The Waiting Games

The finish line is sometimes only the start of the modern Olympic odyssey, where performance-enhancing drug cases can keep medals in flux for years.

Like a hologram shimmering somewhere in the indefinite future, a virtual podium will hover alongside many upcoming Rio 2016 medal ceremonies.

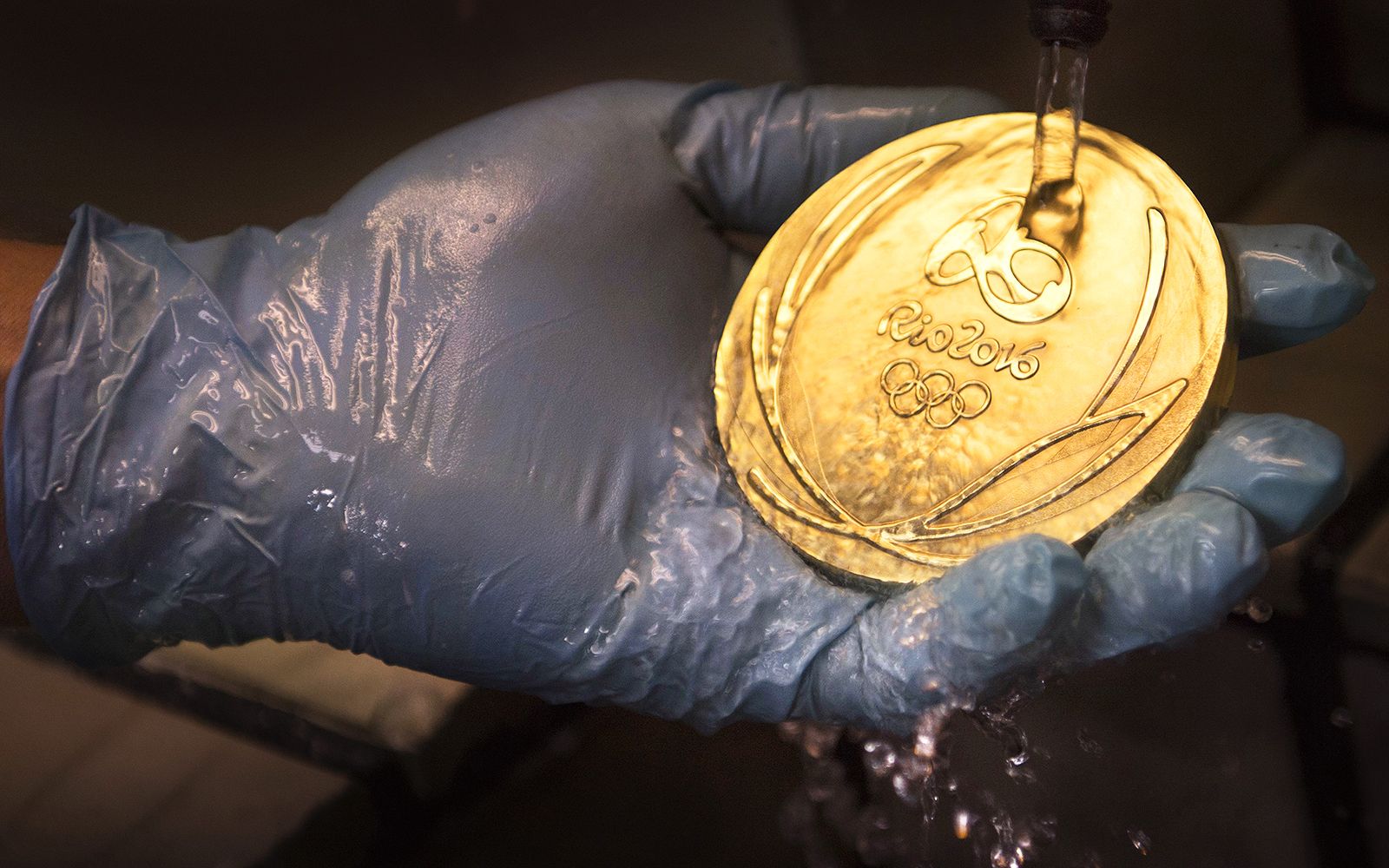

Increasingly, medal standings are being altered based on the contents of refrigerators in Lausanne, Switzerland, where urine and blood samples for performance-enhancing drug testing are stored for up to 10 years and retested with updated methods at the behest of the International Olympic Committee.

Olympic officials and anti-doping advocates tout the ever-lengthening frontier of drug testing as a deterrent and an assurance that they will pursue athletes who dope, even years after the fact and right up to the statute of limitations. But the system for disqualifying those athletes, reshuffling results and reallocating medals is so cumbersome and prolonged that, by the time it plays out, economic and psychic payoffs for the new recipients have long since evaporated.

"There's no way to replace the things that I've lost," said Adam Nelson, a U.S. shot putter who received his gold medal from the 2004 Athens Games in 2013 -- in an airport food court. "It's the memories and the trajectory of your life.

"The reality is that the only people to get punished in the sport from doping [are] the clean athletes." The anti-doping system is fundamentally broken, he added, and lacks "the right people in place to make sure that everybody is held to the same standards."

Canadian cross-country skier Beckie Scott was ecstatic with her 2002 Olympic bronze medal, the first won by a North American woman in that sport. Yet she watched the Russian flag rise with a fatalism about her opponents' improbable performances that had been "part of my psyche for years," she said. She eventually was awarded the silver and then the gold.

Delayed medals never quite add up to full gratification for athletes. Instead, they symbolize the butterfly effect of an altered trajectory. The difference between gold and silver alone can swell to seven figures over a career. Prize money can sometimes be restored, but that's generally a pittance compared to the contractual and commercial opportunities that vanish, impossible to re-create. And there's no way to reconstitute the pomp and emotion of the moment.

An Outside the Lines analysis documented 57 medals that have been stripped due to doping in Summer and Winter Games since 2000, about a year after the World Anti-Doping Agency came into being, although its first harmonized code was still four years away. The largest number of stripped medals, 25, came in track and field. Weightlifting was second, with eight. Three cases involved doped horses in equestrian events.

Only half of the summer sports medalists disqualified over that period had positive drug tests during Olympic competition. The other medals were stripped based on retests up to eight years after the fact, or evidence unearthed by law enforcement (such as in the BALCO investigation) or the scrubbing of a sanctioned athlete's results over a period of time, as was done in Lance Armstrong's case. WADA's statute of limitations is now 10 years.

The number of reallocated medals might be set to explode and, with it, questions about IOC transparency and what really constitutes belated justice for clean athletes who were bilked.

• In June, the IOC announced a "first wave" of 53 positive retests from the Beijing and London Games, then a "second wave" of 45 in July, a far greater number than had emerged from any previous rounds of reanalysis. Olympic officials withhold names for legal reasons until appeals have been exhausted, but there are at least 20 medalists in the first wave and 31 medalists in the second wave. So far, 1,243 samples have been retested, with more to come.

• Weightlifting accounted for 31 of the positive retests, according to official releases by that sport's international federation. Another 13 track and field athletes have been identified in media reports from Russia, Jamaica and Spain. There's no way to know whether track and weightlifting were targeted or are disproportionately represented, because the IOC reveals only the total number of retests and doesn't break it down by sport.

• On July 19, the IOC ordered retesting of samples from the 2014 Sochi Games, a venture that will take place amid revelations of corruption and sample-tampering in the Olympic drug-testing lab. Results of nearly 500 retests from the 2006 Turin Games performed in 2013 have yet to be revealed, and no testing of 2010 Vancouver Games samples has been announced.

Canadian cross-country skier Beckie Scott initially won the 2002 Olympic bronze medal. But two Russians were caught doping, and she was given the silver before ultimately being awarded the gold. AP Photo/Darron Cummings

The one-woman sweep

SCOTT FIRST HEARD she might be upgraded from bronze to gold on the way to closing ceremonies for the 2002 Salt Lake City Games, in a phone call from her coach. Word was that the two Russian cross-country skiers who finished ahead of her in the 5KM Pursuit event had been busted after another race.

"I was shocked because they had been caught," said Scott, 42. "I was not shocked that they had been doping -- obviously that was a given."

Ultimately, Scott completed a unique podium sweep, becoming the only Olympic athlete ever to hold all three medals in the same event at different times. It wasn't the career footnote she envisioned.

Scott, from Vermilion, Alberta, worked her way slowly through the pack in world-class ski racing in the 1990s cognizant of the odds against clean athletes at the top. The Russians, in particular, were too dominant and consistent for belief.

"I know the feeling of someone going by you [as if] you're standing still and looking at the results list and being minutes and minutes behind and wondering, 'What on earth is wrong with me?'" Scott said in an interview in Montreal in May.

The Canadian team deconstructed its entire approach to training, technique, psychology and nutrition after the 1998 Nagano Games. Scott's progress through the ranks gave her hope for a medal in Salt Lake if she had a perfect day, and she did: "The race that I had prepared myself mentally all my life." Her coaches cheered her up the final hill at Soldier Hollow as she made history.

Scott was overjoyed to be on the podium despite her doubts about the familiar faces of the women on the other two steps, Olga Danilova and Larissa Lazutina. "They had always been miles ahead of everyone, and there was no doubt in my mind that it was just another day for them," she said.

Lazutina was disqualified first. Scott received the silver medal at the Olympic Park in Calgary in an October 2003 podium ceremony that included a fighter jet flyover. Both Russians fought their cases as Canadian Olympic officials sought to have their results removed from all events in Salt Lake City -- a move the IOC opposed in arbitration that ground into late 2003. Danilova's medal was formally stripped in February 2004.

Scott was relatively lucky. Her medals were upgraded within two years. The unofficial record for most time between a race and a reallocated medal ceremony belongs to the Nigerian 4x400-meter relay team that finished second to the United States at the 2000 Sydney Games: 13 years.

It took 13 years for the Nigerian 4x400-meter relay team that finished second to the United States at the 2000 Sydney Games to receive the gold medal. Reuters

Jerome Young, who had run in preliminary heats for the U.S. team, was belatedly found to have been ineligible for the Olympics after a previous doping ruling was reversed. That decision triggered marathon legal and bureaucratic wrangling. In the interim, three other U.S. runners originally awarded gold were eventually convicted of doping violations.

The 4x400 saga wound through a transitional time for anti-doping rules, jurisdiction and jurisprudence and probably wouldn't happen again, but it still seems inexplicable in retrospect. By the time the Nigerian runners got their gold medals in the capital city of Lagos, the man who had run the third leg, Sunday Bada, had died at age 42.

Australian racewalker Jared Tallent's upgrade from a 2012 London Games silver to gold took nearly four years because Russian officials played politics with sanctions against the erstwhile champion, Sergei Kirdyapkin, and five other athletes. Kirdyapkin's doping suspension -- a case that did not arise from Olympic competition -- should have been backdated to include the London Games but wasn't. The IAAF filed a successful appeal.

Tallent received his gold medal in Melbourne in June 2016. His wife, Claire, a former elite racewalker who coaches him, estimated his lost income from delayed Olympic and world championship honors in the "hundreds of thousands.''

Like Scott, Tallent had long harbored a conviction that some of his top rivals were cheating. As a 2008 Olympic bronze medalist in the 20-kilometer race, he spoke openly about the suspect coach and training environment of Russian winner Valeriy Borchin (still the official champion but now serving an eight-year doping ban). Tallent got so much public and social media backlash that he regretted his honesty. In a finish line interview in London, he called Kirdyapkin "a true champion," but he now says he wouldn't hesitate to speak up again.

"The big thing that needs to change at the minute is that it shouldn't be left up to the countries and national anti-doping bodies to dish out the doping bans," Tallent said. "There's obviously clear conflicts of interest and corruption that can be had there, and that's what happened in my case."

IOC president Thomas Bach's Agenda 2020, a slate of reform proposals, calls for "formal ceremonies" to honor athletes who receive medals after competitors are disqualified for doping, but what shape those would take remains imprecise. That leaves national Olympic committees or federations on their own.

Scott's gold-medal celebration took place in June 2004 on the steps of the Vancouver Art Gallery. She teared up when the 500 people in attendance sang "O Canada." The mother of two, who served on the IOC Athlete Committee before taking a similar role with WADA, said she has never made a real stab at calculating her monetary losses.

"I think the bureaucracy that follows once the revelations are clear can definitely be sped up and expedited, and it should all be with the interest of the clean athlete at heart and making sure the experience is as close to the Olympic Games as possible for them," she said. "It's true as time goes, people forget -- it becomes increasingly less meaningful."

In the 2004 Games, Adam Nelson thought a foul on his last shot put throw had cost him the gold. Nine years later, though, he was declared the winner when the gold medalist was caught for doping. Andreas Rentz/Bongarts/Getty Images

The lifetime achievement award

ADAM NELSON, an entertainer and a believer, couldn't have asked for a better stage than the one he got at the Athens Summer Games: The ancient Olympia Stadium, used in the first Olympic Games in 776 B.C., with its pitted stone archway and sun-baked dirt track. Men's and women's shot put were the only competitions held there in 2004.

"You kind of get there the first time, you look around, it's like, 'Oh my gosh, this is the birthplace of this whole movement that certainly inspired me for 20 years of training,'" said Nelson, who focused on the shot put after playing football at Dartmouth College.

For once, his "silly profession" had been singled out for special attention. Spectators sat on the grassy slope alongside the 700-foot-long rectangle and watched the big men roar.

Nelson understood early on that most people thought his sport was dirty top to bottom. He couldn't really blame them, but he maintains it is possible to win clean. His father gave him little choice, telling Adam he'd disown him if he cheated.

On Aug. 18, 2004, Nelson, a runner-up at the 2000 Olympics and the previous two world championships, led for most of the competition. The gold medal came down to the final throw. Yuriy Bilonog of Ukraine had the edge.

Nelson spun around, a thatch of thinning blond hair flying upward, and released. The steel ball thumped in the dust. "No! No! No!" Nelson hollered hoarsely. "That was not a foul!" He waved his arms, yelling and half-pleading with the judges in their blazers and straw hats. The replay showed otherwise -- his right foot had strayed over the line.

U.S. shot putter Adam Nelson and Canadian cross-country skier Beckie Scott were robbed of their proper Olympic medals due their competitors' use of PEDs. Nelson and Scott share their nontraditional routes to gold.

Bilonog was already doing his victory lap, high-fiving small children, his country's flag in hand. "Another silver for Nelson," the NBC commentator intoned.

Nelson suspected Bilonog wasn't clean, but that day, "I wasn't angry at him, I was angry at myself," he said, sitting in his living room in a different Athens -- his longtime home of Athens, Georgia -- thousands of miles away. "The anger at everyone else came later."

He came home and tore up almost an acre of land with a steel rake, exorcising the experience with manual labor. Over the ensuing days, weeks and years, rumors abounded that Bilonog had tested positive. Those rumors didn't pay Nelson's bills. He estimates that the difference between gold and silver cost him as much as $2.5 million during his career.

"I was branded, basically, the first loser, and so it devalued every potential opportunity I had to make this a profession," he said.

Nelson channeled his anger into competition and creative marketing. He wore "Space For Rent" T-shirts at events and auctioned himself to sponsors on eBay. He won the 2005 World Outdoor Championship -- the only major title he was able to celebrate in real time. He married, made another Olympic team in 2008, had two daughters and went bald.

Bilonog's positive test for oxandrolone metabolite, an anabolic steroid, surfaced when the IOC retested his "A" urine sample in July 2012 -- just before the expiration of what was then an eight-year statute of limitations under the WADA code.

That triggered a complicated bureaucratic dance between the IOC and the international federation. A different three-person IOC Disciplinary Commission appointed for each case rules on doping violations found in retests, but doesn't strip and re-award the medal until the sport's governing body (such as the IAAF in track and field) officially alters the results. From Rio 2016 onward, the Court of Arbitration for Sport will handle all doping cases that arise from in-Games positive tests or re-tests.

It took another four months to test Bilonog's "B" sample. He had the right to be present and asked for a postponement. A technical issue at the WADA lab in Switzerland dragged things out further. In October 2012, according to the IOC's written ruling, Bilonog "alleged that he had no more vacation days and that his employer would not give him the permission to leave his work." He did not attend or present a defense at the IOC Disciplinary Commission's hearing.

Nelson said he bears no ill will against Bilonog, even though the Ukrainian also beat him in a previous meet where a $1 million series bonus was at stake. "I think he was a soldier," Nelson said. "I think he was doing what he was told. I don't think he was given a choice."

The IOC issued its ruling on Dec. 1, 2012. The IAAF revised the results. The IOC reallocated the medals in May 2013. Thus, a competition that had begun nine years before in surroundings evoking antiquity ended in a modern flurry of paperwork.

A reporter informed Nelson he was the official gold medalist. "It's kind of like winning a lifetime achievement award posthumously," he told his wife.

He wouldn't put his silver medal in the mail. A USOC emissary met him outside a Burger King in a food court at the Atlanta airport and swapped it for the gold.

U.S. track officials have tried to restore part of his irretrievable moment with presentations on two occasions, most recently at July's Olympic track trials in Eugene, Oregon, before a crowd of about 12,000. Nelson struggled for composure as a lone trumpeter played the national anthem that evening. He deserved the gold, but it still doesn't feel like his. He kept it in the glove compartment of his truck for a while, then in a utility drawer.

He loves to show the gold medal to kids and he understands that it elicits a visceral reaction, but he's not sentimental about it. "I want this medal to be an instrument of change," he said. "With regards to the anti-doping movement and to me, I represent either the greatest failure or their greatest success. In the last four years, it's been extraordinarily frustrating to see them not doing anything different."

U.S. runner Alysia Montano has no idea how long it will be before she finds out whether she's the official 2012 Olympic 800-meter bronze medalist.Two medalists ahead of her have been implicated in doping but have not yet had their medals stripped. Stu Forster/Getty Images

The daily battle

NEW WADA DIRECTOR general Olivier Niggli told Outside the Lines he felt "divided" about a system that often results in lengthy delays for rightful medalists. "I feel really sorry for the athletes who, because of [doping], didn't get their moment on the podium," he said. "But for the anti-doping fight, I think in some way it's not a bad thing, so that everybody knows that getting your medal is not the end of the story and if you're cheating we will be going after you."

U.S. runner Alysia Montano is still waiting for the postscript of the Olympic 800-meter final held on Aug. 11, 2012, in London. The women who finished in first and third are taking another, much slower lap through scientific, legal and bureaucratic protocol on a track Montano can't see.

She has no idea how long it will be before she finds out whether she's the official bronze medalist, so Montano tries not to dwell on it. She has permitted herself to dream of a White House ceremony where President Barack Obama would present it to her.

But, like Nelson and Scott, she knows something irrevocable was lost.

Montano wept in the interview pen in London four summers ago after finishing fifth. The tears seemed completely natural for a competitor at the pinnacle of her sport, crushed by disappointment. Yet that emotion was just a fraction of what she was actually feeling.

She found Russian winner Mariya Savinova's finishing kick unbelievable. She felt certain Savinova and teammate Ekaterina Poistogova -- who also blew by Montano in the stretch to win bronze -- had doped. Montano never considered saying that to reporters. She had no tangible proof. It would sound like an excuse. Saying it aloud could further corrode her belief that she would beat cheaters on another track on another day, a conviction she needed to keep going.

Montano, 30, dusted herself off and tucked her trademark plastic flower in her hair. She ran the 2014 national championships 34 weeks pregnant to make a point about strength and stereotypes.

Confirmation of her suspicions first arrived in late 2014, when a German television station aired admissions of performance-enhancing drug use by Savinova and Poistogova -- footage secretly recorded by Russian doping whistleblower Yulia Stepanova. In November 2015, Part I of WADA's independent commission report recommended lifetime bans for both medalists.

Montano's phone rang off the hook. She felt elated, vindicated, frustrated. And then she just felt devastated.

"I had a good four or five days where I was on fire, and then I couldn't get out of bed," she said in early June, sitting in the sunny courtyard of a favorite coffeehouse near her home in Berkeley, California. "Grief hits. I felt like I was in mourning for two weeks.

"At this point, it is really exhausting, it's depressing to relive it, and then to have to pick myself back up over and over again. I've kind of put myself in a lot of different emotions dealing with this issue, from the time that I suspected to the time that it's been shown to be true to where we are right now."

It's not as if London were a one-off. Savinova won the 800 at the 2011 world championships and took second place in 2013. Montano finished fourth both times. After the WADA findings emerged, she tried to calculate the difference three prestigious podiums would have made in her career. When the math hit $1 million, she stopped.

Montano scrolled through her phone, showing the entries she makes in the online "whereabouts" calendar so drug testers can find her. Miss three tests and you're out. Athletes from Kenya and Ethiopia, where testing has been dubious for years, have finished ahead of her, too.

"It kills me when we find out [the] infrastructure's not even in place in other countries, and they're allowed to compete in the same level I am, and I'm held accountable," she said.

Here is what Montano wants people to understand. Sure, she'd like to have her belated medal presented by the first African-American U.S. president. She wishes her grandmother, who died after the London Games, could enjoy the moment. She'd like a way to recoup her financial losses.

But what she wants most is for the anti-doping system to do its job as assiduously as she does hers. She wants to be free of the "psychotic, almost bipolar battle" she says she and other athletes wage daily, trying not to let doping rent space in their heads.

She wants cheaters to be caught before they get into the starting blocks at the Olympics, so that phantom finish line, that holographic podium shimmering in some sterile laboratory somewhere far from the Olympic infield, moves closer to the present where it belongs.

At the 2016 U.S. Olympic trials, Montano fell after colliding with another runner on the final turn of the 800-meter final. Bill Frakes for ESPN

Epilogue

IN THE WAKE of the WADA-commissioned McLaren report presenting strong evidence of state-sponsored doping in Russia and a conspiracy to fix lab results at the 2014 Sochi Games, Beckie Scott and other members of the WADA Athlete Committee called for all Russian athletes to be barred from participating in the Rio Games, which start Aug. 5. The IOC decided against a blanket ban. Russia's track and field federation remains suspended, but a significant number of Russian athletes in other sports will compete.

A week before his 41st birthday in July, Nelson competed at the 2016 U.S. Olympic trials and finished seventh. He was presented with the 2004 gold medal in a third substitute ceremony the same day.

Alysia Montano fell after colliding with another runner on the final turn of the 800-meter final at the 2016 U.S. Olympic trials. She hobbled to the finish, crumpling to the track several times on the way in tears. The two Russians who finished ahead of her at London 2012 have yet to be officially sanctioned for doping. Their names still appear in first and third place.

Olympics medals research by Charlotte Gibson and Ashley Melfi.

Investigative reporter T.J. Quinn and producer Andrew Lockett of ESPN's Enterprise/Investigative Unit contributed to this story.