his father's old-school image. Craig Jones/Getty Images

He looks at the crowd ahead and draws a deep sigh: "So many people."

We're in Miami in late November, three weeks before that day in Darlington. Dr. Micky Collins, Dale Jr.'s concussion specialist in Pittsburgh, has been telling him to get out of the house and stress-test his brain. No better place for sensory overload than a racetrack. So Dale Jr. has been visiting for the past few races, hanging out in the pit box, doing some TV and radio work. On the morning of the Ford EcoBoost 400 at Homestead-Miami Speedway -- the last race of the season -- Dale Jr. has a full schedule of meet-and-greets with sponsors and fans. At most tracks, his people take him around in a Tahoe with emergency lights. Nobody knows it's him, and everybody gets out of the way. But at Homestead, some gates are too tight for a car to get through. The only option is a golf cart.

Dale Jr. is by far NASCAR's biggest star -- fans have voted him most popular driver 14 years in a row. Thousands of those fans are ahead of us on the plaza outside the track. Imagine the crowd outside the Oscars and Will Smith rolling up on a scooter. That's what this feels like.

Kenny the driver guns the cart as best he can, but sometimes he has to dial it down to walking speed. Nobody's expecting Dale Jr. to ride by, so most people don't notice until he's right up on them. When they do, it's a highlight reel of double takes.

Holy s---, that's Junior!

Hey, Dale, I was in the Navy, can I get a picture?

Dale, I'm your biggest fan! I'm from Canada!

Dale Jr. mostly stares straight ahead. He's good about signing autographs, but if he stops out here, the fans will fall on him like zombies.

We pull up to a side door, and everybody jumps off the cart the instant it stops moving. Now we're in a commercial kitchen, quick-cutting past startled cooks shredding cabbage, a scene from a Jason Bourne movie. We wind through three rooms and dive into a service elevator somebody has held open. Two chefs are standing in the other corner, staring.

The elevator is slow.

That universal awkward elevator silence sets in.

One floor.

Another.

Dale Jr. looks over at the chefs.

"Cooking for a lot of people today?" he says.

Then the door pops open and he's speed-walking out. First it's the Goodyear suite, then Axalta, then a tent full of people from Nationwide. At every choke point, fans block his path. One woman plants herself 6 inches from his face and won't move until she gets an autograph. It's a no-win moment. Stay and you get mobbed. Leave and you've pissed off a fan. He jumps on another elevator and slumps against the back wall. "If I was racing today, I wouldn't do this," he says. "I'd be saying 'Hell no.'"

But he knows better. This is the price of his life. He's had a thousand days like this since he started racing in the Cup series -- NASCAR's premier league -- back in 1999. Budweiser signed him to an eight-figure sponsorship deal and started the "Countdown to E-Day" four months before his first Cup race. He was the namesake son of Dale Earnhardt, NASCAR's outlaw god. No incoming driver has ever been more hyped. Dale Jr.'s career came preloaded with hundreds of thousands of fans.

Back then he cared only about the one who shared his name.

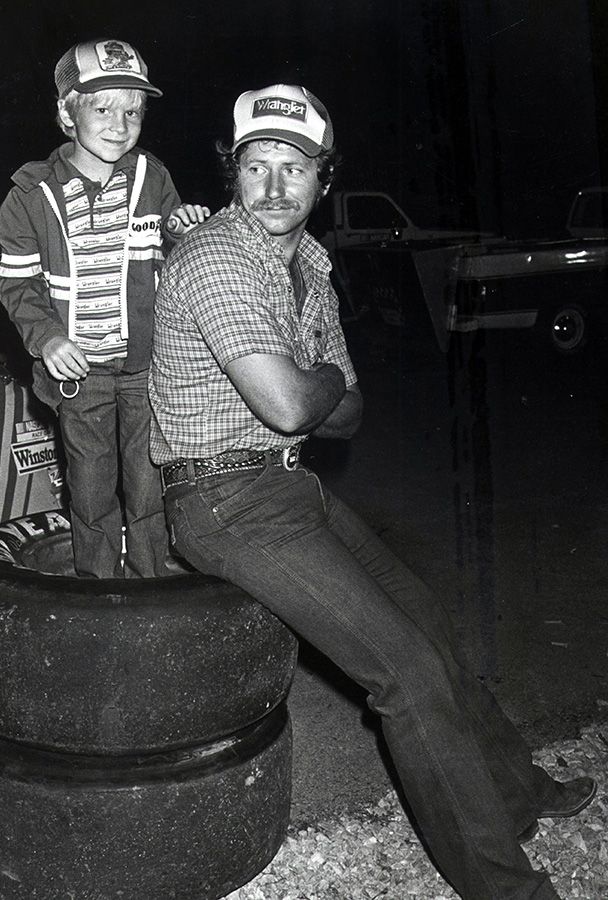

Dale Sr. and his wife, Brenda, divorced when Dale Jr. was 2. The kids -- Dale Jr. and his sister, Kelley -- went to live with their mom. But in 1981, when Dale Jr. was in first grade, their house burned down.

Dale Sr. and his future wife, Teresa, took in the kids. Coming off his first Cup championship, racing consumed Dale Sr.'s life. Nannies and relatives raised the children. Dale Sr. loved his kids, but he demanded control -- when they went out to eat, he told everyone exactly where to sit. He gave them everything they needed except what they craved: his time and attention. "You didn't sit down and have a conversation with Dad about your school or what was happening in your life," Kelley says. "There wasn't this sense of family in our family."

Kelley dealt with it by keeping quiet and studying. Dale Jr. dealt with it by leaving cereal bowls under his bed and getting kicked out of Christian school. They took different paths for the same purpose: to get closer to their father. That's why Dale Jr. got into racing. He just wanted his dad to notice him.

Without their dad's help, Dale Jr. and Kelley raced short tracks in the Carolinas with their half brother, Kerry. A lot of people still think Kelley was the best of the three back then, but Dale Jr. had more than just a name. Every top driver has some world-class skill: peripheral vision, spatial awareness, a sense of what to do by how the car feels in the seat. (That last one is called "driving with your ass.") Dale Jr.'s biggest skill is how fast he can process what he sees -- the circuit from eyes to brain to body that turns the shaky blur on the track into a tap of the brakes or a turn of the wheel.

With the help of his half-brother, Kerry, Dale Jr. raced a Monte Carlo at short tracks in the Carolinas. Courtesy Earnhardt family

His dad noticed. In 1996, when Dale Jr. was 21, Dale Sr. gave him a car to race in what was then called the Busch Grand National Series, NASCAR's version of Triple-A baseball. Dale Jr. won two championships at that level, in '98 and '99. In 2000, when he graduated to his first full Cup season, he and Dale Sr. won two races apiece. Even better, they had gotten to know each other as father and son. They scrapped like any other drivers on the track -- Dale Sr. threw a shoe at Dale Jr. after getting bumped in an exhibition race in Japan -- but they also spent afternoons sitting around and talking, getting caught up on the time they had missed. It was how Dale Jr. had always hoped it would be.

Then in the first race of 2001, on the last lap at Daytona, Dale Sr. hit the wall and died.

We will come back to that moment, but for now, know this: It left Dale Jr. unmoored. He was 26, and his father was the only authority he respected. And the fans who mourned Dale Sr.'s death projected their grief -- and their hopes -- onto his son. They missed the man who wore the thick mustache, spun out cars blocking his way and woke up every morning to Lynyrd Skynyrd's "Gimme Back My Bullets." Dale Jr. bleached his hair blond and went around cars instead of through them and listened to Pearl Jam. Fans still loved him, but more than anything, they wanted him to be his daddy. It never turns out that way.

He had partied hard before, but now he devoted his life to pleasure. It didn't take him and his buddies long to empty the two cases a week Budweiser sent him. He hung out with Kid Rock. His house outside Mooresville, North Carolina, north of Charlotte, had a giant basement he called Club E. He showed it off on MTV Cribs. Sometimes he'd have 250 people down there drinking and dancing and smashing furniture. Budweiser also gave him a boxing ring, where he sparred with friends. He didn't know how to act normal. Nothing about his life had ever been normal. A lot of 20-something men just hope for a date on a Friday night. Dale Jr. got hired by Playboy to take photos of naked triplets in his garage.

He still won races -- 15 in his first five years as a full-time Cup driver -- but he went even harder on the off-days. As his 20s faded into his 30s, the mornings felt more empty. He wondered through the hangovers: Why the hell am I living like this? In some ways, partying filled the same hole racing did. It made him part of a group, made him feel like he was worth something. It was a way to chase after the family that always felt a car length away.

His life off the track wasn't good for his mind. His life on the track wasn't good for his brain.

Amy, with Gus and Junebug, is a grounding force in Junior's life. Josh Goleman for ESPN

When he talks about his concussions, Dale Jr. has a hard time keeping them straight. They're variations on the same horror story.

In 1998, racing at Daytona in the Busch series, he collided with Dick Trickle and went airborne backward. His car barrel-rolled and bounced off Trickle's hood before landing, somehow, upright. When he got out and tried to do an interview, he fell down. Later on, his crew noticed that the wreck had thrown him sideways so hard that he had bent the door with his helmet. They all laughed about it.

In 2002, at the Napa Auto Parts 500, he got tangled with Kevin Harvick as Harvick dove for pit road. He went headfirst into the wall in nearly the same way Dale Sr. had done the year before. He hid his symptoms from his team and drove with a concussion for three months afterward. When NASCAR found out, it put in a new rule giving doctors at the track more authority to demand concussion tests after a wreck.

In 2012, during a test at Kansas Speedway, one of his tires blew out and he went straight into a fence at 190 mph. The moment just before he hit was the one time he thought he was going to die. He felt sick at dinner afterward, but he had seats in the owner's suite to a Washington Redskins game that night -- he's a lifelong fan -- so he and Amy went ahead and flew to DC. Now, when he thinks about it, the whole day feels like a hallucination.

Six weeks after that, he got trapped in a four-wide pack on the last lap at Talladega and got hit from both sides in a massive wreck involving 25 cars. Steve Letarte, his crew chief at the time, called him on the radio: You OK, buddy? Dale Jr. replied: I don't know, man. I mean, I don't know how many of them hits like that I can take. Doctors concluded that he'd had two concussions: one from that crash and one from the wreck in Kansas. NASCAR ordered him to sit out the next two races. That was the first time he rehabbed with Dr. Collins.

No one knows the risks of racing more than the son of Dale Earnhardt, and Junior (in the 88 car) has become an example of the changes in how concussions are handled. Jamie Squire/Getty Images

Those are just the concussions he's sure about. Like every other professional driver, he has wrecked dozens of times -- all the way back to when he was a teenager, fiddling with his new CD player, and flipped his Chevy truck on Christmas morning. His career is a timeline of concussion awareness in sports. In '98, laugh it off. In '02, keep driving. In '12, miss a couple of races. In '16, sit out half a season.

NASCAR, like other sports leagues, is trying to keep up. In 2014, it started requiring baseline concussion tests for drivers before each season. The ImPACT test measures short-term memory, reaction time, attention span and problem-solving. Drivers who wreck take the test again, and doctors compare the results to check for impaired brain function. (Some scientists question whether the ImPACT test really works, and some researchers are concerned that it frequently shows false positives. Still, sports teams and leagues around the world use it, including teams in the NFL, the NHL and MLB and in collegiate and high school sports.)

The nature of racing presents problems other sports don't have. After a big wreck, it's easy to check a driver who has to get out of a crumpled car. But what if the car can still go? Drivers steer bent-up cars back onto the track all the time -- the longer they stay in the race, and the higher they finish, the more they get paid. Doctors can't check a driver who doesn't pull over. And if NASCAR changed the rules to park any car involved in a crash, drivers -- and fans -- would be furious.

Drivers on the IndyCar open-wheel circuit wear earpieces that measure the forces on a driver's brain in a crash and send the information to an impact data recorder -- a "black box" -- that's installed in every car. Officials study the data and, based on their guidelines, can force a driver to sit out at least the next week. NASCAR cars have had black boxes since 2002, the year after Dale Sr.'s death pushed the sport to make cars and tracks safer. But drivers don't have the earpieces, so NASCAR can't tell with any precision how a crash directly impacts a driver's head. And, at least officially, NASCAR doesn't use the crash data to decide whether a driver should sit out a race.

Still, NASCAR drivers are paying attention. Carl Edwards nearly won the Cup championship last year before wrecking at Homestead-Miami with 10 laps to go. But in January he announced that he was stepping away from the sport at age 37 and mentioned Dale Jr.'s concussions as a factor in his decision. "I don't like how it feels to take the hits that we take," Edwards said. "I'm a sharp guy, and I want to be a sharp guy in 30 years."

The major problem in racing is a theory of relativity. The long-term risks of concussions are now clear to most athletes. But race car drivers risk much worse every time they pull onto the track. No one knows that better than the son of Dale Earnhardt.

Back in November, when Dale Jr. was doing one of those Homestead-Miami meet-and-greets, he talked about how the race there doesn't start until midafternoon. That means that midway through the race, the sun sets straight into the drivers' eyes. For half an hour, on every lap, the drivers come out of Turn 4 and for a few seconds their windshields turn white with glare. They can't see 15 feet in front of them. "Like flying through a cloud in a plane," he said.

Imagine being behind the wheel with 40 drivers on the track, all going 130 mph, all basically driving blind. Later on, I ask Dale Jr. about it: Doesn't that scare the crap out of you? He shrugs. He's got a spotter to tell him what he can't see. He trusts the other drivers. It doesn't last that long. All of which is to say: His nightmares are different from yours and mine.

In the early days, such as this scene after winning the Pepsi 400 in 2001, Dale Jr.'s friends were always part of the party. Donald Miralle/ALLSPORT/Getty Images

Now we're in Las Vegas for the NASCAR banquet, a week before the test at Darlington. Dale Jr. and Amy sit down to lunch at a restaurant in the Wynn hotel. The server brings by a tray of red velvet cake macarons. Dale Jr. has never had a macaron. "Holy moly," he says.

Back in the summer, after the concussion, Vegas would have felt like hell. Five weeks into recovery, nothing was getting better. His eyes still shook so bad he couldn't focus. He stumbled in the aisle at Sam's Club. His face clouded over and he got extra quiet -- the surest sign he was in a bad mood.

The people close to him cared about his recovery as a person but also as a driver, because with Dale Jr. it is all mixed together. Kelley runs JR Motorsports, which handles his marketing and fields a team of drivers in the sub-Cup circuits. His mom works there in accounting. Rick Hendrick -- owner of Hendrick Motorsports, the team Dale Jr. drives for -- has known Dale Jr. since he was a child. Three years after Dale Sr. died, a Hendrick Motorsports plane crashed in Virginia. One of the 10 people who died was Ricky Hendrick, Rick's only son. In some ways, Hendrick says, he and Dale Jr. have been parent and child for each other ever since: "I've kind of filled the role in his life, and he's filled a little of that role in my life."

(The one family member Dale Jr. doesn't spend time with is his stepmother, Teresa Earnhardt. They separated professionally in 2007 when Dale Jr. left Dale Earnhardt Inc. -- which Teresa ran -- to race for Hendrick. They haven't had much contact since.)

Every morning that Dale Jr. woke up and lost his balance was another morning that millions of dollars in decisions had to wait. Sponsors were already making plans for 2017 and wondered whether he was coming back. His team didn't know from week to week whether he'd be driving the car.

He tried to speed up his treatment, but it was like he was stuck in sand. Collins prescribed a mild anti-anxiety drug. He put the word out to Dale Jr.'s family and team: Don't keep checking on him. Don't even ask how he's doing. Give him some space for a while.

The only one who saw him every day was Amy.

They met in the fall of 2008, when he decided to tear down his old house and build a new one. She was an interior designer for the team he hired to do the work. Dale Jr. talked T.J. Majors, his spotter and one of his best friends, into tagging along to the meetings about the house. You have to see this girl, Dale Jr. said. T.J. watched them look at each other across the table.

It wasn't an easy beginning. Amy had been married and split from her husband. Dale Jr. had been with lots of women, but he'd never learned how to treat one.

He'd call his buddies, and they'd call their buddies, and there'd be 100 people at the house before Amy knew what was going on. "When me and Amy first met, I was super selfish," he says. "We're doing whatever I want to do. You wanna do what I wanna do, right? Yeah, we're doing it."

Amy wondered why she had moved to North Carolina. They had multiple come-to-Jesus moments, but none stuck. Dale Jr. was still determined not to grow up. He stayed up all night playing video games. His friends brought him takeout for supper. But every so often the kind side of him would come out, the side that wanted to make her happy. It was just enough to hang on to. She stayed. And slowly, Dale Jr. realized he wanted her to.

"I don't know what the turning point was," Amy says.

"I do," Dale Jr. says. "In my heart and mind, it's always been Jane."

Jane is their couples therapist. They've been seeing her for three years. It was Dale Jr.'s idea. He has been in counseling of one sort or another, off and on, since he was 11 or 12. He also has seen it work for other family members. Jane was the one who helped him understand that he was committed to the wrong things, that he was worthy of a better life.

Looking back, he sees what a jerk he was -- to Amy, to his crew, to anybody who tried to get him to do anything besides what he wanted to do. Part of it was his anxiety, which led him to cut relationships short before they went bad. Part of it was the entitlement of being a millionaire when he barely needed to shave. Part of it was the worry about being discovered as a fraud who didn't deserve any of it.

And part of it, he knows, traces to his childhood, to the little boy playing with Matchbox cars while his dad was gone racing real ones. Dale Jr. is not ready to dig quite that deep yet. He just knows he spent years going in the wrong direction.

"I ran that course for so long," he says. "Too long. I had had enough. But I didn't know how to be a good person."

For Amy, he learned. He started listening. He kept more regular hours. When they built the new house, they redid the basement. It's still spectacular -- a theater, a karaoke rig, an old Chevy truck they turned into a DJ booth. But these days Dale Jr. is more likely to listen to old LPs down there while Amy has a glass of wine. It's not Club E anymore.

After the concussion, Amy woke him up every morning to do his rehab work. He shot baskets and flung medicine balls. He did elaborate vision drills -- reading a tiny eye chart he held out in front of him while he walked forward and backward, shaking his head back and forth. He stumbled around in a dark room with swirling lights so his body could learn to get its bearings again. Nearly two months into rehab, he finally started to get better. His stress level dropped. And as it did, he noticed he had become a different man.

He came back to his race shop to hang out with his crew, and over sushi at a place down the road, they bonded again. He jumped back onto the team message board, where they share race info and give one another unrelenting grief. The crew members had been able to tell, just from his body language, when they needed to take the long way around him. Now he walked lighter.

For years, Dale Jr. had mapped out his life to the hour -- he clung to routines because new things made him anxious. But now he had free time and a desire to improvise. He and Amy took a last-minute trip to Texas to see her parents. They flew to a music festival in Milwaukee just to see a band they loved, Lord Huron; Dale Jr. stood in the crowd, anonymous.

Back home they went to the Cabarrus County Fair with Greg Ives -- his crew chief since 2015 -- and Ives' wife, Jessica. They went down to watch the pig races. Dale Jr. walked down the midway, a version of that dark rehab room with the swirling lights. This time he didn't stumble.

He even tried a few rides. He and Amy climbed into one that was a version of the classic Gravitron -- you get into a big cylinder, stand with your back against the wall and hang on as it starts to spin. The force of the spin presses you backward. You feel like the world is about to drop out from under you.

Amy almost threw up. Dale Jr. was wobbly when it was over. But they survived the ride together.

Dale Jr. got to know his father best through racing, which is one reason he keeps doing it despite its toll. Racing Photo Archives/Getty Images

Dale Jr. puts his head in his hands: "I am so sick of talking about myself."

Some of the old Dale Jr. has returned this afternoon, mid-December, a week after Darlington. We're at his and Amy's house, which he doesn't like to show to strangers. He got here late because another appointment ran over. He has to pose for photographs. He's being polite. But normally he talks in paragraphs. Now everything he says is two or three words.

He's down on himself today too. Racing is not that hard, he says. Most anybody could do it. The walk back to the motor coach at Bristol wears him out more than the race.

Dale Jr. has lived his complications in public while he agonized over every one in private. This couch we're sitting on is where he and Amy curl up with Gus, their Irish setter, and laugh at Junebug, their Pomeranian. The bedroom upstairs is where he can't sleep unless he drapes himself over Amy.

This is a place for family. We're not family.

He perks up once. I mention all the odd things he has collected on his 200 acres. There's an Old West town, a replica gas station, a custom treehouse, a six-hole pitch-and-putt golf course. Strewn through the woods are carcasses of old race cars he has collected for years. I mention how weird it will be when somebody digs this place up 10,000 years from now.

"That's right," he says. "I want people to wonder what happened here."

History matters to him. He still has the Redskins helmets and uniforms his mom gave him for Christmas when he was a kid. He has a private server with recordings of hundreds of NASCAR races going back to the '50s. He proposed to Amy at a church in Germany, in the town where he had traced the Earnhardt family back 10 generations.

While the photographer works, I wander into a hallway off the living room and find a little museum of history: the history of Dale Jr. and his dad. Here are two of Dale Sr.'s firesuits. There's his application to race in NASCAR. Follow the pictures down the wall and you see Dale Jr. turn from boy to teenager to grown man with Dale Sr. by his side. Dale Jr. didn't used to keep many pictures of his daddy around. But that was before Daytona in 2001.

And now we're back to that moment.

Dale Sr. was running third when he hit the wall. The two drivers in front of him both drove for his team. Michael Waltrip took the checkered flag -- his first win in 463 Cup starts. Dale Jr. finished right behind him in second. NASCAR fans will argue until the Rapture about what Dale Sr. was doing on that last lap. Was he trying to win the race, or blocking the rest of the field from catching his friend and his son? The story ends the same either way. He spent his last moments at his son's back.

NASCAR races at Daytona twice a year. The July after his father died, Dale Jr. headed to Florida early. There used to be a week off before the Daytona summer race, and for years he and his buddies had enjoyed the beach before the crowds showed up. That year, when they got to town, they went to the speedway and found the gate open. Dale Jr. drove his Suburban onto the track. They were going about 35 when a security guard cut them off, furious. Then he saw who was driving. He let Dale Jr. finish the lap.

They got to Turn 4. The skid marks were still on the track.

Dale Jr. got out and took a walk around. He didn't know how he would feel. He just tried to soak in everything in his life, and his father's, that had put them in that place together. "If I had any issues, I was going to find out that moment," he says. "And I didn't."

He decided then that Daytona would always be sacred to him.

A week later, in the first race at Daytona since his dad's death, Dale Jr. won the Pepsi 400.

Sixteen years later, Daytona will be where his comeback starts.

He feels 100 percent healthy, though he knows each concussion makes it easier to get the next one. He plans to donate his brain to science. Maybe it will help make racing safer, but racing will never be safe. The danger is the attraction. Dale Jr. talks about how you can get an inch or two from the wall at some tracks and compress the air into a cushion that makes the car go faster. But get too close and you're into the wall. That's the thrill of it -- that tiny space between joy and disaster.

Off the track, for now, he has found the cushion. He and Amy got married on New Year's Eve. They Instagrammed their honeymoon in Hawaii, drinking cocktails and watching whales, looking happy and relaxed. Dale Jr. hopes he and Amy have children. Most of the people close to him already have kids. It is a different kind of race, and he is behind.

He also wants to run fast on the track. He wants to win more races -- he has 26 wins in his Cup career -- and maybe the Cup championship he has never won. He's on the last year of his contract with Hendrick. He plans to race for a couple of months, see how he feels, before he decides whether to sign up for more. After his time off, retirement no longer feels like a distant notion. "I've done everything I ever thought I would do," he says. "I've done more than I thought I was capable of doing. I look at my trophies and can't believe they're mine."

But his mind is still not quite settled. As much as his time off made him a better human being, it couldn't replace the feeling he gets inside a race car -- that happiness at making so many other people happy. "I've had a hard time trying to find something that's comparable," he says.

He wouldn't race if nobody was watching. That's the whole point. He wants his fans to watch him, he wants his team to care about him, in the same way all those years ago that he wanted his daddy to notice him. That's why he got in the car. That's why it's so hard to get out.

Racing has wrecked his family and battered his brain. But he has hauled it all back to the shop and rebuilt it one more time.

Back at Darlington, that Wednesday in December, Dale Jr. tears around the track at 170 mph, running 15 or 20 laps at a time. He pushes hard enough to give his car a classic "Darlington stripe" from scraping the wall. Every time he pulls back into the garage, Petty -- the neurosurgeon -- runs him through a series of tests. He balances on one foot, closes his eyes and touches his nose. He shakes his head back and forth, focusing on Petty's finger in front of him. Petty gives Collins updates on the phone. Dale Jr.'s brain does everything they ask it to do.

The sun is getting low. Dale Jr. can already tell he'll be medically cleared, he knows he'll get to race at Daytona, but he's got time for one more run. He gets back into the car. His heart beats calm and steady.

Again, he fires up the race car. Again, he pulls out of the garage and past the ambulance. Again, he turns out onto the track. He mashes the gas and disappears around the first turn. Sometimes a man has to go in circles to find himself.