When there is no tomorrow

In watching the Indians on their historic streak, it became clear the most remarkable thing about the team wasn't the wins.

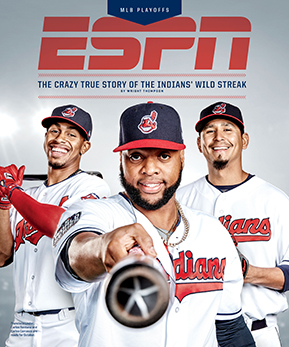

A version of this story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Oct. 2 MLB Playoffs issue. Subscribe today!

The Cleveland Indians return home in the middle of the night, winners of 15 straight and counting, and the feeling on the plane is something like an army or a rock band marching across a continent, exhausted but connected on a soul level: brothers in arms. The next day, the players head back into work. A light breeze blows across the stadium's empty concourses, which smell like popcorn and butter. They haven't lost in two weeks, pounding down the season's backstretch, playoff-bound. Their manager, Terry Francona, makes the two-block trip from home on his scooter, waving at cops and other working men. In the clubhouse, he swims to help the circulation in his injury-ravaged legs. He had heart surgery two months ago and missed only six games, the son of a pro ballplayer and the father of a combat-hardened Marine.

An old security guard named Bill, who brought his lunch in a plastic sandwich bag, sits outside the clubhouse. A sign on the doors says PRIVATE. It specifies no wives, no agents, no attorneys, just "immediate male family members" -- listing as appropriate fathers and grandfathers, brothers and sons. Nothing in pro sports is quite like a baseball clubhouse. Not merely a place for dressing and undressing, it's a shadow opponent -- more akin to a golf course than a football locker room. Individual games might be won or lost on the field, but seasons are won or lost in the endless hours between, 162 games in 183 days, the grind itself as difficult as any other physical aspect of the sport. Ballplayers are famous for superstitions and hardwired routines, for talking to bats and pissing on their hands, for destroying coolers and screaming at reporters and at each other. All those things are outward reflections of the inner anxiety that grows day by day, series by series. They often publicly mock their fragile attempts to impose order on chaos, whistling past the graveyard of broken baseball dreams.

This brings us to the shrine in the back left corner of the Indians' clubhouse.

The centerpiece is a large statue of Jobu, the Voodoo god from the movie Major League, which is of course about a winning streak. It's evolved over the past two seasons to include the main Jobu plus three smaller satellite Jobus. Two cigars rest beneath the large idol, and another stands upright in a shot glass. Someone has left an offering of Yves Saint Laurent cologne. A fan has sent in a potato; they've dutifully put it on the altar, which is actually just a plastic office cabinet. Now the potato is sprouting. It's a little gross. There's an incense holder that says "Party at Napoli's House" and a package of incense. There are three airplane bottles of Bacardi and, standing sentry on either side of the centerpiece statue, two fifths of Jobu brand rum, which is actually a thing.

"Very bad to touch Jobu's rum," says two-time All-Star Jason Kipnis.

The shrine is clever, a pop culture reference, mocking the very idea of a streak, even a meta commentary on the premise that a group of guys can put aside differences in pursuit of a common goal. It's clearly a joke, right? Well, of course it is, because what kind of crazy person creates an altar for a pagan movie god? Except ... a local television station wasn't allowed to film it. Freshly back from an 11-day road trip, Kipnis looks down and sees a yellow Post-it note with a carefully drawn henna-tattoo-looking design, left without explanation, an offering to whatever fickle forces control baseball streaks. The drawing wasn't there when they left town.

He smiles.

"This is new," he says.

Francisco Lindor (standing) bought everyone matching oversized blue plush robes after 18 wins. Jason Miller/Getty Images

The Indians win seven more before losing to the Royals, setting a record of 22 straight victories, passing such teams as the 1947 Yankees and the 1935 Cubs. For the players, the streak doesn't feel like an assault on history. They live the same mundane day over and over again. They come in early and do their work, studying film and reading scouting reports, stretching and lifting weights. In between, in lieu of talking about the streak, they engage in the activity ballplayers do best.

They kill time.

The days blur into one long endless day, with three hours of baseball thrown in, before the players return to the clubhouse once again. At lockers to the left of Jobu, two players work out a fantasy football trade. The newly called-up rookies try to find the kitchen. Other guys pass the time with dominoes or cards. A hand of solitaire sits half-played on a table. Catcher Roberto Perez engages in an epic Mario Kart battle with one of the clubhouse attendants, known affectionately as clubbies. Perez screams and laughs -- "That was a good one" -- when he clips him at the finish to win. Perez's son, wearing his dad's number and eyeblack, toddles around the room. When he rounds a corner and sees his father sitting at his locker, the kid dashes across the room. They hold hands leaving the clubhouse.

The Indians win on Friday -- 16 in a row.

Decks of cards and cribbage boards are scattered around. Francona hosts a daily cribbage battle in his office, perhaps the only manager in baseball to play cards with his players. The Indians love the old-fashioned game, which is also wildly popular in the wardrooms of American submarines. That's fitting. A clubhouse really does feel a lot like living on a warship or a tour bus. The world moves past at a million miles an hour, but in the bubble, they're still and isolated. Little ever changes. Seventy years ago, Joe DiMaggio faithfully ordered half a cup of coffee from a Yankees clubbie; he did it his entire career, including the 19-game win streak he and his teammates ran off in 1947. There's not much difference between that world and the one the Indians occupy now. The ballplayer family lives by the same hand-me-down codes.

They win on Saturday: 17.

Rookie outfielder Greg Allen gets called up on Sept. 1 and meets the Indians in Detroit; he phones his father, who's been suffering from a bad back, and slips in the news. Allen smiles big and makes plans to send his parents the ball from his first hit. In his new life as a pro, he's stayed quiet, watching the veterans, trying to figure out the food chain and his place in it. On his second day in Cleveland, between wins 15 and 16, he politely asks a clubbie where he might park his car instead of paying the expensive daily valet rate at the hotel where he's staying.

"You can always leave it in the players' lot and walk over," the guy says.

"OK, OK," Allen says, thankful.

The winning streak is longer than his entire big league career.

Unless pressed, the Indians don't talk about the streak, at least while it's happening. Michael F. McElroy for ESPN

They win on Sunday: 18 and counting.

Joe Smith and Cody Allen arrange car rentals with the traveling secretary for an upcoming road trip to California; they plan to play golf on an off-day. Earlier, they bought two rodeo bucking bulls along with Bryan Shaw. Shaw goes online and buys a signed Ted Williams baseball. Now a steady stream of boxes arrives daily. Rising star Francisco Lindor buys everyone matching oversized blue plush robes with their name and number on the back. Pitcher Mike Clevinger gets himself an embroidered denim jacket like something found in a 1970s Laurel Canyon time capsule.

Josh Tomlin and Cody Allen wear matching ostrich skin cowboy boots.

"He bought his after mine," Cody says, defending himself.

They win on Monday: 19.

Tomlin and Smith argue about who throws harder. They crowd around a website called Baseball Savant. Smith points at a stat called perceived velocity.

"I'll dominate in that," he says.

"I bet you don't dominate me in that," Tomlin fires back.

They call up the fastest single pitch.

"I've thrown a pitch harder than you!" Tomlin says triumphantly. "That means I can throw harder than you!"

"Nononononono," Smith says.

"I gotta do some s---," Tomlin says, as they both laugh. "I ain't got time to Mickey Mouse bulls--- with you."

They win on Tuesday, No. 20, behind a shutout from ace Corey Kluber.

Kluber has a reputation as a baseball robot, but in the clubhouse, the hilarious Tomlin makes Kluber laugh, which might be why their lockers are side by side.

They consolidate two half-full Copenhagen cans into one. They try on shoes.

They drink lots and lots of Muscle Milk.

Andrew Miller pulls up the online security cameras from his home in Florida to monitor the damage from Hurricane Irma. He switches a television to the Weather Channel. He checks on his mother, who'd evacuated from the east coast of Florida to his house in Tampa, then evacuated again to Gainesville. As the storm closes in, he thinks about his World Series ring and his collection of jerseys in the house. Craig Breslow walks past and sees the images from Naples, where he lives, and recognizes the street in the shot, scarily close to his home. Miller worries about his ring.

"Where's yours?" he asks.

"Boston," Breslow says.

The Indians win Wednesday: No. 21, breaking the AL record.

Inside their underground home, on the lower level of the stadium -- LL on the elevator button -- they argue and encourage each other. At one point, closer Cody Allen leans over to congratulate starter Trevor Bauer. They've lived shoulder to shoulder for months. Bauer loves physics and advanced analytics, and Allen loves belt buckles and rodeo bulls. They couldn't be more different, but in this room they understand the most important things about each other. That's a clubhouse.

"Great job, Trevor," Allen says. "You were amazing."

They talk to their families on the phone. They work crossword puzzles. They talk packing philosophy for a long road trip.

"One pair of jeans," Allen says.

"One pair of jeans!?" Joe Smith says, laughing.

"I'm in 'em for two hours a day!" Allen replies.

The Indians win on Thursday, No. 22, the most consecutive wins in baseball history. (Only the 1916 New York Giants went more games without losing, 26, with one tie.) Afterward, they do what they've done all year. They check the schedule on the wall to find out what to do next. That's the nerve center of the clubhouse, the three dry-erase boards that tell the players where to be and when. Every day it lists stretching, batting practice, national anthem and first pitch, along with any special events. The schedule keeps them from drifting into the future or lingering in the past.

Yoga is at 2. Chapel is at 3:30. The barber is in.

Much to the delight of their fans, no team has won as many games in a row as the 2017 Cleveland Indians. Michael F. McElroy for ESPN

The Indians do all these things and more, but what they do not do, except under the duress of direct questioning, is talk about the streak, at least while it's happening.

"The mindset really isn't on the winning streak," Greg Allen says.

"We're not wrapped up in it," Kluber says.

"We're not talking about it as much as you guys are," Cody Allen says.

Everyone else certainly talks about it. Some analysts call it the most dominant stretch of baseball ever played. Led by Edwin Encarnacion and Carlos Santana, Cleveland hits more home runs than its opponents score runs. Kluber and Carlos Carrasco lead the pitching staff to an ERA under 2.00. Their run differential across the 22 wins is greater than their run differential for all of last season -- and that team won the pennant.

They sweep the Orioles and the Tigers.

They steadfastly say they aren't that concerned with the record.

"We haven't talked about it at all," Kluber says.

"We're playing good baseball," outfielder Jay Bruce says.

Ballplayers are always concerned about anything that might upset the delicate equilibrium they have constructed one routine day after another. Only the rare team can be like the 2017 Indians; nearly every other team would let the streak consume them, including last year's Indians. One of the players quotes a former Cleveland coach, Scott Radinsky, who pitched in the big leagues and fronted an underground but important punk band, a kind of free spirit who allows a clubhouse to function, to balance the prima donnas and the insane.

He always said he wanted to play with the kind of men he could lose with.

The same idea applies to winning.

"Success will mess with you," Bauer says. "Sometimes you get, 'I can skip this because I'm good.' It takes a lot of mental discipline to stick with it regardless of outcome."

The Indians say the streak brings lightness and air to the room. But they refuse to chase it, or revel in it, or pretend that it has its own meaning or value, other than getting them back to the postseason, where they came up one run short a year ago.

A streak brings attention and pressure, which continue to exist after the spark that creates it is extinguished. So they've spent six months in present tense, taking cues from their manager, who conducts 22 postgame news conferences while sidestepping and tap-dancing and refusing to say the streak carries any significance. "That's why Tito is so good at what he does," Allen says after a win, as Pitt and Penn State play on a television near his locker. "Regardless of if we won 10 in a row or lost eight in a row, he's the same guy."

As the son of a major leaguer, Terry Francona (far right) grew up in stadiums and feels most at ease among players. Rick Osentoski/USA TODAY Sports

Down the hall, Francona sits in his office behind a huge framed picture of himself as a child, in the Indians dugout with his dad. He is, perhaps more than anyone else in the game, a creation of this weird, subterranean clubhouse world. "I'm probably more comfortable here than I am anywhere," he says, gesturing around at the concrete walls. "I think I have an advantage because I grew up here."

Some of his earliest memories are from clubhouses.

His father, the original Tito Francona, played for nine teams, including six seasons with Cleveland. Young Terry once walked across a field before a game to shake Ted Williams' hand. "Mr. Williams," he said, "I'm Mr. Francona's son, and he wanted me to come over and say hello."

Williams grinned at the boy.

"Well, you are a great-looking kid!" he replied. "Now I want to know one thing, young man. Can you hit?"

Francona saw how his father's friends treated each other and the game, and every lesson he got about how a man behaved was taught by ballplayers. His humor, his ethics, his personal code -- all shaped inside a stadium. As an 11-year-old, Francona got to go with his dad on a three-city road trip, through Minnesota, Chicago and Kansas City, riding the planes and buses, hearing the dirty jokes and lining his pockets with free clubhouse candy. His mom sent him off with combed hair and a sport coat and got back a road-busted mess of a kid, who loved every minute.

"It was probably the 10 funnest days of my life," Francona says during the streak.

“Success will mess with you. Sometimes you get, 'I can skip this because I'm good.' It takes a lot of mental discipline to stick with it regardless of outcome.”

- Trevor BauerSo he's been happy these past weeks, not because he's managing a team into the history books but because he's been at a baseball stadium. Sitting in his office, which was exactly 68 degrees, he brings up something his old boss Theo Epstein once said about him. "He loves the game," Epstein told Boston Globe baseball writer Dan Shaughnessy. "He physically loves the clubhouse. Emotionally, I think he loves to let go of the outside world. Some people compartmentalize the job. Tito compartmentalizes the real world and throws himself into the clubhouse. He loves every aspect of the clubhouse."

Francona smiles at the insight.

"I remember when I read that," Francona says. "I was like, damn. I obviously know Theo was smart, but if I was going to be candid, that's pretty damned close. To me, this is probably my real world. I admit that."

The clubhouse cost him a marriage and his health, and he can't count the nights he's spent on a couch in a stadium, curled up beneath a blanket, alone. In his office in Cleveland, there's a red and blue Indians-colored afghan that clearly looks as if it's for more than decoration. Most days, he gets to his office early, not because he's a hard worker, he says, but because he feels at home. Watching a stadium wake up makes him happy. Sitting in an empty cathedral like Fenway or Wrigley calms him; the present and past combine, the things he sees and the things he remembers washing over him together. He liked the way the boards creaked at the old Yankee Stadium because Babe Ruth probably heard that same noise. Even now, he enjoys hotel lobbies, because he'd hang out there when visiting his dad on the road, giving his old man space to sleep in and get ready for the game.

He will, when asked, cop to at least one superstition.

There's a friend, whom he has nicknamed Gray Cloud, who's always brought bad luck.

"I will not talk to him," Francona says. "He is text only. He's cost me one job, he's not getting in the way again."

Simplicity is the primary goal when he's constructing his existence. In Boston, he even spent most seasons living in a hotel. For Francona, every day is the same, down to the number of water bottles he lines up in the dugout, and the hourlong swim he takes and the cribbage game he organizes. "I have a car here that I use about three times a year," he says. "I got a little moped. I take it everywhere downtown. I know all the police. It's Cleveland. After games, I'll go down the one-way and they're like, 'Hey, good game.'"

He points out his office door.

"It's parked right here in the hallway."

He played 10 seasons in the big leagues and jokes to his players about what a lousy career he had. But he played through severe injury and pain, a grinder who understands the hopes all players bring with them into the clubhouse. He understands doubt and fear and ego and swagger, and what internal problem each of those things is an attempt to solve. During the streak, as more reporters arrive every day in the small interview room to talk about the streak, he's more interested in finding out why the Browns released Pro Bowler Joe Haden, refusing to engage in record-chasing narratives, talking about how a season is fluid and how only today exists. He smiles and sighs when people keep asking questions, as if they think he's spinning them and not living by the codes he internalized as a boy.

Winning brings pressure, but Corey Kluber was at his robotic best during the streak. Michael F. McElroy for ESPN

The streak will mean nothing come October. A year ago, the Indians took 14 in a row, rolling through opponents, and they still came up a game short in the World Series. That Game 7 loss influenced many things about this season, including the 22 games the team just won. Kipnis, the clubhouse monk in charge of Jobu, took the World Series loss harder than most.

"A lot of things got smashed," he says.

He pauses a beat.

"I was one of them."

In the ninth inning of Game 7, he launched a ball down the right-field line that just went foul. Standing in front of his locker, he says he's watched that replay a lot. "Fraction of an inch," he says, then demonstrating with his hand the slight bat angle that would have changed their lives. His hand doesn't seem to move at all. It's a tiny difference. "The following month you're at home in your boxers eating pizza," he says, "and you're watching Rizzo and Bryant on late-night television and on SNL and you're like, the fork in the road."

When baseball people look at the Indians, other than wondering what kind of analytics the team uses to help its pitchers scout opponents, that is what they talk about. How did the team not let last year's close call derail this season before it even began?

That's Francona.

At the beginning of the season, the team did suffer from a hangover. Kluber says the starters were slow and sluggish. Kipnis says the games didn't seem to matter as much. Francona called a rare meeting early in the summer, feeling his team caught in the back draft of last season, not living day to day, breaking the code. The players say things turned around after that, and the winning streak is the clearest and most outward example. There are others.

Last year's streak took on meaning and affected the clubhouse dynamic in small but real ways. If the music wasn't on in the clubhouse, someone would say something. Winning changed the mood in the room, and by the time it ended in Toronto, that's all they could think about.

"That's been the most impressive thing about this streak," Bauer says. "You come to the field and it doesn't feel like we have a winning streak going. We had a streak last year, and the intensity ramped up and then it got to the point where it just caught up to us. This year it feels completely different."

Bauer's been watching Francona closely and thinks Tito's life growing up in clubhouses, and the decades of experience in them as an adult, has built up this almost sixth sense about the subtle interpersonal dynamics some managers don't even know exist.

"He's in tune with how this environment works," Bauer says. "He gets here, and something might seem off. Before anyone is even at the field, he's aware that something is off. Or something is on. Or something is different. He doesn't realize he's picking it up. It's just his sense for it. It's flow state. It occurs to him, and he doesn't even realize it."

No team has won as many games in a row as the 2017 Cleveland Indians, which is not how they want this season remembered. Last October left them longing to feel that joy and stress again, and they have almost made it through a long 183 days.

The streak ending is almost a relief because now the real business can begin.

The postseason is less than a month away.

"You're like ..." Kipnis says, and then he inhales deeply, like someone stepping out into the fresh air for the first time, "... we're back. You can see how we're playing. The team's been waiting for it. You see us getting close to it, and we're almost back there again."