In the Beginning, There Was a Nipple

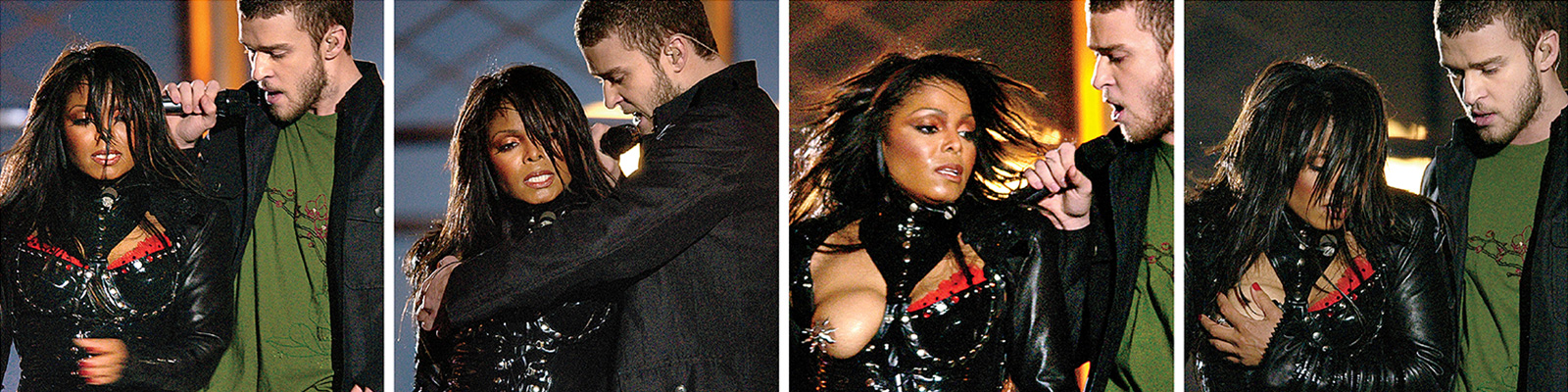

Ten years ago, 90 million people watching Super Bowl XXXVIII saw Janet Jackson's breast for nine-sixteenths of a second. Our culture would never be the same.

null

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Feb. 3 Music Issue. SUBSCRIBE

Editor's note: This story about Justin Timberlake's first Super Bowl halftime performance was published in 2014. Timberlake will again be performing at the Super Bowl this season.

IF OUR CHILDREN or our children's children ever dig up a time capsule from the beginning of the new millennium, they will find that in February 2004, America collectively lost its damn mind. Here's what they'll see: Janet Jackson on a stage in the middle of Houston's Reliant Stadium, wearing a leather kilt and bustier, surrounded by dancers in corsets and bikini tops and bowler hats and helmets, looking like a ragtag steampunk army of cabaret chorus girls and Highlander extras and BDSM enthusiasts. They're grinding their hips, Janet is caressing her corseted torso and 71,000 Super Bowl spectators are screaming themselves hoarse for the beatboxing of a 23-year-old white boy. Justin Timberlake emerges from an elevated platform beneath the stage in too-big khakis and a too-big jacket -- pfff-ti-pff-ti-chk! pfff-ti-pff-ti-chk! pfff-ti-pff-ti-chk! pfff-ti-pff-ti-chk! -- and a brass band blasts him into "Rock Your Body," a song from his first solo album. He and Janet are romping across the stage, pausing their cat-and-mouse game every so often to work her booty into his hips. They're singing call and response:

Talk to me boy ...

No disrespect I don't mean no harm

Talk to me boy ...

I can't wait to have you in my arms

Talk to me boy ...

They're marching up the steps, to a platform in the middle of the stage.

Hurry up 'cause you're taking too long

Talk to me boy ...

Better have you naked by the end of this song.

You know what happens next. Justin reaches over, grabs a corner of Janet's right breast cup and gives it a hard tug. Her breast spills out. It's way more than a handful, but a hand is the only thing Janet has available to cover it, so she clutches it with her left palm. The breast is on television for 9/16 of a second. The camera cuts wide. Fireworks explode from the stage. Cue the end of halftime. Cue the beginning of one of the worst cases of mass hysteria in America since the Salem witch trials.

Justin Timberlake never fully explained his role in exposing Janet Jackson, and Jackson said later she was upset that he remained mostly silent when people blamed her for Nipplegate. David Phillip/AP Images

THE WOMAN WHO planned the show wasn't on the field to see her months of work go up in flames. Salli Frattini, an executive producer at MTV, which was contracted by the NFL to produce the halftime concert, was supervising from the production truck outside the stadium. She and her crew were riding high on the adrenaline of pulling off a 12-minute spectacular of music and choreography and pyrotechnics. When it ended, the truck erupted with cheering and high-fiving and hugging. The euphoria lasted just a few seconds before the phone rang. The officiating booth was calling, wanting to know whether they'd really just seen Janet Jackson's boob.

The man on the phone was Jim Steeg, who had been head of special events for the NFL since the late 1970s, overseeing the evolution of the halftime show from a small-scale production featuring marching bands and dancing snowflakes and local heritage celebrations to full-scale rock extravaganzas starring the likes of Diana Ross, Michael Jackson and Aerosmith. When Nipplegate happened, Steeg was sitting next to the league's head of officiating, who was TiVo-ing the event. "He rewound it for me, and then I immediately called Salli," he says. "You could hear everyone screaming and hollering because what they pulled off and accomplished was over. I said to Salli, 'Did you see what just happened?'"

"We were like, 'Uh, we're playing that back right now,'" Frattini says. "There was lots of chaos in the truck, and we played it back and we were like, 'Oh, s -- . What just happened?'"

Frattini stepped out of the truck and immediately ran into then-CBS Sports president Sean McManus. He looked her in the eye and asked gravely, "Did you guys know?" Frattini promised she had no idea that Jackson was going to be exposed. "Okay. That's what I needed to know," she remembers him saying.

Whether Frattini or the higher-ups at MTV, CBS and/or the NFL knew what was coming remains one of the enduring mysteries of the event -- at least that's the generous explanation for why millions of people watched the clip with the same intensity as that of JFK conspiracy theorists poring over the Zapruder footage. To this day it remains the most watched video in the history of TiVo, becoming such a touchstone that "wardrobe malfunction" soon earned a dictionary definition and Nipplegate became a household word. (For the record, not much areola was even visible underneath Jackson's large starburst nipple shield.)

The common assumption by the media and by the public was that the flash of nudity was an attention-grabbing publicity ploy; the question was by whom. Some signs seemed to point to MTV. Before the show, a few of the producers had entertained themselves by mock-ripping their clothes off at Timberlake's final line. And in rehearsals, they had tried a move where Timberlake tore off Jackson's kilt. Then there was an article on MTV's website beforehand in which Jackson's choreographer promised "shocking moments."

To this day, everyone involved maintains the conspiracists have it wrong. The mock-ripping? That was their natural response to Timberlake's closing lyric -- "better have you naked by the end of this song" -- not in anticipation of anything he might do. The tearing off of the kilt? It didn't look good, so members of the production team say they killed it and never discussed another option. The article? The site was later updated with an editor's note: "At the time of this report, MTV thought that the 'shock' was going to be the as-yet-unannounced appearance of Justin Timberlake as part of Janet's performance. Janet Jackson's subsequent performance was not what had been rehearsed, discussed or agreed to with MTV."

In an on-camera apology after the event, Jackson backed up the producers, insisting she decided on the big reveal after the final rehearsal, without the knowledge of anyone at MTV. Timberlake was meant to pull off a piece of the costume, she later explained, but it was supposed to reveal only a lacy red undergarment; unfortunately, as it played out, that undergarment came off in Timberlake's hand too. Timberlake also apologized but never offered his own version of events other than to coin the term "wardrobe malfunction."

After the show, MTV producer Alex Coletti tried to find Jackson. "I tried to get in touch to make sure she was okay," he says. "Her entire camp stopped answering the phones. I finally got to her tour manager, and they were already at the airport." At first, Coletti assumed the singer was so mortified that she fled immediately. Then a new thought dawned on him. "No, she set us up and she's out of here," he says. "That was the last time I've seen or heard from Janet Jackson."

Ultimately, it didn't matter to the NFL whether the producers knew: The league decided that MTV would never again be involved in a halftime show. Says NFL corporate communications VP Brian McCarthy: "We turned over the keys to MTV, and they crashed the car."

On Capitol Hill, then-FCC chairman Michael K. Powell called the halftime show "a new low for prime-time television." Now he says the outrage was overblown. Michael Kleinfeld/UPI Photo/Landov

MICHAEL POWELL, THEN the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, was watching the game at a friend's house in northern Virginia. He's a football fan and was excited to relax and watch the game after a rough couple of weeks. "I started thinking, Wow, this is kind of a racy routine for the Super Bowl!" he says, his voice pitching up in bemusement. "He was chasing her kind of with this aggressive thing -- not that I personally minded it; I just hadn't seen something that edgy at the Super Bowl."

Then it happened. Powell and his friend gave each other quizzical looks. "I looked and I went, 'What was that?' And my friend looks at me and he's just like, 'Dude, did you just see what I did? Do you think she ... ?' And I kept saying, 'My day is going to suck tomorrow.'" Powell went home and watched the moment again on TiVo. The same thought kept running through his mind: Tomorrow is going to really suck, he remembers thinking. "And it did."

Typically, the FCC's work is of little interest to people outside of the community of businesses, lawyers, lobbyists and Hill staffers involved in telecommunications policy. But L. Brent Bozell had been on a mission to make on-air indecency a cause for national outrage, and Jackson's breast was his biggest opportunity yet.

Nine years earlier, Bozell had founded the Parents Television Council, an advocacy group dedicated to forcing advertisers, networks and the FCC to keep sleaze out of family-friendly TV programming. Just a year before Super Bowl XXXVIII, Bono, accepting a Golden Globe for best original song, called the moment "really, really f -- ing brilliant" on a live NBC broadcast. PTC members filed a complaint, triggering an FCC investigation. Nine months later, Powell's group determined that Bono's fleeting F-word didn't warrant a network fine. The PTC vehemently disagreed, and with its encouragement, members of Congress took to the House floor to call for action against indecency on TV. Two months before the Super Bowl, the Senate unanimously passed a resolution calling on the commission to reconsider the Bono decision (the FCC reversed its judgment in 2004 but still did not issue a fine) and to more strictly police indecency standards generally.

"We realized we'd really hit a nerve out there, and we weren't alone in this thinking," Bozell says. "That was all before Janet Jackson. Jackson was what lanced the boil."

Previously, Powell says the FCC received only a handful of indecency complaints a year. It received 540,000 about Janet Jackson's breast. The PTC launched a campaign to punish everyone involved. "An outraged public needs to make this backlash long and commercially painful," Bozell wrote in an article. "The NFL needs to back off its trend of treating its fans with the lowest common denominator of sleaze. CBS affiliates need to worry about license revocations if these offenses keep repeating themselves. And MTV ... ought to just be thrown out with the rest of the rusty garbage."

Powell, a Republican whose father is Colin Powell, the then-secretary of state, hates when people remember the Nipplegate controversy as Republican-driven. For one of the only moments in recent memory, Congress was united, passing a bipartisan bill increasing the maximum fine for incidents of indecency from $32,500 to $325,000. In a Texas congressional race several months after the Super Bowl, a Democrat circulated newspaper clips about his Republican opponent -- who'd written an op-ed decrying Jackson's behavior -- streaking as a college student.

Michael Powell himself immediately decried the show in no uncertain terms. "Like millions of Americans, my family and I gathered around the television for a celebration," he said in a public statement. "Instead, that celebration was tainted by a classless, crass and deplorable stunt." He announced an investigation of the show, promising it would be "thorough and swift." He made the rounds in the media to underscore his point.

Today, Powell runs the National Cable and Telecommunications Association, the major trade association for the cable-TV industry. He loves reading about the latest developments in behavioral economics, neuroscience and mindfulness. He's 50, but he looks no older than 35, dressed in gem-toned pants and glasses that look like they came from Warby Parker. Sitting in his office at the NCTA's sleek modern building in DC, he does not look like a man who wants to spend his time policing boobs on TV. He does not sound like a man who wants to spend his time policing boobs on TV. Since leaving the FCC in 2005, he has declined almost every interview request to talk about boobs on TV. But 10 years later, Powell is finally ready to admit that he never wanted to police boobs on TV.

"I think we've been removed from this long enough for me to tell you that I had to put my best version of outrage on that I could put on," he says, shrugging his shoulders and rolling his eyes. "Part of it was surreal, right? Look, I think it was dumb to happen, and they knew the rules and were flirting with them, and my job is to enforce the rules, but, you know, really? This is what we're gonna do?"

Powell was driven in part by fear: The indecency statute is part of the criminal code, so someone convicted of broadcasting indecency could be imprisoned -- as could an artist, at least theoretically. "As a leader, I thought that was really wrong," Powell says. "I didn't want this snowball, this juggernaut, to turn into pressure to go after Janet and Justin Timberlake. I thought we were getting into dangerous territory." Launching an investigation into the halftime production quickly gave him some ground to stand on when members of Congress started asking why he wasn't going after Jackson. Frattini and her team had to hand over their laptops; the government wanted access to every document and every bit of communication among the show's creators. The FCC found nothing to suggest they had planned the moment and settled on a combined $550,000 fine for the 20 Viacom-owned stations -- then the largest against a broadcaster in the commission's history. Powell ended up testifying on the wardrobe malfunction more than anything else in his entire career, including his confirmation hearings. "I ended up testifying for nine hours on just this," he says. "On 9/16 of a second."

OF COURSE, OUR children and our children's children will never need to dig up an actual time capsule to find out about the wardrobe malfunction. As soon as they hear about the time Janet Jackson's breast was exposed on live TV, they'll watch it online. And the reason they'll watch it online is that in 2004, Jawed Karim, then a 25-year-old Silicon Valley whiz kid, decided he wanted to make it easier to find the Jackson clip and other in-demand videos. A year later, he and a couple of friends founded YouTube, the largest video-sharing site of all time.

Across the web, the moment went viral, back when that phenomenon was still somewhat novel. (Facebook was launched three days after the halftime show.) "Janet Jackson" became the most searched term and image in Internet history. And "we put TiVo on the map," says MTV producer Coletti -- TiVo enrolled 35,000 new customers in the aftermath of Nipplegate. When Coletti was having trouble with his service, he let slip to a customer service rep that he was the guy who produced the Super Bowl halftime show. TiVo gave him lifetime service and a special number to call in case he had any trouble.

The moment created other seismic cultural changes as well. Howard Stern -- already a shock jock goliath with an audience of millions he built, in part, on testing the boundaries of the FCC -- was dropped from Clear Channel two months following the Super Bowl, after the FCC fined the company $495,000 for a broadcast in which Stern discussed "sexual" and "excretory activity." "Janet Jackson's breast got me in a lot of trouble," Stern told his listeners. Six months later, he signed a contract with fledgling satellite radio, framing the decision as an opportunity to break free from broadcast's conservative constraints. As of early 2014, SiriusXM had 24.4 million subscribers, and Stern is credited as the media figure most responsible for introducing a new era in radio.

While Timberlake's career as a solo artist took off after the Super Bowl, Jackson's suffered. When her album Damita Jo debuted the month following the halftime show, low play counts led to online rumors that she'd been blacklisted by Viacom, the parent company of MTV and VH1. The record was her lowest-selling album since 1984. She withdrew from the Grammys under pressure, while Timberlake performed and accepted two awards. Throughout the controversy, the bodice-ripped Jackson suffered much more than the bodice-ripping Timberlake. "I personally thought that was really unfair," Powell says. "It all turned into being about her. In reality, if you slow the thing down, it's Justin ripping off her breastplate."

Some critics saw gender and race at play and thought Timberlake ducked the heat. In a 2004 remix of the Jadakiss song "Why?" rapper Common asks, "Why did Justin sell Janet out and go to the Grammys?" Timberlake himself said he believed Jackson had taken a disproportionate amount of the backlash. "I probably got 10 percent of the blame," he told MTV. "I think America's probably harsher on women, and I think America is, you know, unfairly harsh on ethnic people." After initially apologizing for the incident, Jackson told Oprah in 2006 she regretted taking the blame for an unplanned accident. Informed of Timberlake's comments, Jackson smiled uncomfortably and confirmed that she felt her co-star hadn't done enough to defend her. "Certain things you just don't do to friends," she said.

Clearly, it remains a sore subject for both artists. Jackson told Oprah she would never comment on the controversy again. When recently asked by The Mag about what he had taken away from the incident, Timberlake laughed nervously as his representative signaled to end the interview. "I take that I chose not to comment on it still, after 10 years," he said. "I'm not touching that thing with a 10-foot pole," he quickly added.

Meanwhile, for the people behind the media spectacle, the controversy never really went away. After the incident, Frattini and Coletti both left MTV to start their own production companies. "That was the last year I did the [MTV Video Music Awards]," Coletti says. "I'd produced six VMAs, all the highest-rated ones at the time. And all of a sudden, I wasn't that guy anymore."

The incident transformed how they work too: Frattini says she's warier of talent, insists on knowing everything about their wardrobe before they perform and is careful to note every step of her production work in writing, cognizant that if anything goes wrong, government investigators may be reviewing her notes.

The wardrobe malfunction changed live television production too. Before then, most broadcasters employed audio delays only, but many began delaying video as well. The Grammys broadcast the Sunday after the Super Bowl used a five-minute delay, which Frattini says was an extreme example of a larger trend. Longer delays are more expensive and require more effort, but they became part of the cost of putting on live television.

Meanwhile, the NFL created contracts with more specific language about appropriate conduct, including wardrobe, and set stiff penalties for breaking them. The next six Super Bowl halftime performers were middle-aged men. One year after the league broke that streak with the Black Eyed Peas at Super Bowl XLV, M.I.A. raised her middle finger during Madonna's 2012 performance and was sued by the NFL for $1.5 million.

The most common assumption was that the flash of nudity was just an attention-grabbing ploy. The question was by whom. David Drapkin/AP Images

THE MOST LASTING impact of the wardrobe malfunction was the way it highlighted the government's inability to regulate indecency in our new digital democracy. The FCC has never had major control over regulating the media -- the First Amendment prevents the commission from having a say over what appears in the newspaper, on cable networks or online. But in 1978, the Supreme Court ruled that because broadcasting was "uniquely intrusive," the FCC had an obligation to regulate indecent content during the hours when children might be watching. The idea, Powell says, was that "you never know what's going to come on, and so your kid can be in the audience, and then boom! By the time they get hit with it, the harm is done and your kid is blind."

That gives broadcasters an amorphous obligation to act "in the public interest" and puts the FCC in the awkward position of judging indecency. It's hard to imagine a legal theory less well-suited to the modern era, when TV guides are as anachronistic as rotary phones because everyone watches on demand, online and on their phones. "The Internet and YouTube have exploded the notion of balkanized living rooms -- the Supreme Court's original thesis that you can have this sanctity of your home and nothing should be able to invade you in that way," Powell says. "I just think that's probably a bygone era."

As society has reached a consensus that there's no way to control everything children see, the number of indecency complaints has decreased significantly. When Miley Cyrus twerked at the Video Music Awards last summer, the FCC received only 161 complaints (of course, as a cable channel, MTV doesn't answer to the commission anyway). The moment became fodder for celebrity bloggers and morning show chatterboxes but was never treated as a problem that needed to be legislated away. The PTC dutifully issued a statement denouncing MTV for "sexually exploiting young women," but no national outcry resulted. Perhaps not coincidentally, CBS never actually paid a fine in connection with Nipplegate -- an appeals court ruled in 2008 and again in 2011 that CBS could not be held liable for the actions of contracted performing artists and that the FCC had acted arbitrarily in enforcing indecency policies. The Supreme Court declined to hear the case in 2012.

So for Powell, the halftime show represents "the last great moment" of a TV broadcast becoming a national controversy -- the last primal scream of a public marching inexorably toward a new digital existence: "It might have been essentially the last gasp. Maybe that was why there was so much energy around it. The Internet was coming into being, it was intensifying. People wanted one last stand at the wall. It was going to break anyway. I think it broke.

"Is that all good? Probably not, but it's not changeable either. We live in a new world, and that's the way it is.

"They said the same thing when books became printed, right? They said it was the end of the world.

"But it wasn't."

Join the conversation about "Wardrobe Malfunction."

Follow Marin Cogan on Twitter: @marincogan.

Follow The Mag on Twitter: @ESPNmag, and like us on Facebook. Follow ESPN_Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader.