The Third Coming Of Derrick Rose

Two reconstructed knees later, the former MVP isn't the same man he used to be. And that's the point.

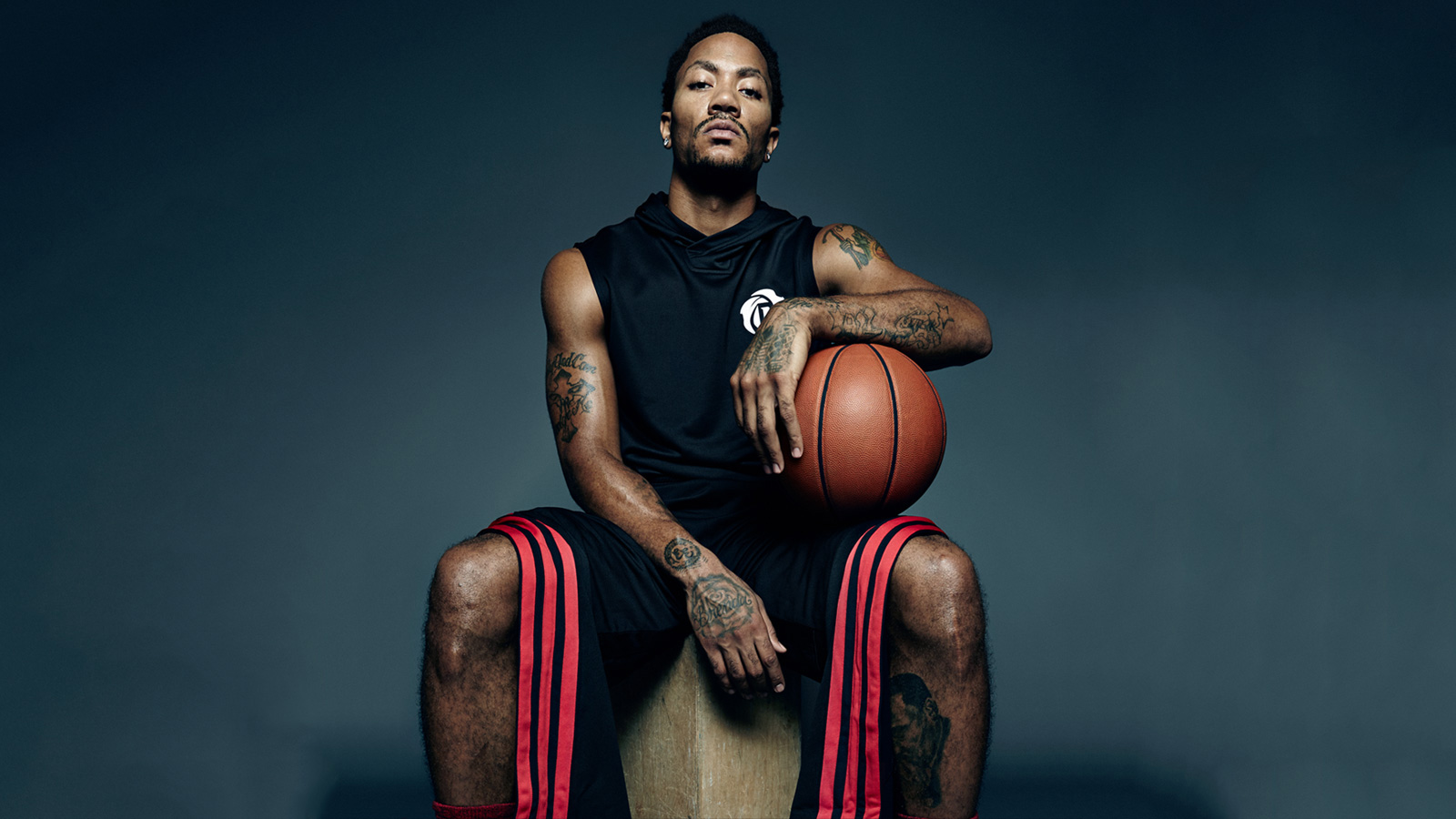

THE LIFE DERRICK ROSE wants back is three days away, and not a thing in the world but time can bring it any closer. He must endure a little more, leaning against the wall in the corner during a break in a photo shoot, alone, doing calf stretches then touching his toes. When action in the private gym resumes, he won't dunk, rising until he hears the shutter click, then tucking the ball and landing as softly as he can. That's one of the many lessons he learned during his time away. Every dunk costs something, a debt that will demand payment months, even years, from now. He's about to turn 26. He wants to save his legs.

"Everything is starting up," he says, bracing for what's to come.

It's a Friday in late September. The Bulls report for preseason in 72 hours. The question of the past three years -- can he return to his career previously in progress? -- will soon have an answer, which everyone close to Derrick wants to hear, even if that answer is no. A cycle of injury and recovery finally has an end date, a month ahead and closing fast.

"Where's the first game?" his agent, B.J. Armstrong, asks, watching the action. "New York?"

Randall Hampton, Derrick's best friend since sixth grade and now his assistant, smiles.

"Yeah," Hampton says, "then Cleveland."

INERTIA SMELLS LIKE fried perch and chicken wings covered in that odd South Side concoction known as mild sauce. Reggie Rose, like everyone in his brother Derrick's small inner circle, is waiting, and at this particular moment he's waiting on his order at Harold's Chicken Shack No. 55, in the middle of a tour of Englewood, their old Chicago neighborhood. They've all gotten very good at waiting; today, a Thursday, is the 880th day since Rose blew out his ACL and began his rehab, punctuated by a torn meniscus a year and a half later. Reggie has been counting the days, watching him struggle to heal.

"His thing is wanting to be the same," Reggie says.

Reggie finishes lunch and drives away, eventually making his way east on West 63rd Street. Thirteen years older, his domineering presence kept Derrick from being picked apart by the Gangster Disciples who controlled their neighborhood, then the parasitic runners and gatekeeping NCAA officials who controlled the avenues and mechanisms of escape. Nothing, not drug dealers or money-hungry basketball pimps or amateurism-guarding schoolmarms, would keep his brother stuck in Englewood. Traffic is thin as he crosses Halsted Street, with Kennedy-King College looking modern and alien at the intersection. Everything else is plywood and blight.

"You know what?" Reggie says, turning thoughtful, surrounded by reminders of his past. He thinks about Derrick, and how three years ago, his then-22-year-old brother was innocent and unafraid, the most valuable player in the NBA.

"He knows that he will never get back to that," Reggie says.

That's the admission everyone has been digging for, but that's not what he means: The new Derrick Rose is explosive and aggressive, but he's coming back like Eve came back from the apple, mining intellectual and emotional depths he couldn't have imagined when he first hurt his knee. He's different now, for sure, maybe for better, maybe for worse. The old Derrick Rose is a casualty of the two injuries and the knowledge that came with them.

"He's gone," Reggie says, and he sounds a little melancholy.

text

Peter Hapak; Hair: Simeon Dill; Makeup: Karen Brody

THIRTEEN MILES SEPARATE Derrick Rose's apartment at the Trump Tower above the Chicago River and his boyhood home at 7305 S. Paulina St. When he's longing for something he can't articulate, perhaps a reminder of what he's gained, or maybe what he's lost, he gets in his car and makes the drive: often the E-Way to 57th Street, Garfield over to Ashland, then Ashland up to the Murray Park section of Englewood. When he arrives at his old house, he slows down but never, ever stops, turning back onto Ashland Avenue and accelerating toward his new life among the skyscrapers and meat palaces of downtown.

At one of those meat palaces this summer, sitting around a table upstairs, Derrick tells Reggie and Randall about his recent vacation. He got home two days prior from Sag Harbor in the Hamptons, one last breather before the most important basketball season of his life. At the end of his trip, he withdrew, full of tension, moving around the rented house like a ghost. When he's relaxed, he's hilarious, his tough magazine-cover frown replaced by a boyish grin, softening all his features. But when he's focused, he becomes quiet and shy. With the season staring him in the face, Derrick didn't feel like talking. His girlfriend noticed him turning inward. Seven hours before leaving the Hamptons, he texted Randall back in Chicago: He wanted to shoot when he got home.

Rose's private plane landed at Midway Airport, and a little while later he walked into his apartment high above the city. Sometimes he stands at the floor-to-ceiling windows and thinks. He can see his old neighborhood from his living room, and of all the distances people measure in their lives, such as the 30 months since he tore his ACL, this is the distance that matters the most.

He knows what is happening down there in the dark.

In the month before Derrick left for vacation, 68 violent crimes were reported in Englewood alone, and 49 of them occurred on the street or sidewalk. Almost every night, someone gets shot in the neighborhood, and the murders fill the pages of the Tribune and Sun-Times. It is not safe to go outside. Four months ago, the city reeled when a 14-year-old girl named Endia Martin was murdered, not by a stray bullet but in cold blood by another girl in a Facebook dispute over a boy. A South Side church filled with mourners. Before the service, Rose drove down and quietly went inside the sanctuary to pay respects to the parents, leaving again just as quietly, not wanting to create a scene. He just wanted them to know he too was mourning the loss of their little girl. When they looked up and saw Derrick, their eyes widened, because 13 miles south from his new life, he isn't a person but an idea, proof that better days might be ahead.

His mere presence embodies the idea of escape.

Rose has gotten very good at waiting in the 880 days since he blew out his knee. Peter Hapak

ALL DERRICK ROSE ever wanted was a new life for himself and his family. The desperation of that dream is often minimized in its retelling because the ghetto escape story is such a worn plot twist in the sports myth machine that the hopelessness of an urban slum is seen as an obstacle like any other, such as, say, a knee injury. He lived at the center of a limited, shrinking world.

Ask Derrick where he's from and he'll say, "Chicago."

Ask what part and he'll say, "South Side."

Ask what part and he'll say, "Englewood."

Ask what part and he'll say, "Murray Park."

Murray Park runs eight short blocks east to west, four longer blocks north to south: 71st to 74th Street, Ashland to Damen Avenue. The defining memory of growing up in a place like this isn't the violence, poverty or fear, but the oppressive and daily presence of limitations. The 71st Street boundary stood like an international border. On the other side, a rival set of Gangster Disciples controlled the area around Raster Park. Nobody crossed without permission. Their whole world consisted of those few blocks.

"I was too anxious. I wanted it too bad ... It just wasn't me."

- Rose, on his first comeback.

Last month Reggie drove over to Raster and found the old basketball court gone. All that's left are the fading white lines. A few blocks away, Murray Park offers not only rims but the rarest of sights in a rough neighborhood: nets. Out of respect for Rose, and for the hope of a life beyond 71st Street, the Gangster Disciples and local residents protect the court.

A block west of the park, at least nine Roses lived in the small house on Paulina Street that belonged to his grandmother. His mom, Brenda Rose, worked multiple jobs, and her three older sons took care of Derrick, taking turns cooking meals. Reggie especially tried to be the father his brother never had. In an interview after his son, Derrick Jr., was born, Derrick offered a rare glimpse into the hurt he still hides, saying he knew he'd be a great dad, as long as he did everything different from his own father. Reggie is asked whether Derrick's dad had ever reached out to his famous and wealthy son.

"No," he says, and he changes the subject.

Despite Brenda Rose's jobs, the family fell behind in the usual ways that poverty encircles and traps: an unpaid bill to Sears, a bankruptcy a few years later in 2002, when 14-year-old Derrick, the same age as Endia Martin, was realizing that his skill might be the miracle a family like his needed to start over. He chased it at the exclusion of everything else, and although he made it, he and his family still carry the marks of Englewood. In expensive restaurants, with foie gras and lobster on the menu, Derrick will order a grilled cheese, ignoring the raised eyebrows and laughs of his brothers and friends, because there was a time when the comfort of a grilled cheese was the finest thing he could imagine.

Future generations of the Rose family will never know the poverty that Derrick and his mom, Brenda Rose, lived through. Chris Sweda/Chicago Tribune/MCT/Getty Images

BRENDA ROSE NOW lives in a nice house on a quiet, leafy cul-de-sac in the Chicago suburbs. Not long ago, she rented a bouncy castle for her 60th birthday, bringing all the grandkids over and finding a gift in their laughter, knowing they'd never live the life she left behind. Reggie Rose drives a Bentley and an Escalade, and at Harold's Chicken Shack, waiting on the order, he buried himself in his phone, looking at studio apartments in the same Trump Tower where his brother lives in a sprawling penthouse. They have investments, a share in the famous Giordano's pizza chain, and generation-skipping trusts so Derrick's money changes the arc of his family long after he's gone.

Derrick got the Rolls-Royce he always fantasized about, the one he promised he'd sleep in the first night he brought it home. He won rookie of the year in 2009.

Sitting on the back of Bulls team flights, he'd share his past with teammate Luol Deng, then ask questions about Deng's family and life in war-torn Sudan. Deng says he was struck by Derrick's compassion, by his innate understanding of overcoming something. "He was really interested in the African culture," Deng says. "He asked a lot of questions. It sparked his curiosity. His mom was similar too. When she met my mom, she asked a lot of questions. The questions somebody asks tells you a lot about a person. I think he asked questions like that because he cares. He has a huge heart. He can be emotional about it."

Then, in 2011, Rose became the youngest MVP in league history.

During the news conference, after being introduced with a comparison to Magic, Bird and Jordan, he smoothly thanked everyone, until he got to his mom. She looked up at him, and tears ran down her cheeks.

At the podium, he struggled to speak.

"Um ... ," he said, because how do you tell a story so heavy it drags down nearly everyone who must carry it?

Her lip quivered, and his lip quivered.

"Brenda Rose," he said, and his voice cracked.

They had escaped, and all because of him.

"Those were hard days," he said, looking down at his mom. "My days shouldn't be hard. My days shouldn't be hard because I'm doing what I love doing. That's playing basketball."

Eleven months later, he tore his ACL.

"I think everyone knew that I tore my ACL. I didn't know, and they were just trying to hide it from me," Rose says of his experience in the ER after being carried off the court during the 2012 playoffs. Jonathan Daniel/Getty Images

REGGIE SAT COURTSIDE that night, behind the basket, and Derrick fell to the ground right in front of his seat, maybe 10 feet away. All of the photos of the moment show the pain in Derrick's eyes, or the concerned doctors kneeling around him, but in a few of them, Reggie is visible in the background, sitting behind a TNT cameraman. He looks as if he's about to puke.

Trainers loaded Derrick into an ambulance. He'd left his phone in the United Center locker room, so he had nothing to do but think. The sirens stayed off, and in the back, still in his Bulls uniform, he thought he'd be OK. The ambulance hitting its brakes jostled his knee.

"Mine stopped at every light," he says now, laughing. "I felt a jerk at every light." His family followed behind the ambulance, a caravan of seven or so cars sticking close, but he couldn't see them. He was alone. Rush University Medical Center is a mile from the arena, rising between Damen and Ashland avenues, the boundaries of his former life, and inside doctors and nurses moved around, talking quietly to each other, running an X-ray and waiting for the results. "By that time," he says, "I think everyone knew that I tore my ACL. I didn't know, and they were just trying to hide it from me."

In front of the television, John Calipari watched the injury and knew the road ahead. He had reason to worry because, of the many things he'd learned about his former star guard at Memphis, one was Derrick's low tolerance for pain. One memory stuck out for the coach. Shortly after Derrick started practicing as a freshman, the Tigers scrimmaged against Saint Louis University, and going hard to the rim, Rose was forced to the ground by contact.

"He yelled like he was shot by a sniper," Calipari says, still remembering the stretcher. "I was literally physically ill."

He pauses, a savvy storyteller, waiting to deliver the most important detail.

"He practiced the next day," Calipari says.

At Rush hospital, Rose waited for his family to find him in his room. When Reggie finally walked through the door, he saw his brother still wearing his uniform, an air cast on his leg. "He's just looking at me like -- almost to the point that, like, he let somebody down," Reggie says. "He's like, 'I can't believe this,' with his head down. You know, I'm the strong brother. I'm the one that ruled with the iron fist. I couldn't protect him from that. And I couldn't protect myself from shedding a tear."

After about two hours, they gathered in Derrick's high-rise. He took off his uniform -- leaving one part of his life behind and starting another -- and stood in a hot shower. His family gathered in the apartment, and that night he could hear the murmur of their conversations. He climbed into bed and tried to sleep, unable to move his leg. Reggie tried to say the right things: "I said, 'Derrick, I know you a God-fearing man. It's like this: You prayed and asked God for everything you wanted in life, you went to college, you in the NBA, you got all this money. He gave you everything. So you gotta look at it like this: This could be a challenge for you. What do you have to do to keep it?'"

text

Peter Hapak

NEARLY THREE YEARS of recovery later, just three days before the first Bulls practice, Derrick Rose is finishing his grilled chicken at a hedonistic Rush Street steakhouse -- Gotta eat right, one of his many mantras -- and opening up about how the person sitting in this restaurant is very different from the one who went up in the air and landed in a heap: a physical change, yes, but an interior one too.

"You do look at everything," he says. "Start with yourself first. I looked at myself as far as just who I was as a person."

Rose approached his first recovery like a jock. He pushed himself. He believed, however foolishly, in the possibility of complete recovery, of resuming an ascent without losing anything. "I was too anxious," he says. "I wanted it too bad. I wanted to prove everybody wrong. I don't know, it just wasn't me."

He refused to come back until he felt ready, despite an avalanche of media and fan judgment. Something in his body seemed wrong, even when doctors told him his knee could withstand the rigors of a game. When he returned in the fall of 2013, he played 10 games before tearing the meniscus in his other knee.

The cruel, bad luck of it all must have called into question every deeply held belief about the world and how to navigate its obstacles. Some of this is supposition; he struggles to explain something he felt more than thought. While the first injury prompted worries about his body, the second seemed to prompt worries about the entire nature of things. Even the redemptive quality of hard work finally exposed itself as a shiny lie.

“He knows that he will never get back to that.”

- Reggie Rose, on his brother's former approach to the game

So with another season to watch instead of play, Derrick began studying opponents -- then he studied himself, seeing flaws he'd never noticed before. Winning a title required "breaking the code," as he puts it, so he vowed not to just fly around the court but to figure out what separated the champions. At home, Reggie noticed something subtle but important, which all children of doting mothers hungry for more time will recognize: "Tell my mother no," Derrick learned to say, creating boundaries with everyone, even the woman he wanted to give a new life to with his talents.

In October 2012, six months after his first injury, Derrick Jr. was born. As Rose recovered from his second injury, his son was becoming a little person. That changed Derrick too, perhaps most of all, making him imagine a distant future instead of the world right in front of his face. There's a funny story he likes to tell: Once, he stayed at the Four Seasons in Istanbul, a former Ottoman palace, cocooned in hushed luxury. Looking out at the water, he felt as if he had found the pinnacle of status, only to see an enormous yacht at anchor, more of a ship than a boat. After asking around, he learned that it belonged to the rock band U2, in town for a sold-out show. There is always something bigger to chase.

Turns out, his brother was right. The old Derrick Rose is gone. It's fair to wonder whether he's lost some essential part of himself in the transaction: Will he long for parts of the life he left behind? Rose already gets nostalgic remembering the chicken fingers from Rainbow Submarine on 71st Street, a place that's no longer safe for him to visit. What if he forgets about the way a hot grilled cheese felt when he first lifted it from the plate? Once the blinkers come off, they can never go back on again. The new Rose seems to be learning, a little more every day, that he's pushed by deeper desires than buying his mom a new house.

"My whole life was basketball and just trying to make it out of the area I grew up in," he says. "Of course, school was great, but my biggest goal was to make it out, and you had to go to school. I knew that at the end of the day, I knew I had to do something for my family. I was just thinking about my mom, and just trying to change her life. I knew that I didn't want to go selling drugs or cracking cars. I didn't wanna do that."

Sitting at the steakhouse, thinking about how his life has changed, he reveals his latest hobby.

"Reading," he says, shaking his head.

He sheepishly admits that he's started a lot of books but hasn't finished one yet. He's searching. "Even before he got hurt," Calipari says, "he was still trying to figure out: Who am I?"

One of the books Derrick likes is Malcolm Gladwell's Outliers, which explores the traits that make certain people successful. It's a book about Bill Gates, J. Robert Oppenheimer and the Beatles, but it's also a book about Derrick Rose. Leaving Englewood wasn't enough. He wants to win championships. He wants to be the greatest player in the world, then the greatest player ever, which means he needs to be somehow even better than before. Deep inside, he believes that these goals are possible, and that his talent can deliver them.

Newly curious, he seems happy. Everything he wants is right in front of him, and he'll know in a year, maybe two, whether he can have it -- or whether his dreams evaporated when he blew out his knee. All this will be fascinating to watch. His second mission begins now, and, as with the first one, he doesn't know how it will end. Internal drives aren't easy to understand, much less defeat, even if he is healthy; Michael Jordan won every battle he fought, and he is entering middle age unhappy and lost. Derrick Rose escaped his neighborhood and his old life, but he remains a citizen of his own ambition.

At 26 years old, Rose knows that every dunk comes at a cost. Evrim Aydin/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

HIS FIRST TIME on the court against real competition came at the Team USA camp in Las Vegas this summer. He talked about "making the team," like a junior high player, the language of someone starting over, and nobody knew what to expect. Reggie sat in the stands during the first scrimmage of the first day and described what happened: When the opposing point guard caught the first inbounds pass, he wheeled around and found the 2011 NBA MVP in an aggressive crouch, shuffling his feet, Derrick Rose guarding the full 94 feet.

A buzz started in the gym. Glances, then whispers, spreading the word: D-Rose is playing a tryout like it's Game 7.

"I'm in the stands," Reggie says, "I'm looking at everybody almost like, 'Yeah, motherf---ers.'"

Calipari watched the workouts in Vegas and saw the familiar explosiveness and quickness. The only part of Derrick's game lagging behind, he says, is the belief that everything will be OK once he steps onto the court. "I'm anxious," Calipari says. "He's still trying to figure out what his body's saying."

Nobody knows whether Derrick Rose will be the same, not even him, but he's ready to find out. Sitting at the steakhouse, which happens to be the one where Jordan once held court after home games, Rose is asked to visualize opening night in New York. He doesn't describe putting his jersey back on or the sound of the crowd or the glow of the lights. He's over the superficial, focusing on the process: Returning to the hotel from shootaround and, instead of wasting time in his room at the New York Four Seasons, goofing off on the Internet, he can see himself lying in bed, his legs wrapped in sleeves connected to the NormaTec compression machine, promoting circulation and positive blood flow. He imagines napping, resting his legs, then waking up and going to the arena. When he visualizes his return, he doesn't see himself playing. He sees himself doing work.

THAT TRIP TO the Hamptons gave him a final moment of stillness before the work began, and even there the coming struggle crept in.

"My mind, I'm always thinking," he says. "That's one of the reasons I'm so quiet. Just try to think everything through, process everything, realize where I'm at in my life. Realize some of the things I didn't achieve that I wanted to achieve. And just try to learn from my mistakes. And learn from other people's mistakes. That's why I been watching a lot of history -- learning about history and watching a lot of documentaries."

In Sag Harbor, Rose and his girlfriend rode bikes around town. They played hour after hour of Rummikub, a game they found in the secluded house they rented. Every day, they tried a different restaurant she'd researched and chosen, a mix of high-concept new American cuisine and linen-draped, waterfront-sunset perches. In the mornings, they went to a fancy resort-town breakfast spot. A man could not get further from the streets of Englewood, with endless new dishes to taste, from crab and eggs to organic red quinoa. The chef grows all the vegetables in a garden outside. Derrick tried the famous pancakes, with the boutique maple syrup, but one morning, he wanted something not on the menu.

He ordered a grilled cheese.

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com.

Follow The Mag on Twitter (@ESPNmag) and like us on Facebook.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader

Join the conversation about "The Third Coming Of Derrick Rose."