This is part of a seven-story package assessing the state of the young NFL quarterback. Look for more on Jameis Winston, Marcus Mariota, Johnny Manziel, Andrew Luck, Andy Dalton, Cam Newton and others in ESPN The Magazine's How to Raise a QB Issue, on newsstands Nov. 13. Subscribe today!

ANDREW LUCK FLINGS a wet sock over his shoulder and stares at the drab carpet in the visitors' locker room at Carolina's Bank of America Stadium. His backup, Matt Hasselbeck, leans over and hands him a towel. "How'd you come out?" Hasselbeck whispers, which is what he usually asks Luck after a game to make sure he's not injured, or any more injured. But on this rainy night that burns into morning, Hasselbeck says it mostly as an icebreaker because he has no clue what to say.

It's the first week of November, and the Colts have just fallen 29-26 to the Panthers in overtime, Luck's fifth loss in six starts. As in most games this season, he took way too long to get going, showed flashes of his old self at the end, then reverted to 2015 Andrew by throwing another interception. This one, on Monday Night Football, was surely the most crushing.

Longtime Indianapolis columnist Bob Kravitz says he's never seen Luck so dejected.

Through his first six games, Luck had as many turnovers as touchdowns. He's injured, maybe with some broken ribs, definitely with a bad shoulder. Before the impressive win over Denver in Week 9, Luck had the league's lowest passer rating among starters (71.6), led the league in interceptions (12) despite missing two games and looked beaten down and mortal.

"The only thing I can say is he's trying really hard," Hasselbeck says. "He might be trying too hard."

We aren't used to seeing Luck like this. He once seemed to have it all figured out, starting as a rookie from Stanford. He led the Colts to 11-win seasons and the playoffs in each of his first three years. But now it's Year 4, and everything has gone to hell.

PERHAPS THE BEST place to find out what's wrong with Luck is in a sprawling building in downtown Indianapolis, up a flight of stairs to a nondescript office where his father, Oliver, agrees to meet. The similarities in their voices and mannerisms are uncanny. Oliver once played quarterback in the NFL too, so he gets it. Sort of. The elder Luck spent most of his career backing up Warren Moon, so he didn't exactly face the white-hot scrutiny Andrew is enduring now. But Oliver recently took a job as the executive vice president of regulatory affairs with the NCAA, and the move to Indianapolis has allowed him to grab dinners with his son and a front seat to the Colts' 2015 season. He has watched him throw interceptions, get booed, injure his shoulder and lose games.

Nothing seems to be in his son's control. External pressures he once overcame seem to be closing in on him. A Colts offensive line that was subpar from the beginning has gotten progressively worse. Offseason acquisitions that were supposed to bolster his supporting cast have been a bust. Desperation has hung thick in the Indiana air since the start of the season, and it's caused embattled coach Chuck Pagano to make some desperate moves, most notably a backbreaking fake-punt fiasco in a mid-October loss to the Patriots. Offensive coordinator Pep Hamilton, fired on Nov. 3, the day after the Panthers game, is the latest fall guy, and he likely won't be the last.

Luck's pocket, figuratively and literally, is collapsing. He's been hit more times while throwing than any other quarterback in the NFL over the past three and a half seasons, according to ESPN Stats & Information, and it's finally taking its toll. Before 2015, Luck hadn't missed a game since his freshman season at Stanford. This season he sat out Weeks 4 and 5 with a shoulder injury, and Fox Sports recently reported that he has been playing with broken ribs.

How will his body, and his confidence, survive the rest of the season? Can he lead the team back?

Andrew Luck says little beyond "I've got to play better," and Oliver does not want to elaborate on conversations he's had with his son about his struggles. Adversity comes through a hundred different doors, he says, and he insists his son has faced plenty of it before. NFL careers aren't linear. They're like stocks. They go up, and sometimes they go down.

"He wouldn't say [he was frustrated] even if he were," Oliver says. "Even if he did, I wouldn't tell you."

Oliver would much rather talk about what book he's reading. It sits on the corner of his desk, about one-third finished. He stole it from his son's library. It's called Rust: The Longest War, and both father and son insist it's fascinating. Oliver says rust is one of this country's most pernicious forces because it eats away at and destroys the infrastructure, the bridges, airports and railways. It's inevitable. Corrosion eventually wins.

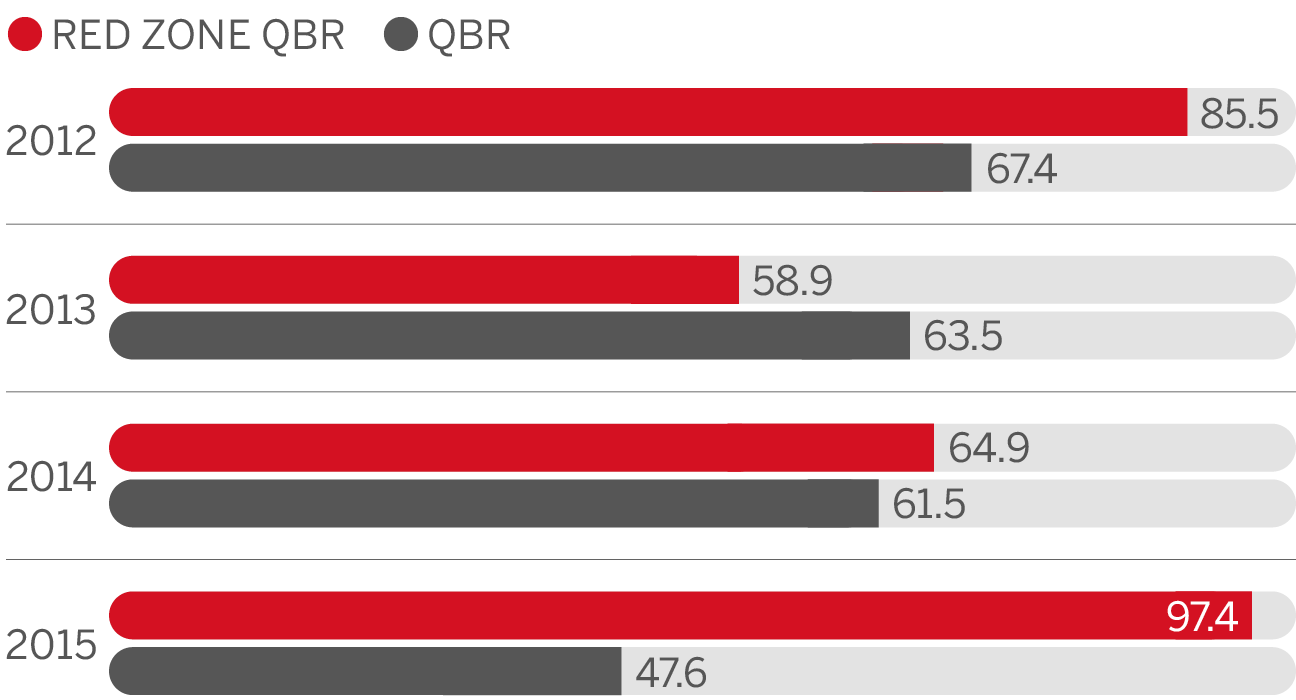

Luck's next-level numbers over first four seasons

YEAR 4 IS supposed to be the time when a young quarterback comes into his own. If he's lucky, he's spent much of his first three seasons behind a veteran, learning the ropes just like Hasselbeck and Aaron Rodgers did. It's also a year in which even the best quarterbacks can come under a lot of heat. Both Tom Brady and Peyton Manning struggled in their fourth seasons. Manning threw four interceptions in a game that year, and Jim Mora unleashed his infamous "Playoffs?" tirade.

"I don't think it's like a pyramid," Hasselbeck says of a quarterback's life cycle, "like you're good, you're a little better, you're great. Sometimes you have a great year and sometimes you don't. You're so dependent on your teammates, your defense, your special teams, your offensive line, your playcaller. If you can get through a year and you're healthy and your O-line is playing well, that's nice. But that's super rare."

In many ways, Luck reminds Hasselbeck not of Manning or Brady but of Brett Favre. As a young player in Green Bay, Hasselbeck watched Favre's interception reels, and at some point someone in the film room would always say, "Ahhh, that was a dangerous play. You shouldn't have done that." Then they'd watch the touchdown reels and say the exact same thing.

Luck's DNA is part of his problem. He's a stand-and-deliver quarterback. He takes five-step and seven-step drops, which puts more pressure on his line. He is not conservative. He is prone to mistakes, and he has success because he attempts difficult throws into tight windows.

The fact that Luck is throwing a lot of interceptions this season should surprise no one. He's always done this. But in the past, they were usually followed by 10 spectacular plays and another victory, so nobody noticed.

It's clear his injuries have affected Luck's play. Greg Cosell, a senior producer at NFL Films, believes Luck shouldn't have played in Week 6 against the Patriots because he didn't appear to have his natural arm slot with his full range of motion. "I don't think he's gun-shy," Cosell says. "The larger question is, Will his body wear down sooner than later? In other words, instead of a guy who we might look at and think, 'Oh, he can play for 12 or 15 years,' is he going to be worn out in year six or seven and maybe not the same player?"

In the spring of 2014, Luck went to San Francisco to talk with mobility guru Kelly Starrett about active recovery and how to survive the constant hits in football. Starrett told him about compression socks, hydration and sleep hygiene, and Luck took copious notes. Luck has long been reading and researching ways to make himself better. He arrives at the team facility at 6:30 each morning just so he can complete his pre-workout routine, preparing his body for the weekly attack it's about to face.

Former Colts backup Chandler Harnish, who accompanied Luck on that trip to San Francisco, says that even before 2015, Luck played through many injuries that would have sidelined other quarterbacks.

"He's criticized for turnovers, but that guy has carried that team," Harnish says. "I think it's pretty evident he's carried that team for four years now. I think maybe the hits are starting to add up a little bit."

IN MARCH, LUCK decided to unwind by going on a USO tour. He threw a football on a C-17 as it cut through the air over Afghanistan, and he hung out with James A. "Sandy" Winnefeld, who at the time was a Navy admiral and the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

"What do you do when things aren't going well?" Luck asked.

"You keep your head down, fix the problem and grind on," Winnefeld told him.

Flash forward to Week 5. Luck has to sit because of his shoulder. He hovers over Hasselbeck in a training room in Houston before a Thursday night kickoff. Hasselbeck is doubtful after getting sick from some bad chicken.

Luck stands over him. Hasselbeck has an IV in his arm. Luck buries his mouth in his shirt and simulates the choppy headset transmission.

Scrappy right cram, key left, Z-9-X Dickey Y Apache.

"Scrappy right cram, key left, Z-9-X Dickey Y Apache," Hasselbeck repeats in a daze.

They have been a perfect match, the cool 40-year-old Hasselbeck who's hanging on because he wants a ring and loves Luck, and the nerdy superstar who's in the early chapter of his career.

Once a week during the season, the two quarterbacks go out to eat together. Luck is a big foodie who's always trying to introduce Hasselbeck to new things. The Saturday before New England, they went to a place called Recess outside Indianapolis and had, among other things, yellow fin from New Zealand. Hasselbeck was still a bit wobbly with a bad stomach, but he ate anyway.

It was hours before a gigantic matchup between two teams with plenty of ill will toward each other, but Luck didn't talk about New England, or his struggles. They laughed and relaxed and played rock-paper-scissors to decide who paid the check.

Books are about the only things that make Luck light up when he talks these days. In late October, he offers a quick locker room review of West of the Revolution, a historical look at 1776 -- "It's a little dry" -- but declines to discuss his on-field frustrations. Keep your head down, fix the problem and grind on.

LUCK IS THE 10th player into the locker room after the loss to Carolina and still hasn't emerged after 1 o'clock Tuesday morning, when most of the team has headed to the buses. He puts the loss on himself. He always puts the losses on himself. As Luck showers, Hasselbeck is asked whether the young quarterback's confidence is battered. No. "It's cliché, but people say football's a game of inches," he says. "There's a fine line, and it's not a big difference of being on the right and wrong side of that line. In 2012, this team was barely on the right side of that fine line. That team seemed to find a way to always come through. I don't know." This year the line is jagged. But it still could be headed somewhere because the Colts' division, the AFC South, is the worst in the NFL.

When Luck finally emerges from the locker room, he'll hear a story from Hasselbeck on the bus. Maybe it will be about one of his worst moments in the NFL. Hasselbeck got booed in his own stadium, and the Seattle crowd was chanting Trent Dilfer's name. Dilfer, the backup, told Hasselbeck that a similar thing happened to him when he was a starter. It made Hasselbeck feel better.

He was in Year 4.