The Official Coming-Out Party

For two decades, NBA ref Bill Kennedy was hiding in plain sight -- watched by millions but never truly seen. Then came the biggest game-changer of his life, the call he had to make.

Editor's note: This story contains explicit language.

Billy Kennedy doesn't look up from his scotch when he's presented with the microphone.

It's after midnight on a Friday in July at IronWorks, a restaurant and lounge that doubles as a clubhouse for a modest executive golf course in an older section of Glendale, Arizona, just blocks from Kennedy's home.

When Kennedy, a regular, checked in a few minutes ago, he inconspicuously slipped the karaoke wrangler $20 to jump the line. Now his song is up -- the intro led by a few sharp trumpet statements and hot brass chords. And as the horns give way to the piano and cool metal brushes against the drum, Kennedy begins to croon.

"A foggy day / In London town / Had me low / Had me down ..."

From the opening stanza, it's clear: This is not your typical late-night, booze-soaked aria. The man has pitch control, steady intonation, the kind of playful interpretation of an old standard popularized by Michael Buble that only a karaoke superstar can deliver. Several of the other 25 or so people left in the joint are straining to find the voice's owner. Their heads are on swivels. But Kennedy still hasn't lifted his eyes. His back is to the room, with its brass, wood paneling, NASCAR Sprint Cup Series banners, a whiteboard highlighting tonight's fish fry special and a video monitor for the lyrics -- something else he doesn't need.

"I viewed the morning with such alarm / The British Museum had lost its charm ... "

Those who accompany Kennedy around Phoenix, or on the road when he's officiating in the NBA's other 27 metro areas, say his karaoke camouflage routine isn't unusual. Sometimes he'll hide behind a pillar or stroll down a corridor away from the main singing area. "He's on a big stage often enough and doesn't need karaoke claps to make him happy," says Marc Davis, who dated Kennedy for two years after they met in 1999, before the two settled into a close 15-year friendship. "But throw a hot guy into the mix and then, yeah, he can be onstage in a heartbeat."

Twenty minutes later, as if on cue, an attractive young rodeo cowboy out of central casting is crushing Tom Petty's "I Won't Back Down." This is Dustin, and when he finishes, he ambles over to Kennedy. They've crossed paths on the Phoenix karaoke circuit before, but only recently did a friend tell him Kennedy's name and what he does for a living.

Like most referees at the big league level, Kennedy doesn't seek the spotlight, but it found him last December, when he publicly declared his sexual identity as a gay man a few days after the league suspended Rajon Rondo for calling Kennedy a "motherfucking faggot." Though NBA staff, fellow officials and numerous players and coaches have known for years that Kennedy is gay, the announcement instantly made him a public figure. Kennedy issued a brief statement on Dec. 13, telling Yahoo Sports, "I am proud to be an NBA referee, and I am proud to be a gay man. I am following in the footsteps of others who have self-identified in the hopes that will send a message to young men and women in sports that you must allow no one to make you feel ashamed of who you are."

For the next half an hour, Dustin and Kennedy get acquainted. And this kid with a thick drawl, a straw hat, a Western double-pocketed shirt, light tan boots and a belay with keys hanging from a jeans belt loop who just rode an actual bull at an actual rodeo for a solid 7.772 seconds before falling off? He tells Kennedy he was the best man at his gay cousin's wedding. And that statement of Kennedy's? It blew Dustin away.

"I'm so happy that you were proud of who you are," Dustin says. "So many people are hiding."

When Kennedy's next song is up -- "T-R-O-U-B-L-E," by Travis Tritt -- he's radiating light and seducing the crowd as Dustin cheers him on. Kennedy loves the attention from Dustin, this improbable ally. After the song is over, Dustin tells Kennedy he couldn't believe Rondo's one-game suspension was so short. He asks Kennedy how he got into officiating. He wants to know what Kobe is really like.

The karaoke wrangler brings Kennedy the microphone for his next and final number, "New York, New York." His chest voice, deep and rich, owns the room. And a crowd whose energy was waning before the microphone found its way to Kennedy has been drawn to the man who, just an hour ago, was invisible to them.

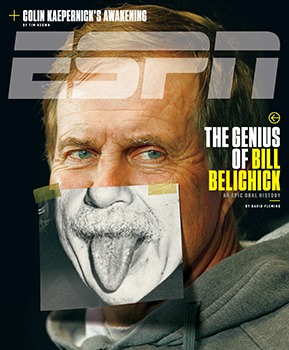

After Rajon Rondo berated NBA referee Bill Kennedy with an anti-gay slur during a game last season, Kennedy publicly revealed that he was gay. Kennedy talks about the fears he lived with as a closeted gay man and the reaction he received from the NBA.Matt York/AP Photo

FOR A MOMENT that stands as a watershed event in Kennedy's life -- and arguably in the history of gay people in professional sports -- the incident at the Palace of Auburn Hills is shrouded in mystery. Kennedy's recollection of dates is foggy, as are the impressions of others who were privy to the situation.

He'd been called up during the referee lockout of 1995-96 before landing a permanent position with the NBA in 1999. And during that time came an outing, of sorts, in the unlikeliest of ways. Kennedy remembers jogging through the tunnel as the final horn sounded after a Pistons game he had officiated. To protect the visiting team from any foreign objects hurled by fans overhead, a corps of ushers lined the tight passage. Kennedy saw a boy leaning over the rail for a handshake. He reached up to shake the kid's hand, bumping an usher as he did, then beelined to the officials' locker room.

As he arrived in Atlanta the following day for his next assignment, Kennedy remembers receiving a call from Rod Thorn, the NBA's executive vice president of basketball operations. The usher in question had charged that Kennedy inappropriately touched her. Kennedy says Thorn told him he was off the schedule until further notice. "I thought, 'I'm done,'" Kennedy says. "I had to buy my own ticket to get to Phoenix from Atlanta. I'm crying the whole flight home."

The NBA says Thorn doesn't have any memory of the incident, the investigation or any associated conversations. But a week later, having already missed six games, Kennedy says he was summoned to New York with the National Basketball Referees Association's general counsel, Howard Pearl, at his side.

Since his ascension to the NBA referee ranks, Kennedy had had a primary goal: to reach the five-year threshold, after which it would be more difficult for a referee to be fired. He knew that an internet rumor -- or even a news story -- on a gay NBA referee might not be a fireable offense, but the accompanying chatter was exactly the kind of attention he wanted to avoid. Now he was left with no other choice. "Before we talked, I said to Howard, 'Look. I just got to let you know: This is probably not possible between her and me,'" Kennedy says. "I said, 'It's just not compatible. We're just not compatible.'" Kennedy gave a telling nod. "[Pearl] looked at me and he went, 'Oh ... you're kidding.' And then he assured me I wasn't going to lose my job."

Pearl had Kennedy wait outside the conference room while he went in to brief the powers that be on his new finding: Billy Kennedy was not interested in inappropriately touching the female usher; Kennedy was a gay man.

Though the NBA could find no report on the Kennedy investigation in its offices or outside files, the league says the matter was put to rest. Kennedy says that nothing more was said about the situation. He had come out, had ostensibly broken through a barrier, and the NBA had shrugged.

"I was instructed," Kennedy says, "to get back on the floor and keep doing what I was doing before this happened."

Caitlin O'Hara for ESPN

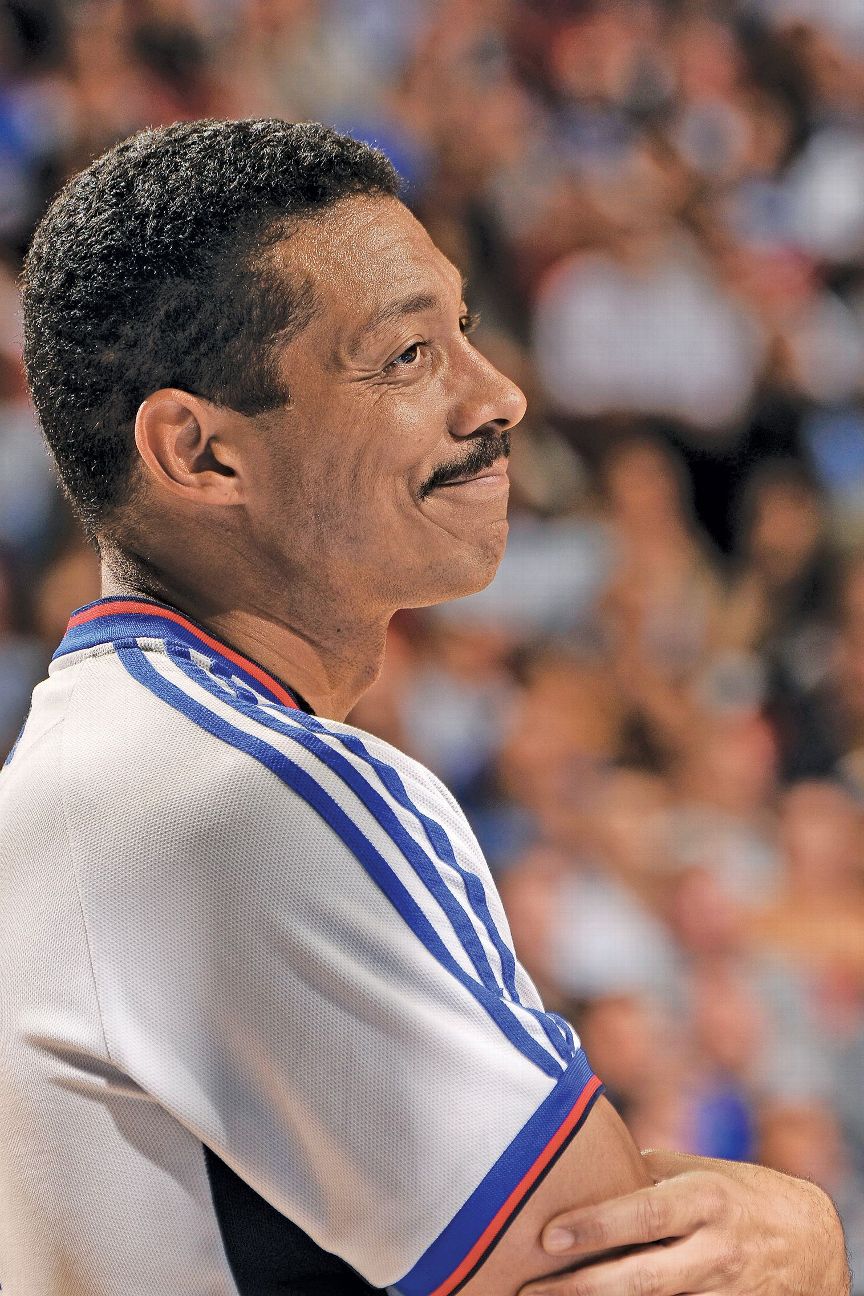

WHAT KENNEDY WAS doing was all he ever wanted to do. "Billy was unlike a lot of us," NBA referee Monty McCutchen says. "He knew when he was 10, 12 and 14 years old that he wanted to be an NBA ref."

In his early teen years in Phoenix, Kennedy would flip on the Suns' pregame radio broadcasts in the one-bedroom apartment he shared with his mother in the central city. If play-by-play man Al McCoy announced Tommy Nunez Sr. as one of the officials working the game, Kennedy would jump on his bicycle and zoom down to Veterans Memorial Coliseum in 15 minutes. There, a security guard named Mary Lou, charmed by a young Kennedy, would let him through the back gate.

Nunez, who refers to Kennedy as "my son," was a strong presence at the two most influential institutions in Kennedy's youth: the Boys & Girls Club and St. Mary's Catholic High School. With Kennedy's mother working multiple jobs to scrape together the money to send him to St. Mary's and Kennedy's father often absent from his life, the Boys & Girls Club was where Kennedy spent his time after school. And when, on a Saturday in 1978, the 8- and 9-year-olds at the club needed a referee, the 12-year-old Kennedy stepped in -- and a referee was born.

Kennedy quickly piled up assignments, and officiating soon became far more than a chance to earn five bucks; it was a compulsion. When he wasn't officiating games, he attached himself to Nunez. After Suns home games when Nunez was officiating, Kennedy would tag along with him and his officiating partner to the China Doll restaurant on 7th Avenue, where the crew would debrief its performance, talking shop until the place closed down after midnight. "He had an Afro and these big glasses and teeth," said Nunez's son Tommy Jr., a former NBA ref who often joined his father for dinner and is seven years older than Kennedy. "He'd come right over and he'd be sitting right there, this little kid, right in the middle of everything."

By the time he reached high school, Kennedy was a fixture in Phoenix's tight-knit referee community. By 17, Kennedy, after reffing a slate of high school basketball and football games on Friday nights, would wake early on Saturday mornings for a busy dance card of Pop Warner games. By 20, he was working the junior college circuit, signing up for virtually every officiating clinic in the western U.S. hosted by a big-name NBA referee and establishing himself as one of the best young officiating prospects in the Southwest. He was a kid in a hurry. "He was confident, he was brash, he was cocky," Nunez Jr. says. "Coaches didn't like him. He looked like a million dollars. He ran faster than anybody on the court, and he was very serious about what he did."

When the eagerly awaited call came from the Continental Basketball Association in 1992, it wasn't without complication. The league, Kennedy says, played on Wednesdays and Saturdays in cities that were rarely nonstops from Phoenix. To make it work, Kennedy landed a day job managing a local roller rink run by a benefactor in his circle of junior college officials, Bob Seitsema, who had a certain appreciation for the demands of getting to La Crosse, Wisconsin, from Phoenix. And though Kennedy had already worked as a customer service rep for America West Airlines, a microfiche filer and a bank teller, none of them tapped his inner referee like Great Skate.

"He just had this instinct about him where he was able to go and move around the building, as the manager, and spot trouble," Seitsema says of Kennedy, who would scan the roller rink for the girl who takes her drink out onto the floor, the guy hitting on someone else's girlfriend, the bully trying to hustle a smaller boy by the skate counter. "Billy would go into the DJ booth, and you had a little bit of an elevated look, and after about 10 or 15 minutes he'd say, 'See that guy over there in the red shirt? Keep an eye on him.' Sure enough, the red shirt, half an hour, 45 minutes later, the guy in the red shirt would be doing something."

Kennedy was still living with his mother in the family's two-bedroom apartment -- one he didn't move out of until he was 30 -- when she found a letter from a male friend of his that included some lurid sexual details. "The Letter led to The Talk," Kennedy says, adding that he's certain his mother knew he was gay before he did. After The Talk, he began to venture into gay spaces in his early 20s -- including Charlie's, a gay country bar a few blocks from where he went to grade school.

"It had the dark windows," Kennedy says. "We didn't officially know what it was, but I kind of knew what it was."

Like many gay men, Kennedy existed somewhere between the closet and daylight during his early adult years. "People suspected it because he's a good-looking dude, and you just didn't see him bringing girls to games," Nunez Jr. says. "You didn't hear him talking about a date, Mary Jane or whoever it might be." Around the time he joined the CBA, Kennedy started seeing men romantically. Though he wasn't out in Ref World, there was a tacit "don't ask, don't tell" policy between Kennedy and his friends, who operated under the assumption that he is gay. Getting to the NBA was difficult enough without walking any further than that into the light.

Because Kennedy's life is on the road, he lives in a model home in Glendale, Ariz., when he's not traveling. Caitlin O'Hara for ESPN

A 5-POUND BAG of Gold Medal flour (expires June 2006), Old El Paso hard taco shells (expires Dec. 28, 2004), multiple pouches of Kroger "Rice & Sauce," date and origin unknown. This is a sample of the inventory of the pantry inside Kennedy's four-bedroom, three-bath model home in the suburban Glendale subdivision that he moved into during the 1999-2000 season. All of it is left over from the staging of the house, as are the place settings glued to place mats, framed stock photos of white families, a sign over the rec room that reads KIDS ZONE (Kennedy is childless), flower arrangements and potted plants. "That ficus hasn't moved in 15 years," says NBA referee Scott Twardoski, a close friend.

The decor is such a source of amusement between Kennedy and his friends that maintaining the integrity of the model has become a badge of honor for him. Besides, an NBA referee's home is on the road. And so Kennedy, forced to disclose his sexual identity to the league office in New York to save his career, proceeded to spend the next 15 years going about the business of the bifurcated life of a gay referee.

"Being a professional official is kind of the perfect profession for avoiding," says Dale Scott, an MLB umpire who came out during the 2014 offseason and is one of Kennedy's close friends. "It is very conducive to it because you are constantly on the move. It's a built-in excuse you can use, which I did."

With his pedigree, Kennedy was the consummate insider, as at home in a referee's locker room or at a late postgame dinner as anyone on the league roster. Yet that comfort was predicated on a certain distance from co-workers, even those he counted as personal friends. "You say the right thing, and at the end of the day, as soon as we broke from dinner, I would go over there and they would go over there," Kennedy says. "You played the game -- it's learning how to survive."

“Being an official is perfect for avoiding. You're constantly on the move.”

- Dale Scott, an MLB umpire who came out in 2014

In Kennedy's mind, it was no real deprivation to stay in the closet on the court -- for a while, at least. He might not have declared himself openly gay, but when did referees publicly declare anything about themselves? They are the most visible, least known people in sports -- always present, never heard.

Then there was Mom, who died in 2011. "My mother didn't want me to come out," Kennedy says. "That's probably 75 percent of why I didn't come out earlier. I didn't want to disappoint her or upset her. I didn't want her to get phone calls from people or feel like she had to explain. And I didn't want any harm to come to me."

In 2002, Kennedy met a 25-year-old man in Washington, D.C., named Craig Glover who would move to Phoenix and date Kennedy for four years. When the NBA assigned Kennedy to officiate a regular-season game in Tokyo in the fall of 2003, he brought along Glover. "That's who he chose to bring, and even though it wasn't definitively stated, I think it's pretty neat," says McCutchen, who was also assigned to Tokyo and was traveling with his wife. "It shows a real confidence in Billy internally that even though he maybe wasn't ready to be out to the world, there was enough trust to share that with his co-workers. It's no small thing."

Back in Phoenix, Kennedy was a member of an extended circle of young, gay male professionals who socialized, played sports and traveled on weekend getaways together. Though he was on the road more than half the year, Kennedy very much resided at the center of the group. His home was frequently used as temporary housing for anyone in need. Dinner checks that never appeared at the table were often the result of Kennedy's quiet generosity. Yet as central as Kennedy's gay friends were to his life and he to theirs, he often went missing.

"Billy was the original ghoster," says Mike Fornelli, a close friend of Kennedy's who owns BS West, a popular gay club in Scottsdale, Arizona, that Kennedy has frequented and sung karaoke at for years. "Any time a camera would be around, Billy's gone. If there was somebody who knew somebody who knew somebody, Billy was gone. You always expect it. If you're going out with Billy, he might disappear."

In a collection of photos in Kennedy's home office sits a group shot of a softball team posing for the camera after winning a tournament. A dozen men joyously pose for a gay newspaper in Houston that was covering the event, but one of the subjects is obscured. He almost seems to be intentionally ducking out of view.

Friends from his officiating life unanimously say they either knew or suspected Kennedy is gay -- and didn't care. All the while, gay friends found his attempt to manage his persona entertaining, given that pegging Kennedy as gay might seem obvious to anyone with even a marginally tuned gaydar. "Billy, you don't want people to know you're gay," Fornelli would quip, "but your hands are on your hips all the fucking time."

When disgraced former NBA referee Tim Donaghy effectively outed Kennedy in 2010 by telling a radio host in Boston, "It's no secret on [the NBA officiating] staff that Bill Kennedy is a homosexual," Kennedy simultaneously became more relaxed about his sexual identity around people he knew yet more skittish about the possibility of it becoming public at a time when social media was exploding. "I was really concerned with if this got legs and took off, there could be some repercussions, whether it be player-wise, whether it be coaching-wise, whether it be public-wise," Kennedy says. "I had no idea, and so what I did was I just didn't do anything. I was like, 'Let's just be silent and see if this gains any traction.' And it never did."

Still, Kennedy embraced life as an openly gay man in the digital age. Off nights in NBA cities were spent at gay karaoke or country bars, maybe a steam house or flirting on Grindr. (Kennedy's profile photo is what's known in gay parlance as a "headless torso," from the waist to the neck.) He met his current on-again, off-again partner, Scott Fordham, at a karaoke bar in Toronto, where Fordham still lives. The two travel regularly on the road, where many NBA referees have spent time with the couple.

"I think he became more comfortable with it over time and he could hide in plain sight," Davis says. "It just wasn't as big a deal as it used to be. Once he realized that, he became gradually aware that the world wasn't going to stop spinning and he wasn't going to lose his job if he was completely out."

Rondo's disciplinary process took longer than expected because the player wasn't forthcoming about what he said and teammates in close proximity pleaded ignorance. ESPN

ON DEC. 3, moments after the final horn in Mexico City, Kennedy wasn't half as annoyed at Rajon Rondo for calling him a "motherfucking faggot" in the third quarter as he was at the damn Wi-Fi in the referees' locker room at Arena Ciudad de Mexico.

An incident like the one involving Rondo and Kennedy triggers an "atypical report" from each of the game officials, a detailed account of what transpired from their individual perspectives, in addition to the regular game report, both of which needed to be emailed off to New York. With the Wi-Fi not cooperating at the arena, Kennedy, Bennie Adams and Ben Taylor worked on an outline of both reports that they'd finish back at the St. Regis hotel. As the crew chief, Kennedy was responsible for pulling them together, and with a flight before dawn, he needed to hustle.

As the group sat in the locker room enumerating every detail from the incident that warranted inclusion in their account, Adams noticed Kennedy's brain was churning. Though he was measured and as committed to process as ever, Kennedy was beginning to consider the enormity of what had happened on the court. After Kennedy had whistled Rondo's Kings teammate DeMarcus Cousins for a foul on Jae Crowder, Rondo had badgered Kennedy. "That's not a fucking foul," he'd barked at Kennedy twice. When Rondo persisted, Kennedy assessed him a second technical and an ejection, after which Rondo stalked Kennedy, yelling after him, "You're a motherfucking faggot. You're a faggot, Billy," according to the league's report.

"Billy was stunned that those were words that were used in 2015," Adams says. "As the night wore on, you could see him reflecting and thinking. As he's writing the report, he's like, 'It's time that I come out and stand up.'"

The next several hours -- at the arena, then later at the hotel -- passed in fits and starts. The referees recounted details, wrote copy, waited for Wi-Fi (the hotel rooms were experiencing intermittent outages, so the crew congregated down in the lobby), all the while listening to Kennedy weigh the potential magnitude of coming out publicly should he choose to. "Over the course of the night between the locker room, the hotel lobby as we were writing our report, you could see the process, the conversation he was having," Adams says. "'This is it for me. ... It's not OK for this to happen to people in the workplace or anywhere else. ... And I'm going to say something about it.'"

By the time the crew finished its paperwork, it was 3 a.m. Kennedy headed to the airport as the league immediately went to work, setting up phone interviews with the officials and players involved.

When he arrived in Miami, Kennedy received a call from Mike Bantom, the league's executive vice president of referee operations, and Kiki VanDeWeghe, executive vice president of basketball operations, both of whom had read the report and were horrified. The National Basketball Referees Association's general counsel, Lee Seham, also got in touch to discuss with Kennedy a more nuanced point: Players who have yelled anti-gay epithets at officials, as Kobe Bryant did at Adams in 2011, were typically hit with a fine ($100,000 in Bryant's case) but no suspension. Adams isn't gay, therefore the "faggot" hurled in his direction is regarded as offensive and inexcusable, but not hate speech. And for a league that relies on precedent when rendering verdicts, this complicated the process. Using "faggot" as a general schoolyard taunt against a heterosexual official isn't the same offense as attacking a gay official with "faggot," but treating Rondo's behavior as hate speech would essentially out Kennedy.

Asked this summer whether they were aware Kennedy is gay, a number of players and coaches characterized Kennedy's sexual identity as an open secret. But did Rondo know? A source close to the league's investigation says that Rondo was asked by Elizabeth Maringer, the NBA's vice president and assistant general counsel who led the investigation, whether he knew Kennedy was gay when the incident occurred. Rondo replied that he didn't.

The onus, then, was on Kennedy to disclose his true identity, lest the incident be treated as just another case of an NBA player hurling anti-gay language as a proxy for asshole. "I had to take it to the next level in order for this issue to be taken up in a different court of appeal, in a different area to where people can say, 'This is not right,'" he says. "I knew that this was going to happen when he said it on the floor. I knew."

HOURS AFTER THEY worked the Heat game together, Kennedy and Twardoski sat at dinner, discussing the ramifications of Kennedy's decision, then, naturally, moved on to a karaoke bar. Kennedy had mentored Twardoski, spending hours on the phone breaking down Twardoski's game film for areas of improvement. Years earlier, before Twardoski entered the NBA, he'd spent a summer at Kennedy's home in Phoenix. Every day, they'd follow a similar regimen -- the gym, lunch at Panda Express, an afternoon nap, talk shop, dinner, karaoke, then come home at 2 a.m. to break down film for four hours before going to bed at dawn.

One night in 2002, a group of referees was hanging out in a hotel suite in Mesa during a referees camp when Kennedy told Twardoski he needed to discuss something with him. Twardoski followed him out to the elevator bank, where Kennedy pointedly asked him whether there was anything specific he wanted to talk about.

“I don't think it was fair for him to say what he said and only get one game.”

- Bill Kennedy on his confrontation with Rajon Rondo

"I said, 'Not really. I don't know what you're talking about,'" Twardoski says. "Billy goes, 'Well, right now is there anything you ever wanted to ask me? Here's the time to ask me.' I said, 'You know what, Billy, I don't have anything to ask. There's nothing I need to know unless you want to tell me something.' Billy basically said, 'I want to come out.' He was in tears, and he kept looking at me, and I said, 'And ...?' He said, 'What do you mean, "and ... ?"' I said, 'Billy, that doesn't change anything.'"

Now, 13 years later, Kennedy wanted to vent. The situation was frustrating, largely because it was being adjudicated outside of his control. Kennedy speculated about potential fallout and wondered whether he'd have to go in front of the media to make an announcement. He asked Twardoski whether he'd be at the news conference if that were the case. (Kennedy ultimately didn't do so.)

As the investigation moved into the next week, Kennedy grew both more frustrated and defiant. The process was taking longer than anticipated because Rondo wasn't forthcoming about what he said and, as is often the case in NBA disciplinary investigations, teammates in close proximity pleaded ignorance. In addition, the league didn't have the full broadcast complement it typically has because the game was played in Mexico City. The league hired an audiologist to confirm the officials' account of what was said.

Six nights after the game, Kennedy and his friend Davis went to see A Christmas Carol: The Musical at a dinner theater in Phoenix.

"When we first sat down, he goes, 'This Mexico City thing isn't going away,'" Davis says. "I could tell there was some hesitancy, some insecurity just because of the volume that I knew he was going to generate in conversation, but there was also a comfort level that I had not experienced with him prior. On one hand, yeah, he might have felt like he had the weight of the world on his shoulders. But at the same time, he knew now was the time, and now was a more comfortable world to live in. I think he identified that but still felt like it was a big deal."

Scott, who officially came out in Outsports during baseball's offseason in December 2014, was an important sounding board for Kennedy, who liked that template for his own announcement. Kennedy says that, left to his own devices, he suspects he would've come out in a similar fashion in the near future. In past years, the two used to joke that they'd make a joint announcement on Ellen.

"It bothered him because it was so incredibly disrespectful and wrong," Scott says. "I think that's what really spurred him to say, 'Screw this. This is not right, and I'm going to do something about it. I'm going to make a statement. I'm going to say, "You know what? This was not only wrong in the context of official-player relationship, as far as getting ejected or getting T'd up or whatever. This was wrong on a personal level. This is wrong, and in this day and age, it's not going to be tolerated." ' "

Finally on Friday, Dec. 11, eight days after the Mexico City incident, the NBA issued its verdict -- Rondo would be suspended one game. "The totality of all those issues -- trying to take into account Bill's privacy, due process for Rondo, a potential appeal and the fact that we'd never had a disciplinary issue where what was said wasn't definitively picked up by a microphone -- that's how we got to a one-game suspension in this case," NBA commissioner Adam Silver says now.

The referees' union felt the sentence was too lenient and took issue with the notion that Silver had an imperative to protect Kennedy's privacy at the expense of a more severe sentence. "We had every step of the way during the investigation said, 'Billy is gay. It is generally known that he is gay, and we are asking that this case not be treated in the context of the prior incidents involving the use of comparable language. It must be treated differently because he is gay,'" Lee Seham says.

Kennedy received a call from Silver the weekend after the Friday verdict. Silver explained the league's rationale in issuing a one-game suspension; he knew of Kennedy's sexual identity, although the two men had never had a previous conversation about it. As such, Silver wanted to balance that knowledge with discretion.

Kennedy thanked Silver for his judiciousness, adding that as someone who makes judgment calls for a living, he understood how painstaking the process could be. Though he didn't mention it to Silver in that phone call, Kennedy was preparing to go public with his announcement in short order. "I didn't think it was fair that this individual was going to say what he said and only get suspended one game," Kennedy says. "I didn't think the character of him, or his character at that moment, was worth just the one-game suspension, and it had to be brought out. The only other way to bring it out was if I went public to bring attention to what actually happened. I wanted everyone to know the facts."

Kennedy coordinated a statement through Seham. Three days after the NBA's verdict, the statement was published on Yahoo Sports.

Kennedy was assigned to one additional Kings game after the incident, but Rondo wasn't in attendance. Three days after the incident, Rondo tweeted, "My actions during the game were out of frustration and emotion, period! They absolutely do not reflect my feelings toward the LGBT community. I did not mean to offend or disrespect anyone." He has not, to this day, reached out to Kennedy directly. He declined to comment for this story.

As a boy, Kennedy would make every effort to learn from NBA refs. Now he teaches them. Fernando Medina/NBAE/Getty Images

THE NIGHT IN 2002 that Kennedy came out to Twardoski, he told Twardoski that were anything ever to happen to him -- a fatal accident or unnatural death -- he wanted Twardoski to tell everyone in attendance at the funeral the true Billy Kennedy story, one featuring a gay man who made it to the NBA as a referee. "When the Rondo situation happened, Billy said jokingly, 'Well, you're off the hook, but I still need you to speak at my funeral,'" Twardoski says. "That's how important it was for him to be able to tell the story when it needed to be."

No more than eight hours after Kennedy began to share that story to the world, he suited up for a Spurs home game against the Jazz. The day had been a whirlwind. His statement had been released that morning, and immediately his phone had begun to convulse with calls and texts. "I put it on silent because I couldn't keep up," Kennedy says. "There were too many text messages, too many things going on, and I have to work that day."

The morning meeting provided a little distraction, but the story was now being broadcast nationally, and it was gaining traction. For good measure, the league dispatched a security specialist and a public relations staffer to San Antonio. Before the game, Spurs coach Gregg Popovich was asked whether he was surprised by Rondo's slurs.

"Why would I be surprised?" Popovich told the pregame media scrum. "You see it all the time. It's unfortunate. It's disgusting. Bill is a great guy. He's been a class act on and off the court. And as far as anybody's sexual orientation, it's nobody's business. It just shows ignorance to act in a derogatory way toward anybody in the LGBT community. Just doesn't make sense."

Popovich's comments came out of Kennedy's earshot, and Kennedy found himself in an unusual state -- terrified of taking the court. He told the public relations staffer he didn't want to take any questions from reporters. He merely wanted to work the game, then return to the hotel.

With 16 minutes remaining before player introductions, Kennedy left the officials' locker room and marched down the dank concrete corridor in the bowels of the AT&T Center. On his way to the floor, he spotted Spurs general manager R.C. Buford walking the other way.

"[R.C.] looked at me and he goes, 'You OK?'" Kennedy says. "I gave him a hug for like 30 seconds. I was late to the floor because of it. I almost started to cry. I was emotional, and I didn't know what the hell was going to happen. We didn't say a word to each other. Other than I looked at him and I said, 'Thank you.'"

There's little in the universe more familiar to Kennedy than the final 15 minutes of warm-ups in an NBA arena before the horn sounds -- the thumping music, players running through their shooting and stretching rituals, the crowd growing more anticipatory. But for Kennedy that night, the scene was a blur. He faintly remembers chatting with Sean Wright, who was also working the game. Jazz forward Trevor Booker approached to say, "Much respect to you," but the rest of it was all fog and nerves.

As the lights went down for player introductions, Popovich sidled up beside him -- telling Kennedy that he chose to walk over in the dark because he didn't want to make a scene that everyone could witness. "He said, quote, unquote, 'You have more guts, you have more balls than anybody I know,'" Kennedy says. "'You have more courage than anybody I know. Now, go out there and kick ass.' Then he walked away. He didn't say a word to me for the rest of the game."

Kennedy is a man who takes comfort in routine -- from his favorite karaoke haunts to the constancy of the NBA rulebook. Caitlin O'Hara for ESPN

ON A SUNDAY in late June, Kennedy's eyes take a long tracking shot of a procession of drag queens in tiaras as they strut down Fifth Avenue in the LGBT Pride March in New York. "I couldn't do that," he says to Fordham, who has joined him for the weekend's festivities. "Oh, lord. Look at that one," he says about a 6-foot-4 queen with a long, flowing blue dress, a bare chest and black platform pumps.

For all the rites of passage Kennedy practiced as a semi-out gay man over the past two decades, marching in a gay pride parade had always presented a degree of difficulty too high.

"I was always concerned about who might see me, how being seen in a situation like this would affect me and affect my job," Kennedy says as he makes his way toward Fifth Avenue to check out the festivities. "I was always concerned about not doing anything to jeopardize the NBA or myself or put anybody in that kind of jeopardy."

For gay men like Kennedy, even in 2016, the fear of consequence is real. Whatever signals one might glean from polling numbers, prestige television or a popular Facebook post circulating among his peers, Kennedy has grown up in a world where a gay man doesn't know how people are going to react when they learn he sleeps with men. Now, unless another player or official makes a similar announcement sometime soon, Kennedy will be the only openly gay man to appear on an NBA court this October when the league tips off its season.

He is a man who fears the unknown. He takes his dinner at the same casual-dining chain restaurant every single night near his home in Glendale, rotating among three dishes. He bought a model home because "I knew what I was getting." Ask what frightened him the most pregame that night in San Antonio, and he tersely answers, "the unknown."

But it's June 2016, and that anxiety is waning. One year ago, the U.S. Supreme Court sanctioned gay marriage nationally. Now virtually every NBA team performs at least token outreach to lesbians and gays in its market, and the league has made pro-gay messaging a point of emphasis. Pride parades used to be headlined by Dykes on Bikes. On this day, the NBA is preparing its float on 37th Street opposite a thumping T-Mobile float.

The NBA's float is the first for a pro sports league in a gay pride parade, and Silver, in accompanying it, will set another first. For Kennedy, these facts seem to hold profound meaning. He's a company man at heart, and for as long as he can remember, "NBA official" has been the most important identity marker in his life. The several dozen NBA employees and family members, the referees who wished him good luck before his trip to New York -- these are every bit as much his people as the boys back in Phoenix. The league is Kennedy's lifeblood, and on this day, goddamn, the league is sending Jerry West's silhouette cruising down Fifth Avenue through a canyon of dancing shirtless twinks, PFLAG moms, queer college kids and an army of nice, cosmopolitan straight New Yorkers who will cheer and wave at Kennedy as he dances atop the float.

"If you would have told me when I first started out that the NBA would have a float in the frickin' Gay Pride parade, in New York, I would have laughed at you," says Scott, the gay major league umpire. "And so would Billy. He didn't see this happening 10 years ago. Let alone five years ago."

Though multiple league sources confirm Silver was a full-throated supporter of the league being a strong presence at Pride, it didn't come without some apprehension. "If you had asked me going in, I would've said, 'I think it's going to be 70 percent positive,'" Silver would later say. "We weren't looking for PR, and we didn't alert the media. But it was 100 percent positive, and that's setting aside the public relations aspect. I didn't understand how important symbolically the event was for my co-workers until that afternoon."

Now, as the NBA float turns the corner left onto Fifth Avenue, "Empire State of Mind" booming from the speakers, Kennedy breaks out in dance. Then he spots Silver among the large NBA contingent that's on foot surrounding the float. Kennedy jumps off the moving float, runs to Silver and captures him with a fierce, tight hug.

When he's done with Silver, Kennedy sprints over to the throngs of onlookers lining the sidewalks of Fifth Avenue and works the crowd like a candidate working a rope line. He slaps hands, then runs a couple of laps around the float before jumping back onto the float -- a sequence that will be repeated several times over the next two hours.

A few minutes later, Kennedy is dancing with Silver, who's joined the staff on the float. Silver, wearing baggy cargo pants and an #OrlandoUnited shirt to commemorate the massacre at the Orlando gay club, pulses to the music as best he can. He waves a small rainbow flag. "It's important that he be here," Kennedy says above the din. "It makes an employee feel comfortable. It makes an employee feel that it is safe, to know that you've got our back. If we want to be who we are, you've got our back."

Later, as the float crosses Bleecker Street, Kennedy grinds with Fordham with little inhibition. The commissioner of his league is standing 10 feet away with his own dance stylings -- one part head bob, one part shallow squat. Nobody is self-conscious, and Kennedy's appetite for the scene is insatiable. With one hand on Fordham's hips, Kennedy reaches the other into his pocket to pull out his phone. He struts up to the bow of the float, where he holds up the phone to capture the full breadth of the day.

Above the deafening music, he says, "It feels good not to be invisible."