A Town Torn Apart

A harsh western New York winter has finally given way to warm spring evenings, but the mood on the Wilson High School baseball bus is far from relaxed. One boy wants to learn jujitsu to defend himself; others want the bus to zoom up Highway 425 a little faster.

If Erik has learned anything from a year on the junior varsity, it's to be on edge. He is smaller than just about everybody else on the bus, aside from the head coach's kindergartner son who serves as a sort of team mascot. If something goes down tonight, he's going to be on the wrong end of it. Before he was stuffed into a locker, before his prepubescent, straight-A's world tipped over, he dreamed of playing for the Yankees. But now Erik hates baseball, dreads the bus ride, and just wants to hunker down at home and play Guitar Hero.

Earlier, he asked if his father could pick him up, avoid the bus. But his dad was working. Did the boy know, then, what was about to happen? He sinks into an aisle seat a few rows behind the driver. Hands grip his shoulders; another covers his mouth. He can't hold on.

When the bus finally pulls into the school parking lot, one thing is clear.

The boys, and their town, will never be the same.

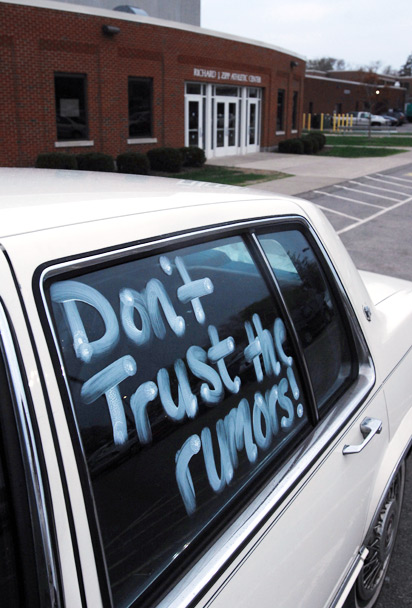

The rumors and whispers seeped through bookshelves, whipped their way around back aisles at the IGA, and blanketed barstools on Young Street. Everybody knows somebody else's business in a small town. The mayor has a daughter who owns a store in Wilson; the secretary at the elementary school is married to a member of the school board. Most folks like the coziness. The trust.

Transplants occasionally feel suffocated. One resident's introduction to Wilson's fishbowl existence came when she had car trouble. The family had just moved to town. She called AAA, and the voice on the other end of the line said he didn't need the address. "I know," he said. "You moved into the house on Chestnut."

They're neighbors, all 6,000 or so of them, distanced from the dirty realities of the city by trees, twisting highways and lush green farmland. This, where cell phones bounce to international roaming in the northernmost parts of town, is where you expect to find peace.

This is where Thomas Baia and William Atlas built their lives. Baia, friends say, is the man who brought soccer to Wilson nearly two decades ago. He's 40, has taught children nearly half of his life, and still has a boyish smile and a thick head of hair. If you have a problem, the old baseball alums say, you go to T.J. Baia and Billy Atlas, pillars in the baseball coaching community. They care.

Now, their careers hinge on something they apparently didn't do. They didn't turn around from their seats in the front of the bus on this random night, on one of the hundreds of school bus rides they've taken over the years. If they had -- if they had done something -- would they be lumped in now with the actions of a handful of teenagers? Would the events of late April have divided Wilson this way?

Baia and Atlas, by all accounts, love baseball, their teams and their town. Drive down Lake Street, months after the bus ride from Niagara Falls, and Baia can still be seen walking his dog along Route 18, between Lake Ontario and an empty ball field.

Two women fidget in a lawyer's office in downtown Buffalo in late June. One of them is puffy-eyed and looks as if she's been crying. They are friends now, like family, bound by one horrible secret that has at least 30 versions. Their sons sat together on Wilson's baseball bus that night. When the season began, Erik and Logan knew each other casually through T-ball. Now, months later, they're inseparable. Both boys, their parents say, were sexually assaulted by members of Wilson's varsity baseball team. Police reports indicate a third boy also was allegedly assaulted.

"I just have to ask," Erik's mother says to a reporter. "You're not going to use names?"

She knows that, by now, at least half of Wilson is aware that one of the alleged victims is her son, but she still hasn't told most of her family what happened. Nearly a week passed before either of their boys said anything about the incident; when they finally did, they begged their parents not to go to the police.

On the way to the State Police barracks, Logan, his mother says, bawled uncontrollably.

"He did not want to be known," she says, "as the kid who was raped on the school bus."

It has been their secret, and they say they want to tell it this way, in their lawyer's office. "Erik" and "Logan" aren't their sons' real names. They've been changed to protect their identities. The mothers did not bring their boys to this meeting. They say they don't want to subject them to reliving it, though they know their sons might eventually have to tell their stories in court.

Conor had just told his parents that he was scared, that he needed to learn some martial-arts moves from his brother, that Erik and Logan had been beaten up a few days earlier and that the big kids were saying he was "next." He didn't want anyone else to know. He didn't want to be a "narc."

"Conor stepped up and did a very, very unpopular thing," says Jeff Lynch, Conor's father. "He told his mom what was going on, and it blew it out of the water."

Word bounced from the Lynches to Erik's house to Logan's family. Within 72 hours, it was all over Wilson. On April 23, Logan's mother says, in the car on the way back from an orthodontist's appointment, her boy finally told her everything, how he'd watched Erik get plucked from his seat and disappear, how Erik had come back a few minutes later, disheveled and crying.

How Erik had turned to him and said, "That hurt so bad. I don't ever want to be gay."

Logan, his mother says, didn't know what he meant … until he too was pulled to the back of the bus a few minutes later. He'd moved to the aisle seat so Erik could be next to the window, and safer. Logan fought off the faceless grip once. Though he's only 13, he's strong, one of Wilson's best athletes. But the second time, he was swallowed up.

"Outside the Lines"

Three varsity players -- Geoffrey Seefeldt, 18, who also played football at Wilson, and two 16-year-olds -- have been charged with third-degree aggravated sexual abuse, a felony, and misdemeanor child endangerment. Court documents say they inserted a foreign object into the rectum of a male victim being held down on the floor of the school bus.

In an e-mail, Seefeldt's attorney, Mark E. Guglielmi, wrote, "Our client is anxious to address this matter, unfortunately, at this time we must decline your offer for an interview … We await our opportunity to present our case and for the facts to be heard by the Court. Our client denies the allegations and would like to bring closure to this most unfortunate matter."

Two notices of claim were recently filed by the victims' lawyer, Terry Connors, indicating a potential lawsuit against the Wilson school district.

One claim says that a varsity player sat on the chest of "John Doe 1" to hold him down, and that a cell phone was inserted into his rectum. It says the second alleged victim, "John Doe 2," was beaten, held down and had what felt like "multiple fingers" or a foreign object forced into his rectum.

Connors says his clients had their uniform pants on during the alleged assaults.

The claim says that hazing also took place in 2007. During that season, varsity players allegedly carried JV boys to the back of the bus, where they "pinned them to the floor, beat them, and placed worn, unlaundered athletic supporters over their noses and mouths, poked at their buttocks and rectums with various implements, abused their genitalia, and otherwise assaulted and battered them."

The varsity was still playing the night of April 17 when Logan leaned against his mother's car and asked for dinner money. She was proud of him that night. He'd made a nice catch. The bus would make one stop, at Burger King, and then they'd be home.

"I love you, Mom," he said. "Pick me up at school."

When Logan was little, his mother says, he dreamed about wearing a Wilson uniform. He watched his big brother play sports and ride the bus with his buddies, stopping for hamburgers on the ride home. He wanted to be just like them.

But when he stepped off the bus at Wilson that night, Logan told his mother he was quitting baseball because the varsity boys were "jerks." Then he said he didn't want to talk about it anymore. As their car pulled away, Logan and his mother saw a boy searching for something in the back of the bus. It was Erik.

What was he looking for? A shoe? Why didn't he say something?

"In my house, it's all open," Erik's mother says. "For me, I was floored. Why wouldn't this kid tell me?"

"He goes, 'Mom, it was so bad. I wish I would've died, right then and there. I wish I would've died,'" she says.

She starts to cry.

"And I said, 'Well, that wouldn't have been good for anybody.' I'm sorry. It's just … he's a good kid, you know?"

The newspaper said concerned Wilson residents would have a chance to speak on Thursday night, May 1. By 6:30, a half hour before the meeting, cars lined Highway 425 and clogged the back parking lots of Wilson High School. The auditorium wasn't big enough to hold the crowd. People spilled out to the gymnasium and watched on closed-circuit TV.

Two weeks after the bus incident, developments in this once-sleepy town were moving at a frenetic pace. Boys arrested, varsity baseball season canceled, two coaches charged with child endangerment and suspended. Cameras, everywhere, zooming in. Headlines blaring about hazing and sodomy.

"Too much of you," a man in an SUV barked at a TV camera. "Get the hell out of town. Leave us alone."

At the meeting, their meeting, it was their time to speak. Townsfolk got three minutes at the microphone to ask questions or vent. No cameras allowed.

A woman stood up and said she worried about her autistic son being harassed at school. A united front of young male athletes gave testimonials for their baseball coaches, and was saluted with long rounds of applause.

The alleged victims were rarely mentioned.

"The media took this and ran with it," one man said. "They took sex, violence and victims. They took an incident and turned it into assault. We made national news because of this.

"I'm angry, and I'd be willing to bet … I would be willing to bet most of the people in this room are angry. And I would be willing to bet some of them would like to take some of these reporters to the back of the bus."

Somewhere inside, behind the young, passionate men, sat the mothers of two of the alleged hazing victims. When the meeting ended, they quietly left the room, passing the hallway sign that reads, "Wilson High School: We do what we're supposed to do, when it is supposed to be done, to the best of our ability, and we do it every time."

The town of Wilson's criminal court meets every fourth Thursday night, when two judges arrive to hear traffic cases, random failure-to-appear excuses and the occasional DUI. The courtroom is a few steps away from the counter that issues dog licenses. The town hall sits directly across the street from the high school. Walk outside, and you'll see a message applauding Wilson's commitment to academic excellence.

Fifty-some folding chairs are carefully lined up for what promises to be a big night in late June. Wilson's baseball coaches, Baia and Atlas, and the three accused boys are scheduled to appear.

Supporters and reporters stand along the back and side walls of the courtroom. Wilson has beefed up security because of all the attention to this case, a court employee says. They added white shades on the courtroom windows to foil busybodies.

But by the time the session starts, the boys' hearings have been continued again. They've been excused. Baia and Atlas remain, though, sharply dressed in suits, standing out in the jeans-wearing assembly. Their part is anticlimactic, too. Their lawyers confer with the judge and step back from the front, and their legal business is finished for the night. Roughly half of the courtroom empties.

Baia, who has been Wilson's varsity baseball coach for seven years, shakes a few of his well-wishers' hands.

Outside, his father-in-law, Charles Stojak, speaks to reporters.

"This is a big waste of time," he says. "All because a couple of punks did something stupid … they're wasting a lot of time, money and effort."

This, townsfolk say, is the line that divides Wilson. On one side is 30 years of teaching. On the other is 30 minutes on a bus.

It could happen to you, teachers tell their colleagues as they defend Baia and Atlas. You can't see everything.

But New York State Police Lt. Richard Allen, whose department interviewed all 30 boys from the April 17 trip, along with alums from two previous seasons, says he's "fairly confident" that hazing had been taking place for at least two years under these coaches' watch.

"We believe this is not a one-time incident," Allen says. "It's been an ongoing course of conduct at the school -- not the sexual assault, but just hazing type of incidents on the bus where the varsity players may have tormented the junior varsity players a little bit. And we feel over time that this has progressed into the incident that happened on April 17."

Debbie Diez says Baia has known about the hazing for at least a year. Diez, whose son plays on the JV team, says she told Baia about it herself during the 2007 season, when some younger players -- including Erik -- were being "slammed around" by the varsity.

Diez was present, too, for an April 23 meeting that, like a lot of things in town these days, has conflicting versions. A close friend of Erik's mother, she was visiting the family's home that night when both sets of parents made the decision to call the police.

Baia and Atlas were there, too. Diez says the coaches asked what they could do to "make it go away." When the decision was made to call the police, Erik's mother says, Baia and Atlas quickly left.

Through their attorneys, Atlas and Baia say they went to the house, but only to offer support.

"I can tell you that there was no interest by either of these coaches to cover up what had taken place," says Herbert Greenman, Atlas' attorney. "As a matter of fact, Bill Atlas is the one who contacted his superior immediately when he found out about it. So it's not a question of wanting it to go away. I think that they were both concerned about what happened. I think that they were looking into the situation."

Baia's lawyer, Robert Viola, says his client is "heartbroken." Baia, he says, couldn't even attend his son's soccer games and had to get permission to be at the boy's kindergarten graduation because it was on school grounds and he is suspended. Baia recently stopped at a hot dog stand outside of town and struck up a conversation with a young boy. The kid's father darted over and pulled him away.

"He looked at T.J. and basically said to him, 'You're a sexual predator' or words to that effect," Viola says. "And, you know, if you put a knife through his heart, it probably wouldn't have hurt any more than that."

It eats at Erik's mother now, that she forced him to go. "You love baseball," she told her boy during the times he wanted to stay home but couldn't say why.

Erik and Logan have changed, their mothers say. The boys crawl into bed with their parents at night to sleep. They're nervous and anxious and need background noise to help them close their eyes at night. It's been this way since April.

"We had a wonderful day a couple weekends ago," Logan's mother says. "We went boating as a family. We went to dinner afterward. And somebody came up to my son, and I'm trying to hear what is being said, and it was about the baseball team.

"Instantly, my son had to go home. Daddy had to lay down with him and watch a movie, and everything … I mean, for a couple of minutes there, we were away from it all. And somebody, I don't even know who, came up to him and said, 'You're on the team, aren't you?'"

Keep things as normal as possible, the counselor tells them. When Erik finally decided to play baseball again, his mother hesitated.

"Mom, I just want to be a kid," he told her. "Can't this all go away? I just want to be a kid.'"

But they can't go back. Logan's mother says she drives 15 miles away from town now to go to the grocery store and do the banking. His grandmother took him into the IGA on Lake Street recently. Minutes later, he ran back to the car and wanted to go home. According to his mother, he said, "Nana! Do you know who that is? He was on the bus, Nana! He was on the bus!"

When she hears sirens wailing from down the street, Logan's mother wonders whether it has something to do with her son.

"It's like living in a country but not really being in it," Erik's mother says.

It has been suggested, by a counselor and others, that maybe the families should leave Wilson and start over someplace else. Erik's mother doesn't consider it an option. If they leave now, she says, her son will be pulled away from his friends and perhaps come to think he's being punished for the incident on the bus.

They have found private allies in unusual places. A middle-school teacher recently locked the door of her classroom and wrapped her arms around Erik.

"I support you," she said.

The accused teens finished the year in home schooling. One of them, a16-year-old, is working a full-time job this summer, then goes directly home. He knows who his friends are, the family lawyer says.

"I think there are lines being drawn in Wilson," says Kevin Shelby, the 16-year-old's attorney. "Lines that back up the different actions that have developed. He's in the middle of this firestorm, and he's completely restricted. He doesn't do what he used to do."

The boy's legal troubles aren't isolated to April 17. Three weeks later, he was walking through the back parking lot of a car dealership with some friends at 1:30 in the morning and was stopped by sheriff's deputies. As he was patted down for weapons, the deputies reportedly found a white powdery substance in his pocket and two pills that Shelby's client identified as hydrocodone, a prescription drug for pain.

Shelby told the local media at the time that the boy was being targeted because of the Wilson case. Shelby and Andrew Vona, the lawyer for the other accused 16-year-old, say their clients participated in a form of group harassment of other boys on the bus, but it never reached a sexual nature.

Their lawyers worry about the boys' being identified as sex offenders for the rest of their lives. The Niagara County District Attorney's office recently extended a plea offer to the lawyers of the accused, Shelby says. The boys -- as well as Baia and Atlas -- are expected back in court later this month.

"My understanding, from all the information I have, is that this type of conduct with the bullying and the physical contact has gone on for some time," Vona says. "I certainly don't think it is something that is unique only to Wilson. But again, I think it was situations that were on the bus that were … not intended to be in any way violent or anything other than high school kids doing what a lot of high school kids do."

Shelby says he requested medical records from the district attorney's office two months ago but has yet to receive any. He says it leads him to believe that there is nothing to be seen.

"It was overcharged, and then it snowballed, you know, with the local media and press," Shelby says, "and I can't blame them. The way it was released … you hear the term sodomy or violation with a cell phone with 16-year-olds, it's going to get somebody's attention.

"My client, he's extremely likable. He's got a na´vetÚ about him. He's a genuine person, not some kind of thug wearing a baseball cap sideways. He's a nice kid, and I want to see it work out for him."

Wilson's school district superintendent, Michael Wendt, sits in a trailer on campus, flanked by an attorney, a public relations specialist and two school officials. He says he wants to talk about how the school handled the bus incident. He's dying to talk. He says he'll discuss it with his group and they'll decide whether he can speak publicly.

Eventually, the school sends an e-mail:

- It is the policy of the Wilson Central School District not to comment on pending legal matters and this situation is no exception to that rule. The allegations are very serious and the District has cooperated with law enforcement authorities and will continue to do so. We look forward to the resolution of these issues.

Connors' notice of claim says that the district repeatedly ignored cries for help from the younger players and that the respondent "knew or should have known that dangerous, tortious behavior might occur on the bus rides."

The families, Connors says, sent their kids to school and expected them to be protected. When the boys were abused, he says, they didn't know where to turn.

In the days immediately after the April bus incidents, when the town gathered for its meeting, Wendt had been more revealing. He held a news conference and said that a task force would be formed to deal with harassment and intimidation, and that the school had already begun placing other adults on buses to keep the kids safe.

A summer ago, Wilson made headlines in The Buffalo News under much different circumstances. The school's 16 varsity sports teams earned a New York State Public High School Athletic Association's Team Scholar-Athlete Award.

"What I can tell you is I'm the superintendent; I feel I failed the district," Wendt said the night of the town meeting. "I feel that to some degree, this was under my watch. Did the district fail? I think that certainly remains to be seen.

"You could see the passion pouring out for the coaches, the passion pouring out for the kids. I think that it was remarkable what we saw tonight. There are two sides to every story. And these are seasoned veterans. My kids have been coached by these coaches. But I still think we need to remain vigilant and wait and see what the investigation turns up in regards to [Baia and Atlas]."

Through younger eyes, maybe it isn't that complicated. D.J. Littere, a solidly built infielder for the JV team, watched the boys' reactions, the fear on their faces, when certain varsity players boarded the bus back in April. He saw Erik return to his seat that night, and heard him say, "I can't believe that just happened."

"If they let that happen on the bus … ," Littere says, "and that's just on the bus. If something happens in school -- if they had the same reaction to what happened on the bus -- I don't think [the coaches] should keep their jobs."

A man stands outside the T&R station while the price of gas changes again with a couple of jabs of a pole. He knows some of the boys whose names have been whispered around town since late April. They've come in for pop and candy. It's the only gas station in town.

"The thing is, kids don't have anything to do here," the man says.

The bowling alley closed years ago and sits cobwebbed on the edge of town. Young men pass their summer nights by skateboarding in the fire department's parking lot. Come winter, a good portion of the town's shops close down. Baseball is a temporary reprieve.

When the JV season starts up again, minus the varsity, the team is run by a teacher named Scott Benton, a smiling lug of a man who wears short sleeves in frigid temperatures. Benton, under orders from the school district, can't talk about what it's like to try to heal the wounds. He says only that he lives next door to the school and that he loves the kids, loves Wilson.

It's the season finale, a road game on the outskirts of Buffalo, and it's obvious that playing for Wilson, one of the smallest schools in Niagara County, has its disadvantages. Wilson's boys are young, and their opponents out-size them. A man-child slugger knocks a Wilson pitch and lumbers around the bases. The Lakemen fall into a big hole.

In the last inning, Wilson fights back and almost ties it.

"They don't quit," a parent from the opposing team says. The woman keeping score for Wilson looks up from her book and sighs.

"It's been a long season," she says.

A month earlier, Benton convinced Erik to play again. The boy said he was quitting, that he couldn't face this. And Benton told him that was fine. But he'd keep his uniform in his locker, leave it hanging in case Erik decided he wanted to come back. "Nobody wears that uniform like you," Benton said. Erik returned to the team and finished out the year.

"It was sort of just like starting over," Littere says.

After the game, another loss, the boys walk up to Benton, one by one, shake his hand and thank him. He pulls them together and says they'll make two stops on the way home -- at Mighty Taco and McDonald's. He makes a joke about the nutritional value of McDonald's. The boys laugh. They head to the bus, which is half-empty now. They walk.

Elizabeth Merrill is a senior writer for ESPN.com.

Join the conversation about "A Town Torn Apart."