No More Questions

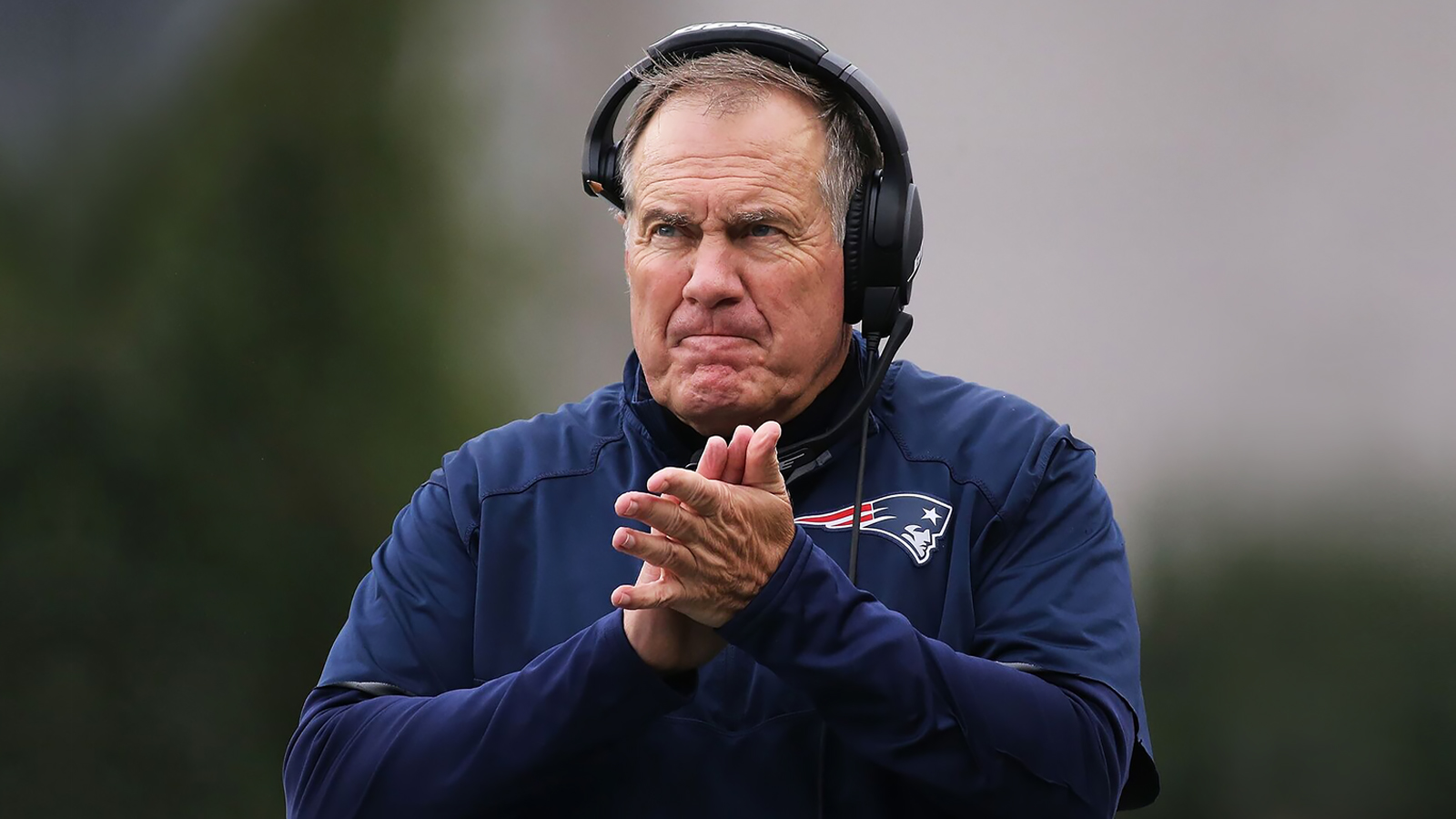

Call Bill Belichick what you want, but these accounts of his uncompromising life -- from prodigy to professional ballbuster -- reveal why history might one day call him the greatest.

Editor's note: This story on Bill Belichick was originally published on Oct. 4, 2016. Belichick turns 68 on Thursday.

e went by Billy at his first NFL job.

It was 1975. He was 23, a failed college football lineman, and the Baltimore Colts agreed to hire Billy Belichick as a glorified gofer. Since then, he has been called just about everything in the book. At his next stops, in Detroit and Denver, Belichick's mental mastery of the game -- and brash approach -- earned him the labels Boy Genius and Punk. In New York, Bill Parcells nicknamed him Doom and Gloom, mocking him for his abrasive demeanor and reluctant, monotone delivery. In the 1990s, he was known as a lame duck at the end of a few mostly miserable years in Cleveland. And in 1999, after serving as Jets coach for less than a day, he referred to himself as HC of the NYJ on a handwritten resignation note.

During the past 16-plus seasons in New England, he has won 13 division titles -- including a record seven in a row -- 23 postseason wins (most by an NFL head coach), six AFC championship games and four Super Bowls. These days, people call him Genius, Misanthrope and even Hoodie. After Spygate, Hall of Fame coach Don Shula tagged him Beli-cheat. To his friends, he is often just A--hole, which, tellingly, Belichick considers a term of endearment.

But after all this time, and all these attempts to label him, does anyone really know Bill Belichick? ESPN's NFL Nation and The Mag teamed up to crack the greatest enigma in sports. The resulting interviews, with coaches, players and other associates, provide the definitive character study, covering Belichick's genius, failures, partnership with Tom Brady, the pathologies around his controversies and the ultimate debate about his legacy.

David Fleming spotlights the rules and methods that have helped Bill Belichick become, perhaps, the greatest coach in NFL history.

Seeds of Genius

Bill Belichick was a coaching vagabond before he could walk. Soon after Bill's birth, in Nashville, Tennessee, on April 16, 1952, his father, Steve, was fired, along with the rest of the Vanderbilt football staff. It was a harsh lesson about the fleeting nature of the profession and one that has remained with Bill his entire life, according to the late author and his longtime friend David Halberstam.

After a two-year stop at North Carolina, where the coaching staff was again fired, Steve eventually enjoyed a long and renowned career as a scout and professor at the Naval Academy. Bill's mom, Jeannette, was also a teacher and by all accounts a lovely, loquacious woman who spoke seven languages and enjoyed a lifetime subscription to The New Yorker. It was in Annapolis where, after recognizing his son's physical limitations (the scouting term he used to describe Billy was "heavy ankles"), Steve began teaching him how to apply his considerable intellect to football. He'd carry those lessons to Wesleyan University, where he played football, lacrosse and squash and majored in economics.

Phil Savage (Browns Assistant, Scout, 1991-95): "His dad would take Bill to work when Bill was 9 or 10. Things would get busy and Bill would end up in a room or a closet by himself with a projector and a stack of film, and it's like, 'Son, take these tapes and tell me how many times they ran split back.' And Bill just devoured it. He always saw video and film and the mental side of the game as the great equalizer for him."

Phil Savage (Browns Assistant, Scout, 1991-95): "His dad would take Bill to work when Bill was 9 or 10. Things would get busy and Bill would end up in a room or a closet by himself with a projector and a stack of film, and it's like, 'Son, take these tapes and tell me how many times they ran split back.' And Bill just devoured it. He always saw video and film and the mental side of the game as the great equalizer for him."

Bill Parcells (Giants Hall of Fame Head Coach, 1983-90): "Bill lived this game his whole life. Growing up with football in your life, that experience as a young man at the dinner table, is invaluable. He was educated to the nuances of the sport at a very young age. By the time he got his first job, he already had experience just from living it with his dad. I think that's where the foundation was."

Bill Parcells (Giants Hall of Fame Head Coach, 1983-90): "Bill lived this game his whole life. Growing up with football in your life, that experience as a young man at the dinner table, is invaluable. He was educated to the nuances of the sport at a very young age. By the time he got his first job, he already had experience just from living it with his dad. I think that's where the foundation was."

Former NFL Head Coach: "Bill likes creating the image of an outlaw, the tough guy. I think he really relishes it. But who is he really? He was kind of a geeky kid. Not that athletic. A failed football player."

Dick Miller (Professor Emeritus of Economics, Wesleyan University): "He was well-prepared, very focused and intense, and he looked in class then very much like he looks on the sidelines now, just with bigger girth and less hair. I don't know what would separate him from other coaches, but it certainly wasn't playing experience in college. He was not a starter as a sophomore, he didn't play as a junior and when he was a senior, a freshman took his spot. But he was always regarded as a coach on the field, especially in lacrosse. Other players, if they didn't know what the play was about, they'd ask Bill before they'd ask the coach."

Dick Miller (Professor Emeritus of Economics, Wesleyan University): "He was well-prepared, very focused and intense, and he looked in class then very much like he looks on the sidelines now, just with bigger girth and less hair. I don't know what would separate him from other coaches, but it certainly wasn't playing experience in college. He was not a starter as a sophomore, he didn't play as a junior and when he was a senior, a freshman took his spot. But he was always regarded as a coach on the field, especially in lacrosse. Other players, if they didn't know what the play was about, they'd ask Bill before they'd ask the coach."

Getty Images

To The Extreme

After Wesleyan, Bill was hired by the Colts for $25 a week and a room at the Howard Johnson's. His responsibilities grew quickly, thanks to scouting skills that were so impressive, players said it was like having a spy working for the Colts. The next season, according to Halberstam's book "The Education of a Coach," Belichick jumped to Detroit, where he earned $10,000, a brand-new Ford (a loaner, it turns out) and a perfect score on a playbook pop quiz given to all coaching candidates. After a stint in Denver, Belichick spent the next 12 seasons in New York (11 with Parcells), six as defensive coordinator. During that time, the Giants won two Super Bowls.

Bill Parcells: "With the Giants, we were trying to take away an opponent's best players and not let them beat us. Bill has followed suit on that pretty much his whole career."

Bill Parcells: "With the Giants, we were trying to take away an opponent's best players and not let them beat us. Bill has followed suit on that pretty much his whole career."

Rick Venturi (Browns Assistant, Scout, 1991-95): "Everybody in football wants to take away what you do best. The difference is Bill would go to an extreme to make you play left-handed. That's Belichick's absolute genius: pragmatism. When other coaches say it's important that we take away an opponent's best receiver, only Bill would commit four defenders on a receiver and play the rest of his defense with the other seven."

Rick Venturi (Browns Assistant, Scout, 1991-95): "Everybody in football wants to take away what you do best. The difference is Bill would go to an extreme to make you play left-handed. That's Belichick's absolute genius: pragmatism. When other coaches say it's important that we take away an opponent's best receiver, only Bill would commit four defenders on a receiver and play the rest of his defense with the other seven."

Mike Munchak (Hall of Fame Guard and Coach, Oilers/Titans, 1982-2013): "You'll go into a game, and say you're a great run-stopping team, Bill would respond with, 'We don't care about averages, we're going to switch it up and throw the ball 60 times.' Next week, they might go the other way and hand the ball off 40 times. He's willing to do whatever."

Mike Munchak (Hall of Fame Guard and Coach, Oilers/Titans, 1982-2013): "You'll go into a game, and say you're a great run-stopping team, Bill would respond with, 'We don't care about averages, we're going to switch it up and throw the ball 60 times.' Next week, they might go the other way and hand the ball off 40 times. He's willing to do whatever."

Rick Venturi: "Early in the week, before the X's and O's, you meet for hours upon hours as a staff breaking down personnel to come up with a game plan. Once Bill decided what to focus on taking away, he always ended that meeting with the same saying: 'And I don't want to have this discussion on Sunday.' Basically, he was saying, 'This week, not letting their No. 1 receiver catch any balls is one of our Ten Commandments, and no one better break it.'"

Rick Venturi: "Early in the week, before the X's and O's, you meet for hours upon hours as a staff breaking down personnel to come up with a game plan. Once Bill decided what to focus on taking away, he always ended that meeting with the same saying: 'And I don't want to have this discussion on Sunday.' Basically, he was saying, 'This week, not letting their No. 1 receiver catch any balls is one of our Ten Commandments, and no one better break it.'"

Curtis Martin (Hall of Fame Running Back For the Patriots, 1995-97, and Jets 1998-2006): "We were at a lunch table, and Jimmy Hitchcock and Ty Law were raving about Belichick when he was an assistant under Parcells. 'He's on another level,' they said. 'He's just a freakin' genius, this dude. I'm telling you, he's going to win a Super Bowl someday.' They were in awe of his football knowledge. You could tell by the way they were communicating it, so passionately, they felt he gave them such an advantage. In their eyes, Belichick was playing a very strategic, intricate game of chess while everybody else was playing checkers."

Curtis Martin (Hall of Fame Running Back For the Patriots, 1995-97, and Jets 1998-2006): "We were at a lunch table, and Jimmy Hitchcock and Ty Law were raving about Belichick when he was an assistant under Parcells. 'He's on another level,' they said. 'He's just a freakin' genius, this dude. I'm telling you, he's going to win a Super Bowl someday.' They were in awe of his football knowledge. You could tell by the way they were communicating it, so passionately, they felt he gave them such an advantage. In their eyes, Belichick was playing a very strategic, intricate game of chess while everybody else was playing checkers."

"Bill lived this game his whole life," says former Giants coach (and Belichick boss) Bill Parcells. James D. Smith/Icon Sportswire/Newscom

The Discomfort Zone

On Feb. 5, 1991, nine days after the Giants' 20-19 victory over the Bills in Super Bowl XXV, Belichick was named head coach of the Browns.

Rick Venturi: "Bill had come into Cleveland as the most sought-after assistant in the league, the fair-haired savior of the Browns."

Rick Venturi: "Bill had come into Cleveland as the most sought-after assistant in the league, the fair-haired savior of the Browns."

Phil Savage: "I met Bill at the very beginning of his head-coaching career and on my very first day in the NFL. On Monday, March 18, 1991, I walked into the Browns' building, shook his hand, and Bill says, 'What are we paying you again?' I said $20,000. And he goes, 'Look, we had planned on hiring two guys, but I want you to do both sides of the ball. We'll give you an extra five grand, and eventually we'll bring some other a--hole in to help you out.' That's my first interaction with Bill. I'm like, 'Uh, thanks for the opportunity.' Six months go by with no help, and I was like, 'I'll give you your $5,000 back.' I had just come from UCLA, working for Homer Smith, one of the true gentlemen in this business. Then, all of a sudden, I end up with Bill Belichick. For a year I don't think I managed to do anything right."

Phil Savage: "I met Bill at the very beginning of his head-coaching career and on my very first day in the NFL. On Monday, March 18, 1991, I walked into the Browns' building, shook his hand, and Bill says, 'What are we paying you again?' I said $20,000. And he goes, 'Look, we had planned on hiring two guys, but I want you to do both sides of the ball. We'll give you an extra five grand, and eventually we'll bring some other a--hole in to help you out.' That's my first interaction with Bill. I'm like, 'Uh, thanks for the opportunity.' Six months go by with no help, and I was like, 'I'll give you your $5,000 back.' I had just come from UCLA, working for Homer Smith, one of the true gentlemen in this business. Then, all of a sudden, I end up with Bill Belichick. For a year I don't think I managed to do anything right."

Kirk Ferentz (Browns Assistant, 1993-95): "One of my first experiences was the interview, how extremely uncomfortable it was. You've seen him in press conferences. No matter what I said, there was a real poker face there. I mean, I was not getting any feedback. I was dying a thousand deaths, especially in our first visit, which happened the first night I got there. That was hard, and then I got sent back to Maine. Didn't think I had a chance at all. A mutual friend talked to him over the weekend. He called me back and said, "No, he liked you." I was like, "Oh my god. That's a funny way to show it." It was uncomfortable."

Kirk Ferentz (Browns Assistant, 1993-95): "One of my first experiences was the interview, how extremely uncomfortable it was. You've seen him in press conferences. No matter what I said, there was a real poker face there. I mean, I was not getting any feedback. I was dying a thousand deaths, especially in our first visit, which happened the first night I got there. That was hard, and then I got sent back to Maine. Didn't think I had a chance at all. A mutual friend talked to him over the weekend. He called me back and said, "No, he liked you." I was like, "Oh my god. That's a funny way to show it." It was uncomfortable."

Curtis Martin: "I grew up in a tough neighborhood. It was never the guy who was talking tough that you feared or thought twice about. It's the guy like Bill who's very quiet and didn't have much to say. Back in my neighborhood, they say the loudest one in the room is the weakest one in the room. Belichick had that kind of factor to him, that quiet storm -- quiet but powerful, almost like demanding your respect without saying too much."

Curtis Martin: "I grew up in a tough neighborhood. It was never the guy who was talking tough that you feared or thought twice about. It's the guy like Bill who's very quiet and didn't have much to say. Back in my neighborhood, they say the loudest one in the room is the weakest one in the room. Belichick had that kind of factor to him, that quiet storm -- quiet but powerful, almost like demanding your respect without saying too much."

Jim Schwartz (Browns Assistant, Scout, 1993-95): "The staff in Cleveland was full of superstars: Nick Saban, Scott O'Brien, Kirk Ferentz. I had no family. I had no bills. I basically lived at the Browns' office. It was a great chance to get an education, to get a Ph.D. in football."

Jim Schwartz (Browns Assistant, Scout, 1993-95): "The staff in Cleveland was full of superstars: Nick Saban, Scott O'Brien, Kirk Ferentz. I had no family. I had no bills. I basically lived at the Browns' office. It was a great chance to get an education, to get a Ph.D. in football."

Phil Savage: "Saban might be the greatest college coach ever, and I can honestly say in the last eight years at Alabama I have never once seen him tired. But in Cleveland, under Bill, he'd go slump down against a wall and stutter, "I gotta get out of here, I can't function anymore." Bill could outwork all of us."

Phil Savage: "Saban might be the greatest college coach ever, and I can honestly say in the last eight years at Alabama I have never once seen him tired. But in Cleveland, under Bill, he'd go slump down against a wall and stutter, "I gotta get out of here, I can't function anymore." Bill could outwork all of us."

Rick Venturi: "His philosophy from the beginning was 'No stone left unturned' and 'No envelope unpushed in order to win.' And the result of that was you worked to exhaustion. But he never asked you to do anything he wasn't doing. I look back on that first season as the greatest year in my coaching life."

Rick Venturi: "His philosophy from the beginning was 'No stone left unturned' and 'No envelope unpushed in order to win.' And the result of that was you worked to exhaustion. But he never asked you to do anything he wasn't doing. I look back on that first season as the greatest year in my coaching life."

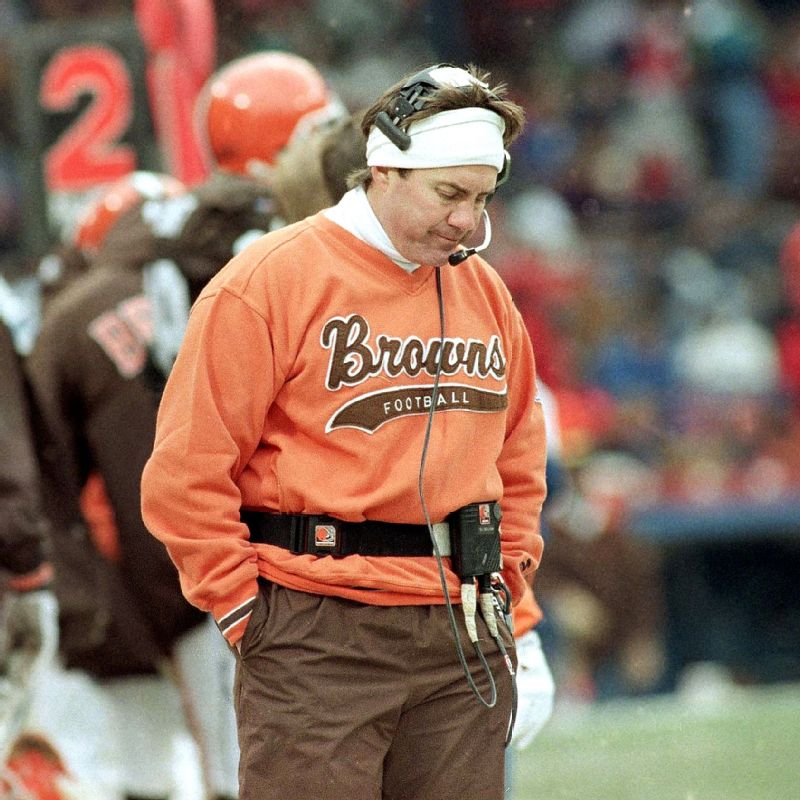

Belichick was the "the fair-haired savior of the Browns" when he took the job in 1991. AP Photo

Devil in the Details

Belichick's love and respect for his father and his contentious relationship with Parcells, both a mentor and a tormentor, left him with a soft spot for younger coaches and staff, aware of how hard he pushed them.

Phil Savage: "He's been in that position himself, living in an empty apartment with a cardboard moving box as your coffee table. So when we'd win a big game, on Monday he'd give you one of those $100 handshakes. It was the kind of gesture people would never, ever connect to Bill Belichick. There's a generosity to Bill most people don't get to see. "

Phil Savage: "He's been in that position himself, living in an empty apartment with a cardboard moving box as your coffee table. So when we'd win a big game, on Monday he'd give you one of those $100 handshakes. It was the kind of gesture people would never, ever connect to Bill Belichick. There's a generosity to Bill most people don't get to see. "

Jon Robinson (Patriots Scout, 2002-09, and Director of College Scouting, 2009-13): "After my daughter was diagnosed at 6 with Type 1 diabetes, a week later on my desk there was a little teddy bear, with a Belichick hoodie on it. And he had written a little note: 'I know this doesn't cure it, but just something for Taylor to know we are thinking about her and praying for her.' She knew it was from Coach. She named her bear Hoodie."

Jon Robinson (Patriots Scout, 2002-09, and Director of College Scouting, 2009-13): "After my daughter was diagnosed at 6 with Type 1 diabetes, a week later on my desk there was a little teddy bear, with a Belichick hoodie on it. And he had written a little note: 'I know this doesn't cure it, but just something for Taylor to know we are thinking about her and praying for her.' She knew it was from Coach. She named her bear Hoodie."

Mike Whalen (Belichick's Friend, Wesleyan Athletic Director and Former Coach): "My first year as coach at Wesleyan I'm trying to turn things around and I'm recruiting a kid out of West Hartford who was leaning toward Princeton. So I emailed Bill and asked him to call the kid. Bill calls him that same night and the kid hangs up on him. 'Hello, this is Bill Belichick from the New England Patriots,' and the kid goes, 'Yeah, right.' Bill keeps going: 'I'd like to talk to you about Wesleyan and the kind of opportunity you'll have there,' and the kid goes, 'Yeah, yeah, sure, Bill' -- click. Bill emails me and says, 'I reached out to him but, um, I don't think I really connected.'"

Mike Whalen (Belichick's Friend, Wesleyan Athletic Director and Former Coach): "My first year as coach at Wesleyan I'm trying to turn things around and I'm recruiting a kid out of West Hartford who was leaning toward Princeton. So I emailed Bill and asked him to call the kid. Bill calls him that same night and the kid hangs up on him. 'Hello, this is Bill Belichick from the New England Patriots,' and the kid goes, 'Yeah, right.' Bill keeps going: 'I'd like to talk to you about Wesleyan and the kind of opportunity you'll have there,' and the kid goes, 'Yeah, yeah, sure, Bill' -- click. Bill emails me and says, 'I reached out to him but, um, I don't think I really connected.'"

John Harbaugh (Ravens Coach, 2008-Present): "Bill called our owner at like 3 in the morning to recommend me for the Ravens job. I was just really grateful and I couldn't believe it. I called Bill up and thanked him right away. He just said, 'Ah, don't worry about it, you should've had the job three days ago.'"

John Harbaugh (Ravens Coach, 2008-Present): "Bill called our owner at like 3 in the morning to recommend me for the Ravens job. I was just really grateful and I couldn't believe it. I called Bill up and thanked him right away. He just said, 'Ah, don't worry about it, you should've had the job three days ago.'"

Bob Quinn (Detroit Lions General Manager, Former Patriots Scout and Director of Pro Scouting, 2000-15): "I accepted the Lions job at 1 or 2 in the afternoon. His assistant said he was in the weight room on the treadmill. I went down there and he turned the treadmill down and he walked really slow and we just sat there and had a conversation for well over an hour about everything. The river just unloaded. I wish I had a tape recorder. I didn't even have a piece of paper with me, so I was just trying to remember everything. People don't know. They don't see that guy on the treadmill. They see the guy in front of the press podium. One of the things Bill said to me was, 'Don't try to be me, try to be yourself.'"

Bob Quinn (Detroit Lions General Manager, Former Patriots Scout and Director of Pro Scouting, 2000-15): "I accepted the Lions job at 1 or 2 in the afternoon. His assistant said he was in the weight room on the treadmill. I went down there and he turned the treadmill down and he walked really slow and we just sat there and had a conversation for well over an hour about everything. The river just unloaded. I wish I had a tape recorder. I didn't even have a piece of paper with me, so I was just trying to remember everything. People don't know. They don't see that guy on the treadmill. They see the guy in front of the press podium. One of the things Bill said to me was, 'Don't try to be me, try to be yourself.'"

Jim Schwartz: "He did a great job of coaching coaches. It wasn't just the players. He coached the coaches."

Jim Schwartz: "He did a great job of coaching coaches. It wasn't just the players. He coached the coaches."

Phil Savage: "My film breakdowns weren't what he wanted, so he says, 'Let's just sit down and go through a few plays together.' We're getting ready for Tampa, he throws the first play up on the screen and starts going, from the inside out, over every single tiny detail. 'See this split of the linemen? That's 2 feet. That's 3 feet. That one's 2 feet between the center and the guard. Write that down. OK, now look at the splits of the wide receivers. The Z is inside the numbers. The X is outside. OK, the quarterback. Look! Right there! He looks to the left, to the right, to the left, then to the middle and then he hikes the ball. You gotta monitor that because it could help our defensive linemen get a jump on the snap.'"

Phil Savage: "My film breakdowns weren't what he wanted, so he says, 'Let's just sit down and go through a few plays together.' We're getting ready for Tampa, he throws the first play up on the screen and starts going, from the inside out, over every single tiny detail. 'See this split of the linemen? That's 2 feet. That's 3 feet. That one's 2 feet between the center and the guard. Write that down. OK, now look at the splits of the wide receivers. The Z is inside the numbers. The X is outside. OK, the quarterback. Look! Right there! He looks to the left, to the right, to the left, then to the middle and then he hikes the ball. You gotta monitor that because it could help our defensive linemen get a jump on the snap.'"

Jim Schwartz: "Probably the biggest thing I learned from Bill is that there isn't anything that is not important. Anything that touches the team is important. That philosophy of 'Don't sweat the small stuff'? Yeah, that was never his philosophy."

Jim Schwartz: "Probably the biggest thing I learned from Bill is that there isn't anything that is not important. Anything that touches the team is important. That philosophy of 'Don't sweat the small stuff'? Yeah, that was never his philosophy."

Phil Savage: "He proceeds to go through all these little intricacies on the game film ... and it's 20 minutes on one play. Twenty minutes! In my immature mind I'm sitting there in the dark doing the math: Three games to break down on each side of the ball, 60 plays in each game, 20 minutes a play means I can get through three plays in an hour. My god, I'll never sleep again. And I didn't."

Phil Savage: "He proceeds to go through all these little intricacies on the game film ... and it's 20 minutes on one play. Twenty minutes! In my immature mind I'm sitting there in the dark doing the math: Three games to break down on each side of the ball, 60 plays in each game, 20 minutes a play means I can get through three plays in an hour. My god, I'll never sleep again. And I didn't."

Matt Ludtke/AP Photo

Mistakes by the Lake

The 1995 Browns were nearing bankruptcy when, on Nov. 6, owner Art Modell rocked the sports world with the news that the team was moving to Baltimore.

Rick Venturi: "After three years of losing football, they were nearing the end of their rope in Cleveland. We turned it around in 1994. We won 11 games and won the wild-card playoffs. We were really on the cusp of something great there in Cleveland."

Rick Venturi: "After three years of losing football, they were nearing the end of their rope in Cleveland. We turned it around in 1994. We won 11 games and won the wild-card playoffs. We were really on the cusp of something great there in Cleveland."

Heath Evans (Patriots Fullback 2005-08, Current NFL Network Analyst): "Everything was ripped out from underneath him. Nobody in the world could have survived that. It was an absolute dumpster fire, what ownership did to him in Cleveland. If you look at the Bill we know now, the same thing he did in New England was going to happen in Cleveland. I have no doubt that 1995 in Cleveland would have been like the 2001 Super Bowl season in New England if Bill had been allowed to continue to grow and groom his staff and his team."

Heath Evans (Patriots Fullback 2005-08, Current NFL Network Analyst): "Everything was ripped out from underneath him. Nobody in the world could have survived that. It was an absolute dumpster fire, what ownership did to him in Cleveland. If you look at the Bill we know now, the same thing he did in New England was going to happen in Cleveland. I have no doubt that 1995 in Cleveland would have been like the 2001 Super Bowl season in New England if Bill had been allowed to continue to grow and groom his staff and his team."

Rick Venturi: "Once they announced the move, 1995 became as bad as anything I've ever been through from a football standpoint -- a total, miserable death slide. It went from the greatest sports city in the world to an 80,000-person wake on Sundays. Bill would never show it, but it took a toll on him."

Rick Venturi: "Once they announced the move, 1995 became as bad as anything I've ever been through from a football standpoint -- a total, miserable death slide. It went from the greatest sports city in the world to an 80,000-person wake on Sundays. Bill would never show it, but it took a toll on him."

Consolidating Power

After the Browns' final 1995 home game, Belichick's postgame interview under the stadium was drowned out for several minutes by fans chanting "Bill must go!" (The Browns had lost six of their last seven.) As he waited at the lectern for the noise to abate, his firing imminent, his face was a contorted mix of defiance and disappointment. In a way, this was his dad's Vanderbilt moment. If ever he was granted another chance, he'd do everything differently.

But first, penance awaited: Four more years as a Parcells underling, first with the 1996 Patriots and then three seasons in New York with the Jets, where Parcells is said to have mocked Belichick as a so-called genius and failed head coach on an open headset during a game. In 1999, when Parcells retired (temporarily) from coaching, he named Belichick his successor in New York. Concerned about instability with ownership and wanting to step out of Parcells' considerable shadow, Belichick scribbled out a resignation letter on a napkin -- he was quitting as "HC of the NYJ," it stated -- and bolted to New England. The Jets got three draft picks as compensation. Parcells says the two former colleagues have never discussed the defection, which gave Belichick the total control he needed: as head coach and GM.

Phil Savage: "That's the big separator for Bill from everyone else: Usually, the GM handles the business and the coach handles the team. Bill's one of the few out there, if not the only one, who can do both."

Phil Savage: "That's the big separator for Bill from everyone else: Usually, the GM handles the business and the coach handles the team. Bill's one of the few out there, if not the only one, who can do both."

Bob Quinn: "The rest of us can't be both the head coach and the GM. There's only one person who walks on this earth that does it at this level."

Bob Quinn: "The rest of us can't be both the head coach and the GM. There's only one person who walks on this earth that does it at this level."

Phil Savage: "To be great on the field, you have to be emotional. To be great upstairs in the front office, you have to be robotic. The way he can separate in his mind the deep, personal relationships he has to have with his players downstairs in the locker room, on the field and in games, versus the business reality of looking at the same exact players from a strictly financial standpoint, as commodities, when he switches hats upstairs in the front office -- that's not just incredibly hard, that's almost impossible."

Phil Savage: "To be great on the field, you have to be emotional. To be great upstairs in the front office, you have to be robotic. The way he can separate in his mind the deep, personal relationships he has to have with his players downstairs in the locker room, on the field and in games, versus the business reality of looking at the same exact players from a strictly financial standpoint, as commodities, when he switches hats upstairs in the front office -- that's not just incredibly hard, that's almost impossible."

Amy Trask (Raiders CEO, 1997-2013): "In 1998 I recommended to Al Davis that we hire Bill as the Raiders head coach. Al decided to go with Jon Gruden, an offensive-minded coach, which surprised no one in the league. But Al liked Bill very much. Bill made it clear he would always tailor his schemes to maximize his players' talents. That's what the best coaches do, the best business people do and the best leaders do: They put their people in the best possible position to succeed. And that's what Bill does. I was always tickled pink years later when Al would say to me, 'Well, you sure can pick a coach, kid.'"

Amy Trask (Raiders CEO, 1997-2013): "In 1998 I recommended to Al Davis that we hire Bill as the Raiders head coach. Al decided to go with Jon Gruden, an offensive-minded coach, which surprised no one in the league. But Al liked Bill very much. Bill made it clear he would always tailor his schemes to maximize his players' talents. That's what the best coaches do, the best business people do and the best leaders do: They put their people in the best possible position to succeed. And that's what Bill does. I was always tickled pink years later when Al would say to me, 'Well, you sure can pick a coach, kid.'"

Dick Miller: "Occasionally, I get letters from former students that are very nice and make me feel wonderful. This is one of them. It reads: 'I honestly never thought that my economics background would be of much help as a football coach, but with the new salary cap, I need a calculator to break down game films. The creativity of contracts and 'beating the cap' will have a lot to do with each team's success in the NFL in the next few years and I'm sure you'd be very good at it. I always carry many fond thoughts of Wesleyan and your guidance with me and I look forward to the (gulp) 20th (it can't be) reunion this summer. Best wishes for the New Year, Bill Belichick.'"

Dick Miller: "Occasionally, I get letters from former students that are very nice and make me feel wonderful. This is one of them. It reads: 'I honestly never thought that my economics background would be of much help as a football coach, but with the new salary cap, I need a calculator to break down game films. The creativity of contracts and 'beating the cap' will have a lot to do with each team's success in the NFL in the next few years and I'm sure you'd be very good at it. I always carry many fond thoughts of Wesleyan and your guidance with me and I look forward to the (gulp) 20th (it can't be) reunion this summer. Best wishes for the New Year, Bill Belichick.'"

Bob Quinn: "I'd get to the office somewhere between 6 and 6:30 every morning and he was always there. In 15 years I could probably count on both hands the number of times I pulled into the parking lot and he wasn't there. When the leader of the organization does that, it's really easy for everyone else to kind of take that mentality too and say, 'If he's doing it, we all should do it.'"

Bob Quinn: "I'd get to the office somewhere between 6 and 6:30 every morning and he was always there. In 15 years I could probably count on both hands the number of times I pulled into the parking lot and he wasn't there. When the leader of the organization does that, it's really easy for everyone else to kind of take that mentality too and say, 'If he's doing it, we all should do it.'"

Rosevelt Colvin (Patriots Linebacker, 2003-08): "He's football 22/7. He gets maybe two hours of sleep, and the rest of his life is football. He's paid the ultimate sacrifice for this game."

Rosevelt Colvin (Patriots Linebacker, 2003-08): "He's football 22/7. He gets maybe two hours of sleep, and the rest of his life is football. He's paid the ultimate sacrifice for this game."

Rich Ohrnberger (Patriots Lineman, 2009-11): "That's not the easiest environment to be in. It was stressful. It separated you sometimes from your immediate family, but you felt an obligation to this organization to really give your all. At any other place there was a focus on football and winning but never quite to the level of New England. And it really was attributed to how Bill ran the show over there."

Rich Ohrnberger (Patriots Lineman, 2009-11): "That's not the easiest environment to be in. It was stressful. It separated you sometimes from your immediate family, but you felt an obligation to this organization to really give your all. At any other place there was a focus on football and winning but never quite to the level of New England. And it really was attributed to how Bill ran the show over there."

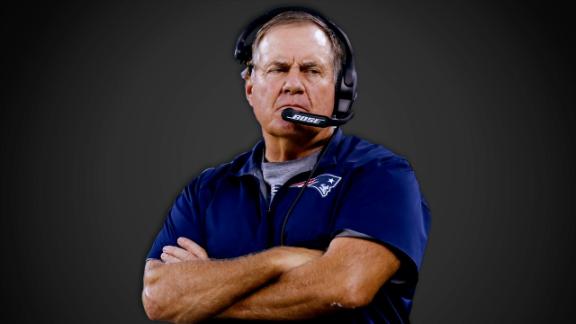

Since a 5-11 season in his first year in Boston, Belichick has never finished a year under .500 again. Matthew J. Lee/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Mike Compton (Patriots Guard, 2001-03): "A bad storm had come through and I overslept. After the team meeting I said, 'Coach, I apologize, the power in Cumberland, Rhode Island, was blacked out because of the storm.' He just looked at me and asked if I knew where a drugstore was and why don't I go buy one of those stopwatches that have an alarm on your wrist and set it. Then he just walked out. I got a letter from the team a few days later saying I had been fined for being late. I bought that alarm watch and have worn it ever since."

Mike Compton (Patriots Guard, 2001-03): "A bad storm had come through and I overslept. After the team meeting I said, 'Coach, I apologize, the power in Cumberland, Rhode Island, was blacked out because of the storm.' He just looked at me and asked if I knew where a drugstore was and why don't I go buy one of those stopwatches that have an alarm on your wrist and set it. Then he just walked out. I got a letter from the team a few days later saying I had been fined for being late. I bought that alarm watch and have worn it ever since."

Curtis Martin: "My rookie year in New England, we'd scrimmage goal-line full go at the end of the practice. Seven or eight times in a row he told the defense I was running and jumping over the top and to keep me from getting in. He would literally tell them what side I was going to run on. They were just teeing off on me. But out of eight times, I got the ball in the end zone like five times. He wanted to see what type of fight I had in me, if I would break."

Curtis Martin: "My rookie year in New England, we'd scrimmage goal-line full go at the end of the practice. Seven or eight times in a row he told the defense I was running and jumping over the top and to keep me from getting in. He would literally tell them what side I was going to run on. They were just teeing off on me. But out of eight times, I got the ball in the end zone like five times. He wanted to see what type of fight I had in me, if I would break."

Kevin Faulk (Patriots Running Back, 1999-2011): "When he first got to New England, for almost three years I'd see Bill in the hallway going to breakfast at the facility. Now, I'm from Louisiana. I don't care who you are, I'm going to say 'Good morning, how you doing? How's everything today?' But for the longest time I'd walk right past Coach Belichick, say 'Good morning!' and I'd get nothing back. Nothing. I said good morning to him for years. Then, one day I said it and he finally looked up and said, 'Good morning, Kevin,' and so I reached out and I stopped him, and he was like, 'Whoa, whoa, Kevin, what are you doing? What's wrong?' And I said, 'You said good morning! Do you know how long I've been saying good morning to you and you haven't said a word?' He just says, 'Aw, Kevin, my bad' and walks away."

Kevin Faulk (Patriots Running Back, 1999-2011): "When he first got to New England, for almost three years I'd see Bill in the hallway going to breakfast at the facility. Now, I'm from Louisiana. I don't care who you are, I'm going to say 'Good morning, how you doing? How's everything today?' But for the longest time I'd walk right past Coach Belichick, say 'Good morning!' and I'd get nothing back. Nothing. I said good morning to him for years. Then, one day I said it and he finally looked up and said, 'Good morning, Kevin,' and so I reached out and I stopped him, and he was like, 'Whoa, whoa, Kevin, what are you doing? What's wrong?' And I said, 'You said good morning! Do you know how long I've been saying good morning to you and you haven't said a word?' He just says, 'Aw, Kevin, my bad' and walks away."

Rick Venturi: "He has a very dry, cynical sense of humor. A couple of times we'd hit the parking lot at the same time in the morning, and on the way into the facility he'd comment on The Howard Stern Show. 'Was that hilarious or what?' he'd say. He's a real closet rock 'n' roll nut. He traveled with the Rolling Stones for a few weeks through Europe one summer. Bon Jovi used to come to Cleveland and catch passes in practice. He had a suite in Cleveland and we all went to Pink Floyd together as a group. I didn't see him with his lighter out, but it wouldn't surprise me if I did."

Rick Venturi: "He has a very dry, cynical sense of humor. A couple of times we'd hit the parking lot at the same time in the morning, and on the way into the facility he'd comment on The Howard Stern Show. 'Was that hilarious or what?' he'd say. He's a real closet rock 'n' roll nut. He traveled with the Rolling Stones for a few weeks through Europe one summer. Bon Jovi used to come to Cleveland and catch passes in practice. He had a suite in Cleveland and we all went to Pink Floyd together as a group. I didn't see him with his lighter out, but it wouldn't surprise me if I did."

Rosevelt Colvin: "Bill knew what was going on with everything at every moment. Unless Bon Jovi was there. Then he couldn't care less what was going on."

Rosevelt Colvin: "Bill knew what was going on with everything at every moment. Unless Bon Jovi was there. Then he couldn't care less what was going on."

Phil Savage: "He really doesn't care what he looks like. The cutoff sweatshirts? The hoodies? Some of our older veteran coaches and scouts would make comments like, 'What's the deal with our head coach, the guy looks like hell?'"

Phil Savage: "He really doesn't care what he looks like. The cutoff sweatshirts? The hoodies? Some of our older veteran coaches and scouts would make comments like, 'What's the deal with our head coach, the guy looks like hell?'"

Bob Quinn: "There's not a lot of small talk with Bill. Not a lot of, 'Hey, what did you do this weekend?' He gets to the point very quickly in conversations. There's no mincing words."

Bob Quinn: "There's not a lot of small talk with Bill. Not a lot of, 'Hey, what did you do this weekend?' He gets to the point very quickly in conversations. There's no mincing words."

Aqib Talib (Patriots Cornerback, 2012-13): "That's how he is with everybody, no games -- OK, a few games, but he's not going to beat around the bush. He's going to tell you if you're playing terrible, if you're playing like s---, if you're playing great. He's not scared to tell you any of that. Clear-cut, direct, straightforward."

Aqib Talib (Patriots Cornerback, 2012-13): "That's how he is with everybody, no games -- OK, a few games, but he's not going to beat around the bush. He's going to tell you if you're playing terrible, if you're playing like s---, if you're playing great. He's not scared to tell you any of that. Clear-cut, direct, straightforward."

Phil Savage: "He's not going to fly off the handle and yell and scream at people. That's just not his personality."

Phil Savage: "He's not going to fly off the handle and yell and scream at people. That's just not his personality."

Rick Venturi: "He has the most unique way of just getting under everyone's skin. In Cleveland, we ran a cover 2 technique -- where the defensive backs had to jam and run -- that was not easy to teach, and my guys were really struggling with it. Bill just turns to me in front of everyone and says, 'This s--- is getting really hard to watch.' And that's it. And you're just going, 'Aw, goddamn it,' and your whole body is tense -- I don't know how to put it in words, but you went home and just said to yourself, 'I will never let this s--- happen again.'"

Rick Venturi: "He has the most unique way of just getting under everyone's skin. In Cleveland, we ran a cover 2 technique -- where the defensive backs had to jam and run -- that was not easy to teach, and my guys were really struggling with it. Bill just turns to me in front of everyone and says, 'This s--- is getting really hard to watch.' And that's it. And you're just going, 'Aw, goddamn it,' and your whole body is tense -- I don't know how to put it in words, but you went home and just said to yourself, 'I will never let this s--- happen again.'"

Akiem Hicks (Patriots Defensive End, 2015): "My first game with Bill, I made a play and gave the crowd a little hype signal. And I got back to the sidelines, and he just chewed me out. He said a bunch of expletives to me. It's ingrained in my mind. Bill doesn't mind if it's a passionate thing you do, you make a big play and get up and be excited, but there's a range where, anything after three seconds, you cut that off. Believe me, after that one I didn't step on any other lines."

Akiem Hicks (Patriots Defensive End, 2015): "My first game with Bill, I made a play and gave the crowd a little hype signal. And I got back to the sidelines, and he just chewed me out. He said a bunch of expletives to me. It's ingrained in my mind. Bill doesn't mind if it's a passionate thing you do, you make a big play and get up and be excited, but there's a range where, anything after three seconds, you cut that off. Believe me, after that one I didn't step on any other lines."

Phil Savage: "He will say something to you in a sarcastic tone that, wow, is just so right to the core. It hits home twice as hard and makes you feel about an inch tall."

Phil Savage: "He will say something to you in a sarcastic tone that, wow, is just so right to the core. It hits home twice as hard and makes you feel about an inch tall."

Kathy Willens/AP Photo

With the 199th Pick ...

Even for a coaching prodigy with a withering sense of humor, Belichick's ultimate success as a head coach is due, in a significant way, to an enormous stroke of luck. During the sixth round of the 2000 draft, instead of taking quarterback Tim Rattay with the 199th pick, the Patriots selected Michigan's Tom Brady. After Brady replaced an injured Drew Bledsoe in '01, the Patriots won three of the next four Super Bowls.

Rick Venturi: " When you get a guy like Brady that late in the draft, that's just lucky. But the Patriots kept four quarterbacks in 2000, which is pretty rare. So maybe the brilliance wasn't in drafting Brady but in Bill's recognition right away that he had something special when no one else knew it."

Rick Venturi: " When you get a guy like Brady that late in the draft, that's just lucky. But the Patriots kept four quarterbacks in 2000, which is pretty rare. So maybe the brilliance wasn't in drafting Brady but in Bill's recognition right away that he had something special when no one else knew it."

Adam Vinatieri (Patriots kicker, 1996-2005): "I think the first Super Bowl season was probably the year that it really switched for Bill. The first couple of years, we were a little shaky while he was getting his personnel lined up. Bledsoe gets banged up, Brady comes in, and we start winning games. When Brady first came in, his first start, the rest of the team was like, "This is a young kid, we have to step up and help each other." Bill didn't see it that way. He told us not to try to do too much by thinking we had to cover up for others. We followed his lead and it worked. That's when they started drinking the Kool-Aid of believing that Bill knew what he was doing and that Bill had a vision."

Adam Vinatieri (Patriots kicker, 1996-2005): "I think the first Super Bowl season was probably the year that it really switched for Bill. The first couple of years, we were a little shaky while he was getting his personnel lined up. Bledsoe gets banged up, Brady comes in, and we start winning games. When Brady first came in, his first start, the rest of the team was like, "This is a young kid, we have to step up and help each other." Bill didn't see it that way. He told us not to try to do too much by thinking we had to cover up for others. We followed his lead and it worked. That's when they started drinking the Kool-Aid of believing that Bill knew what he was doing and that Bill had a vision."

A Madness to his Methods

Thirty-some years after he aced the Lions' coaching quiz to land a job in Detroit, Belichick's own weekly player exams, meticulous game prep and increasingly relentless pursuit of every possible advantage become part of Patriots dynasty lore.

Terrell McClain: (Patriots defensive tackle, 2012): The Patriots are more like a private school. They don't like business getting outside. They like to keep everything inside, even scouting reports. If a piece of paper is on the floor, it gets crumpled up and thrown away. They make sure you turn everything back in and shred all that stuff."

Terrell McClain: (Patriots defensive tackle, 2012): The Patriots are more like a private school. They don't like business getting outside. They like to keep everything inside, even scouting reports. If a piece of paper is on the floor, it gets crumpled up and thrown away. They make sure you turn everything back in and shred all that stuff."

Adam Vinatieri: He knew what was going on in the building at all times. He controlled which doors we went out of. The way in and out of our locker room to our cars was right by his office. I think when they built it, there was probably planning involved."

Adam Vinatieri: He knew what was going on in the building at all times. He controlled which doors we went out of. The way in and out of our locker room to our cars was right by his office. I think when they built it, there was probably planning involved."

Rosevelt Colvin: "At practice, Bill twirls that whistle around his two fingers, watching everything, seeing everything. He could be on another field, I'm not kidding now, he could be on another field and come running over because he saw that the key guy on a kickoff return missed his block."

Rosevelt Colvin: "At practice, Bill twirls that whistle around his two fingers, watching everything, seeing everything. He could be on another field, I'm not kidding now, he could be on another field and come running over because he saw that the key guy on a kickoff return missed his block."

Phil Savage: "Most coaches specialize on one side of the ball. But he's one of the few out there who have a global perspective of the entire game and all 22 positions. He's a true coach of all 22 positions plus every specialist. That's a rarity. He's one of the few coaches out there who, if you dropped him on the staff at Drake University and said, 'Hey, be the tight ends coach,' he could absolutely coach those tight ends to the nth degree."

Phil Savage: "Most coaches specialize on one side of the ball. But he's one of the few out there who have a global perspective of the entire game and all 22 positions. He's a true coach of all 22 positions plus every specialist. That's a rarity. He's one of the few coaches out there who, if you dropped him on the staff at Drake University and said, 'Hey, be the tight ends coach,' he could absolutely coach those tight ends to the nth degree."

Rosevelt Colvin: "The dude's a walking football encyclopedia. He can give you the history of the spread formation or the single wing. I tell people all the time, if you ever had a conversation with him about football it would be one of the greatest conversations you ever had in your whole life."

Rosevelt Colvin: "The dude's a walking football encyclopedia. He can give you the history of the spread formation or the single wing. I tell people all the time, if you ever had a conversation with him about football it would be one of the greatest conversations you ever had in your whole life."

Jon Robinson: "He always migrated toward the defensive line at some point in practice. It was cool to see him work with Vince Wilfork, teaching him technique in his early stages."

Jon Robinson: "He always migrated toward the defensive line at some point in practice. It was cool to see him work with Vince Wilfork, teaching him technique in his early stages."

Vince Wilfork (Patriots Nose Tackle, 2004-14): "I had no idea what I was doing in a 34 defense; I had never played it before. Every day he worked with me. He made me understand it. There were times when I was pissed off. But he's the one I credit for the career I've had. He never took his foot off the pedal."

Vince Wilfork (Patriots Nose Tackle, 2004-14): "I had no idea what I was doing in a 34 defense; I had never played it before. Every day he worked with me. He made me understand it. There were times when I was pissed off. But he's the one I credit for the career I've had. He never took his foot off the pedal."

Aqib Talib: "Once, in practice, Brady threw a seam ball that was intercepted, and Bill, man, he chewed Tom out, saying, 'You got 130 career interceptions,' or whatever it was, 'and half of them are on this route. You keep doing the same s--- over and over and this is what happens.' Right then you know two things about the Patriots and Bill Belichick: Everybody is treated the same, and you better get your s--- together."

Aqib Talib: "Once, in practice, Brady threw a seam ball that was intercepted, and Bill, man, he chewed Tom out, saying, 'You got 130 career interceptions,' or whatever it was, 'and half of them are on this route. You keep doing the same s--- over and over and this is what happens.' Right then you know two things about the Patriots and Bill Belichick: Everybody is treated the same, and you better get your s--- together."

Kevin Faulk: "I loved when Bill would yell at Tom Brady and say, 'Hey, Tom, I could go get the quarterback at Foxborough High to do it better than that.'"

Kevin Faulk: "I loved when Bill would yell at Tom Brady and say, 'Hey, Tom, I could go get the quarterback at Foxborough High to do it better than that.'"

Rosevelt Colvin: "Any time something bad happened at practice, the two words you don't ever want to hear come out of his mouth are 'Take off.' That Bill-ism means just get out of his sight and run a lap around the field. If he was really pissed off, he'd yell 'Take off,' wait a few seconds and then add 'Everybody!' and that meant coaches included, even the old guys and heavy guys. We'd all circle back, inching up, hoping not to hear 'Keeeeep going.'"

Rosevelt Colvin: "Any time something bad happened at practice, the two words you don't ever want to hear come out of his mouth are 'Take off.' That Bill-ism means just get out of his sight and run a lap around the field. If he was really pissed off, he'd yell 'Take off,' wait a few seconds and then add 'Everybody!' and that meant coaches included, even the old guys and heavy guys. We'd all circle back, inching up, hoping not to hear 'Keeeeep going.'"

Kevin Faulk: "We prepared for everything. Not saying we perfected it, but we prepared for everything. There's no second-guessing or hesitation when you play for Bill. When you have to think on the field, it slows you down. When you know exactly what you're doing and how to do it and why you're doing it, that allows you to play faster, and your talent flows freely. It's like being in class. They hand you a test, you open it up, look at the questions and go, 'Wow, I know all the answers already.'"

Kevin Faulk: "We prepared for everything. Not saying we perfected it, but we prepared for everything. There's no second-guessing or hesitation when you play for Bill. When you have to think on the field, it slows you down. When you know exactly what you're doing and how to do it and why you're doing it, that allows you to play faster, and your talent flows freely. It's like being in class. They hand you a test, you open it up, look at the questions and go, 'Wow, I know all the answers already.'"

"I kneel at the altar of Vince Lombardi, Chuck Noll, Tom Landry and Bill Walsh, but he may go down as the best," says Rick Venturi. Wendy Maeda/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Matt Cassel (Patriots Quarterback, 2005-08): "Every Tuesday during the season, the quarterbacks would sit down with him and get his scouting report. He'd go through, in a detailed report, the strengths and weaknesses of every opponent that we were going up against. Mainly DBs, sometimes linebackers. But also we'd talk about the defensive coordinator, his philosophy, where he came from, his background, and he'd give you, basically, a great understanding of who your opponent is going to be."

Matt Cassel (Patriots Quarterback, 2005-08): "Every Tuesday during the season, the quarterbacks would sit down with him and get his scouting report. He'd go through, in a detailed report, the strengths and weaknesses of every opponent that we were going up against. Mainly DBs, sometimes linebackers. But also we'd talk about the defensive coordinator, his philosophy, where he came from, his background, and he'd give you, basically, a great understanding of who your opponent is going to be."

Don Jones (Patriots Safety, 2014): "Tuesday they would give us the scouting report, and on Wednesday morning Bill would go around the whole room -- from Tom Brady down to the bottom man on the roster -- and ask everybody about the person they were going against. You really didn't want to be the one not to know."

Don Jones (Patriots Safety, 2014): "Tuesday they would give us the scouting report, and on Wednesday morning Bill would go around the whole room -- from Tom Brady down to the bottom man on the roster -- and ask everybody about the person they were going against. You really didn't want to be the one not to know."

Heath Evans: "Those Q&A's could get really, really stressful because he could ask you anything and you'd better know it. [Former Patriots tackle] Matt Light always sat right behind me, so any time Bill did ask me a question early on, Matt would be whispering in my ear all the wrong answers."

Heath Evans: "Those Q&A's could get really, really stressful because he could ask you anything and you'd better know it. [Former Patriots tackle] Matt Light always sat right behind me, so any time Bill did ask me a question early on, Matt would be whispering in my ear all the wrong answers."

Darius Butler (Patriots Cornerback, 2009-10): "He's a big reader, things like The Art of War, and he would tie the books into day-to-day life. He would have quotes around the facility. He'd ask you what a sign says above a door and you'd have to know what it said. It was things you wouldn't think related to football, but they actually did."

Darius Butler (Patriots Cornerback, 2009-10): "He's a big reader, things like The Art of War, and he would tie the books into day-to-day life. He would have quotes around the facility. He'd ask you what a sign says above a door and you'd have to know what it said. It was things you wouldn't think related to football, but they actually did."

Adam Vinatieri: "There were times when he would surprise you and ask you a certain teammate's wife's name."

Adam Vinatieri: "There were times when he would surprise you and ask you a certain teammate's wife's name."

Darius Butler: "He wants you to know your teammates and have a certain respect for them. That's something a lot of other places don't harp on. But from that point on, it's something that's important to you because it's important to him."

Darius Butler: "He wants you to know your teammates and have a certain respect for them. That's something a lot of other places don't harp on. But from that point on, it's something that's important to you because it's important to him."

Don Jones: "He'd be like, 'Don Jones, so tell me about that gunner.' I'd say, 'He's No. 46. His name is Alfred Morris. He's very fast off the ball, likes to use the swim move. He likes to break down and tackle you, finish you. He's big but soft on the point of attack.'"

Don Jones: "He'd be like, 'Don Jones, so tell me about that gunner.' I'd say, 'He's No. 46. His name is Alfred Morris. He's very fast off the ball, likes to use the swim move. He likes to break down and tackle you, finish you. He's big but soft on the point of attack.'"

Heath Evans: "You're in a Friday red zone meeting, Bill pulls out a sheet of paper and starts asking, 'Hey, Kevin Faulk, what's the Indianapolis Colts' favorite blitz on third down and short in the red zone in the fourth quarter?' Kevin would give an answer and he'd be like, 'Heath, do you agree?' And I'd be like, 'Yes sir, I agree, but they also like to run this one.' Corey would just make up answers if he didn't study. Bill would ask, 'Hey, Corey Dillon, what do you think about their two answers?' And if Corey would say, 'Yeah, I agree, Coach," he'd be like, 'OK, Corey, if you agree, then tell me what's their favorite blitz on first-and-10 inside the red zone?' He never let anyone get away with maybe knowing or not knowing."

Heath Evans: "You're in a Friday red zone meeting, Bill pulls out a sheet of paper and starts asking, 'Hey, Kevin Faulk, what's the Indianapolis Colts' favorite blitz on third down and short in the red zone in the fourth quarter?' Kevin would give an answer and he'd be like, 'Heath, do you agree?' And I'd be like, 'Yes sir, I agree, but they also like to run this one.' Corey would just make up answers if he didn't study. Bill would ask, 'Hey, Corey Dillon, what do you think about their two answers?' And if Corey would say, 'Yeah, I agree, Coach," he'd be like, 'OK, Corey, if you agree, then tell me what's their favorite blitz on first-and-10 inside the red zone?' He never let anyone get away with maybe knowing or not knowing."

Bob Quinn: "You always had to be on your toes because you never know when you're going to cross paths with Bill. He would just be waiting for the omelet station at 6:45 a.m., and he'd ask a question about pro scouting or something and you'd have a half-hour conversation right there."

Bob Quinn: "You always had to be on your toes because you never know when you're going to cross paths with Bill. He would just be waiting for the omelet station at 6:45 a.m., and he'd ask a question about pro scouting or something and you'd have a half-hour conversation right there."

Matt Cassel: My rookie year, I got crushed in the back by a corner blitz against the Giants. We're playing them the next year in the last preseason game. He asks me, 'OK, Cassel, what front do they like to bring the corner blitz from?' I had looked it up the night before, anticipating it. I said, 'Coach, it's an over.' And he goes, 'Brady?' Well, you know immediately when he goes to the next guy: 'Oh, no. Oh, no.' And Brady says, 'An under.' And he goes, 'Brady's right. I don't want to have to send your mother another note that says, 'Dear Mrs. Cassel, we regret to inform you that your son got killed being a dumbass.'"

Matt Cassel: My rookie year, I got crushed in the back by a corner blitz against the Giants. We're playing them the next year in the last preseason game. He asks me, 'OK, Cassel, what front do they like to bring the corner blitz from?' I had looked it up the night before, anticipating it. I said, 'Coach, it's an over.' And he goes, 'Brady?' Well, you know immediately when he goes to the next guy: 'Oh, no. Oh, no.' And Brady says, 'An under.' And he goes, 'Brady's right. I don't want to have to send your mother another note that says, 'Dear Mrs. Cassel, we regret to inform you that your son got killed being a dumbass.'"

Mike Whalen: "You want to know what kind of influence and control he has over this franchise? Listen to his players. It's totally, exactly the same things Bill says. That resonates with every single coach out there. Same page. Same message. Same culture. When you get to a point when you hear your players talking and answering questions very similarly to the way you would answer, you know the philosophy is in place, they're all in, they drank the Kool-Aid."

Mike Whalen: "You want to know what kind of influence and control he has over this franchise? Listen to his players. It's totally, exactly the same things Bill says. That resonates with every single coach out there. Same page. Same message. Same culture. When you get to a point when you hear your players talking and answering questions very similarly to the way you would answer, you know the philosophy is in place, they're all in, they drank the Kool-Aid."

Rick Venturi: "If he has a motivational style, I'd say that it's constant emotional discomfort. That's why his teams never flatline."

Rick Venturi: "If he has a motivational style, I'd say that it's constant emotional discomfort. That's why his teams never flatline."

Through the Gate

Belichick's turn from good guy to villain, in the eyes of his detractors, started in 2007, when the Patriots were caught illegally videotaping Jets coaches' defensive signals in a Week 1 matchup. The Patriots won the game and then the next 17, heading into Super Bowl XLII undefeated. New England's 17-14 loss to the Giants in that game crushed Belichick -- those who were there say he was left broken and apologizing to his team. That season, for his role in the so-called Spygate, the NFL handed Belichick the largest fine in league history ($500,000) and took away the Patriots' first-round draft pick. As New England continued its roll toward its fourth Super Bowl win, in February 2015, and beyond, other incidents exposed Belichick's trademark gamesmanship as something closer to habitual rule-bending. Does it change his place in history? Does he even care that we're focused on his controversies instead of his coaching genius?

Heath Evans: "I never had greater admiration for a man besides my father than I had for Bill after the Super Bowl XLII loss. To the 53 men in that locker room and the coaching staff, he delivered a heartfelt apology. He felt like he had really let us down. Despite 18-1 being the most bitter pill I think you can swallow in sports, when I walked out of that Super Bowl locker room that night I still left with kind of a shining moment in my mind about Bill Belichick, how a man that everybody swears is so arrogant and so self-centered is really the exact opposite."

Heath Evans: "I never had greater admiration for a man besides my father than I had for Bill after the Super Bowl XLII loss. To the 53 men in that locker room and the coaching staff, he delivered a heartfelt apology. He felt like he had really let us down. Despite 18-1 being the most bitter pill I think you can swallow in sports, when I walked out of that Super Bowl locker room that night I still left with kind of a shining moment in my mind about Bill Belichick, how a man that everybody swears is so arrogant and so self-centered is really the exact opposite."

Mike Whalen: "Bill can take a lesser talent and convince them that if they buy in completely and do their job within his system, they will all get to a level that will far surpass what any of them could ever do on their own. That's why you don't have to be a Tedy Bruschi or a Tom Brady to be a leader there. If you're someone who puts the team first and always does your job, then in his system you will be viewed as a leader. That's how you produce something like what Malcolm Butler did in the Super Bowl. That's Bill's strength and his legacy."

Mike Whalen: "Bill can take a lesser talent and convince them that if they buy in completely and do their job within his system, they will all get to a level that will far surpass what any of them could ever do on their own. That's why you don't have to be a Tedy Bruschi or a Tom Brady to be a leader there. If you're someone who puts the team first and always does your job, then in his system you will be viewed as a leader. That's how you produce something like what Malcolm Butler did in the Super Bowl. That's Bill's strength and his legacy."

Curtis Martin: "There will always be that question with Bill because Spygate and Deflategate happened. I see it as someone so driven to get every single edge. But I also see it as someone who didn't need that. I see it as that tipping point, that over-the-top part of perfectionism to get every single advantage."

Curtis Martin: "There will always be that question with Bill because Spygate and Deflategate happened. I see it as someone so driven to get every single edge. But I also see it as someone who didn't need that. I see it as that tipping point, that over-the-top part of perfectionism to get every single advantage."

Rosevelt Colvin: "He knows all the gray areas and knows most of, if not all, the rules, and he wants to gain an advantage the best way possible. If the rule says you can inflate a ball to 15 psi ... Bill is going to inflate that thing right to exactly 15 psi. I've never heard him say we're going to deliberately break the rules or cheat. He just tried to be on the edge, the cutting edge, of what can and cannot be. It's like this with Bill: Is this the limit? OK, then let's go to the limit."

Rosevelt Colvin: "He knows all the gray areas and knows most of, if not all, the rules, and he wants to gain an advantage the best way possible. If the rule says you can inflate a ball to 15 psi ... Bill is going to inflate that thing right to exactly 15 psi. I've never heard him say we're going to deliberately break the rules or cheat. He just tried to be on the edge, the cutting edge, of what can and cannot be. It's like this with Bill: Is this the limit? OK, then let's go to the limit."

Could the Lombardi Trophy have a new name by the time Belichick retires? David J. Phillip/AP Photo

Former NFL Coach: "He will step across the line at any point he thinks he can get away with it. That [stuff] happens. It absolutely fits with the culture and the mindset there. It's all about winning, and when you're working 23 hours a day looking for every advantage and you have your whole life invested in the outcome of a football game, honestly, how long before you start to think, 'Well, if I go just a little bit further with pushing the envelope, what's the difference?' The harder you work and the more you're invested in it, the more you start to think like Bill and the easier it becomes to justify it."

Curtis Martin: "I don't think most people in the football world would see that as something that undermines his coaching ability. I see it as two separate things. It'll be hard for the controversies not to be mentioned. It may be a tagalong, but I don't think it defines him. It shouldn't take away what he's been able to accomplish."

Curtis Martin: "I don't think most people in the football world would see that as something that undermines his coaching ability. I see it as two separate things. It'll be hard for the controversies not to be mentioned. It may be a tagalong, but I don't think it defines him. It shouldn't take away what he's been able to accomplish."

Kevin Faulk: "It does take away from it. I'm not going to say it doesn't bother him, because we're all human, so, yes, he's going to think about it. He's not going to show it to you because that's just not him, but he cares. We all care. Because now you're talking about our legacy as a team, as an organization."

Kevin Faulk: "It does take away from it. I'm not going to say it doesn't bother him, because we're all human, so, yes, he's going to think about it. He's not going to show it to you because that's just not him, but he cares. We all care. Because now you're talking about our legacy as a team, as an organization."

Amy Trask: "I consider Bill the best coach in NFL history, notwithstanding the other issues that have been raised."

Amy Trask: "I consider Bill the best coach in NFL history, notwithstanding the other issues that have been raised."

John Harbaugh: "He's the best coach in football. I have great respect for him."

John Harbaugh: "He's the best coach in football. I have great respect for him."

Rick Venturi: "I kneel at the altar of Vince Lombardi, Chuck Noll, Tom Landry and Bill Walsh, but he may go down as the best. Noll's Steelers were built in about a year and stayed the same for a decade. But what Bill's done, how he's been so good for so long -- in an era of free agency and the salary cap, where everything is built to make everything equal -- is absolutely amazing. Those of us in this business, even the ones who don't like him, can't help but respect what he's done."

Rick Venturi: "I kneel at the altar of Vince Lombardi, Chuck Noll, Tom Landry and Bill Walsh, but he may go down as the best. Noll's Steelers were built in about a year and stayed the same for a decade. But what Bill's done, how he's been so good for so long -- in an era of free agency and the salary cap, where everything is built to make everything equal -- is absolutely amazing. Those of us in this business, even the ones who don't like him, can't help but respect what he's done."

Rosevelt Colvin: "Take away those Super Bowl losses to the Giants, or add one or two more in the next few years, and the debate about his legacy is easy: You have to start seriously thinking about renaming the Lombardi trophy after this dude."

Rosevelt Colvin: "Take away those Super Bowl losses to the Giants, or add one or two more in the next few years, and the debate about his legacy is easy: You have to start seriously thinking about renaming the Lombardi trophy after this dude."

ESPN reporters Todd Archer, Rich Cimini, Jeff Dickerson, Jeremy Fowler, Greg Garber, Jamison Hensley, Paul Kuharsky, Jeff Legwold, Ivan Maisel, Pat McManamon, Ian O'Connor, Mike Reiss, Michael Rothstein, Phil Sheridan, Mike Triplett and Mike Wells contributed to this report.