The Losses of Dan Gable

Wrestling's most famous winner is taking on one final battle: To save his sport and all he's ever been.

Feb. 12, Iowa City, Iowa

On the morning the IOC announced it would drop wrestling from the Olympics, Dan Gable was a continent away, fast asleep. It was dark outside. His wife, Kathy, sat at the computer, waiting on the coffeemaker to start. She scrolled through the Iowa wrestling message boards, and one thread caught her attention. When she finished reading, she hurried to the bedroom. Dan was on the left side of the bed, on his stomach. That sticks in her mind, for some reason -- him peaceful, unaware. She tapped him, asked if he knew anything about the Olympics getting rid of wrestling in 2020. He mumbled something and kept sleeping, for a few moments, until the information traveled through his subconscious and he rushed to the computer. The news rearranged his world. Sitting by himself in the dark, Gable struggled not to cry. He called the head of USA Wrestling and blurted, "Tell me it isn't true!"

Gable's phone started to ring. One by one, his four daughters called. They said they loved him and that he could save wrestling. His oldest, Jenni, called from her home up the road and described the look on her son's face when she told him. He's 9. An unspoken dream seemed to die in his eyes. This hurt Dan most of all. As the sun rose, he pushed away his pain to do the thing he did best: fight.

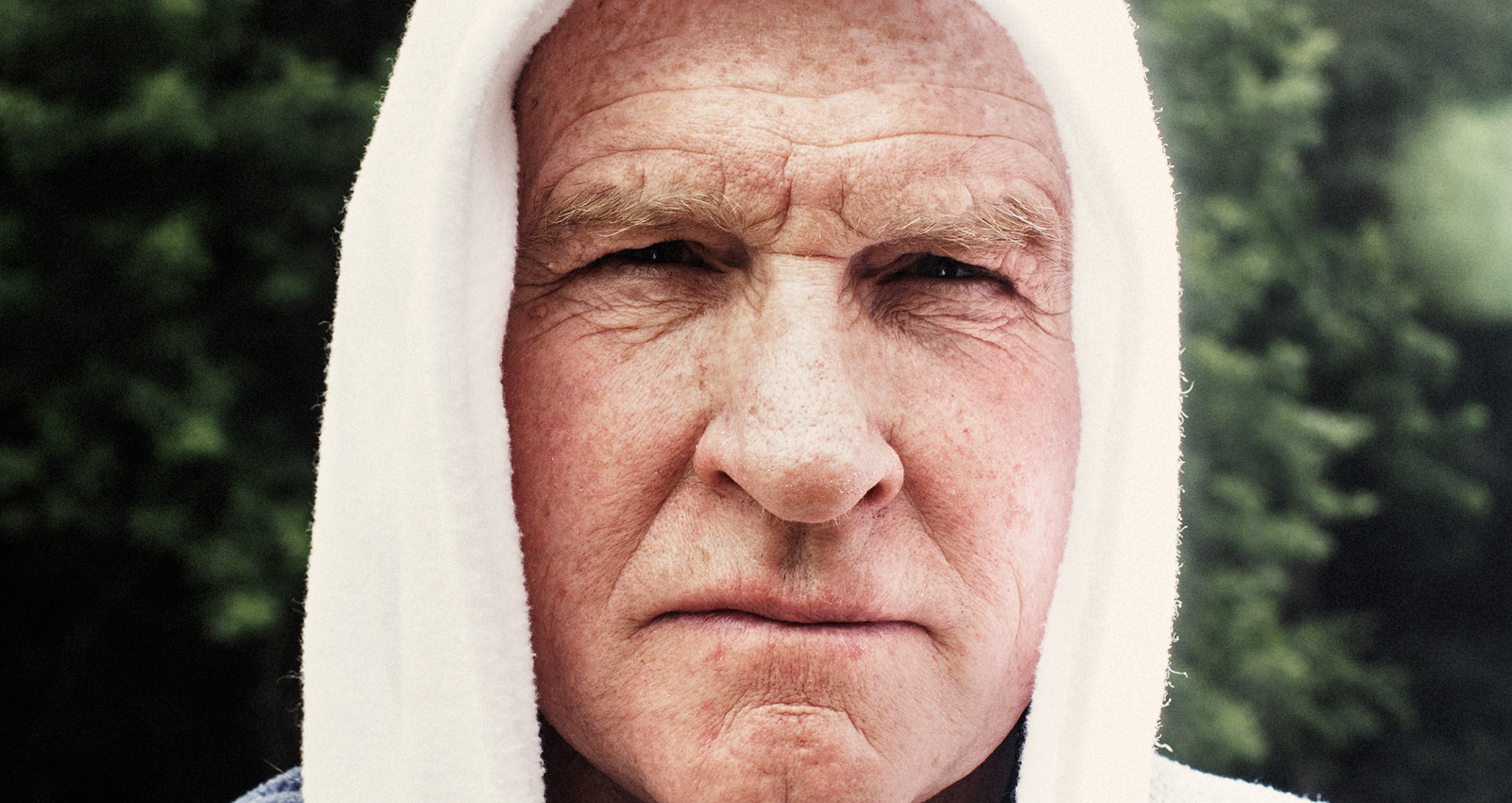

DAN GABLE PACES suite No. 8 at Wells Fargo Arena in Des Moines, trying to decide whether he can watch the last Iowa match of the NCAA wrestling tournament. It's March. The Hawkeyes, whom he hasn't coached in 16 years, are having a miserable weekend, with no national champions. Just the other morning, a former Iowa wrestler saw Gable punishing an unsuspecting elliptical machine in the hotel gym. When the machine had asked his age, Gable, who is 64, typed in 29, as always, and began attacking the pedals, grinding out frustrations about the IOC and the collapsing Hawkeyes.

"How you been?" the wrestler asked.

"I've been better," Gable said.

Now, in the last hour of the tournament, a scowl anchors his face. His eyes jump from side to side, scanning the mats. The arena sound system pours out decibels, sludgy bass lines and screaming guitars. Derek St. John, the Iowa 157 and last hope to salvage a national title from a tournament gone wrong, crouches at the center of the mat. Gable pumps his feet and looks like he might get sick.

"I don't think I can sit here," he says, stepping out of the suite into the hallway.

His life has been one of victory: He went 64 - 0 as a high school wrestler, 118 - 1 in college, won an Olympic gold medal in Munich without surrendering a point, won 15 national titles in 21 seasons as the Iowa coach. Outside in the concourse, feeling weak, then feeling guilty about feeling weak, he knows what must be done. Gable triumphs again -- over himself. He swings open the door and steps back inside. "I'm gonna watch," he declares, then almost to himself adds, "I can't be such a chickenshit."

St. John pushes his opponent into the mat. "Ride him like a dog!" Gable yells. The first two periods pass. Sometimes Gable just mouths words, intense, forgetting to speak. St. John is tied with 48 seconds left. The Penn State fans in the next suite are peeking over at the red-faced, bald man losing his shit. At rest, Gable looks like a retired math teacher, but under the influence of anger and adrenaline, he transforms. His eyes seem to shift from a soft hazel to a dull black, the color of an alien, subterranean element. Given the right stimuli, like a vital Iowa match, he seems a good sweat from his final wrestling weight of 149. The eruption arrives. Watching Gable melt down is like watching Picasso paint. He shakes and strains, a rocket on the pad. The flying spit and sudden fits of decorum, like "Jiminy Christmas!" -- Tourette's in reverse -- are followed by growling, intense curses.

"SONOFABITCH!" he roars down into the fulcrum of noise.

St. John bucks and twists, and with 38 seconds left, he breaks his opponent's grip and takes a 3-2 lead. He is going to win the national championship. Someone says, "This match is over," which pushes Gable to the edge. "No, it ain't!" he yells, his voice sounding like a gut-shot deer looks, ragged from days of this. "It's not over!"

"Four ... three ... two ... one," a friend counts down, and the horn sounds. Everyone in the Gable suite celebrates, except Gable himself, who is almost panting, his eyes glassy. Without anyone noticing, he slips out the door into the concourse. Leaning over, with his head down, the tears come. Soon he is sobbing, his back to the suite. His shoulders heave up and down, shaking. A former Iowa wrestler stops to swap war stories, then suddenly backs up, a look of horror on his face. Mackie Gable, Dan's youngest daughter, steps outside and finds her father weeping.

"I've never seen him like that ever," she says.

Gable doesn't say anything. What would he say? Not even he really knows what's happening to him. Mackie seems unsure, taking a step toward him, then a step back. She doesn't know what to do. She ducks into the suite, scans the room and calls, "Mom?" Kathy Gable comforts Dan, talking softly to him, and soon he returns, drying his eyes, trying to explain something he doesn't understand.

ESPN The Magazine

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Sept. 2 NFL Preview issue. SUBSCRIBE»

Later that night, some friends sit around the hotel bar, just as baffled as Mackie. Why was the hardest dude on the planet crying because a wrestler he doesn't coach won a match? Most of the guys at the table are young, and they see Gable as superhuman. But an old friend, Mike Doughty, has known Gable for decades.

"Every once in a while," he tells them, "I'll be traveling with Dan and things like that will hit. He has these things locked in trapdoors and eeeek ..." -- he makes the creaking sound of an old hinge opening -- " ... they start coming out."

Gable works out in his home gym, needing to do his daily work before he rewards himself with a Mountain Dew. Andrew Cutraro

1955, Waterloo, Iowa

People think Dan Gable isn't afraid of anything, but that's not true. He is deeply afraid of one thing. Hidden in his past, before he ever wrestled a match, there's a story most people don't know. Even his four daughters have never heard it. When he was a small boy, his parents drank, and they fought. The Gables always seemed to be one bad night from breaking apart, leaving Dan without a family: alone. So when Mack and Katie went out on the town, young Dan would make his way to the front of the house. He would station himself in the big picture window, scared that they'd come home and get divorced, or maybe not come home at all. From time to time, he'd suck his thumb. All night, he'd peer down the street, looking for headlights.

BACK HOME, HE's got a 45-acre spread he's put together in pieces over the years, a place to live out his uneasy retirement. This is where he was before the wrestling tournament, and where he would return when it ended. Today, a month after the IOC decision, he sinks down into his hot tub, which overlooks a wide yard of snow, downrange from the two cement deer that, on occasion, real deer like to hump. Gable thinks this is hilarious. He's soaking after his intense daily workout. There's a sign above his head that says: Whatever Happens In The Hot Tub Stays In The Hot Tub.

Gable sighs, a look of mock resignation on his face. "Nothing's ever happened in the hot tub," he says.

It's late afternoon at the compound, near sunset. The buildings -- the main house, his clubhouse with a sauna and gym, the barn with his axes and Everlast heavy bag -- look like they belong in a Nordic postcard, all dark wood and peaked rooflines. He jokes that the set of "Rocky" was stolen from him.

He's focused on overturning the IOC decision. When the news broke, Gable invited a reporter to his home outside Iowa City and to the NCAA wrestling tournament, which remains a holy week in his family. He's still the most famous person in the world of wrestling. A Des Moines newspaper reporter once wore an Iowa hat to a Russian village during the Cold War, in the mountains near the Siberian border, where an American had never been. A young man stepped out of the crowd, pointed toward the hat and said one of the few English words he knew: "Gable."

He sinks down farther into the water. The heat helps him think. He's been doing a lot of that lately, out here by himself, looking back at a life of competition and pain.

Steam rises off the water.

"I never wore a mouthpiece," he says suddenly.

He sticks out his tongue. Gouges and divots cover the bottom, like a target-practice soda can, deep scars and even holes, dozens of them. Wearing a mouthpiece would have prevented the holes and the mouthfuls of blood he swallowed and spit out, but it would also have made him weak, made his jaw slide, made him feel vulnerable. He welcomed the hurt. Now he clenches his teeth. He's always punished weakness with suffering, putting on a war mask for the world and for himself. His face hardens, his mouth curving into a frown, his muscles firing, looking like a weapon.

"It makes you strong!" he roars.

Gable leaps from the hot tub and dives into the drift of snow.

"Ahhhhhhhh," he moans, a cloud of vapor exploding as bare skin hits cold ground, moving his arms and legs back and forth, carving out wedges. Gable is spread-eagled in his backyard making goddamn snow angels. Just as quickly he jumps back into the hot water, his body temperature skyrocketing, the snow melting off.

"It burns," he says, gritting his teeth, and he sounds supremely happy.

HIS JOURNEY HAS consumed all of their lives.

For years, if you saw Gable at a wrestling event, you saw his wife, Kathy, and his four little girls. At Carver-Hawkeye, they sat in section NN, seats 1-6, the first two rows. If you've seen him at a match lately, they're still there, grown up, screaming down at poorly performing wrestlers, questioning their manhood, urging a coach to "slap the shit" out of one who celebrates a poorly wrestled match. Forget winning an Olympic medal. Are you man enough to marry a Gable? His daughters are funny, pretty and intense. All ended up with former athletes, and only Molly lives outside the state of Iowa. Jenni and Annie both live in Iowa City. Mackie's just up the road in Dubuque, and they get together as much as they can, mostly around wrestling events. During a speech not long ago, Gable laughed about the rolling circus that travels with him. "My wrestling and family go together," he said. "It's always been that way, from day one with my mom and dad, my sister, my wife, four daughters, grandsons, son-in-laws. They're all here." Some coaches ignore their families on their climb to the top; Gable needed his to be with him, as Sherpas, eventually as fellow climbers. His career molded his family, then welded it together. Wrestling kept his daughters from sitting in a window looking for headlights.

Kathy Gable knew he needed to build his family around wrestling. A blue-eyed Iowa girl, hilarious but fierce in defending her family, she found a soul mate in Dan. She lived with the storm of his career because she loved his willingness to devote himself fully to something. Even now, she alone seems capable of seeing through the shell into the real Dan Gable. He turns to her for the simplest of questions, such as: "When did my mother die?" They first met at a party. She lived in Waterloo then, in high school, and Dan, at Iowa State, sometimes trained in his hometown. For their first date, two years later, he invited her on a bike ride. Between that ride and their wedding some 12 months later, in 1974, he called her every night. The calls came from his desk at the Iowa wrestling office, after he'd finished coaching.

The Gables measured time in seasons, their world growing as small and insular as Dan's. Until high school, or maybe even college, Mackie thought the John Lennon song "Imagine" was written especially for a 1992 wrestling highlight video. She thought it was about wrestling, she admits, sheepishly. Dan's obsession became theirs. Even though he chose this life and they did not, that distinction became smaller and smaller until it ceased to matter at all. "He brought his work home with him a lot," Mackie says. "His life was his wrestling. When my dad was coaching, there would be some nights at home when it was scary."

He threw a mug through the Christmas tree. One night they heard a loud crash; Kathy had asked Dan why he wouldn't kick a wrestler named Rico Chiapparelli off the team if he was causing so many problems, and Gable flipped over the kitchen table. The girls' bedroom doors had holes in them; they'd slam and lock them, and Dan would punch through them. Boyfriends getting the tour would see the holes and make a mental note. The girls never actually felt in danger, just that they needed to stay clear. Before a match with main rival Oklahoma State, the girls knew not to talk to their dad, and if they saw him in the tunnel, not to expect a hello. They all shared the cost of his obsession.

Then, in 1997, burned out and with chronic pain in his hip, he quit.

Without wrestling, he felt something missing. So did his family. Mackie cried during the final news conference. Even though she says their relationship improved after he quit, since he suddenly had time to watch her play soccer, she also wanted him to keep coaching. It's hard to explain, this dichotomy, but when he gave up that job, they all lost something.

"I still don't think I have forgiven him," she says.

They needed the clarity of Gable's obsession. Without it, they were a different family. Mackie was in elementary school when he quit. She wanted to wrestle in junior high school, but her mom wouldn't let her join the boys team. Instead, she volunteered to be the high school wrestling manager, staying after practice to clean the mats. Her reasons are her own, but it's hard not to see a girl trying to keep a world intact. They followed him on his journey and counted his successes as their own. "Our gold medal," Mackie starts to say one day, laughing, correcting herself. "My dad's gold medal hangs above the fireplace. It's been there our whole life. It's almost like something we've looked up to."

During the holidays, Gable sits in front of his television and watches "White Christmas." He's seen it hundreds of times, sometimes alone, sometimes with his kids piled around. It's about Gen. Waverly, who is relieved of his command and struggles to build a new life. At the end, Gen. Waverly puts on his old uniform and is greeted by the soldiers who loved him during the war, who sing "The Old Man." This is the Gable family's favorite part, because it echoes their own lives: a general and his troops, happy to be finished with the battle but missing the fight. At the end, Dan always falls silent, tears in his eyes, no longer thinking about an old movie but about his wife and his girls.

"We'll follow the old man wherever he wants to go," the song goes. "Because we love him."

The centers of the Gable home are the Olympics and the memory of his sister, Diane. Andrew Cutraro

GABLE SPENDS HIS days trying to be useful. There's a wrestling-size hole in his life, and he is always trying to fill it. His struggle is never clearer than when he stops by the Iowa wrestling office, to pick up mail that still arrives there addressed to him, or to sign autographs. One afternoon, Gable comes into the reception area, making small talk. He asks the secretary, "You need me?"

She smiles and pulls out a stack of posters for him to sign.

"Don't I always need you, Dan?"

"I hope so," he says.

She gives directions, telling him to just sign his name, or to add a personal note to a specific fan. After finishing, he walks up a narrow stairwell, toward the lobby of Carver-Hawkeye Arena. People nod when he passes, and he zips his Iowa wrestling coat. It's freezing outside. A bitter laugh escapes his lips, and he looks tired and uncertain.

"I don't know where I'm at when it comes to this Olympic wrestling," he says. "I almost feel -- not useless, but ..."

The IOC's decision is based on internal politics, he explains. The international wrestling governing body's leader and lieutenants weren't respected in the Olympic community and were told repeatedly to make changes to the sport, to fix many of the confusing rules that had been added over the years. They refused. After the IOC decision -- its ruling can be cemented or reversed in a September meeting, during which wrestling, squash or baseball and softball will be chosen -- the president of FILA, the international wrestling body, was pushed out by his own board. Gable has used his fame to bring awareness, and to lobby behind the scenes, constantly working the phones or getting on planes. He's on fire these days, energized. Gable is on the newly formed Committee for the Preservation of Olympic Wrestling. Dan calls it "C'Pow," like the sound a fist makes on someone's jaw. This battle has, as Kathy Gable says, awakened a sleeping giant. He is fully himself again, filling up the leather calendar he takes everywhere. "Dan is a man of purpose," his friend Doughty says. "This is a new purpose."

Part of his role with CPOW is helping redesign the rules, an important request from the IOC. But Gable fears that the old FILA politics will keep the rules from changing. He fears he is powerless to create that change.

"I don't know," he says now. "I'd like a little more ability to have my fingers on it."

Outside Carver-Hawkeye, he takes small, sliding steps toward his truck, past the statue of him put up a year ago. The bronze Gable isn't lifting his fists in victory, or wagging a finger, but raising his arms in what wrestling fans recognize as a stalling call. It's as if the statue of Lombardi outside Lambeau Field were forever calling delay of game, demanding his teams keep pressing. It's perfect, really. There was no greater sin for a Gable wrestler than to be caught stalling -- backing up, eating clock, not attacking and destroying -- and once Gable even screamed at a ref to call it on his own guy. The statue is addressing everyone who passes, demanding that they keep fighting. Even before the IOC decision, Gable worried about the future of his sport and hoped to inspire people to save it. On the plaque, he wanted the inscription to say STALLING, as if the bronze Gable were screaming at people. School administrators worried people wouldn't get it, so after weeks of fighting, they settled on a compromise: (NO) STALLING. The statue is also there for his girls and for his grandchildren, so that if they ever need advice when he's dead and gone -- he figures he's got 15 years -- there will be a piece of him left, forever, reminding them to get off their asses and fight.

A student walks past and doesn't recognize him. Gable looks up at himself, and down at the plaque, which is covered in snow, his carefully chosen message obscured. His face is chapped from the cold. Leaning over, he carefully wipes the snow off with his hand.

The Gable statue outside Carver-Hawkeye Arena calls "stalling" on those who pass by. Andrew Cutraro

THE FIVE-MILE drive from the arena back to Gable's house takes him from the heart of campus into gentle rural hills with clapboard farmhouses and grain silos. It's just him and Kathy now. All four girls have moved out, started lives of their own. In five years, he'll have been retired for as long as he was a head coach.

It's a Sunday afternoon, and he heads down to the basement, which is covered with trinkets from his travels. He loves the two cats, which like to crawl on his legs. Rudy is outside, playing in the woods, but Peekers is by the couch, hacking and dry heaving. The noise stops Gable and he looks down, his face stern.

"Don't puke," he orders.

The cat hacks a few more times, bobbing her head, then vomits all over the carpet. Dan takes a step back, then rushes toward the door.

"Oh, she puked," he says. "Oh god."

He looks up the stairs.

"Kathy!

"Kathy!

"Hey Kath!"

"What?" she calls.

"Kath! She just puked. It wasn't good puke either."

In the kitchen, Kathy starts laughing, imagining the scene.

"It looks gray," he says.

He is helpless in the face of the sick cat. Fierce showdowns with Peekers seem like a comical use of the authority he built by demanding everything from himself and from athletes who wanted to be like him. Even 16 years after losing the opiate of competition, he's still grasping for something to replace it. One of his girls says he lost confidence in himself when he turned over the program he built, too burned out to continue, his identity too tied to wrestling to ever let it go. "I've had some unbelievable conversations with Kathy Gable that Dan Gable doesn't know about in that f---ing closet right there," says current Iowa coach Tom Brands, sitting in the Iowa wrestling room. He later elaborates: "She just ... it just pains her that he's not content. He needs something to do. He needs to be relevant."

That's why Gable never fully pulled away, even after he left coaching in 1997, making good money on the lecture circuit, keeping an administrative job in the athletic department. From the beginning, he worked to stop the death of wrestling, many programs cut because Title IX required that schools add women's sports, and the scholarship-hogging football teams paid everyone's bills and were untouchable. The fight gave him focus. When asked by Al Gore to appear with him at an Iowa rally, Gable had a single question for the vice president: What is your position on Title IX? (He did not appear at the rally.)

When Gable started lobbying, colleges were losing more wrestling programs each year, down from 146 in 1981-82 to 77 in 2011-12. His work paid off. After years of a slow reduction in the annual losses, the number of D-1 programs held steady last season. Every state but one now has high school wrestling, and every state but three has college wrestling. "Saving the sport" became his mantra. Still, most afternoons he found himself drawn to the Iowa wrestling practices, sitting in the bleachers like a fan, offering tips. Year after year, when the room cleared, Gable would change into his gear -- he kept locker No. 1 -- and practice moves on the Takedown Machine, trying to keep intact a world he'd first built as a seventh-grade boy.

His time in the wrestling room, and his quest to make sure the sport survived, helped control the storms he felt inside. Gable's life is governed by justification and guilt, as if he's forever paying off some unseen debt. He doesn't like to eat, for instance, without working out, constantly balancing a ledger in his mind. One day in March, he stared at a bowl of pasta, hungry and stubbornly trying not to eat. He'd skipped the gym and now looked longingly at the noodles.

"I don't deserve it," he said quietly.

May 31, 1964, Waterloo, Iowa

Dan and his parents went to Harpers Ferry, Iowa, on the Mississippi River, to fish. They left his older sister, Diane, at home. She was 19. That night, a local boy raped her and stabbed her to death with one of the Gables' kitchen knives. A neighbor found the body. The family threw away all its knives, not knowing which one had been used. Dan's parents fought, torn apart by the murder. They wanted to sell the house and move, but Dan begged them to stay. Nobody touched Diane's room. Her ghost lived there. At night, Dan heard the fights, the words burrowing into his memory, where they'd remain forever. The drinking escalated. He'd lost his sister, and now his deepest fear was coming true. The family was dying with her, and he would be left alone. One evening, his mother screamed, "I wish I'd raised her a whore!" and that was all Dan could stand. Enough! he thought. He got out of his bed, crossed the hall and climbed into Diane's bed, turning to face the wall. Half an hour later, his parents opened the door, humbled by the courage of their son. He felt the bar of light shining on the bed but stayed still. That night, he didn't sleep a wink. In the morning, he moved his things into Diane's room. The arguments slowed, then stopped, and his parents focused their attention on Dan, who started his junior wrestling season on a tear. He never lost, and his parents never missed a match. Dan loved the look on their faces when he won. He wrestled with a fury his opponents did not understand.

DIANE REMAINS A daily presence in the Gable home.

Around the corner from Dan's favorite chair, an overstuffed brown recliner, is the big family room. Above the fireplace is Dan's medal. Kathy has already put out Easter decorations, including stuffed bunnies and an Easter tree. But the first thing you see when you walk in, in a prominent place by the door, is an 8-by-10 picture of Diane, smiling and happy, forever a teenager.

"That's my sister," he says.

He's always been a protective parent, never letting his girls stay home alone overnight, even when they were in college, no matter how much they complained. He put hammers in their cars in case they ran off the road into a body of water. Diane's death is a psychic phantom limb, a complicated pain he talks about more each year, even if he still can't articulate how it makes him feel. One afternoon, he shows his collection of oversize black scrapbooks, which live in the same room as his used crutches and a pile of rifles and shotguns.

His mother made the books, collecting mementos from his journey, starting with local papers, rising up to Sports Illustrated profiles. Katie and Mack Gable kept everything. His parents saved his weights from high school, which he still uses in the barn. When his mom died in 1994, he found hundreds of letters he'd written in college. The Gables invested so much in their only remaining child that everything touched by Dan took on a talismanic meaning. Later, over beers at a local bar, he tries to remember when the collecting began.

"They were doing it before I died," he says, then catches himself.

He's quiet for a moment.

"Before my sister died," he says, and he changes the subject.

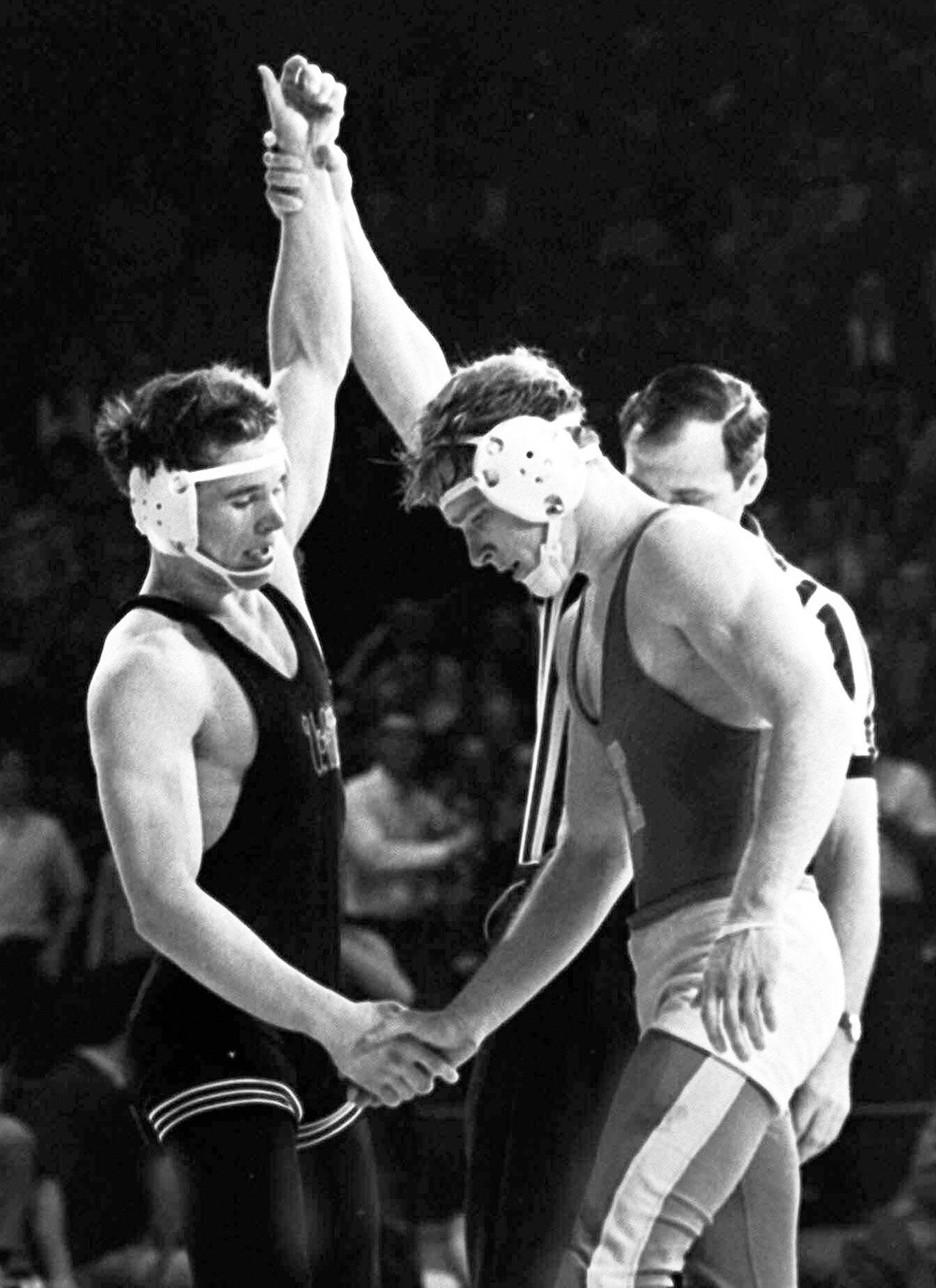

March 28, 1970, Evanston, Illinois

After moving into Diane's room, Gable kept winning. He graduated from high school 64-0, a three-time state champion. He didn't lose as a sophomore at Iowa State, or as a junior. He won 118 times in college, entering his final match undefeated. An unknown opponent from Washington named Larry Owings waited. ABC's Wide World of Sports showed up. Gable lost. The pain of his sister's death had been waiting on a moment of weakness, an opening, and in defeat, he couldn't find the strength that had gotten his family through her passing. He thought he'd let Diane down. He'd let his mom and dad down. When he got home, he avoided his parents. When his mom would get him on the phone, he couldn't talk. His throat closed, and the words refused to come out. Everything unraveled. Katie Gable drove to Ames. She confronted her son and slapped him, hard. Dan turned his focus to the Olympics. He got better, more dangerous. Every day for two years, he tortured himself, refusing surgery for torn cartilage in his knee, scared he would miss out on the Olympics. All else he shoved aside, or pushed back down. Nobody scored on him in Munich, and when he won, he tossed the medal in the bottom of his gym bag. For a brief period, his panicked parents thought it was lost. They didn't understand. For him, the reward wasn't a medal but seeing how winning it made them feel. A family was his reward. Years later, sitting in a Des Moines hotel hot tub, Gable would bring up the Owings loss, which he does about once a day. He tried to describe what it did to him, and to his mom and dad. Finally, choosing his words carefully, he said, "It was like a death in the family."

Moments after his only wrestling defeat in college, Gable congratulates Larry Owings, the man who beat him. AP Images

WHEN THE GABLES finally arrive in Des Moines for the NCAA tournament, 37 days have passed since the IOC decision. "I'm coming here with one thing in mind," Dan says after checking into his suite on the 10th floor of the Savery Hotel, reaching into the closet and thumbing past two Iowa jackets before pulling out one that says USA. In the days ahead, he'll talk to the Iowa state legislature, to groups of fans, to dozens of reporters, using his fame and influence to protect Olympic wrestling. Everyone expects him to lead the fight against the IOC. All his life, Gable has been able to sense other people's hopes, just as he feels other people's pain as if it were his own.

Taking on other people's pain is why he left the sport. The Des Moines Register's wrestling beat writer, Andy Hamilton, said that Gable quit coaching, in large part, because he could no longer stomach seeing wrestlers he cared about lose. It sounds like coachspeak and only makes sense once you've watched Gable watch wrestling. In Des Moines, as the tournament gets under way, he starts making noises that sound like an animal's death rattle, a moan that starts somewhere very deep inside.

"Why do I do this to myself?" he says.

He sets his feet far apart and leans down toward the mat. His hands twitch. The Hawkeyes lose match after match. They're not wrestling aggressively, not attacking until the end of the third period, and after yet another defeat, Annie rushes back to Dan and says, "Dad, you gotta start coaching again," an idea that is repeated not much later by a former college wrestler in the suite. "You want me to be dead in about two years?" Gable says. "I got out of it to save my life."

All of his angst coalesces into one brief window of agony, on Day 2, during Matt McDonough's quarterfinal match. A year ago, McDonough dominated people, and now, for some reason, he is wrestling without anger or energy. Upset at the Big Ten tournament, he'd thrown his second-place medal in a trash can and stormed off. Now he is losing again.

"Dad coached McDonough's dad," one of the girls explains.

Generations now have come and gone, and Gable remembers the losers more than the winners. He can rattle off the wrestlers who suffered with him but never got the brief redemption of a championship. He never cheered after one of his own matches, but he'd leap into the air after theirs, and he'd mourn with them after defeats, and sit in a sauna wearing a coat and tie to help them make weight. He lived and died with his wrestlers. One of them, Chad Zaputil, still haunts him. Zaputil wrestled at 118 and lost three times in the national finals. After the first defeat, he got the Herky the Hawk mascot tattooed on his thigh. After the second, he got another tattoo, over his heart: an angry golden hawk, wings out, talons sharp and ready. Then he got beat a third time, ending his career. Zaputil disappeared. Gable heard the whispers and searched for him, hanging at his house until he saw him go inside. Gable knocked. Zaputil wouldn't answer, so Gable broke down the door.

"Let me see that tattoo," he demanded.

"No," Zaputil said.

Gable ripped Zaputil's shirt off, and what he saw staggered him. The tattoo had been expanded, to show the hawk clawing out a human heart, with blood splattered all down Zaputil's torso.

"It just killed me," Gable says. "I couldn't handle it."

He thought quitting would spare him the pain, but he was wrong. In Des Moines, McDonough is losing, and Dan is in a panic. His family panics with him. Mackie brings her knees up to cover her face, wraps her arms around her knees. Jenni screams. Dan is screaming now too, spittle flying out of his mouth.

"What's he doing?" he yells. "McDonough, get up! What's he doing!?

"McDONOUGH! GET OUT OF THERE! No, he ain't. No, he ain't. That's bullshit. Ohhhhhh. McDonough got beat! NICE JOB, McDONOUGH!"

The arena falls quiet.

"I'm gonna throw up," Mackie says.

Gable can't sleep that night, haunted by McDonough's loss and the losses of every wrestler he's seen in the past few days, even ones from other schools, kids he's never met. It all combines in his chest, a consuming ache.

"I know the pain," he says.

Gable is a devoted father and grandfather. Here, he's pictured with his four girls -- Molly, Jenni, Annie and Mackie -- all of whom are now married. Andrew Cutraro

HIS DAUGHTERS HAVE been watching. Not just the past month, or the previous few days, but their whole lives. They've seen the peaks of arrogance and valleys of self-doubt. They've learned a lot about him by having their own kids. If they don't fully understand what pushes him, they know which clues are important. Lately he's been taking the time to understand new things, like the straps and buckles on his grandkids' car seats. He's been more emotional, calling old wrestlers on the phone to tell stories about how it used to be.

These things must mean something. During a lull in the wrestling, the girls and their husbands sit in the suite, trying to connect the stories, explaining how losing the Olympics feels like the beginning of the end to Dan. "If they drop wrestling," son-in-law Danny Olszta says, "he'll feel he failed."

"I feel bad for my dad," Mackie says. "I don't even know how to explain it. This is ... his life. Having that taken away, I don't want to say it's killing him ... You gotta understand, wrestling is what he went to when he recovered from his sister passing away."

Oldest grandson Gable sits in his chair, never taking his eyes off the mats. His patience astounds them, and they're starting to wonder what his future might hold. He's 9, but he can lock into a sporting event for hours and is so disciplined, he cries if he thinks he might be late for school. While he watches, his mom and his aunts crowd around one another.

"I feel like none of us would be here were it not for wrestling," Jenni explains. "After what wrestling did for my dad and his family, after their tragedy. Wrestling saved them from going down a path of destruction."

Jenni thinks the IOC members would change their mind if they came to Iowa. Drive them through the cornfields to this suite in a deafening, packed arena. Meet her family. See what wrestling means out in the middle of the country and in places like it all over the world, where the thin line between survival and extinction is guarded by toughness. Make them understand what Olympic wrestling has meant to her family, to her father and to her sisters, and what it will mean if it is taken from her sons.

"I have these kids," Annie says. "I have this son. I have this new baby son. How can I possibly look at them and tell them they can never become an Olympic champion? It's part of their blood."

"Like their grandpa," Mackie says.

GABLE HAS BEEN watching himself too, looking inward, changing, thinking about his family. This year, for the first time since seventh grade, he hasn't spent at least three or four days a week in a wrestling room. One day, as he walks from the hotel to the arena, he tries to explain why. There's a long pause as he thinks.

"Time to move on," he says.

"Why?"

"I had never seen a sunset," he says, and he's laughing at himself, at how he sounds. The wrestling rooms of his life come back to him, bunkers, dark and hot, without windows or natural light, a lot like a poet's vision of hell. Dan loved them. The Iowa wrestling room was perfect, carefully constructed over decades as a confessional, a place where pain could be traded for absolution. Even when he went on long speaking trips, it remained there, a spiritual home. The idea of the room kept him tethered to something, and he remained its alpha. Then he stopped coming.

"This year," he says, "I was getting pulled in one direction toward the wrestling room, but ..." -- he sighs -- "... I think my wife, the love for my wife ..."

There's a yawn of silence. Ten seconds pass.

"I got hurt in July," he says.

He hesitates, considering how much to reveal. "Starting a chain saw," he says.

His rotator cuff, long abused, snapped. He felt it immediately, a burn, and when he says "burn," his voice changes, like he's feeling it anew. He couldn't use his arm for two weeks, couldn't crank a boat, couldn't chop wood. Then he reinjured the shoulder -- someone tapped him and he swung around, his own motion doing the damage -- and doctors told him he couldn't go into the wrestling room. During the heat of summer, when a team is formed, Gable stayed at home, not connected to the Hawkeyes. He liked his time alone, looking out on all he'd built. That surprised him.

The rotator cuff injuries, and an earlier painful fall while hauling in the Christmas tree, had left him hobbled, feeling his age, thinking about the future. He couldn't wrestle, not even on the Takedown Machine. Piece by piece, he'd been stripped of the things that had kept his demons in check since seventh grade, in the gray cinder block dungeon at West High School. First he lost his sister and his perfect record. Then he lost his wrestling career, then his coaching career, then he lost wrestling itself, seeing former opponents fall victim to Title IX and shrinking budgets. He lost his relevance. His girls grew up. He endured eight knee operations and four hip replacements in exchange for whatever relief wrestling brought. Then doctors told him he couldn't wrestle people any longer, and the Christmas tree and the chain saw nearly took away the Takedown Machine, and that is just about that. Some essential part of Gable is gone forever. He'll likely never wrestle again, stripped of the most important part of himself, his ability to keep his pain buried inside.

Now the IOC wants to take away the Olympics.

Gable walks four or five blocks during this conversation, winding above the sidewalks and streets of Des Moines on the skywalk. A guard checks his ticket and waves him into the suite level. Making the turn down the hall to join his family, he thinks about his useless gear gathering dust in the Iowa wrestling room.

"Maybe it's time to turn my locker in," he says. "It might be."

His words carry many different emotions: surprise, relief, resignation and, just maybe, acceptance.

"They might need it," he says. "I don't want to hold back any progress."

Gable loves sitting in the sauna, even traveling overseas once to an international sauna convention. Andrew Cutraro

A FEW HOURS before Iowa's final round of the tournament, Gable and two friends find a sauna in a private gym, accessible by an unmarked door and a metal staircase. The temperature rises toward 200. Gable scoops his hand into the water bucket to splash his face. He's been vulnerable, raw after the Olympics fight and the Hawkeyes' collapse. Maybe that's why it hits him now. The memory of his sister comes to him, vividly. He is being pulled backward, toward her death and his complicity in it.

He brings it up on his own, and the story trickles out. Every now and again, he splashes water on his face. His friends look at the floor in silence. The sauna is completely quiet except for Dan's voice, which sounds far away.

It was a Sunday.

They'd driven the block from a rented fishing cabin to a nearby pay phone. He sat in the backseat. Nobody answered at the house in Waterloo. Dan remembers his parents feeling antsy. They got a neighbor to go check. He said the door was locked but the television or radio was playing. Mack Gable told the guy to get in the house and call back.

They waited.

Dan remembers the noise the phone made, the metallic, guttural rattle.

"Rrrrrrring," he says now. "Rrrrrring."

It's hard to breathe in the sauna.

Mack answered and listened as the neighbor described Diane's half-naked body dead on the living room carpet, in the same room where Dan once sat in the window. Katie kept bumping her husband, asking over and over what he was hearing. She studied his face for clues. Mack dropped the phone. It swung back and forth, slowly, back and forth. Back and forth.

Dan sees the phone again. He pictures it now: a swaying receiver connected by a creaking metal cord to a box.

"She's been hurt," Mack said.

"How bad?" Katie asked.

"She's not alive," Mack said.

Dan hears the words again. She's not alive. The sweat rolls down his arms.

Katie tore off toward the cabin, with Dan sprinting after her, Mack chasing in the car. When Dan reached the cabin, he found his mother pounding her head on the floor, over and over again.

"Blood on the floor of the four-dollar-a-night cabin" is what he says in the sauna, and his friends don't say a word.

"It's hot," Gable says suddenly. "I'm gonna step outside."

Mike Duroe and Doughty watch him compose himself. Gable returns, ready to continue. His family had started the endless drive across small Iowa highways when Dan said he might know something. Mack swerved off the road, pulling his son from the car. Dan explained that a neighborhood boy named Tom Kyle had been saying aggressive, sexual things about Diane, but Dan thought it was just normal guy talk. He never said anything to anyone. He didn't know. He was just a boy. Mack slapped Dan, hard, across the face, then hugged him. Pain and relief, even then.

"Helped him," Dan says now. "Helped me."

They drove home, and Dan moved into her room, winning 162 straight matches before losing. Some part of Gable never stopped blaming himself for her death.

His story isn't finished.

Tom Kyle went to prison for life. Then two years ago, on the ride home from a fishing trip, Dan's cellphone rang. It was the prison. Kyle, they explained, was dead. Dan looked out his window as he listened and shuddered. He was passing the parking lot where they found out about Diane, where his dad dropped a pay phone that swung slowly on its cord. Kyle's death brought back the sorrow and grief, the anger and guilt, and Gable walked around his 45 acres when he got home, yelling and screaming at the tall pines. He needed to purge these feelings.

"I didn't get it all," he tells his friends, standing outside of the sauna, leaning in, "but I got a lot. Like the Owings loss."

He closes the door and sinks into a chair. Like the Owings loss. Something is very close to the surface, and he tries to force it back down. The pain about his sister is combining with all the other pain he's felt in his life, with Larry Owings, with the Olympics, even with McDonough. He struggles with it. This is the price of trying to bury a lifetime of hurt. At some point, each loss stopped being a separate thing, blurring into the ones that came before, until there isn't even such a thing as individual losses, just loss. Every new pain feels like all his pain. Gable is hunched over. His friends wait for him to move. He rises to his feet and raps the sauna door goodbye.

Four hours later, the emotions that started in the sauna force their way out, released by his joy over Derek St. John's national title. Mackie rushes to find Kathy, who comforts him. "I had to get it out of me," he says, still sniffling, wiping away his tears. "A lot of pain. I had to have a win, just to get it out of me."

THEY'RE BACK IN Iowa City. It took all morning to pack the hotel room and load grandkids into the proper vehicles. There'd been drama with Annie, who didn't want to stop and eat together on the way back. It turned into a big fight, tempers flaring, everyone sensitive and exhausted. It's an enormous pain for moms with young children to relocate to a different city every March for a wrestling tournament.

Dan walks through a foot of snow toward the barn, cranking the ATV, the powder blowing over the tires as he accelerates through a clearing in the woods. He pulls up to a small barn with a low ceiling and steps inside to gather wood. The logs are still wet, and the air smells like oak and elm. He's thinking about the recent drama, not sure if he'll be able to get everyone to do it again next year.

"I don't know how long we'll keep up this wrestling stuff," he says.

He steers the vehicle onto a hill where he used to run, pressing the pedal to the floor, kicking up a wake of snow. When he comes to a trail blocked by a fallen tree, he turns around, making a note to come back later with a chain saw. This land is a lot of work, and he's getting older. He's got to be careful. Another fall might be more than he can handle. They're thinking about downsizing. Building a small house and selling the big one to Jenni. Next year, for the first time in their lives, Dan and Kathy are spending January and March in Florida, returning to Iowa in February for wrestling events. They've rented a place. The sun will be a relief, easing Dan's aching joints. Here, surrounded by his forest, he has found the strength to finally surrender, which is its own kind of victory. To his left, five deer move through the trees. Snow piles on the branches, two inches at least.

Up ahead in the driveway, he sees his daughter's car running, coughing exhaust smoke. Mackie and Justin are about to leave, making the drive to Dubuque, where she teaches kindergarten and he coaches soccer. The reverse lights are on by the time Gable reaches the car. He leans in and gently kisses her on the forehead. Mackie's car disappears around the bend, leaving behind a red glow and then not even that. Everything is still. The house is empty. He'll know the fate of Olympic wrestling soon enough. His fighting days are nearly finished. Gable goes back inside. All he can do is wait for headlights to shine through the windows, letting him know one of his girls has come back home.

To the world, he's a champion. To his nine grandchildren, he is a jungle gym. Andrew Cutraro

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com. Follow him on Twitter at @wrightthompson.

Follow ESPN_Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader. Follow the Mag on Twitter: @ESPNmag.