The Long-Snapper Diaries

Why a former Green Beret, Texas Longhorn and Seattle Seahawk can't stop searching.

It's quiet in the dim corner of the second-story landing where Nate Boyer lives on a futon.

The landing, covered in dark brown carpet, is a long way from Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, where he long-snapped at the University of Texas, and seems farther still from the Seattle Seahawks' practice facility on the shores of Lake Washington, a spot where Pete Carroll once called Boyer's efforts "extraordinary."

The futon, covered by a white sheet with gray stripes, is a humble home for a Bronze Star recipient who in 2008 climbed to the roof of a building in Iraq, where he and a fellow Green Beret battled insurgents.

His possessions -- boxes full of jeans, books, blankets and a bag containing cleats and a football -- sit on the bed. The only light comes from a nearby bedroom, occupied by one of his roommates, and from windows in the living room downstairs. The only sound comes from a nearby television. The only fresh air comes from a doorway to the roof.

The apartment is a few blocks west of Mid-Wilshire in Los Angeles, a nondescript part of the city that is not the beach, the hills or the hood. Boyer has been in town since shortly after he was cut by the Seahawks in August. He's waiting for the phone to ring, hoping against hope that an NFL team will call, offering another tryout. "I want to be part of changing a culture," he says. "Just like [in] the military -- I wanted to go to the most austere environment, the most dangerous and chaotic."

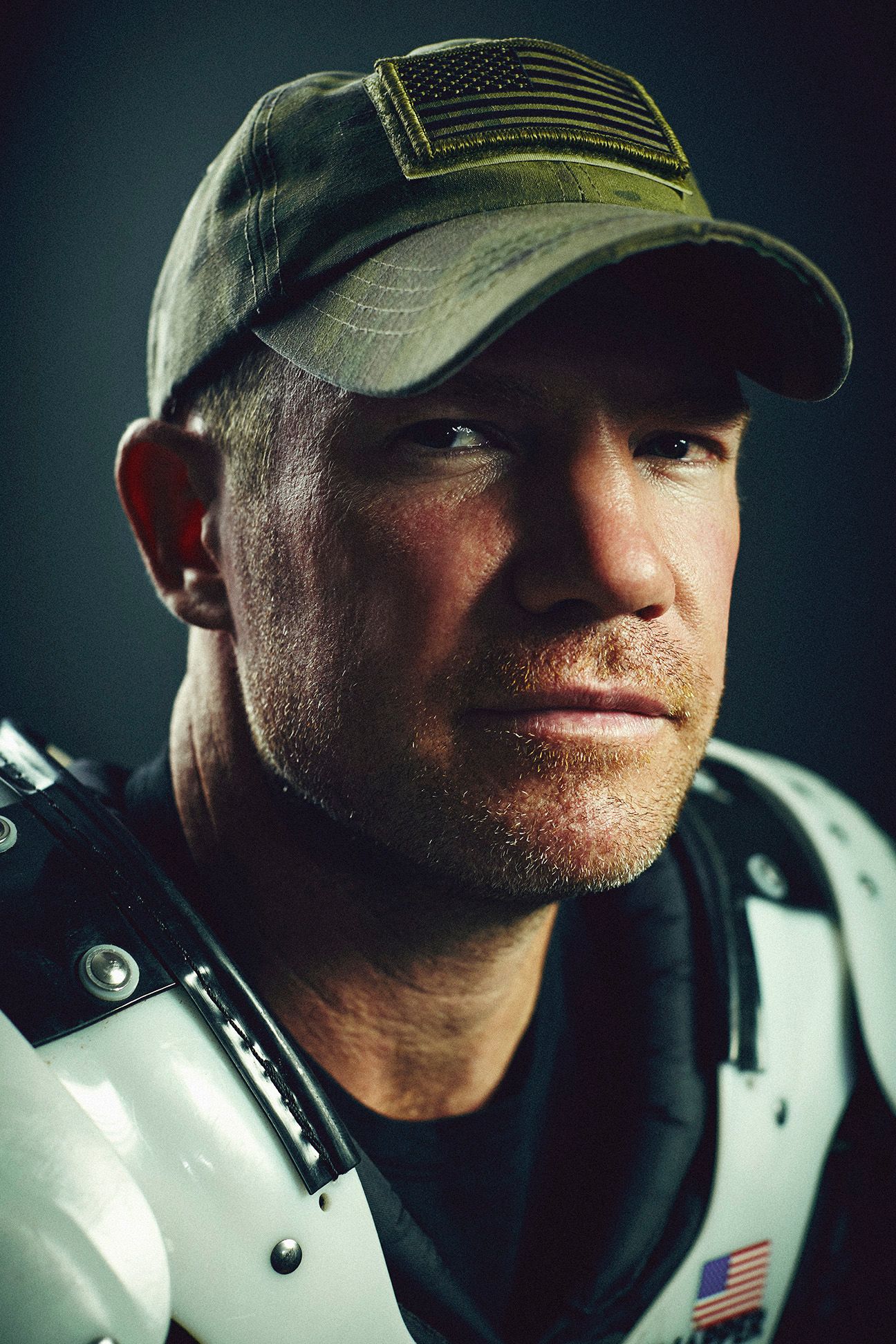

He is disciplined about workouts and remains in fighting shape. Muscles bulge under his gray shirt. His red hair is cropped short. His jaw is steady. But Boyer is 35 years old, and short for a professional football player at just 5-foot-11. Taking stock, he grimaces, shakes his head, twists his neck, looks down at the dark, low-pile carpet and cracks his knuckles.

It won't be enough to sit and wait. Boyer is one of those curiously American characters allergic to the comforts of conventional living, on a constant quest to prove himself. He needs to "fill a void," to search for meaning, to change the world. He has, by turns, been a Che Guevara-inspired globetrotter, a relief aid worker in Darfur, a mentor to autistic children, a soldier in the Special Forces, a long-snapper at a big-time collegiate program, a scrappy free agent trying to be the oldest rookie in the NFL and, most recently, a mountain climber on Mount Kilimanjaro raising awareness about the global clean-water crisis. He has no wife, no children, no dog. He longs for the next adventure. He is ready to go.

As the sun passes overhead, Boyer climbs through the door that opens onto the apartment roof. The view reminds him of Iraq, of the way he moved there. "The low buildings, beige, white. We'd be on those roofs, jumping from building to building ..." he says.

Former Green Beret Nate Boyer's dream came true when the Seahawks signed him in 2015. Despite being released before the regular season, he refuses to give up on his dream.Elaine Thompson/AP Photos

IT'S NIGHT IN the city of Najaf, south of Baghdad, in the fall of 2008.

Staff Sgts. Nate Boyer and Bradley Keys run to a house in the middle of town. They are members of the U.S. 10th Special Forces Group out of Fort Carson, Colorado, on a mission to drive out the enemy. With a 6-foot strip of C-4, they blow down the front door of a home suspected of housing insurgents. At first, the only person they encounter is a frightened boy, about 8 years old, standing in a first-floor hallway, mouth agape. Boyer, 27 years old and 165 pounds, and Keys, a broad-shouldered 29-year-old, brush past the child and race upstairs. With his rifle strapped over his right shoulder, Boyer scrambles onto a balustrade to climb onto the roof, where he suspects insurgents are camping out. Suddenly, bullets fly around him. "I couldn't see anything. There were shots being fired," he would later say. "I was standing on the railing of [the] balcony ... leaning over the top of [the] rooftop, peeking my head over my pistol." If he lets go, he'll fall. He raises his head over the edge. "I see, like, muzzle flashes, and I'm not sure if they're shooting at me." In the dim light, he spots two insurgents. One is running across the rooftop toward him. Does he have a gun? Boyer reaches for his pistol and fires an awkward shot while holding onto the balustrade. He misses. The man turns and jumps off the building. He lands hard, three stories down, and doesn't move.

In the chaos, Boyer sees Keys, already on the roof, racing headlong for the second man. Is he wearing a suicide vest? Keys jumps and tackles him. There is no explosion.

"Brad got the guy," he says.

Brad always got the guy.

Nate Boyer will never forget that night. Over time, it will come to symbolize his years at war: chaos and uncertainty and courage.

At the end of his tour in 2009, Boyer goes to Keys for advice. He can't go home to something quiet. He needs another mission, he thinks, and he has a wild idea. He's taken some general-education courses and is thinking of trying to walk on to a football team at a big school back in the States.

He loves the idea of being a long shot. As a teenager, he hung posters of Jerry Rice and Ronnie Lott on his bedroom walls. At Halloween, he dressed as Joe Montana. Twice. But he's never played a single down for a team at any level, not even pee wee.

"What if I don't make it?" he asks.

"You'll make it, man," Keys says.

Even long after Bradley Keys is killed on a parachute-training jump in Arizona on Dec. 13, 2012, Boyer hears him say, "Trust me. You'll make it."

PEOPLE DRAWN TO Nate Boyer's story tend to think 9/11 inspired him to be a soldier, but the truth is more complicated.

The roots of it lie in a manicured suburb in California's Bay Area, 25 miles southeast of Oakland, a town with quiet winding streets, earth-toned homes and a cozy sense of well-being. A place called Pleasanton.

Boyer moves there with his parents when he is 14. He plays baseball and basketball at Valley Christian High School, and dreams of getting the hell out. There is no single moment that makes him want to go. It's a feeling that grows in him over time -- a contempt. The place is too cut off. Too protected and safe. "All these people so concerned with what job they're going to have that's going to make money -- it was like I was in a bubble," he says.

At 18, he flees to San Diego. "Wouldn't even take our help," says his mother, Laura, an environmental scientist. "He was determined to find his own path." He gets a cramped apartment, enrolls at Mesa Community College and talks himself into a job on a boat that takes people fishing for dorado and yellowtail. He spends part of his first day on deck throwing up.

Before long, he moves to Los Angeles. He runs out of money, and for almost six months lives in a worn Honda Civic hatchback on city streets. Sometimes he sleeps in Griffith Park, or on a patch of grass across from the Beverly Hills Hotel. He showers at the Hollywood YMCA and sometimes scavenges leftovers from restaurants on the Sunset Strip.

“He was determined to find his own path.”

- Boyer's mother, Laura

He falls in with a group of fellow twentysomethings trying to make their way. One is a house painter, another a construction worker and another a tennis pro. Boyer couch-surfs and lives on ramen. His friends call him "Noodles."

Paul Meils, a friend from those days, remembers Noodles rolling his own cigarettes, putting on an English accent to impress women and showing up at bars with his beard half shaved off.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Boyer sees the Twin Towers fall on a 10-inch TV with rabbit ears in a studio apartment near Hollywood. He is 20 years old. The world is bigger and more dangerous than he'd thought, and he is angry but no soldier in waiting. "The military?" Meils says. "Noodles, a Green Beret?"

Deep down he is a loner. And his frustration is growing. His search for meaning is playing out as a series of odd jobs. He works as a sandwich maker at a deli, is a paid mentor to autistic boys in the Hills and gets a nonspeaking role in a Greyhound bus commercial. He's drifting, untethered, becoming the sort of cliché he despises. One afternoon, he drives down a San Fernando Valley freeway and cries. He pleads with God to help him find direction. "I'm 23 by then, and I still have no freakin' clue. I was partying way too much. You end up at these places with these people you can't stand. You're at some house in the Hollywood Hills with a trust-fund baby, and it's just gross, the s--- they are talking about. In my mind, I'm just, 'I want to get the f--- out of here.'"

Along with Fox analyst Jay Glazer, Boyer started MVP, or Merging Veterans and Players, a program that helps soldiers readjust to civilian life. Zachary Bako for ESPN

HE READS "The Motorcycle Diaries," about Guevara's journey as a medical student across South America and his visits to leper colonies and poor villages. He comes to think of Che as a kind of spirit guide. "He was seeking, too, just like I was," Boyer says. He begins to use Che's mantra: Let the world change you and you can change the world. He reads a Time article about genocide in Darfur and is startled by the misery there.

"That's where I'm going," he tells himself. "I'm going to go there and help these people somehow. I'm going to figure out a way to get to these refugee camps and help the people in these pictures."

A half-dozen relief organizations turn him down. He empties his bank account and buys a plane ticket to N'Djamena, the capital of Chad. On Nov. 4, 2004, he arrives wearing a tattered seersucker jacket and flimsy shoes and carrying $200, some Power Bars, a copy of "The Motorcycle Diaries," John Steinbeck's "East of Eden" and Ernest Hemingway's "The Snows of Kilimanjaro."

It takes a few days for him to persuade an aid group in N'Djamena to accept his offer to help and then to get a seat on a United Nations prop plane to a refugee camp near the Sudanese border. Along a road to the camp, he writes in his journal: "We passed donkeys and horses and camels, half of them dead, decaying carcasses, and herds of goats ... No electricity, no school. Straw[-]thatched roofs over mud-bricked walls ... over 100 children. [I] have no way to speak to anyone. [Yet] as night fell, I felt lucky in this place."

He arrives in the city of Abeche, Chad, and begins working in a refugee camp nearby. He feels needed, purposeful. He delivers food and medicine. He plays with kids and teaches them what he can. He tries to comfort the sons and daughters of war -- sick, malnourished, some maimed, many orphaned. Their fathers have been killed and their mothers raped. Children have been marched across the desert. One of the boys, a hobbled 5-year-old named Mustafa, tags along with him. There is something about Mustafa's determination, the way he plays soccer with bigger kids, limping gamely across the dirt, always smiling.

"Mustafa arrived later today, found a ball and headed straight for me," Boyer writes. "We played catch, and then he tried to fool me with the hidden ball trick. I laughed uncontrollably, thought I have never seen anything cuter. He had the older boys from the camp looking up to him, then jealous for his wit and courage."

When he leaves the camp six weeks later, he thinks of Mustafa and the other children. "What are the chances of all of them making it past the brutality they have seen all their lives?" he writes.

Back in N'Djamena, Boyer contracts malaria and is nursed to health by a Chadian family in their home. As he lies on a cot, he listens to radio dispatches from the war in Iraq. "I don't want to be a soldier," he writes. After he recovers, he meets some young Chadians and they talk about the war. We would proudly join the U.S. Army and fight if we could become Americans, the young men tell him. Boyer would later say: "They recognized that [the U.S.] is the country that is asked to come help, the first to go."

In Africa, he finds himself more aware than ever of the advantages that come with being born white and male and middle class in America. He can leave whenever he wants. He can make choices. He decides he wants to do something. Something next. Something big. "I listened to those guys, and that just got me thinking -- maybe the military would be where I would find what I was looking for."

He flies home to Los Angeles. He reads about the Special Forces and how they fight alongside native people against the Taliban or al-Qaida, the kind of militias that made life hell in Africa. He decides to try out for the Green Berets at Fort Benning in Columbus, Georgia. He'll pay a price. He'll redeem his privilege and luck. He'll continue his quest. It's the version of himself he likes best.

Zachary Bako for ESPN

The landing that Boyer calls his bedroom is a long way from Darrell K Royal-Texas Memorial Stadium, where he long-snapped at the University of Texas. Zachary Bako for ESPN (2)

AT FORT BENNING, he can't manage 30 pushups. It takes him 15 minutes to run 2 miles. He fears the Army will send him home. But he thinks of Mustafa and it motivates him to face, even embrace, discomfort in ways he's never thought possible. He works out feverishly, lifting weights, running sprints, wearing a weighted vest and spending his off time doing lunges around a quarter-mile track, lap after lap. Fourteen weeks later, he rifles off 145 pushups and runs 2 miles in 11 minutes.

Next comes Airborne training. If he stumbles, he'll be sent to the regular infantry. But he doesn't. Then comes specialized training. Finally, a grueling, 18-month Special Forces Qualification Course. He hikes alone for 25 miles through mountains and forests in North Carolina. He learns counterterrorism and becomes an expert marksman and a deadly hand-to-hand fighter. He jumps from high-altitude aircraft at night. He learns to evade capture, to survive torture and to live on starvation rations. He stays awake until he hallucinates and makes combat decisions while seeing double. He learns to accept killing and dying for his country. "The hardest hurdle," he says.

Thirty-four soldiers from a class that started out 87 strong receive their Green Beret.

One of them is Noodles.

ON A SUMMER NIGHT in 2008, Nate Boyer steps from the tail of a transport plane at the Baghdad airport. He can see the glare as mortars and rockets streak across the sky. Everything feels close and dangerous.

Days later, he stands watch on a two-lane highway on the outskirts of Najaf. A roadside bomb has blown up a Humvee and Boyer's unit is among the first to arrive and assist. The air is acrid, smoky. Ashes and charred body parts lie on the ground. He looks at the smoldering remains of a soldier he'd spoken with just a few days before. "It hit me then," he would later say. "OK, this is war. This isn't just training or a dream anymore. As much as I would like it to be, this is not just a humanitarian mission. There were people out there; they were trying to kill us, and in some instances we were going to have to kill them."

Eliminating the enemy is the harsh necessity of war, but Boyer ends up learning that a résumé stocked with body counts and pulverized buildings doesn't help the cause in fragile, fractious Iraq. "I came to realize we weren't going to change Iraq with only force -- constantly playing whack-a-mole. This was going to take at least a generation. It wasn't going to be fixed in just a few years. It was going to take time. Commitment, commitment and time."

His last tour ends in 2009, and a letter dated May 18 of that year, from the secretary of the Army, cites Staff Sgt. Boyer's "meritorious combat operations" in keeping with "the finest traditions of military service" and awards him the Bronze Star.

Boyer taught himself to long-snap for field goals and extra points on a soccer field in Athens. Zachary Bako for ESPN

TEXAS COACH Mack Brown doesn't say much at first about the antediluvian walk-on suiting up for spring drills in 2010. Boyer doesn't want the extra attention, and Brown worries about his team's security should it become known that a Green Beret from Iraq is playing for UT.

Some nights, Boyer wakes with a jolt in the middle of the night, dreaming of a firefight. After a workout, a few of the starters, clueless about his past, call out: "Hey, old man, where'd you get those ankle braces? You get crossed over at the YMCA?"

"Nah," Boyer replies. "It was on a night free-fall parachute jump in the Middle East, from about 30,000 feet."

He's exaggerating a little -- it was closer to 20,000 feet -- but he shuts them up.

He wants to be a defensive back, but the Longhorns are coming off the 2010 national title game and he's still learning how to tackle. He takes a redshirt year, dresses for home games and leads Texas onto the field carrying an American flag. The Texas National Guard arranges summer deployments for him. After a summer spent on a non-combat mission to Bulgaria with the 19th Special Forces Group, he plays in a single game in the 2011 season, covering a kickoff against Texas Tech. In the spring of 2012, he goes to Brown's office.

"What can I do? What position could I play where I could get out there on the field?" he asks.

"You're not good enough, Nate," Brown says.

A few days later, Boyer goes back. "Coach, you're losing your snapper," he says. The next summer he'll be deployed with the Green Berets in Greece, and when he isn't on patrol he'll teach himself to long-snap.

"When I get back, I'm going to be your snapper," he says.

"Nate, you are 5-11, 185 pounds. You've got short arms, and you have never snapped a day in your life," Brown says.

On a soccer field in Athens, near the Acropolis, Boyer teaches himself to snap for field goals and extra points. He watches YouTube videos to learn technique. Each ball has to spin at least 7 yards with the accuracy of a dart heading toward a bull's-eye. He imagines himself in games, snapping under the sweating sun. He pictures 300-pound defensive linemen crouching a few feet away, waiting to send him flying. To ease his mind, he reminds himself he has been through worse.

“I can't die now. I've got to get back and play ball next week.”

- Nate Boyer, in Afghanistan in 2014

There is something elementally pleasing about the action, about the connection between body and mind when he snaps a ball. His hands feel purposeful. The tight flight of the ball seems to satisfy him on a deep register. Afternoons alone on the dirt field are full of certainty. This is where the ball must go. This is how you spin it. This is the time it takes to get there.

When he returns to Austin in August 2012, his snaps are fast and accurate. "The biggest surprise I've seen in my coaching life," says former Texas assistant head coach Duane Akina. The Green Beret earns a scholarship and suggests a team slogan: "For the Men on my Left and Right." Players and staff embrace it. "He absolutely became one of our leaders," Brown says.

In the locker room after a win over Baylor that fall, Boyer meets Adm. William McRaven, head of the U.S. Special Operations Command in charge of the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, and soon to become chancellor of the UT system. Boyer tells him he wants to go back to war again, this time in Afghanistan. Maybe he could relieve a Green Beret with a wife and children, he says. He wrestles with competing impulses. Football is an escape from the grim realities of war, and as a player he's something freer, more innocent, than he can be as a soldier. But he's playing out a fantasy on the field, and he knows it. Real work, real stakes, maybe even the real Nate Boyer is out there somewhere in Afghanistan. McRaven sends him to Kabul. "What kind of nutbag wants to spend his summer vacation in college in Afghanistan?" his commanding officer, Colonel Fred Dummar says. "Sounds like my kind of guy." In the summer of 2013, Boyer goes on reconnaissance missions in the Afghan countryside and works for a heavily armed security detail guarding foreign dignitaries.

On the early morning of June 10, sleeping in barracks adjacent to the capital city's main airport, he is jolted awake by the sound of an explosion and bullets slicing against the tin rooftop. He runs to a lookout, "fearful that Taliban were going to blow up our gate and come inside." Instead he sees that a group of enemy fighters have holed up inside a partially constructed building about 220 yards away. They're spraying the area with bullets and launching IEDs, but they're focused mostly on the nearby airport. All morning Boyer will stand watch over his barracks as a battle unfolds between Taliban fighters and Afghan security forces.

"My summer internship," he says.

As the summer wears on, at a camp located on the outskirts of Kabul, Boyer begins practicing for punts. On a dirt field, he builds a plywood target and cuts two holes in it -- one near the ground, for field goals and extra points, and the other for punts. Whenever he can, he snaps. Local Afghans come to watch the American soldier squatting over a dusty ball. He sends it flying again and again, finishing each time by popping up straight with his hands out, ready to block some imaginary lineman.

When he returns to Texas, in addition to extra point and field goal duties, Brown makes him the long-snapper on punts. He is at the center of the line against Ole Miss, Oklahoma State and Texas Tech. He is, as former Longhorns sports information director Bill Little puts it, "a man given the utmost admiration in these parts ...

"If you said in that time frame, name the five most popular Texas football players, Nate would be one of them."

Zachary Bako for ESPN

IN JULY 2014, after his junior year in Austin, his convoy rolls through a peaceful, lush valley in the Tagab district of Afghanistan, northeast of Kabul. The trucks, manned by Green Berets and Afghan troops, finally reach a village -- a maze of low-slung buildings behind high walls. The plan is to park, dismount and search the town, structure by structure, hunting for Taliban.

Without warning, gunfire strafes the column.

The unit pushes close to a wall for cover, but Boyer remains exposed.

He fires back with an M240 Bravo machine gun.

Mohammad Sohrab, his interpreter, now in the United States seeking citizenship, says, "The look on Nate's face was something I won't ever forget. He was so focused. Nothing was going to stop him."

Boyer hears a bullet whistle past his ear. It hits a metal plate about a foot from his temple.

"They're shooting right at me," he thinks.

A few feet away, an Afghan captain is killed. His body lies crumpled in the dirt, a gaping wound in his neck.

The battle rages most of the afternoon.

Boyer fires nearly 1,000 rounds.

"I can't die now," he tells himself. "I've got to get back and play ball next week."

It's strange how the game takes hold of him, how it goes from being a pastime to something essential. Football becomes Nate Boyer's reason to stay alive. It sounds frivolous, but the line between living and dying is frivolous, desperate and small out there. He flies to Darfur to do something great, but at some point he's just trying to make sure the kid who brings him a soccer ball has a reason to smile for a minute in the middle of all that dread. He trains to be a Green Beret to make a difference in the war, but at some point he's in a frenzied firefight and all he can think is, "I can't die now. I've got to get back and play ball next week."

HE MAKES IT BACK to Texas. He is lucky. He plays his senior season, closing it out with a 31-7 loss to Arkansas in the Texas Bowl. When he does the math, he figures he's snapped the football more than 300 times and says he hit the target each time.

"Nate Boyer just has a knack," Brown says.

Brown looks into his chances to play in the NFL and hears nothing but doubt. Too old. Too small. But there's a part of Boyer that relishes shutting up the naysayers. And there's a part of Noodles and Che and Brad living in him every day now that thinks: Why can't the journey from the couch to auditions to refugee camps, from Kabul to Austin, travel next to somewhere equally far-flung and improbable?

Why not pro football?

IN JANUARY 2015, he steps onto athletic trainer and Fox analyst Jay Glazer's doorstep at the Unbreakable Performance Center in Hollywood.

"I heard you can turn me into an NFL player," he says.

"The guy has gray in his hair, so I'm pretty leery," Glazer recalls. "But then I begin hearing all that he had done for the country -- just a little at first; he won't divulge very easily -- and when I realize who I'm talking to, well, to me the guy is Captain America."

He takes Boyer in, offering him a small guest room at his Hollywood house and giving him access to the gym. He talks to his NFL contacts about Boyer. He has some of his friends from the league work out with him. In May, Pete Carroll and the Seahawks sign him as a free agent.

"They're big, fast and strong," Boyer says. "I feel small." He sits in a leather seat at a steak house in Bellevue, Washington, not far from the Seahawks' training camp, and orders a thick-cut filet. "To gain weight," he says. His muscles are quick, anxious. He twists his neck until it pops. He can't sit still.

"What you get with Nate is a sense of physical capability and certainty," Col. Dummar says. "Not that cocky kind of feel -- confidence but also humble. His attitude is just get it done." Clint Gresham, 4 inches taller and the Seahawks' long-snapper since 2010, is the competition. Boyer leans on the words of Brad Keys. He remembers hot afternoons at the Acropolis. "They're not working any harder than me," he says. "If we all put 60-pound packs on our back and went out in the woods, I would smoke every single one of them."

On Aug. 14, 2015, before the kickoff of the Seahawks' first preseason game against Denver, he stands at attention on Century Link Field in Seattle, listening to "The Star-Spangled Banner." Carroll pumps a fist. Earl Thomas slaps him on the back. In the swirling rain, in front of a sold-out stadium, tears stream down his face.

Early in the second half, quarterback Tarvaris Jackson suffers a high-ankle sprain on a third down. Carroll decides to punt. Boyer and punter Jon Ryan jog onto the field.

It's still raining. The crowd is loud, but he doesn't hear it. He listens to sounds on the field. Shouting. Cursing. A teammate slaps him on the butt and says, "Don't screw it up." He gets the signal and flings the ball between his legs. Fifteen yards, straight into Ryan's hands.

Running down the field ... good God, he feels fast. Sheer joy and adrenaline drive him toward the Broncos' end zone. Denver's Jordan Norwood reaches for the ball but bobbles and drops it. Tristan Wade, a Seahawks teammate, lands on the ball. Boyer runs to the spot and leaps, a human exclamation point in his blue No. 48 jersey.

He gets five more snaps, each a bull's-eye. Denver wins 22-20, but Boyer feels good. He's proved he belongs. In the Seahawks' locker room, he showers and puts on jeans and a black T-shirt emblazoned with an American flag and machine guns. Carroll goes over, smiling. "His first play, and the guy is in on a fumble!" he says. "He did just great. He has done everything right. Tonight, it was extraordinary."

A few days later, Boyer walks into the Seahawks' training facility. General manager John Schneider greets him.

"I went up to him and said, 'What's going on?'

"And he was like, 'Uh, man ... we have to let you go.'"

Schneider takes him to Carroll's office. Jackson's injury means the Seahawks have to bring in another quarterback. They can't afford to carry two snappers.

"My thought from the beginning, being an optimist, was 'What if this guy pulls it off and makes the club?'" Carroll says. "This guy, who's to put limits on him?"

Despite his speaking engagements, acting lessons and many other projects, Boyer still hasn't given up on his dream to someday play in the NFL. Zachary Bako for ESPN

TERRORIST ATTACKS in Paris and in San Bernardino, California, make Boyer think about rejoining the Green Berets, but instead he climbs Mount Kilimanjaro, raising money for a charity supporting clean-water wells in Tanzania. After the climb, his thoughts turn more and more to the suffering and injustices he's seen in Darfur, Iraq and Afghanistan.

He talks about the disadvantaged on the radio and in speeches to corporate executives. He speaks to military groups and to veterans in homeless shelters. He and Glazer start a nonprofit called MVP (Merging Veterans and Players) to help former soldiers and ex-NFL players who struggle after their careers end. He interviews members of the military for Peter Berg's production company, Film 44. Maybe if football doesn't work out, he can be a movie producer and give his income to good causes? Or maybe he can act? He takes classes at the Lee Strasberg Theatre & Film Institute in Hollywood. The institute's director, David Lee Strasberg, says Boyer has so much presence that, with a little work, he could star one day on a TV series or in the movies. "To be an actor, you have to be a monster," he says. "Nate is still searching for his monster."

BUT NATE BOYER wants another tryout. Beginning in February, he crashes at the apartment of two old friends from UT -- $800 a month to sleep on the upstairs landing and wait for the phone to ring. He says his agent has heard from at least one team expressing interest, but it isn't Seattle, and it hasn't materialized.

He's lost weight after Kilimanjaro, and he hasn't grown any taller. He works out. The training makes the veins on his arms stand out. The top of his back is rounded with muscle.

But no call.

"I can't quit," he says, sitting on the futon. "I hear from a veteran who is inspired by what I've done, and it's like, 'F---, I just can't let this go.'"

He has rental houses near Fort Bragg, Colorado, and in Colorado Springs, and he's invested the rest of his savings in a bar called HandleBar near the UT campus. But living on the landing is a "way of keeping my hopes up," he says. "I don't need a nice place. I'm content with a piece of ground, just like [in] Darfur."

By now, he has learned some things about himself. Part of his quest is for adrenaline. Part of it is a hunt for moments of Zen. Part of it is wanting simply to matter in this life.

All of it has come at a cost. He has scars outside and in. His neck is stiff and slow to turn. Pain flares in his back and right ankle. He has tinnitus in both ears. In early May, doctors at the Santa Monica (California) VA hospital diagnose him with post-traumatic stress disorder. "It's mostly about some of the sleeping problems and dreams I've had," he says.

Some of his military equipment is stored in a locker, along with a dining-room table and a chest of drawers. Aside from the clothing, books, football and cleats, he doesn't have much. He dates occasionally, but what woman puts up for very long with a life like his? He once thought he would have a family, but now he's not sure that will ever happen. "There is a sort of emptiness," he says.

He isn't Noodles anymore, searching for purpose. But he isn't quite the indomitable Nate Boyer capable of any challenge he dreams up, either. He reflects on what is happening now -- ISIS, the Taliban, Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan in tatters as the U.S. military presence has faded -- and it tears at him. Was the sacrifice worth it? "I don't think a lot of guys died for nothing, but why did we leave? That is what it feels like. Everything we were working for, they took it all away."

Personal doubts sit heavy with him, too. He thinks about the Iraqi his bullet missed, who jumped to his death from the rooftop in Najaf that night. "He ended up not making it," Boyer says, "but what if I had shot that guy and he wasn't armed?" He won't discuss details much, but he knows he has killed other men and he counts the cost of what he's done on the field of battle. The urge to strike out, the quest to do something meaningful, the commitment to a mission changes a person.

It gets harder and harder to be Captain America. There will come a moment when it won't be possible to just keep doing and being more. The signs are there, in that neck pain, in that quiet phone. But he doesn't concede. Not yet.

"I'm motivated by a fear of regret," he says. "The fear of missing out, not exploring -- of one day looking back and seeing that life has passed me by. The fear of not following my heart. I know myself at this point, and it looks like I am always going to be seeking. I'm always going to be feeling empty if I am not pushing myself to do more, to try something new -- to go to the limit."

The drive inside him -- some mix of suburban angst, wanderlust, a jones for the next thrill and a hope to help those in need -- pushes him to take big swings. And then to take them again. He carries a flag onto a football field, wears a flag on his uniform sleeve and plants a flag on the top of a mountain because he is a true believer.

What to do with that feeling now? On the futon. On the landing.

What's next?

"It is going to take my whole lifetime to solve these Third World problems ... but, at the end of the day, that is my goal, save the world," he says. "We are all dying, man. We are all gonna die ... Every day we are one step closer to the end. So go for it. So what, if you don't make it?"