One Giant Leap

Nathan Chen, the Quad King, has figure skating's most daring move down cold. Will he take the sport to new heights at the Olympics?

One Giant Leap

Nathan Chen, the Quad King, has figure skating's most daring move down cold. Will he take the sport to new heights at the Olympics?

ESPN THE MAGAZINE • 02/08/18This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Feb. 5 State of the Black Athlete issue. Subscribe today!

Nathan Chen paces in the mouth of the rinkside tunnel at the 2018 U.S. Figure Skating Championships in San Jose, California, the only man with an Olympic slot secured. He can belly flop and be named to the team based on his previous results. But that isn't the point.

He arrived at nationals in January sponsored by Coca-Cola, Bridgestone, United Airlines, Nike and Kellogg's, and dressed for competition in a palette of black, white and charcoal designed by fashion icon Vera Wang, who also directed him to lop off his raffish curls to match her sleek, modern style. He'd won all four international events he entered this season, surpassed only by the specter of his breakthrough at the 2017 nationals. At times it seemed Chen had advanced the plot so fast that even he couldn't keep up.

An increment of brilliance had eluded him in the year since he became the first athlete in the world to land five quadruple jumps within a 4-minute, 30-second free skate. Chen's five-quad coup would've been inconceivable not so long ago. Most of the top U.S. men had tried just one that night.

The only suspense: Can the 18-year-old equal his own standard? Chen had been sick over the holidays and missed more than a week of training. He needs to feel the sweet impact of clean landings and clear the maybes from his mind. His goal is to peak in Pyeongchang, but this is his highest intermediate base camp, the last chance before the Games to prove 2017 wasn't a one-off.

As Chen emerges on the ice, a kids brigade scoops up plush toys tossed in homage to the previous skater, gradually leaving him a blank canvas. He strikes his opening pose. From the stands, 1988 Olympic champion Brian Boitano glances at a close-up of Chen's face and thinks, "He's there."

Thirty seconds in, Chen unfurls an enormous quadruple flip/triple toe loop combination -- a demanding and high-scoring opener. When he hits a second quad, and a third and a fourth and a fifth, the crowd exhales in collective acclamation. Check, check, check, check, check. The most taxing part of the program is behind him, but not the most vexing. On an attempted triple axel, Chen abruptly releases midair and "pops" the jump, in skating parlance, landing after one rotation.

He takes a few deep breaths when the music ends and runs his hand through his hair as he glides in a small circle, allowing himself a moment of relief. His coach, Rafael Arutunian, picks up a stuffed tiger in the kiss-and-cry area, where athletes wait for scores, and shakes it triumphantly in Chen's direction, then pats his back when the two sit down.

"Three days' practice," Arutunian tells him. "On three days' practice." Chen nods, looking spent but pleased. His combined score for the short and long programs is 315.23, putting him 40 points beyond the next man.

"And he did it in a pressure situation, and he did it while skating last, and, and, and," Boitano says the next day, after Chen has been officially named to the Olympic team. "The guy is a monster."

Skating has rarely beheld a more gargantuan talent, faster learner or more ardent self-critic than Chen. Without diminishing the honor of representing the U.S., Chen concedes that winning nationals and clinching an Olympic berth were simply what he expected of himself. "Honestly, at this point, it's sort of just checking off that box," he says after the announcement. "I still have a lot of work to do."

Chen, made for the moment in San Jose, was already figuring out how to handle the next one.

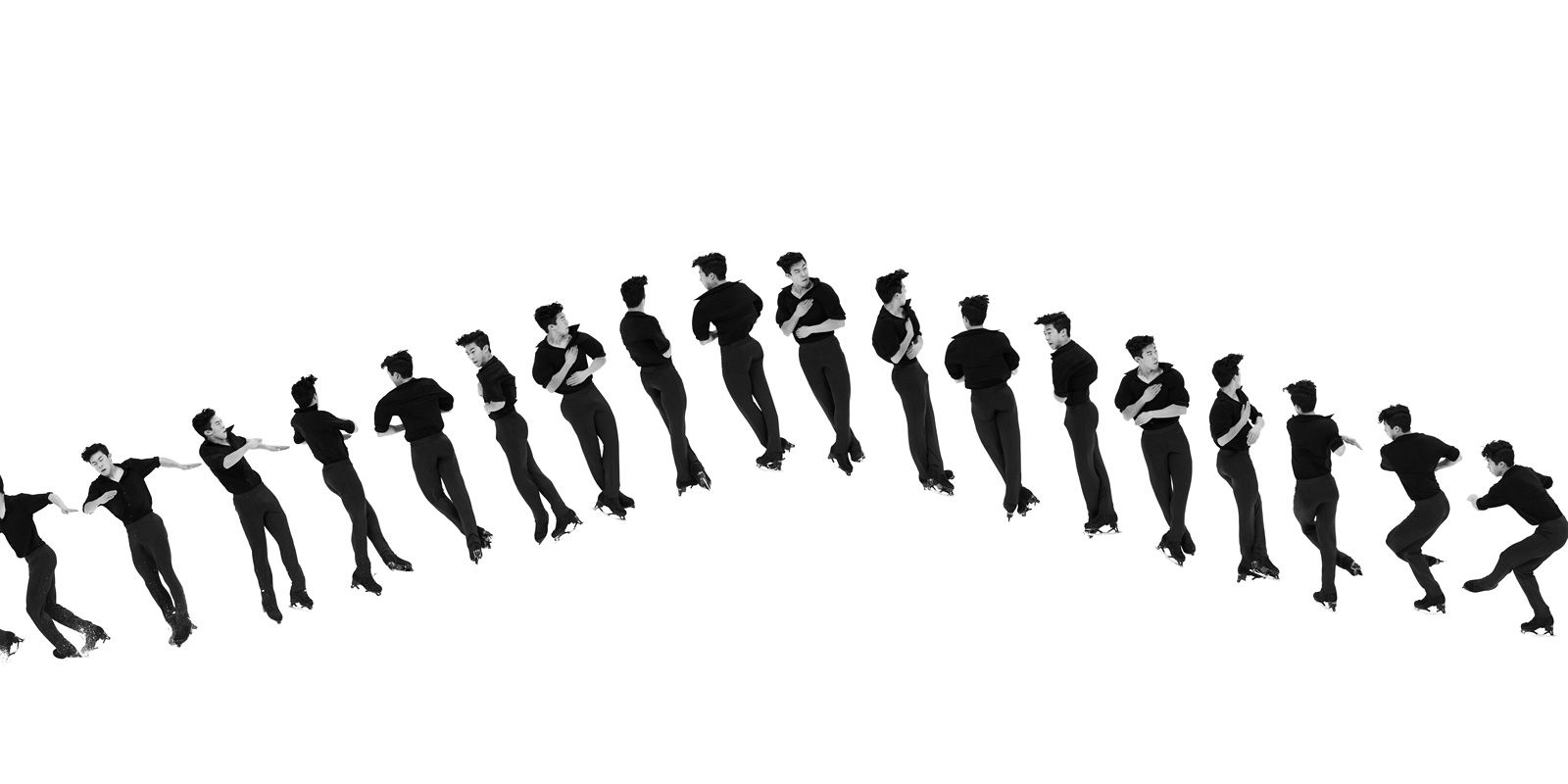

For a quad, skaters typically jump 18 inches off the ice at a velocity of 11 feet per second to reach 450 rpm. All in 0.6 of a second. Chen centers his hands on his torso and pulls his elbows in for an upright and narrow silhouette.

"He gets into position quickly, which buys him more time to rotate, and he gets very tight. His arms are right against his body. There's minimal separation between his legs. You can draw a straight line up his body." -- James Richards, kinesiologist

As a child, Chen juggled dance, gymnastics, piano, violin and ice hockey, sharpening a natural work ethic and focus. When he says he views each competition as a learning opportunity, he means it.

"His approach to the process is so cerebral, constantly assessing what's happening to him and his environment. He does the homework himself and supplements it with material gleaned from coaches and teachers." -- Peter Christie, ballet instructor

Shock absorption on landing is crucial for injury prevention and recovery. Chen cushions the impact with slightly bent knees and very likely front-to-back flexion of his ankle within the boot.

"He has phenomenally soft knees. He lands like a butterfly. I'm sure if I measured his impact, it would be lower than average. He's graced with a slight frame. Narrow people have the ability to spin faster. He has it all." -- Kat Arbour, off-ice training specialist | Photos by John Huet for ESPN

Quads remained part stunt and a whole lot of Hail Mary for much of the 30 years after Canada's Kurt Browning first landed one in competition in 1988. "For them, it must just be a jump," Browning told the National Post newspaper recently, describing the current generation. "For me, it was the first guy to fly across the Atlantic."

Men began to focus on the quad in 2005, when a new scoring system offered more reward for the risk. For a while, skaters such as 2010 Olympic champion Evan Lysacek, who won without a quad, could still prosper on triple jumps and artistry. But now quads are necessities rather than luxuries for elite men.

According to 2002 Olympic bronze medalist Tim Goebel, a quad pacesetter of his era, video analysis and better training techniques have helped today's skaters start rotating sooner after launching from the ice. But part of the surge could be psychological, he says: "All it really took was for one or two to start landing the flip and lutz, and suddenly half a dozen of the men are landing them, at least in practice."

Chen has distinguished himself by twice landing a total of seven in one competition and has successfully executed five different kinds of jumps. He likens the exertion of a quad to weightlifting and tacking another rotation onto a triple jump to "adding a hundred pounds to your bar." Slight and strong at 5-foot-5 and 134 pounds, Chen has an ideal build for his vocation, but his biomechanics and perfectionist mindset are what make him a revolutionary figure.

He spins faster and more efficiently than other skaters because he snaps his arms, legs and feet into a tight, centered corkscrew faster than most. He cushions landings with the proper bend in his knees and ankles, helping him recover from the jolt and continue his program seamlessly. As the extraordinary has become routine, simply surviving a quad is no longer enough. Skaters are expected to connect with their music going into and coming out of one.

But no young skater endures that many landings unscathed. Chen's most serious setback came just after he won bronze at the 2016 nationals. Early in his number at the postcompetition gala, he jumped awkwardly and clutched his left hip on impact, grimacing in pain. Part of his pelvic bone had splintered, pulled away by a muscle or tendon. He didn't fall but slowly skated, bent over, to the side of the rink. He left the arena in a wheelchair and underwent surgery that would sideline him for months. It was a vertiginous trip from high to low.

He told his childhood coach, Stephanee Grosscup, "I went into a deep, dark hole. Nothing makes you stronger than crawling out of that darkness."

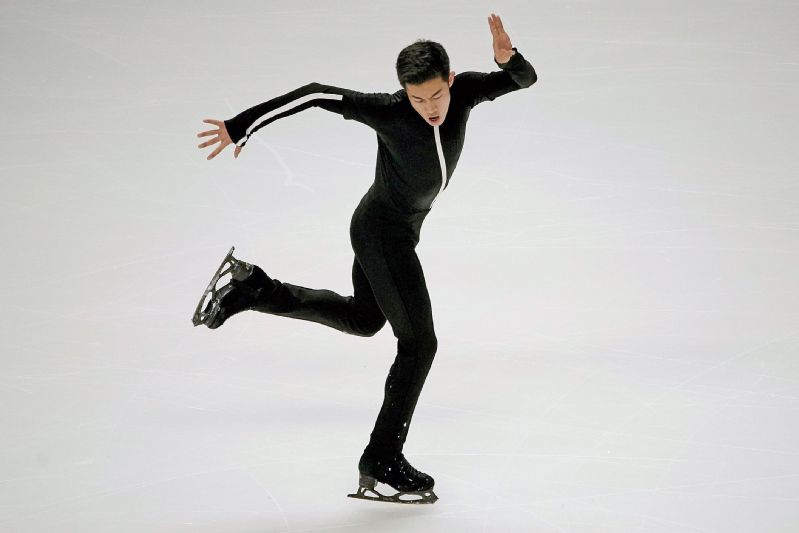

Chen's biomechanics and perfectionist mindset are what make him a revolutionary figure. Atsushi Tomura/ISU/Getty Images

A baby skater boom hit Salt Lake City in the months after the 2002 Winter Games. Hundreds of kids signed up for beginner lessons at the new rink where Olympians had run through practice routines. The ice seemed to hold crystallized ambition.

Nathan's older siblings already skated: Brothers Tony and Colin played hockey, while sisters Alice and Janice had roles as "Children of Light" in the Olympic opening and closing ceremonies. They'd amuse themselves by bundling their youngest brother in the fuzzy white costumes they got to keep.

When Nathan wobbled onto the ice with a dozen other toddlers for Grosscup's "Snowplow Sam" class, he was so tiny that she had to lower herself into a full knees-by-shoulders squat to talk to him at eye level. He gazed back at her with a startling directness.

"I'd say, 'We're gonna do the one-foot balance! Or the forward fish!'" Grosscup recalls. Nathan never spoke. He just turned around on his hand-me-down skates and did exactly what she asked. "I remember going home that night and thinking, 'Wow. I think I just ran into a prodigy, a young balance master,'" Grosscup says, sitting in an interior stairwell at the SAP Center in San Jose before Chen's free skate at nationals. It is the only spot quiet enough for talking as the crowd swells to watch her former pupil.

At the end of the six-week session, Nathan's mother, Hetty Wang, approached Grosscup and asked whether her son might benefit from private lessons. The two women didn't know it, but they were about to make a pact that would jump-start an Olympian. Mindful of the family's modest means, Grosscup often charged only half her normal fee or asked for a home-cooked dinner instead. "I'd teach him a couple times a week, and then Hetty would go out there with him in public sessions, chase after him to make sure he was doing all the drills, all the warm-ups, all the edges, all those spins over and over again," Grosscup says. "Incredible, phenomenal devotion."

Chen's parents met in China and moved to Salt Lake City in 1988 when Zhidong Chen, a pharmaceutical scientist, began graduate studies at the University of Utah. His wife was trained as a medical translator. They moved to a home southeast of downtown, where Hetty hung a big wall calendar by the door and filled the squares with the constant comings and goings to music, dance and sports practices.

Nathan's education included several years of training at the Ballet West Academy, where he performed in productions of Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty with the professional company. He had a gift for midair rotation and could do a double tour -- two full spins from a standing leap -- at age 8.

"I don't know if I could ever say that I saw him having a hard time doing something," says former Ballet West Academy director Peter Christie, now director of education and outreach, who worked with Chen in the dance studio and on the ice.

Nathan excelled at almost everything he tried except perhaps playing goalie against his brothers, who winged shots at him in the basement until the net sagged off the frame and plywood had to be installed behind it to protect the wall. His focus eventually narrowed to figure skating, but all that he'd absorbed -- fluidity and character portrayal from dance, an ear trained by lessons from a world-class pianist, the body control required by gymnastics, the toughness of hockey, the discipline and time management of a packed schedule -- wound up being a means to an end, contributing to who he is now.

"Oftentimes, you watch a skater's routine and you could take what they're doing and insert any kind of music you want. It wouldn't make a difference," Christie says. "With Nathan, you watch it, and his choreography and his execution really is reliant on his relationship with that music."

Nathan's first competitive programs were set to instrumental versions of "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" and "Three Blind Mice." Grosscup led the 4-year-old through his first bunny hops and told him to imagine he was squeezing a giant marshmallow when he did spins. At age 10, under Russian-born coach Genia Chernyshova in 2010, Nathan became the youngest-ever U.S. champion in the novice division. "I have a very aggressive style, and he liked it," Chernyshova says. "Some people are 5 going on 30, and he was one of those. It worked for him."

Interviewed by ABC after that first national title, Nathan spoke with a matter-of-fact composure that has since become familiar. When asked on air whether he'd be at Sochi in 2014, Nathan politely explained that he'd be too young but thought he could be ready for the 2018 Olympics. With enough speed and the right timing, Nathan said, the jumps came easily.

At the 2018 nationals, Chen landed seven quads over two programs to ice a second straight gold. Stan Szeto/USA TODAY Sports

In mid-September, former U.S. champion Max Aaron stands on the concourse above the ice where Chen learned to skate. The two men are competing in an early-season knock-the-rust-off event in Salt Lake City. The occasion feels fitting and momentous: Chen will debut his Olympic programs where he once tooled around the rink in a mouse costume.

Aaron's expectations, along with everyone else's, are outsized. "What the kid is doing is un-buh-lievable," he says. "It really is. When I'm practicing with him, he just does not miss. You're just saying, 'Are you ever gonna fall?' It's superhuman."

The 25-year-old Aaron is one of several Americans left feeling merely mortal in Chen's wake. Aaron won the junior national title in 2011 at age 18. Chen won it the next year at 12. Aaron landed three quads on the way to the 2013 U.S. senior title at age 20. Four years later, Chen landed a record seven to win it at 17.

Chen's work ethic and modesty have endeared him to many, including Aaron, who pauses for breath and uncorks more superlatives: "The technique on him -- unbelievable. The mental side on him -- unbelievable. He can be the guy. He can do a total of nine. Nine-quad guy. That's gonna be him. I'm calling it now. And he'll be the first guy ever to do quad-quad. Quad-quad guy, nine-quad guy, I'm calling it."

But Chen played the long game this season, sometimes describing his programs as "watered down." He is a mere four-quad guy over two programs in Salt Lake City, winning without breaking a sweat. He and Arutunian tinker with the order and pattern of the jumps, deciding which ones to do when he's fresh and which ones he can pull off when his energy is depleted late in the program. (The quad loop, which he successfully lands for the first time in Salt Lake City, is deemed too risky and ditched later in the season.)

Until nationals, Chen competed wearing simple black pants and a solid shirt, sparking curiosity from the trade press, which wondered when he would bring on the glitz. There was a similar ratcheted-down aura about him in competition for much of this season, especially in his intricate, evocative free skate, set to music from Mao's Last Dancer. Was he conserving energy? Spread too thin by Olympic hype? Were quad repetitions catching up with him?

At the Skate America Grand Prix event in late November, Chen racks up the biggest short program score of his career despite a nick in one blade. He swaps it out before the Saturday afternoon free skate, but his psyche seems dented as well.

Chen nails two quad lutz jumps but puts his hands down on another quad, falls on his triple axel and uncharacteristically pops two more jumps as the crowd gasps and murmurs anxiously. He scrunches his face in displeasure at center ice after the music stops. Eleven weeks before Pyeongchang, he has just logged his worst outing of the season.

Chen's usual manner at news conferences occupies a narrow range between stoic and serene, with occasional flashes of dry humor. This time he stares ahead, looking hollowed out and confounded even though he had won on the strength of his short program. It is the face of a teen who has relentlessly rehearsed everything except temporary mortification. "I definitely have had days like this in practice," he says. "But those days obviously aren't important, aren't on the same level as a competition or Grand Prix. This is a totally new experience for me."

Arutunian whisks him straight to an evening practice so the sensation won't fester. He and Chen share a conviction that work heals all wounds. "Trained very well," the coach says the next morning, leaning back equably in a folding chair at the rink. "Everything looks better. We had some issues with boots, blades, preparations, did some mistakes, professional mistakes, again because of some more miscommunication."

A protective tone edges into Arutunian's voice. "Everybody now likes Nathan," he says. "Who was liking him before? He now sits in press conferences; he cannot give [individual] interviews because so many people want to talk to him. Who was talking to him two years ago? Who was believing that would happen? I knew. We don't count year to year; we count every four years. Do you understand that the day after the Olympics, he gets four years older?"

Quad Squad

A rule change in 2005 made quads an essential jump for top male skaters, as seen by the increasing number of quads attempted by the top three men at Worlds and the Olympics since. No one lands more than Chen.

The morning after the free skate in San Jose, Chen walks out from behind a black curtain and takes a seat on the dais before a roomful of reporters, first in alphabetical order of the three men selected for the Olympic team.

He'd had a buildup that would have been exceptional for any other skater. He'd done myriad things right. He'd pulled off one of the most difficult challenges in the sport -- chasing himself around the rink and winning when he wasn't at his best.

He acknowledges his accomplishment and his pride. Then Chen unflinchingly describes the moments after he and his mom received the official word from U.S. Figure Skating. They went straight to the sore spot -- the triple axel.

"That was definitely the center of attention: 'That was your one mistake; what can you do to fix it? Why did you make the mistake?'" he says.

Chen elaborates later to ESPN: "She knows that I basically understand what I've already done well; she knows that I don't need a reminder on that. She knows that I need someone who consistently tells me things I need to improve on and makes me a better skater in general."

The triple axel gives Chen more trouble than most quads, which might seem counterintuitive, but he is not alone. Skaters are creatures of habit. The axel is the only jump with a forward entry and a backward landing, giving it an extra half-rotation.

Forward is Chen's default direction in most other ways. He dislikes breaking down video of his old competition programs, preferring internal visualization and working through problems on the ice. Having known nothing but accelerated development, Chen says he isn't concerned about conquering his nemesis in the short time before Pyeongchang. The triple axel would come. "It's very technical; just definitely gonna put more work into it, more time analyzing it," he says.

He can grow his hair back come spring. In the meantime, he'll defer to Vera Wang's attention to detail. "She wanted the full package, everything to be very clean, very sharp, since that's what the programs entailed," he says of his curls. "But I just didn't want to mention it and see if it was brought back up again. Hoping that she would forget. But I knew she wouldn't."

The time when everything is a means to an Olympic medal will end soon. Chen plans to balance skating with college in the fall. In November, he posted a photo to Instagram showing him shooting hoops under moody skies on a court near Long Beach, California. The caption: "This word is commonly referred to as life."

For now, there will be more weight than ever on the bar and no guarantees hanging in the vacuum created when his blade scrapes and the Pyeongchang crowd inhales.

Header Photo Sequence: by John Huet for ESPN