Baseball will be buzzing Thursday when Matt Harvey pitches in a regular-season game for the first time in nearly 20 months, following Tommy John surgery. Harvey, who has been stellar this spring, has been a source of optimism for a New York Mets fan base that can't wait to see what he can deliver.

Harvey will face the Washington Nationals, led by Stephen Strasburg, a 2010 graduate of the ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction and rehab program. So far both pitchers appear to be fine examples of the success of the procedure, which has saved many pitching careers since it was first performed on Tommy John in 1974.

But what about Harvey's teammate, Jeremy Hefner? He had Tommy John surgery two months before Harvey, but then re-tore his ligament and underwent a second surgery in 2014.

Or Cory Luebke? He had Tommy John surgery in 2012. After enduring multiple setbacks in his recovery, he underwent his second Tommy John surgery in 2014.

Or Joey Devine? It took him two years to return from Tommy John surgery in 2009 -- only to suffer re-injury in 2012 followed by a second surgery. He hasn't pitched since.

No one talks about them. Maybe it's time we did.

"You hear about guys who do well," said Dr. Chris Ahmad, the New York Yankees' team physician and the author of several studies relating to Tommy John surgery. "The guys who don't come back tend to fall out of the conversation."

The incredible success of some of MLB's most celebrated pitchers following Tommy John surgery has helped perpetuate three prevailing myths:

Everyone has a successful outcome.

The surgery improves performance. And perhaps the most troubling of all:

Young players should proactively seek Tommy John surgery to "prevent" a future problem and "enhance" performance.

There is no doubt that awareness of the frequency of elbow ligament injuries has been elevated. In 2014, the attention-grabbing number of players undergoing Tommy John surgery -- and, perhaps more significantly, the star power names involved in recent years -- sounded an alarm in baseball that maybe this injury was spiraling out of control. The injury (tearing of the ulnar collateral ligament), the surgery (using a tendon graft to reconstruct the UCL) and the rehabilitation process are now familiar. Yet the problem persists. Are we missing something by lumping everyone who sustains the injury into one collective Tommy John surgery pile? A closer look at the data suggests we are.

Tommy John surgeries among MLB players, 1999-2014

The blue lines indicate the total number of surgeries, while the red lines show the number of revision surgeries, including a record 11 in 2014.

The revision epidemic

At first glance, the total number of Tommy John surgeries among MLB players (31, 30 of them pitchers) jumps off the page in comparison to previous years. (Over the past 15 years, only 2012 had more: 36.) But there's another fact that should command more of our attention: 11 of the 31 surgeries in 2014 were revisions, or repeat Tommy John procedures. In other words, 35.5 percent of pitchers having Tommy John surgery in 2014 had previously undergone the procedure. The initial graft subsequently failed, and they were now undergoing yet another UCL reconstruction. For one of the revision pitchers, Jonny Venters, it was his third such procedure.

Much of the research on revisions has been done by Stan Conte, vice president of medical services for the Los Angeles Dodgers. After spending countless hours studying data related to Tommy John surgeries -- both primary and revisions -- the number that grabbed Conte's attention was the spike in revisions over the past three years.

"We've seen as many revisions from 2012 through 2014 as we had in the entire prior decade," Conte said.

Since 1999, of the 235 MLB pitchers who have undergone Tommy John surgery, only 32 have undergone revision -- but one-third of them have occurred in the past year. In 2015, one MLB pitcher (Joel Hanrahan) has already undergone a revision surgery.

Why are revision surgeries skyrocketing? No one knows for sure, but here are a few theories.

Revisions were scarce initially because even a first Tommy John procedure was relatively rare. The frequency of Tommy John surgery over the last decade has increased the potential revision pool. Although 1974 was the year of the original surgery on Tommy John, the number of such surgeries performed in a year did not reach double digits until 2000.

Perhaps personal success following the first procedure leads players to think it's worth repeating. Now that more pitchers have had Tommy John surgery and subsequently returned to competition, more might be inclined to do it again. After all, if they believe they were able to return to their previous level of performance (or close to it) and feel there's plenty of life left in their arms, why opt for early retirement? Even if they anticipate returning to a lesser role, they may believe it's worthwhile.

By the time a pitcher arrives in professional baseball, the wear and tear on his elbow might be significantly greater than it once was, making him more at risk for Tommy John surgery early in his career -- and consequently, more at risk of needing a revision.

Tommy John surgeries by MLB team

The Atlanta Braves and the Chicago White Sox ended up at opposite ends of the surgery spectrum.

Top five

Bottom five

In the past decade there have been pitchers entering the First-Year Player Draft who have already undergone Tommy John surgery. In 2014, two pitchers -- Jeff Hoffman and Erick Fedde -- were drafted in the first round despite already having had Tommy John surgery. Brady Aiken, last year's No. 1 overall pick, had the procedure done on March 25. Duke right-hander Michael Matuella, considered the No. 1 college pitching prospect for 2015, was just diagnosed with a torn UCL that will require surgery. Others, like Pirates prospect Jameson Taillon, the No. 2 pick in 2010, had the surgery while in the minor leagues. If these pitchers ever progress to the majors, they may be more at risk for a second injury over time.

The recent willingness of pitchers to undergo revision surgery is interesting, given that revisions reportedly have been reported as being less successful than first-time Tommy John procedures. After all, revisions may require additional drilling in the bone to accommodate the second graft; the surrounding tissue may be deteriorating from repetitive throwing; and the pitcher is, well, aging.

One study published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine in 2008 (Dines et al) focused on revision outcomes in baseball players and found 33 percent returned to their previous level of competition for at least one season. The study was limited to a small sample size (15); 12 were professionals but only four were MLB players. When compared to the success rates for first-time Tommy John surgeries, frequently reported in the range of 80-85 percent, the idea of undergoing revision surgery has been less appealing historically, especially for an athlete who might be approaching the later stages of his career.

But does that accurately describe a player seeking a revision? Maybe not. Of the 11 MLB pitchers who underwent repeat procedures in 2014, more than one-third of them (45 percent) were less than three years removed from their original surgery. Considering the rehab process following Tommy John surgery ranges from 12-18 months, it would suggest this subset of pitchers had not been back at performance level for more than a year (and in several cases never returned to their previous level of performance) before requiring a second surgery.

While it is logical to expect a graft to be weaker and less durable than the native ligament and prone to failing over time, the typical revision candidate in the past has been the older athlete, following more than five years of pitching off the original reconstruction (like Brian Wilson and Joakim Soria). But recently, several younger, sooner-to-failure candidates have emerged. There is no definitive explanation, and no blame to be assigned. But the observation is worth noting if we are to learn more about why this phenomenon is occurring.

Before and after

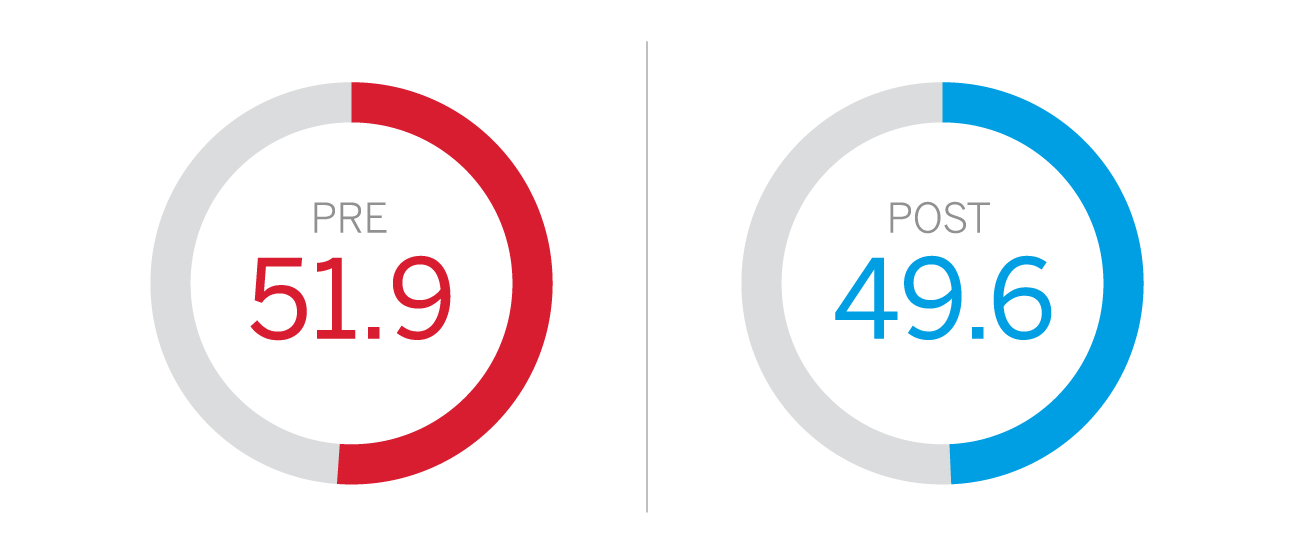

Average fastball velocity (mph) for five starting pitchers and five relief pitchers who had Tommy John surgery:

Starting pitchers

Relief pitchers

Not a performance-enhancing procedure

While the recent growth in revision numbers is most striking, the number of primary TJ surgeries has remained elevated over the past decade, and more so in the past three years.

Unfortunately, the general perception that the injury is unavoidable, particularly among hard throwers, has many believing in a proactive approach to surgery. In a 2012 study published in The Physician and Sportsmedicine journal (Ahmad CS et al), surveys were conducted of high school and collegiate players, coaches and parents to evaluate their perceptions of Tommy John surgery. Among the respondents, 28 percent of players and 20 percent of coaches believed performance would be enhanced beyond pre-injury levels after undergoing Tommy John surgery. Perhaps most alarming was the finding that 30 percent of coaches and 37 percent of parents thought surgery should be performed on players without elbow injury to enhance performance.

The idea that Tommy John surgery improves performance is misguided based on the success rates and performance metrics following the procedure. In medical literature, returning to the same or higher level of competition has long been the measure of documenting success when it comes to athletic injury recovery. In baseball medicine, a major league player returning to competition at the major league level following Tommy John surgery -- even for a single outing -- has been the standard definition of success.

But when a pitcher undergoes significant reconstructive surgery, followed by a rehab process that lasts for a year or longer, it's hard to believe his definition of success would be one outing.

The authors of a 2014 study published in the American Journal of Sports Medicine described a different metric for a successful return following Tommy John surgery. In an article titled, "Performance, Return to Competition and Reinjury After Tommy John Surgery in Major League Baseball Pitchers," the authors (Makhni EC et al) reviewed 147 cases of MLB pitchers who underwent Tommy John surgery between 1999 and 2011. They defined players who returned for at least one game post-operatively as "active," but those who appeared in at least 10 games in a single season post-operatively were considered "established." The pre- versus post-operative performance of established pitchers was examined and their performance was also compared to age-matched pitchers in a control group.

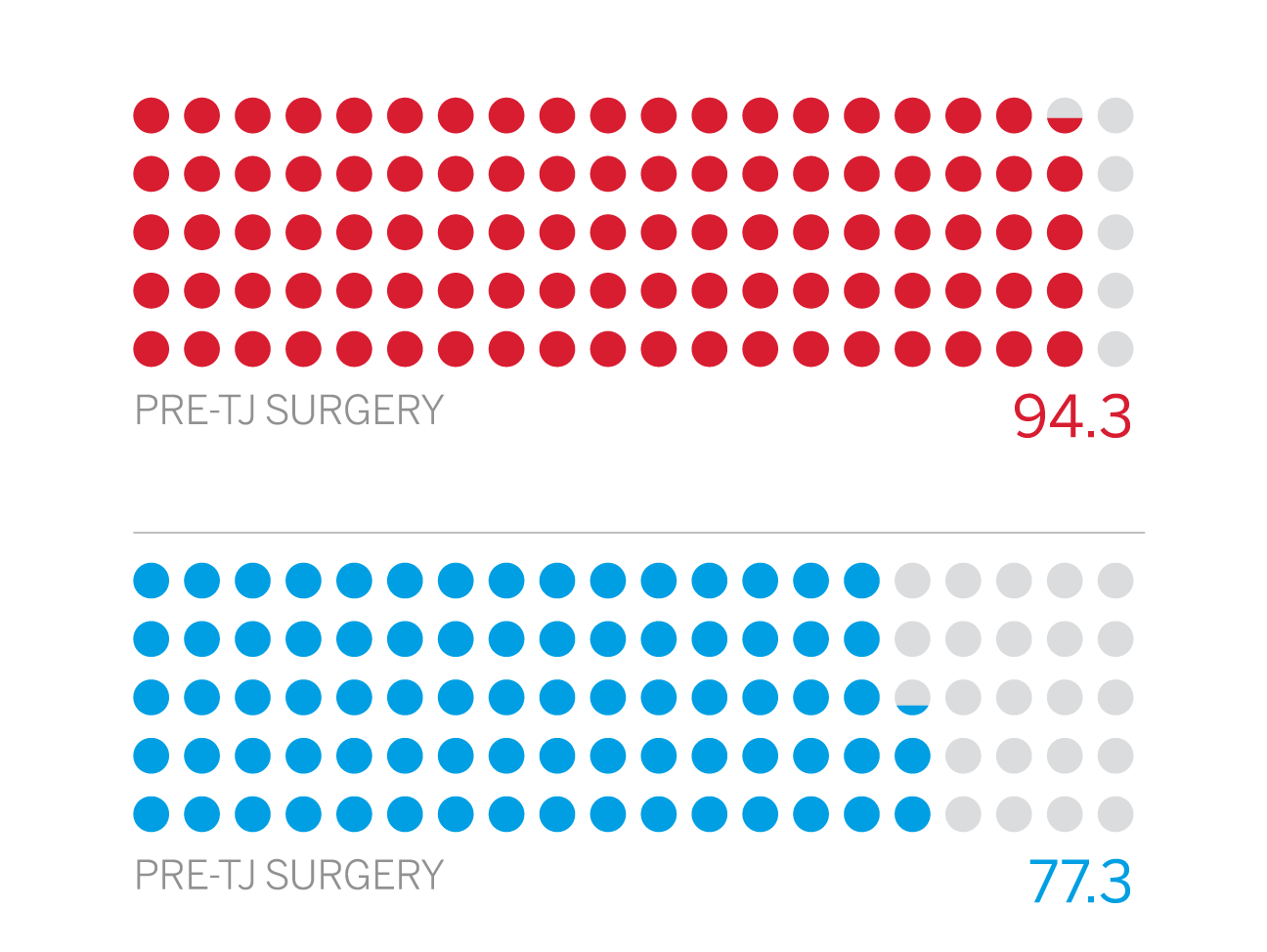

Breakdown of MLB pitchers having Tommy John surgery, 1999-July 2011

Upon their return from surgery, two-thirds pitched in at least 10 games or more in a single season at the major league level. The remaining one-third did not.

Several findings are particularly noteworthy:

Of the 147 pitchers included in the study, 80 percent returned to pitch in at least one game ("active"). This is fairly consistent with the success rate following TJ surgery that has been previously described. But when the criteria shifts to at least 10 games in a season ("established"), the success rate drops to 67 percent.

More than 50 percent of players returned to the disabled list after their return from TJ surgery with an injury to their throwing arm.

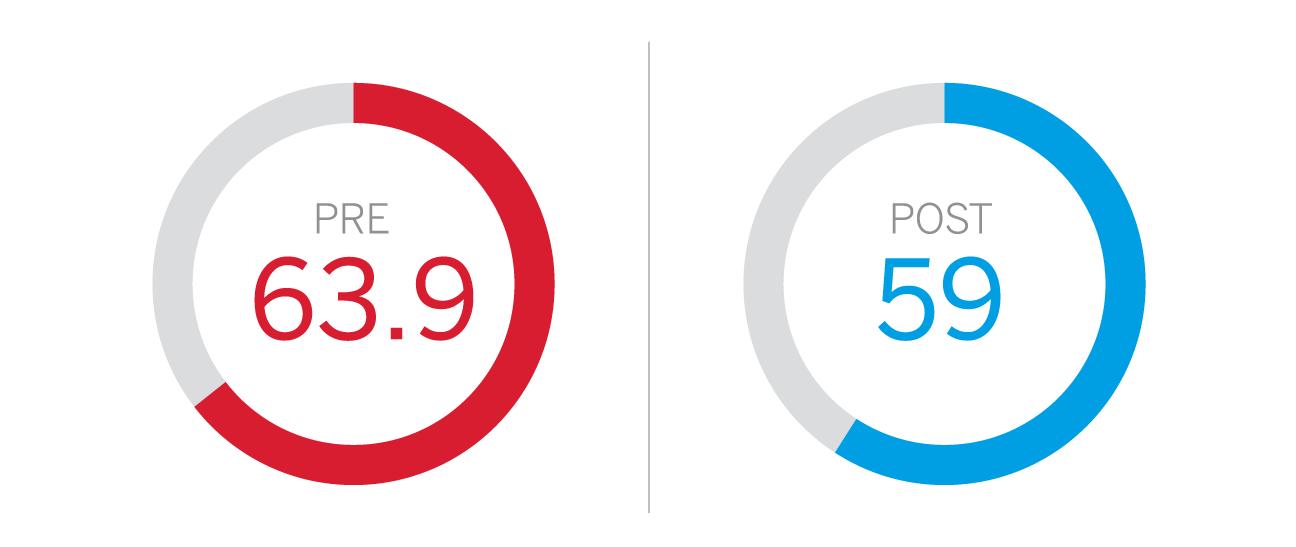

Performance metrics for established pitchers post-injury showed a decline when compared to pre-injury numbers in each of the following areas: ERA, batting average against (BAA), walks plus hits per innings pitched (WHIP), percentage of pitches thrown in the strike zone, innings pitched, percentage fastballs thrown and average fastball velocity.

The performance declines noted above were not statistically different from declines in age-matched control groups that had not undergone Tommy John surgery.

At the very least, the results challenge us to think differently about what signifies a successful return following Tommy John surgery. The findings may also encourage more thoughtful consideration when weighing treatment options following a lesser injury -- such as a partial thickness ligament tear (Masahiro Tanaka's elbow, for example) -- that does not mandate surgery. In the presence of a failed UCL that prevents an athlete from participating in baseball, however, surgery remains a solid option.

What is baseball doing about the preventing elbow injuries that lead to Tommy John surgery?

For better ... or worse?

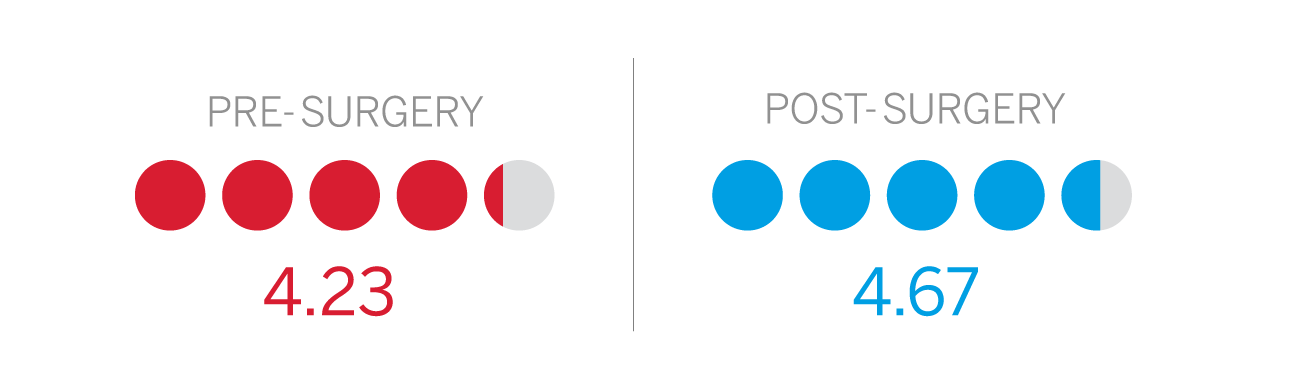

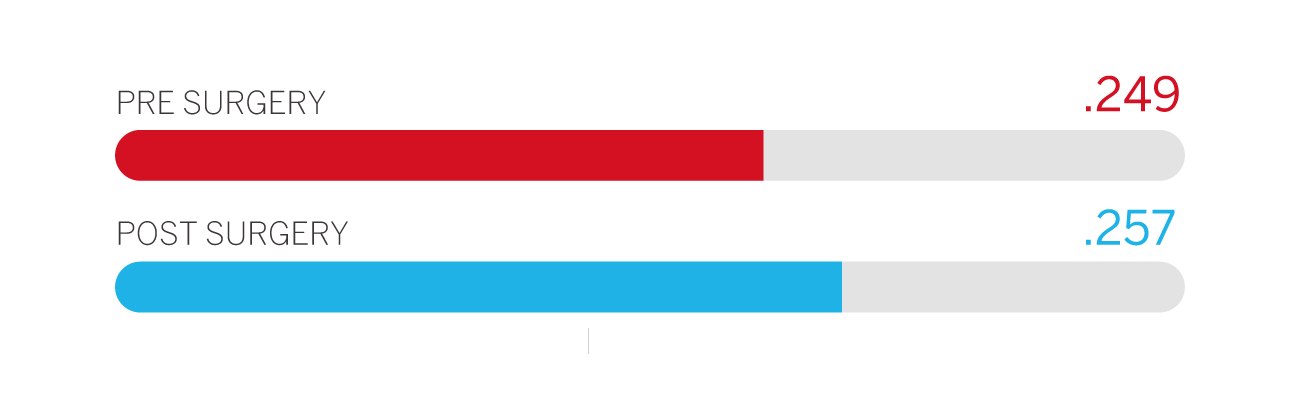

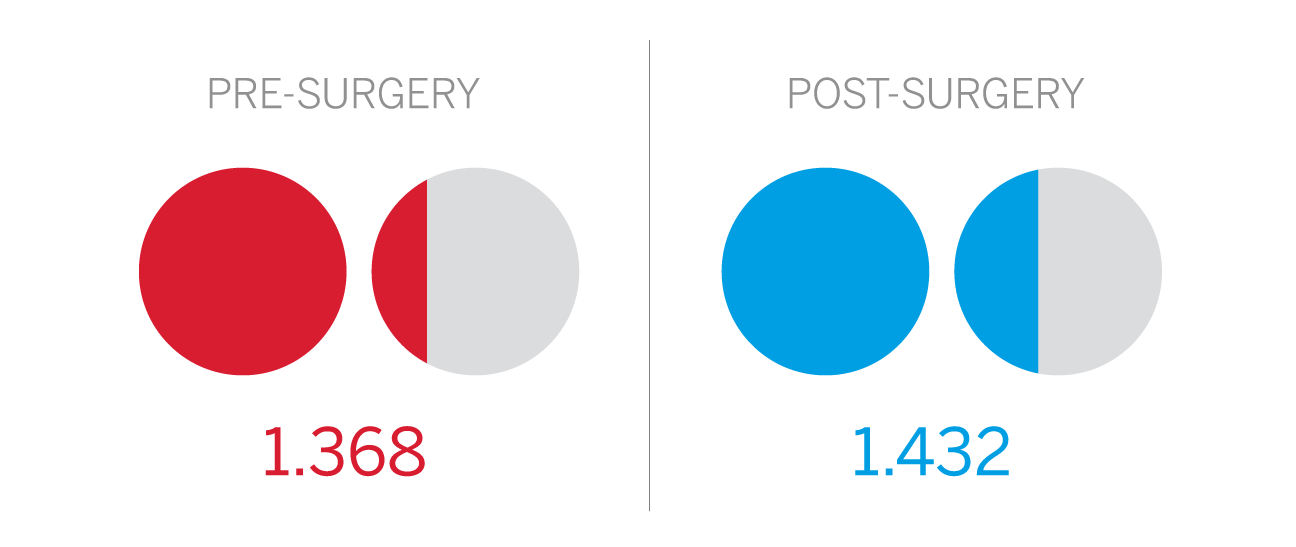

Comparing pitching performance before surgery with performance after returning shows a statistically significant decline in the following performance metrics (maximum 3 years before and after)

ERA

BAA

WHIP

% of pitches in strike zone

Innings pitched

% of fastballs thrown

Avg. fastball velocity (mph)

Education at the youth level

Educating those involved with youth baseball is critical in order to stem the tide of injuries. Not only does it make sense to keep kids healthy so they can remain active, it also has the potential to enhance the available talent pool for the pros. Kids who give up baseball due to injury or burnout (or both) might have been really talented collegiate or professional players had they lasted in the sport.

To aid in the education effort, MLB launched the PitchSmart website in 2014. Developed in conjunction with an advisory committee comprised of baseball medicine professionals, the site serves as a resource for parents, coaches and young athletes. It offers pitching guidelines, answers to frequently asked questions about TJ surgery, research links and videos.

Most innings pitched following Tommy John surgery (all active pitchers)

Pirates right-hander A.J. Burnett had his elbow surgically repaired by Dr. James Andrews on April 29, 2003. Now 38, Burnett is still going strong as he begins his 16th and final MLB season.

Using data to prevent injury

Education around the surgery is only as good as the information being delivered. While data has been published in recent medical journals related to performance metrics and return rates following Tommy John surgery, no comprehensive study has looked at all the potential risk factors for ulnar collateral ligament injury -- until now.

MLB has directed research dollars toward a five-year prospective study that will follow players from the time they are drafted in an attempt to better understand why this injury happens and who might be most at risk. Some of the variables to be examined include previous medical and pitching histories, physical examination and imaging such as MRIs (taken within the first year of professional baseball) and biomechanical and range of motion metrics. Pitching volume, types of pitches, pitch velocity and other pitching metrics will be monitored over the five-year timeframe. By carefully tracking data, the hope is that correlations between suspected risk factors and injury will emerge and help guide future injury prevention. Other groups are trying to find answers as well.

The MThrow sleeve utilizes a sensor worn in the sleeve to capture data such as torque, velocity and workloads. The data is then transmitted via Bluetooth to a mobile app for analysis of metrics related to pitching performance. Following a pilot program involving nine MLB organizations during the Fall Instructional League, the sleeve was recently granted approval for in-game use during the regular season. The idea is that the 3D data will help teams monitor player workloads and spot changes in mechanics in real time.

Along similar lines, Kitman Labs recently signed an agreement with the Dodgers to track and analyze biometric data and player performance. Kitman has had success in Europe with soccer and rugby players in lowering injury rates; the hope is that the program will do the same for baseball players.

It's an odd phenomenon when a surgical procedure, along with its ensuing rehab, is perceived as a fail-safe mechanism for the original injury. It has happened with the anterior cruciate ligament in the knee, and it's happening now with the UCL in the elbow.

The rising numbers of Tommy John surgeries, particularly revisions, and the shifting demographics (younger players, both at the amateur and professional levels) suggest a problem that is more complex than it initially appeared. As Conte said, "Now that we've identified layers to this problem, we need to find the actual causes."

Hopefully, when the next generation of Harveys and Strasburgs are facing each other, the story will be about how rare Tommy John surgery has become among young pitchers.