gold Honda CR-V pulls up to the corner of Waveney Street and Cadieux Road just after dinner on a lush autumn night. There are 24 wooden discs in the cargo hold. Each one weighs 5 1/3 pounds -- hard sugar maple shaped back in the early 1970s to resemble wheels of Edam cheese. The discs have been meticulously sanded and refinished over the summer with half a dozen layers of polyurethane oil.

The driver, Erik Greer, is one of those kooks who believe in Detroit. Not the chrome-plated motor city that once was, nor the make-believe version the Super Bowl ads say is roaring back. Greer, 56 and moving like an aging shortstop, is the sort of guy who, when the night feels just right, will shout, "Down goes Frazier!" He believes in Detroit. Right now. As is. And if that doesn't make him enough of an anomaly in this world, he also believes in American featherbowling.

Featherbowling was born from that medieval family of games that endure in no small part because they can be played with a beverage in the shooter's free hand. It's Belgian shuffleboard. It's horseshoes with a pigeon feather target. It's bocce, except you roll discs that have been slightly weighted to rotate unevenly across the earth, exposing the shooter's secret divine grace. It's pétanque, kubb, mölkky, curling, Cherokee marbles, Irish road bowls -- the variations are endless -- but none has the otherworldly mystery of this thing they play at the Cadieux Cafe on the east side of Detroit. That 60-foot downhill triple breaker Tiger Woods nailed on the 17th hole at TPC Sawgrass in 2001, which sucked every last atom of karma out of the air around it -- that's every sixth shot in featherbowling. You shout op de pluim when your ball snakes through the gantlet of other fallen wheels, wobbling like a wounded buffalo nickel, before settling on the feather.

Which is to say, it's a game in which tiny prayers are repeatedly answered, accumulating over time, until something is answered that nobody had even known to pray for. Thus a line forms outside the bar around Greer's CR-V, while inside a 20-piece oompah band shifts into "The Star-Spangled Banner" and then the Belgian national anthem -- "La Brabançonne" (which also happens to be 0519 on the jukebox) -- and 50, maybe 60 men pass the wooden wheels from one set of hands to the next, like buckets of water to a fire, past the Manneken Pis figurine and Eddy Merckx memorabilia, steadily around tables piled high with Prince Edward Island mussel shells, the gathered crowd clapping and stomping as the trumpets come to life. Each wooden ball goes all the way to the back, where half-filled chalices of something that translates as "Devil" sit on the counter, then through what appears to be an exit door and across a battered threshold.

Behind this exit door, long fluorescent bulbs illuminate two 72-foot dirt trenches. Nobody knows exactly how the trenches came to be. Men from the Old World would come in at all hours, tending them like the infield at the old Tiger Stadium. Building and pouring, hip deep in overlapping generations of misplaced earth. There's no floor beneath the trenches. "For all we know, they could go all the way down to China," says Ron Devos, a guy who grew up sleeping on a cot in the back of the bar. His dad was a painter and a pigeon fancier who acquired the onetime speakeasy in 1962, and Ron has spent the past half century trying to divine the provenance of the playing surface -- sand, clay, salt water, cat litter, ox blood -- God knows what else those old Belgians thought to mix in over time. In the afternoon before opening night, he feeds each trench half a bucket of sawdust, pausing to make sure the pigeon feathers are flush at each end.

There is a map of Belgium painted on the wall. A sparse list of the rules ("no high heeled shoes," "no lofting of balls"). The Packers are playing on a small TV, which nobody looks at twice. There are a couple of tattooed bikers in the corner. There are dudes in snazzy newsboy caps and dudes in Tigers hats, rims painstakingly worked in. There are white dudes, black dudes, hippies, veterans, ditch diggers, architects, lawyers, criminals, doctors and alcoholics. There are kilts, shorts, frayed jeans, office slacks. Some dudes are thumping their chests as some silently absorb every bit of the moment. And because it's opening night of the 2014 season, there are ladies there too. A voice, with the zeal of the guy from "Thunderdome," bellows, "Ladies and gentlemen, LADIES AND GENTLEMEN ..."

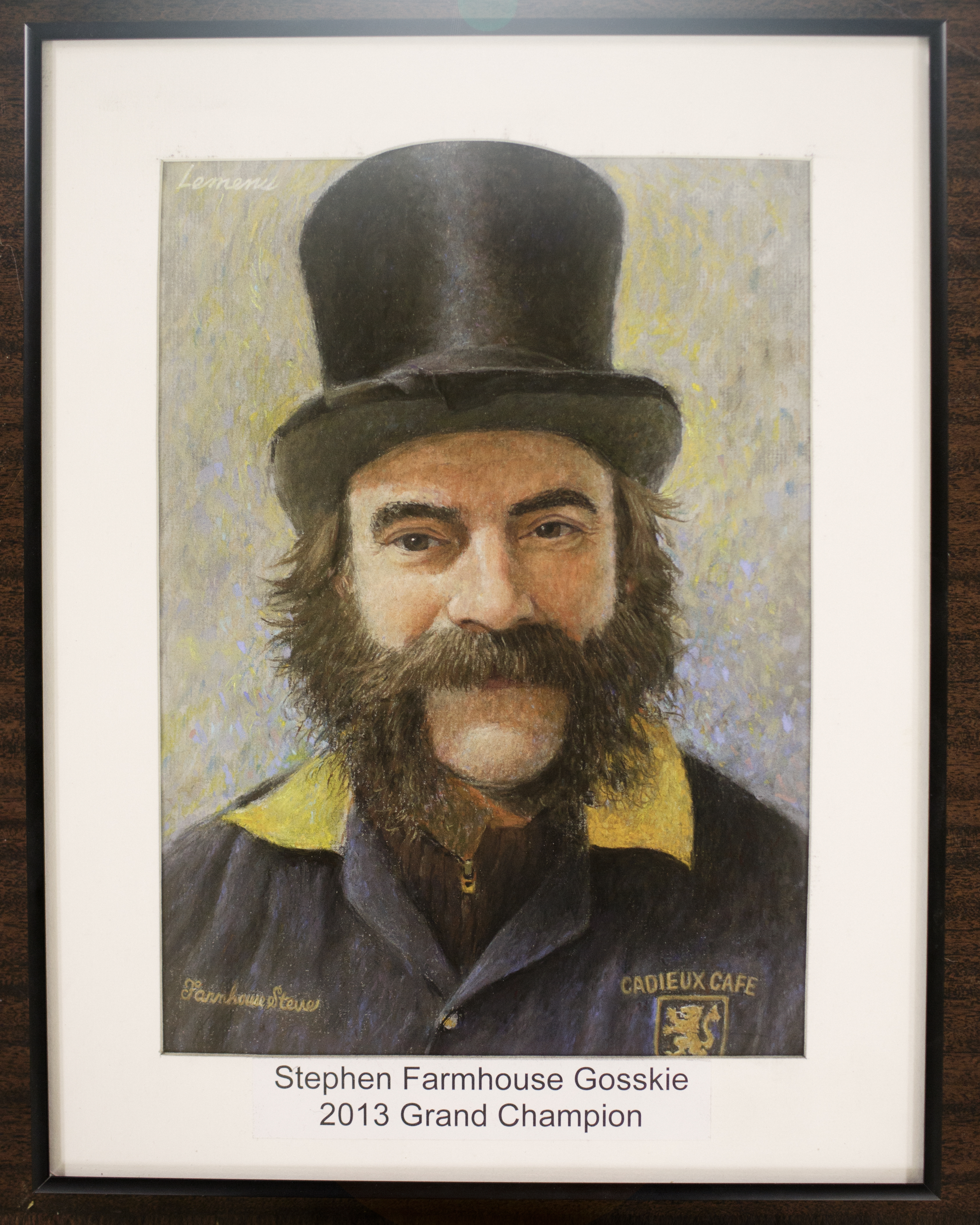

Greer, the president, is introduced. He directs the crowd's gaze up to the wall above the first trench, where portraits of grand champions hang. A yellow rag from the kitchen covers the painting at the far right end, just beneath the pressed tin ceiling. At Greer's signal, the rag is pulled, revealing a Dickensian character -- half wolf, half Abraham Lincoln -- pork chop sideburns and blinding black stovepipe hat leaping out from gnarly Van Gogh swirls. It's a portrait of the one they call Gosskie. Lips quiver. Tears well. A herald trumpet blasts the call to post. Names are pulled from three compartments of a small wooden box. Teams and matchups are set. And the men who come every Thursday to the Cadieux get down to work.

Step inside Cadieux Cafe, one of the few locations in the world that houses the unique sport known as "featherbowling."

THROUGH THE YEARS, the old Belgians would study the dirt like paintings on a cave wall. Each trench is its own living thing. The bowlers would patiently walk the intended parabola of the balls they roll so their teammates would understand what they saw, shuffling up and down the dirt like telemark skiers. You can't travel the path until you become the path. Depending whom you ask, a perfectly executed shot represents basic calculus, or else some visceral kind of pilgrimage across a Ouija board. Marc Tirikian, the most dangerous featherbowler in America entering the season, is an architect who sees sine waves. Add more velocity for a tighter arc, less for more.

Greer's vision is rather more complicated. Like Tirikian, he develops equations for specific apogees. But he does a metaphysical calculation too. He works nights at an Air National Guard base outside the city and likes to come a couple of days before opening night, before Devos adds the sawdust. He'll pour a stream of beer along the dirt, looking up to the portraits, asking for help in seeing the lines. He's had CAD sketches made to understand the complexity of the three separate radiuses inside each wooden ball. To understand the curvature of the trenches, he once took their measurements to a math professor at Wayne State.

Three weeks before opening night, an upper-level storm raced north across Michigan, where it ran into an unusual amount of moisture that had gathered in the air, and the second biggest rainfall in Detroit's history was recorded. The trenches absorb every calamity from the neighborhood outside, including the high water. Early in the night, bowlers would pick up on a small lesion 4 feet from the feather, about even with the cigarette machine, meaning a shot that appears ready to stop will suddenly dip down behind the feather, all the way to the back gutter like in a rigged carnival game. A couple of first-class bowlers find another dip 4 feet ahead of the first one. The first games of the night are havoc, everyone trying to factor in these new polyps growing from the path. "The perfection of our game is in the imperfection of the lanes," Greer likes to say.

For decades it was thought that only the old Belgians could read these imperfections. And not just any old Belgians. Those from a small region in West Flanders. It was as if those Flemish men had been born, like swamp monsters, from the trenches on Cadieux Road. A grand champion needed this blood, it was thought, and for generations there seemed to be an invisible asterisk beside anyone who won the title but wasn't from that direct line.

In 1976, Michael Chateau arrived at the Cadieux for a reception that followed the funeral of his friend Jerry Lemenu's mother. Chateau had never encountered such a world. He found himself returning to it, again and again. Many of the old Belgians had been active in the Resistance during WWII. One night, he listened as one of them read aloud from the Gazette van Detroit, a small ad taken out by a pilot from from Mishawaka, Indiana who had been shot down over a village. He was hoping to find the teenager who had tracked the fallen plane and helped him to safety years before. "That was me," Henry Verlinden, one of the bowlers, said nonchalantly. Sure as hell, the pilot showed up at the Cadieux a few weeks later and bought Verlinden a beer. "It was almost like this sacred thing to join," said Chateau, who came on Thursdays -- league night -- for six straight years before he gathered the nerve to ask whether he could play.

Tirikian grew up in the neighborhood. He left for college, then to play professional soccer in France. Then, when everyone he grew up with was fleeing Detroit, he moved back and dedicated himself to featherbowling. He won his first grand championship in 1998. His dad was killed less than a year later, just outside the Cadieux. Every Thursday he has to walk by where it happened. Nobody questions the blood Tirikian has in this place.

Up 6-2 against Greer on opening night, Tirikian would have a shot to end the game. From 60 feet away, Greer begins humming what sounds, at first, like some jangled kind of techno. As the humming becomes more emphatic, it sounds more like something from Dr. John's "Right Place Wrong Time." Greer is effectively trying to place a voodoo hex on Tirikian's last ball, something he conjures no more than three times in a season. As the humming hits a fever pitch, Tirikian's promising up-and-down seems to suddenly get sucked into the pile and away from the feather. Greer flings his arms up in triumph and shakes his head in disbelief. "It never fails."

Belgians once studied the dirt trenches like paintings on a cave wall, trying to read and re-create all their imperfections. Andrew Cutraro

AT THE BEGINNING of the 2012-13 season, Greer had begun to see the underlying system that connected it all. He had gotten off to a perfect start that season. Five games. Five wins. Fifty points. And then the most inexplicable thing to ever happen to American featherbowling happened: Steve Gosskie.

Around the neighborhood, they called him Farmhouse Steve because he lived in one of the 19th-century creakers just down the street from the Cadieux. He lived with Weezie, a beagle who was part Rottweiler and part lots of other things; he found her chasing butterflies near the abandoned Eloise Asylum. Gosskie was a magnet for all the city's Weezies.

He existed in that distinctly Detroit nebula of artists and machinists and miscellaneous rounders who'd make music and work relentlessly restoring broken-down mansions, only to stay up all night arguing Tesla versus Edison, tinkering with old engines. He'd drink after work with friends, covered in soot and asbestos and lead from crawling up into secret crevices, yanking on the tentacles of the rotting city. He liked to joke how the asbestos was cotton candy, the lead chocolate. You get a little delirious hauling a hundred pounds of cotton candy from those empty houses on a cold afternoon.

Gosskie had been hanging around the Cadieux as long as anyone could remember, and he felt a little bit like the league's mascot. He was 5-foot-7 and forever trying to cajole his shots with gestures after they'd been thrown. As an intense game would take shape, he'd inch lower to the ground, sometimes getting all the way down on his stomach. He stepped into his shots, his fingers digging into the trench just before the release so he'd have to spend the next day scrubbing dirt out of his nails. He was what they call a third-class bowler. Nobody took his game too seriously. Nobody knew how badly he wanted to be great.

But, like Greer, five weeks into that 2012-13 season, Gosskie was also undefeated. He stopped shaving. He didn't cut his hair. He'd have primers in the farmhouse with Weezie before he bowled. Blast Max Roach records. He'd build this rhythm that was at once organic and mechanical.

“I love the ricochet, and I’d get that click, bounce and snap, and then you’re on the feather.”

- Steve Gosskie

Games go to 10. You want to win each game every week, but it's total points that count through the season. Lose 10-9, you're going to have to buy the beer after. Get skunked 10-0 a couple of weeks early on, and you can kiss the grand championship goodbye. The accomplished featherbowler is playing a contest that spans not just the season but years and even decades. Third-class bowlers such as Gosskie tend to have less experience and a lower set of expectations. And so, nine weeks into that magical season, when Gosskie still hadn't lost, a couple of the older bowlers realized something was happening.

It was something like witnessing Mark Fidrych pitch at Tiger Stadium in 1976. Gosskie would hurl wheels recklessly, leaping to his feet, contorting his limbs and body like a maestro, directing the shot through impossible passages and chicanes. It was as if his entire life force had entered the wooden ball. "A lot of guys saw it as accidental," he said later, shrugging his shoulders. "They'd say I'm coming in too fast. I love the ricochet, and I'd get that click, bounce and snap, and then you're on the feather." He began calling his shots -- just so people would believe they were intentional. "Sometimes, man, you get this lumber pile, and you throw the bejesus out of it -- it's got a kinetic punch." He'd point at the spot where two balls came awkwardly together and a third was up on its side. He'd draw in a long breath, like he was going to try a shot, but instead start humming the theme from "The Dukes of Hazzard."

Gosskie harked back to some more remote age. He was born in 1967, basically the moment Detroit's decline began. "By the time I was able to rub my eyes and look around, it was already kind of rough," he said. As a kid, he delivered the Free Press in the morning, The Detroit News after school. He'd save his last parcel for the Cadieux. There was so much cigar smoke you could barely see across to the other side. Some afternoons, one of the Belgians would let Gosskie and the other newsboys go back to the trenches. Alone, nobody watching. "We would just set stuff up."

He learned to bowl on the house balls, which had been up and down the lanes for 60 straight years, each amassing thousands of miles, slamming against the piles, gaining its own pocked shape. When he finally joined the league in 2009, it took time to adjust to the magical balls the regulars waxed and worshipped.

By March 2013, he was up 12 points with five weeks to go. He simply couldn't be beaten. Meanwhile, Greer's season had gone off the rails. But that didn't seem to matter. Gosskie was proof of the divinity in what Greer had taken to calling "our game." See the line? Gosskie goddamn was the line.

Maybe, above all, he understood better than any of them the earth from which the trenches were constructed. As a newsboy, he'd been on and under every porch in the neighborhood. He had apprenticed at hardware stores, picking up business after work, crawling into basements and attics, down holes, and through the miscellaneous rust and mildew that built up. Some nights he would go to this spot on Jefferson Avenue and dig for whatever old pieces of Detroit he could find. Beer bottles, rusted stoves. He filled the farmhouse with artifacts. He wanted to feel his fingerprints against the fingerprints of anonymous east siders from back when. The portraits of past champions above the trenches in the Cadieux consumed him. In the final weeks of the season, Gosskie began to imagine his own face on the wall. He tightened up. In the final month, his overall lead slipped to five points. Previous champions tried to keep him focused. "You don't fire at the enemy," first-class featherbowler Major Ken Withrow said, reminding him of the best path for a shot. "You fire ahead of the enemy." And that night, with the Major as his teammate, Steve Gosskie became the grand champion.

Erik Greer, a grand champion, believes in two things: featherbowling and Detroit. Andrew Cutraro

JEAN GENET ONCE SAID, "a painting by Rembrandt not only stops the time that made the subject flow into the future but makes it flow back to the remotest ages." Such is the abiding quality of the featherbowling portraits. They begin in 1987 but look for all the world as if they've hung above the trenches since the 17th century. The loose brushwork in those first portraits -- the direct stare out to the viewer, glimmer of light in the eyes of the sitter -- is directly influenced by the early Dutch masters. By the time the artist undertakes Gosskie, the pastel color palette is more evocative of Van Gogh.

Some who have seen the portraits have suggested that the open and expressive lines denote a curious sense of urgency. As if the artist is trying to capture a likeness in a short time.

The artist, Jerry Lemenu, discovered the Cadieux 37 years earlier, mourning his mother's death. He felt then as if he'd entered some surreal dream that connected the Old World to the New. If you've ever read a major daily newspaper or watched network news, you've seen Lemenu's work. He drew Pete Rose on trial. Manuel Noriega. John DeLorean. Medgar Evers' unrepentant killer, Byron De La Beckwith. Hence the urgency of the lines. In 1981, a producer for Channel 4 in Detroit was so taken with what Lemenu could see in the courtroom that he assigned him to draw the Thomas Hearns-Sugar Ray Leonard fight at Caesars Palace. Before it happened. The station gave him a box of videotapes and a computer prediction and instructions to draw every round. And for 14 rounds, one of the greatest welterweight fights in history went exactly as Lemenu had drawn it. Hearns took the early rounds, Leonard rallied in the middle. In Lemenu's sketches, Hearns comes on strong at the end but it's not enough. "I would have been right on the money except for Hearns getting knocked out in the 14th," he says.

Lemenu has won the grand championship twice -- once on the last night of the season. He also once lost it on the final night. "Everybody is a great winner," he says. "But when you can lose graciously and tip your cap like Valere Spetebroot, who would take his handkerchief out, put it down, get down on one knee and kiss the hand of the person who beat him. When you can do that kind of thing, then you get it."

Lemenu was so moved to capture Spetebroot's era, before it disappeared, he began making sketches. He read the faces of these old Belgians like the geology of the Cadieux's trenches. He did one for each new champion. At the same time, he dug back into the roots of the game, creating portraits of those who had won before he arrived at the Cadieux. Sometimes he'd have to work off photographs. "For the time I'm drawing that person, it's like they're alive again and I'm paying them another visit. That's the only way I can do it that makes any sense to me," he says. Most artists who blow through Detroit end up spitting out the same kind of drive-by ruin porn. But those who live in the city, like Lemenu, have a subtly optimistic way of looking at it. (It's why, in the end, he couldn't see the kid from Detroit getting knocked out by Leonard.) Lemenu watched Gosskie closely during that improbable championship season. "He'd throw these balls that would whack off one ball and whack off another and fall just right. Steve Gosskie was as unlikely as anybody," Lemenu says. "Maybe more than anybody, he needed it."

-

Andrew Cutraro

THE EXUBERANCE OF Gosskie's championship was sullied not long after the season ended, in the spring of 2013, when he began to feel a pain in his gut. It's kidney stones, he told himself, curled up on the floor in a ball of pain, Weezie's tail locked in terror. He finally confided to a nurse he knew that he'd been filling the toilet bowl with blood whenever he pissed. She made him go immediately to the emergency room.

He never told anybody the full extent of it. Instead, he told them what his doctor said after the first biopsy. If you spin the wheel of cancer, this is the one to get. But it was borderline stage 3. It was in the bladder. At first they told him that they'd have to remove part of it, that he'd have bags coming out of him for the rest of his life. One of the featherbowlers' wives, a doctor, ran her fingers along Gosskie's neck. Glands that should have felt like baked beans had swollen into quarters. "They won't remove your bladder," she told Gosskie, which was temporarily reassuring. Instead they began cutting out his lymph nodes. From under his arms, his abdomen, along his neck.

Lemenu colored outside the lines. He abandoned the discipline of Rembrandt for the full-blown zoomy background of Van Gogh. When featherbowlers go to a former champion's funeral, they always bring his portrait. Gosskie had been to those funerals. He drew strength from the idea that his own championship portrait would hang over what he believed was his own imminent funeral. Watching it unveiled, for the first time, on the wall above the trenches, opening night of September 2013, it completed his notion of immortality in a crumbling city. A physical capstone to a scattered life in Detroit's east side.

IN MID-DECEMBER, the portrait was stolen.

Andrew Cutraro

DETROIT WAS NEVER supposed to be a permanent stop for those Belgians who first emigrated from West Flanders. They were highly skilled tradesmen who came to Michigan to build cars. Instead, they turned their dying arts into the world's most magnificent industrial city. They did fine carpentry and elaborate brickwork. They painted the downtown's columns to look like marble. Out on the east side, they reinvented what they liked about their homeland. And they created the trenches.

Devos' father, Robert, bought the Cadieux in 1962. He soon died of pigeon-breeder's disease, a lung disorder, at which point the bar's legacy was entrusted to young Ron. Over the years, Ron would hear things that just didn't add up. Belgians, visiting the Cadieux would tell him there was no such thing as featherbowling back home.

And for years, the east side featherbowlers tried to reach out to pockets in the world where the game was said to still exist. Some made pilgrimages to Europe. They would sometimes find something called trough ballen. But the lanes they found were carpet or cement, with painted lines. There were no feathers. No ox blood. The lanes were smooth, as if they'd barely been used. What would such troughs possibly remember? One of the bowlers at the Cadieux, Big Frank, who grew up in Brussels before the war, insisted that he never heard of the game until he arrived in Detroit. Devos began to wonder: This thing we've been entrusted to protect, did we invent it?

Artist Jerry Lemenu did portraits of each of featherbowling's grand champions. Andrew Cutraro

ON NEW YEAR'S DAY 2014, Channel 2 News in Detroit aired a story about the stolen portrait. A year earlier, Gosskie had been at the height of his powers. He was always optimistic, even as the rest of the country had left his neighborhood for dead. No matter how many times the farmhouse was robbed or how often he'd get stiffed on a job, he would worship this place. In the throes of round after round of treatment, his hair had started to go. Soon he'd just have a bit of stubble where the wild eyebrows had been. His portrait was the last straw. "I was going to chemo every week. I'd get so beat up I wouldn't even answer my phone," he said.

An area code he didn't know kept showing up. Three times in an hour one afternoon. And a few hours later, there was a knock at his door. A guy named Dave Rodin had come from 25 miles downriver in Wyandotte. "I'm really sorry about what happened to your portrait," he told Gosskie, standing awkwardly on the porch. Someone at the Cadieux had given him the address. It was the middle of the lousiest winter anyone could remember. It turned out Rodin did the same grinding kind of carpentry Gosskie did. Eventually he got up the nerve and said, "I have something for you. It won't make up for your portrait being stolen."

The face was longer, more like a Renaissance painter would do it. And the black stovepipe looked like something the Mad Hatter wore. The perfection is in the imperfections. Rodin had recreated Gosskie's portrait in a pencil drawing after seeing the portrait broadcast on the Fox 2 report. Greer invited Rodin to the Cadieux that next Thursday. They honored him like a lost brother. He'd been going through his own tough times. By the end of the night, someone had offered him a job painting houses. "Of course his name was Rodin," Greer said.

-

Andrew Cutraro

THERE WERE COUNTLESS ways Lemenu could have approached his second portrait of Gosskie, who seemed to have aged a decade in the intervening year, eternally waiting for oncologists to read the lines in the next CAT scan. In the end, Lemenu conjured the howling Nash Rambler in the stovepipe hat that nobody could catch up to the night he won the featherbowling grand championship. Lemenu created a portrait so similar to the first that most people were hard pressed to see a difference. Maybe that was what his friend Steve needed to see. Maybe it was the trenches that needed this exact icon to hang over top. Maybe Lemenu just needed to exist one last time in that night Steve clinched the title, before any of them knew the twist that was coming.

A few weeks before the 2014 season opener, when the new portrait would be revealed, things had actually started to look up for Gosskie. The staff at the cancer clinic told him he was the healthiest sick person they knew, before sticking him for another bag of expensive poison. Greer, and some of the other featherbowlers, had begun dropping by to help fix up the farmhouse. They'd spin vinyl. It was starting to feel like old times. As far as anybody knew, the cancer hadn't progressed, the treatments were working. They had seen Gosskie beat featherbowling; why couldn't he beat this too?

He would tell everybody there was nothing to worry about. "They take this thing, and they zap zap zap. I get there at 1; they're pushing me out the door at 2." But before the new portrait was unveiled, it first hung quietly over him from a wall in a hospital room as new tumors dug vessels through his brain and organs and the remaining lymph nodes.

Gosskie always liked to say that if there were some kind of apocalypse, and he were the only one who survived, he'd go out to Greenfield Village, which was Henry Ford's notion of an ideal American town. Almost 20 years ago, Gosskie signed up to be an assistant village blacksmith, before he broke his shoulder tumbling over the front of a scooter at 50 mph on I-94. He returns to the village every September for the Old Car Festival. An old car show in the first city that mass-produced cars is not like an old car show in other places. They're hauled in from all over Michigan and the rest of America, even shipped by boat from overseas, not one of them built before 1933. It's the same week the featherbowling season starts back up. It's pretty much the Gosskiest weekend of the year.

Everybody who shows up at Greenfield Village is dressed like someone straight out of Gatsby -- and not the dandies from East Egg. There are penny-farthing bikes, steam cars, 19th-century electric cars, enormous Dodge tow trucks and the first Cadillacs, plus the Model B's and F's -- all the alphabet Ford used up before getting to T. Gosskie walked past a big Port Huron engine. "I know a garage in Detroit where there's one just like it, rotting away." He wiped his head with a white towel, in the manner of a mechanic wiping an engine off his hands. He'd left that stupid Tupperware container with all the little pain pills somewhere. His cellphone rang. A flip phone. "A carnival," he shouted, as a 1912 Stanley Steamer honked behind him. "We're choking on antique car fumes, man!" The sun had almost disappeared. For the first time that September, there was a chill in the air. He seemed impossibly light, as if he could just float away. He fumbled in his jacket. Where's that pill? He tried to suck in his gut, further and further, grabbing absent-mindedly at his pockets. It felt as if he was drying up from the inside.

Earlier that afternoon, one of the other bowlers had given him a box of green peppers and kale. Super food. "Dude, I'm doing way better," Gosskie said. He had pounded three Red Bulls to jack himself up for opening night. "I'm not drinking anymore. I need to get that buzz going somehow," he shrugged.

"How'd you do?"

"Oh man, we lost."

"How many points?"

"Three."

They both cringed. Gosskie's old man came to watch that night. "First time he'd ever been there [for a match]," Gosskie told his friend. They said nothing for a while, looking down into the kale. He shrugged again and said, "I guess he got to see what the guys thought of me."

"The perfection of our game is in the imperfection of the lanes," Greer likes to say. Andrew Cutraro

THAT NEXT THURSDAY after the car show, teamed up with Devos, Gosskie won handily. Greer noted how well Steve bowled. The week after that, he went in for another surgery. And the next week, he was driving out on 8 Mile. It was Weezie who saw it. She usually sits in the backseat, but she'd jumped into the front. Unsettled, she stuck her nose in between his armpit and elbow. Turn around, let me see you. The muscles tightened up in his arm and jaw. He pulled off the road. He wouldn't hide the result of his next CAT scan. "It's all over my brain," he would tell them the next time he came to the Cadieux. Stage 4. Terminal.

It's easy to dismiss it all as dumb luck, the way the wheel breaks up and down the sides of the trench, around that perfectly set sentry in the middle, seeming almost to suck in its gut as it squiggles between two more guards, before trundling way up the other side of the trench, and down like a Grumman Goblin through the next melee, then up and down a third time, and a fourth time, sometimes a fifth, before it turns into this wounded forest creature, twisting unnaturally as it knocks against several balls in a single movement, down into this death rattle that makes all the people standing along the trench hold their breath and get up on their toes and bite down hard on their lip and fall down to their knees, and scream. Down goes Frazier.

Stage 4 terminal is that last up-and-down. It's the shortest distance, but the time in which everything happens. You featherbowl, year after year, just to feel that latent energy suddenly erupt. Gosskie said his brain looked as if it was covered with fingerprints. "It's turning me into a f---ing savant, though, dude," he said, late one night. "My recall is so sharp right now. I feel like I can play a grand piano. I'm building this whole thing, this bundle together, the farmhouse and the stage, and these other houses. You should see my little notebook."

By the end of October, he had made an asshole list and a friend list and sketches and secret plans. One of the featherbowlers had opened a bicycle factory, and Gosskie was designing a model called the Ambassador. He was building a new feather bowling trophy. "But don't tell anybody that yet." He was up at all hours. It all came together in this much larger vision. The pieces of that scattered life would be rebuilt, in one big deal that would turn the area around, the Cadieux into his own Greenfield Village. The Farmhouse and the old studio across the street. Devos' bar would be the focal point. There were three houses for sale -- the early-20th-century ones you'd order out of the Sears Roebuck catalogue -- this is where the glassblowers and blacksmiths, anybody who did the old arts, would work. He always liked to remind people that that old east side was only six hours by horse and buggy from downtown. "I've got a lot of plates in the air," he said, then abruptly stopped. "You know what time it is now? It's 12:12; that's three three. Dude, I stopped smoking at 12:36 last night." Half a beat passed. "All divisible by three."

They say about America that if you love a patch of it hard enough, you begin to remake it in your own image. In the end, it's the godforsaken patches we protect the hardest. However far down that dirt goes into Detroit's east side, something farther beneath the surface pulls a wooden ball one way, and something else near where the portraits hang under the pressed tin ceiling pulls a shot another way.

A week and a half after Gosskie died, 3:07 on the afternoon of Nov. 22, the featherbowlers gathered around the first trench at the Cadieux and carried out what some had come to call the rolling of the last ball. Some stepped forward, their normally strong voices timid, as they shared a final memory. Michael Chateau had stayed up late the night before memorizing the lyrics to "Blue, Red and Grey," which he sang, unaccompanied, beneath Steve's portrait. On a silent cue, arms stretched out with tins and bottles in each hand, like an arch of sabers on a rusting battleship in some remote sea, the last ball rolled 60 feet through the dirt, where Marc Tirikian waited to catch it, and they felt everything that death takes. And the one thing it cannot.

Erik Greer would go on to win the grand championship, regaining the preternatural form that had eluded him since those early weeks of Gosskie's miracle run. Greer always suspected that Steve had been understating his prognosis. He and Tirikian and a few of the other bowlers had quietly put about $1,000 into a little fund. They formed a steering committee and met to figure out how to execute whatever the hell Steve was scheming. That October, they had rented a 30-yard dumpster, told everyone they knew to bring work gloves and square-ended shovels and help dig into the pile of mortar and brick that some jackass had dumped behind the farmhouse. It seemed futile and impossible. Steve was always wrenching something from itself with no clear end. Nobody had any idea what they were even building. Like the old Belgians digging those strange trenches out during the Depression, it just made perfect f---ing sense.

of

Illustration by Martin Laksman

Illustration by Martin Laksman