This is part of a seven-story package assessing the state of the young NFL quarterback. Look for more on Jameis Winston, Marcus Mariota, Johnny Manziel, Andrew Luck, Andy Dalton, Cam Newton and others in ESPN The Magazine's How to Raise a QB Issue, on newsstands Nov. 13. Subscribe today!

LOOK AT CAM NEWTON'S hands. They are capable of making a football all but disappear. At 9 7/8 inches across, they give Newton license to do things no other quarterback would even try. Facing the Eagles in late October, on second-and-goal from the 2, Newton runs a quarterback draw out of the shotgun. He seemingly is stopped for no gain, but with the ball secure in his right hand, he twists and stretches and, with one last burst, extends his arm toward the goal line, the most vulnerable position a player can be in. Just then, Newton is hit squarely in the back, a lick that would jar the ball free from 31 other quarterbacks -- hell, most ball carriers. But not with these mitts. Instead of fumbling, Newton reaches the ball over the plane for a touchdown, making it look easy. They're blessings, these hands. Ken Dorsey, quarterbacks coach for the Panthers, believes they enable Newton to put more rpm on the ball than other passers. And they have helped Newton become the force that many predicted when the Panthers picked him first overall out of Auburn five years ago. But they could have been a curse. Because someone with those hands might have been tempted to fall back on his physical gifts without putting in the work required to be a truly great quarterback.

LOOK AROUND THE league. Quarterbacking appears to be an old man's game. By now, we know that nobody has a clue how to project the future of college quarterbacks entering the NFL, and we know that the ability to master the complexity and nuance and pressure of the position eventually distinguishes the greats from everyone else. But we really don't know a lot about the years in between, the formative years, the ones quarterbacks spend with question marks over their heads, when they either separate themselves or don't, when they take a raw mix of doubt and talent and will try to earn what Steve Young calls "a master's in football." There is no one class, no easy road map. Each quarterback is as unique as his skill set.

Three star quarterbacks in their fifth years -- Andy Dalton, Colin Kaepernick and Cam Newton -- all appear to have reached turning points this season. All have endured their share of question marks and been burdened by different narratives. Dalton: the pocket guy who, in fits and starts, seems now to be figuring it all out but still must prove himself in the playoffs. Kap: once thought to be the future of the NFL but now a backup. Newton: the guy with the potential to be the game's most dangerous player. But these narratives obscure the most fundamental truth about trying to become a great NFL quarterback: It's a messy and mundane and insanely frustrating process, and the payoffs from one's labors don't necessarily appear all at once. You just hope they do so before it's too late.

"F --- YOU, ANDY!"

It's hard to tell whether Andy Dalton hears the Bills fan yelling at him. Dalton is smiling as he runs off the field at Ralph Wilson Stadium after swapping jerseys with Buffalo defensive end Jerry Hughes, his old teammate at TCU. For the past three hours, in a perfect Buffalo mix of snow, rain and sunshine, Dalton tore apart the Bills, throwing for three touchdowns, avoiding every sack attempt, reading Rex Ryan's defense fluently. The 34-21 win in Week 6 kept the Bengals undefeated -- they are now 8 -- 0 -- and solidified Dalton's place in the MVP race. The performance furthered a conventional wisdom forming around the league: that Dalton, after four straight seasons of playoff one-and-outs, is suddenly different.

Of course, the word on Dalton has always been that the crucial moments are too big for him. Clutch is innate, not learned, most scouts believe. And so when it came time before last season to redo his contract, the Bengals signed Dalton to what grabbed headlines as a six-year, $115 million contract but in reality was a two-year, $25 million deal that allows the team to cut bait after this season. A few months ago, some Bengals fans were counting down the days. When Dalton jogged onto the field in July for major league baseball's All-Star celebrity softball game in Cincinnati, the hometown fans booed him. That dour welcome, so the story goes, has served as motivation this season, the clichéd chip on Dalton's shoulder that has led to 18 touchdown passes and four interceptions. Dalton calls the booing "unfortunate" because "it's not like we've had losing seasons. Yes, we haven't won in the playoffs. We get it."

But he doesn't see a dramatic change in his play so much as the natural result of years of grinding. This past offseason, Dalton worked with Tom House, one of a handful of renowned quarterback specialists, for three weeks. He says House and his colleague Adam Dedeaux helped tighten his throwing motion. It's helped him be more decisive: His average time before throwing is 2.20 seconds, second only to Tom Brady's 2.13. All of that matters more than being inspired by boos. And being in offensive coordinator Hue Jackson's system for a second straight year has allowed Dalton to switch from being left-brained -- just trying to remember the language and progressions of the offense -- to being right-brained, creating and anticipating holes in the defense rather than hoping to find them. Says Dolphins offensive consultant Al Saunders, who worked with the Bengals this past offseason, "It's like moving into a new neighborhood: First you learn how to go home, and then you realize what's around you."

It doesn't mean Dalton has arrived. It means he has improved in ways invisible except to himself, tiny measures of success. Dalton started running offensive meetings this year, elevating himself to the Brady/Manning player-coach level. Jackson says that Dalton is now "winning games with his mind" and estimates that 25 plays a game -- about 40 percent -- are audibles. Some of Dalton's proudest moments from this season aren't the obvious highlights but the hidden ones, such as checking from a pass to a run that resulted in running back Giovani Bernard's 17-yard touchdown in the second quarter against the Bills.

But development isn't linear: Late in the first half in Week 5 against the Seahawks, Dalton threw an interception to safety Earl Thomas. At halftime, Jackson had never seen Dalton so angry with himself, and he wondered whether his quarterback would struggle to flush the bad play -- just like in those playoff losses -- and regress. Dalton's on-field demeanor was one of his main focuses with House and Dedeaux, and while House won't discuss specifics -- citing the quarterback version of doctor-patient privilege -- he says the main area of "significant progress" for Dalton this year is not his throwing mechanics but his body language. Sure enough, this time Dalton unspun himself quickly. "He had clear eyes, and we had clear conversation," Jackson says. With the Bengals down 24-7 in the fourth quarter, Dalton rallied them to a 27-24 overtime win. But the storyline has lingered: Is he different? "I wouldn't say there are things I'm doing now that I wouldn't have done a year ago," Dalton says. "A lot of people say, 'What's different? What's new?' It's not new. I've had success since I've been playing. I wouldn't say there's a huge evolution." Just a culmination of many small ones.

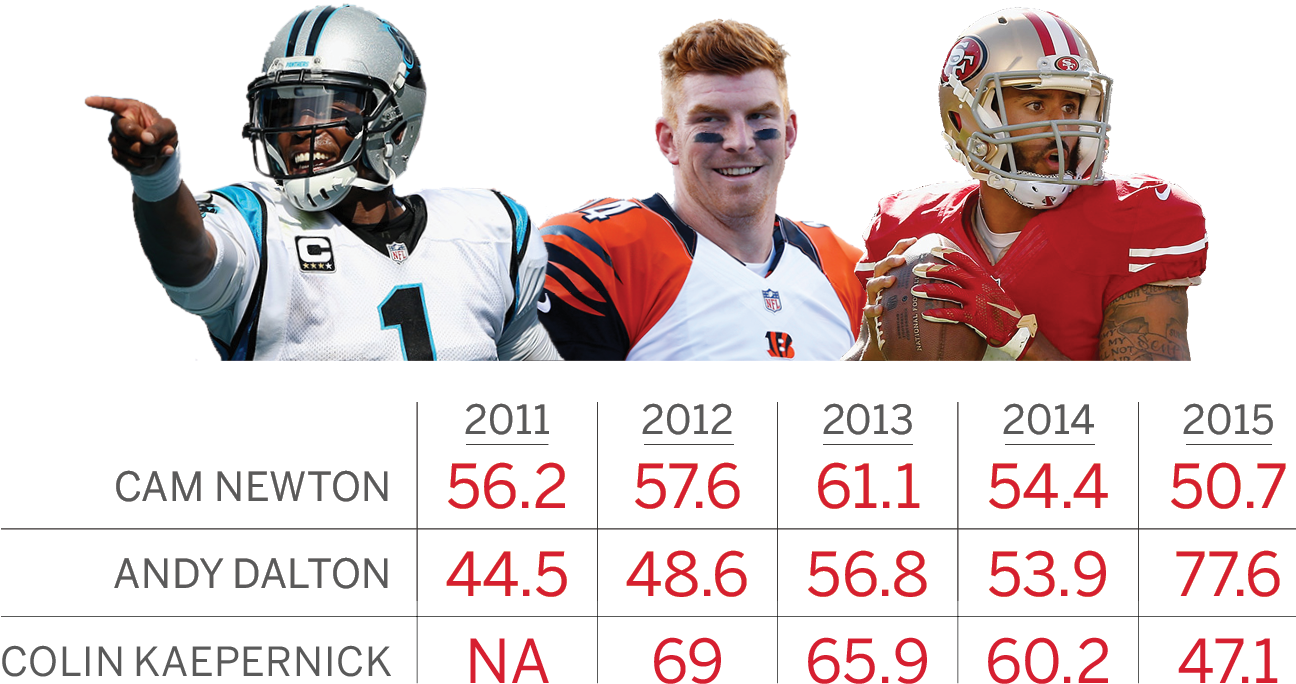

QBR over first five seasons

SLIDING INTO A booth at a Scottsdale breakfast spot one morning in October, Kurt Warner is about to try to answer a question that has vexed everyone, inside and outside the 49ers' locker room: What the hell happened to Colin Kaepernick?

Not long ago, with a slingshot arm and a deerlike stride, Kap seemed to be football's future. He had beaten Brady in Foxborough, Drew Brees in New Orleans, Matt Ryan in Atlanta, Newton in Carolina and Aaron Rodgers twice in the playoffs. Ron Jaworski predicted he could be the greatest ever. He was the ultimate sandlot quarterback, led by the ultimate sandlot coach in Jim Harbaugh. But the cracks in his performance that began to form last year, hidden by the drama surrounding Harbaugh's job status, are fixed in sharp relief now that the coach is gone. Kap has become a football version of Chuck Knoblauch, high and low and unable to execute something that once came naturally. His QBR of 47.6 is more than 20 points lower than it was in 2012, his first year starting. New coach Jim Tomsula finally benched Kap for Blaine Gabbert after Week 8, saying he wanted "Colin to step back and breathe," a move the coach hopes will serve as a reset, not a permanent solution.

This past offseason, Kap spent three days a week for six weeks in Phoenix under the tutelage of Warner. Unlike the other quarterback gurus, Warner is one of the few who perfected the craft himself. He possessed the rare mix of quickness, accuracy, heart, brains, work ethic and ruthlessness to become a Hall of Fame -- worthy passer. His unlikely story -- from stocking shelves in a grocery store to winning a Super Bowl -- proved just how undetectable and unpredictable that skill set is. He made for an interesting pair with Kap, whose dazzling running has led to many kissed biceps but also allowed him to avoid learning the position traditionally. Warner's challenge was to teach Kap how he thinks in an incredibly short amount of time, knowing that only a handful of quarterbacks each generation can process the way he did. Says Warner, "I told him, 'The hardest part of this process will be that you don't think like me, and I've never been able to think like you.' When do I stop being a quarterback and become an athlete? I never had to worry about that."

Over a cranberry juice, Warner leans on the table and watches video of a play from Week 4. Fourth quarter, 49ers down 17-3 to Green Bay, trying to rally. On second-and-5 from the Packers' 15-yard line, Kaepernick takes the shotgun snap, sees running back Reggie Bush wide open over the middle for what should be a walk-in touchdown. "A layup," Warner says. Kap fires it in the dirt. Warner rewinds the clip, then freezes the frame as Kap is throwing. "The biggest thing that I see with Kap quite often -- and it's frustrating -- are his feet." As Kap releases the ball, his feet are parallel to the line of scrimmage, rather than perpendicular. He's throwing with all arm, rather than with his body. The result is a pass both late -- Bush was open by three steps before Kap even noticed -- and inaccurate. "Normally good quarterbacks don't throw like that," Warner says.

Warner leans back, disheartened. They had focused on footwork in the offseason. He was even more disheartened when Kap told reporters that he was "not huge" on mechanics. "That tells a big story right there," Warner says. He isn't faulting Kap's work ethic. "He worked his butt off" in their time together, Warner says. He is saying that Kap isn't really a fifth-year quarterback. He's a fifth-year player, 28 years old, but developmentally behind the curve. Warner faults the way football is trending, with youth and college coaches putting their best athletes at quarterback and deploying them in the spread, exactly what happened to Kap at the University of Nevada. "So now," Warner says, "we're saying -- at the highest level, against the best talent -- you have to learn how to play quarterback. To me, it sounds impossible."

As he has struggled, Kap has become a divisive force in the Bay Area. By all accounts, he's a good, funny dude, but he can be edgy and distrusting. The unyielding self-belief and loner tendencies -- eyes down, ears always enclosed by headphones -- that fueled his success and drove the 49ers to within 5 yards of a sixth Super Bowl now seem to rub people in the building the wrong way. His receivers have been visibly angry with him this season, throwing up their arms when he misfires or fails to see them open. The 49ers have tried short, quick throws to restore his confidence, but coaches can mask deficiencies for only so long. Kap is in a cruel morass, as much psychological as physiological, trying to solve problems as elementary as footwork against defenses that require a master's degree to decipher. "How long does it take to get there? Can he get there?" Warner says. "That's the crapshoot."

Warner moves on to another play, one that, on its surface, shows Kap summoning his old magic. It's against the Ravens, two weeks after the Packers game. He takes the shotgun snap and looks right, darts left as if to run, spins back right, resets and fires a 21-yard touchdown to receiver Quinton Patton, a combination of arm strength and elusiveness that only a few quarterbacks can match.

But no. Warner rewinds to the beginning. Kap sees that his first read is covered. Warner points out that his second read, Anquan Boldin, is wide open on a slant. But Kap doesn't even look his way. Instead, he panics, in a clean pocket. "His feet go haywire," Warner says. "There was no pressure." And when Kap throws, his feet are in the same position as they were on the misfire to Bush. It raises more questions than it answers. Can you live with the pass in the dirt knowing that the same mechanics will produce spectacular plays? Can he still be the 49ers' franchise quarterback -- or will it happen elsewhere, with a fresh start, if it happens at all? Like the 49ers, Warner seems resigned. He stares at Kap's feet, parallel to the line of scrimmage, play after play, and imagines trying to beat NFL defenses from a position of weakness.

"It's hard to live in that world," he says.

CAM NEWTON KNOWS his hands are weapons. He can dribble a football behind his back and between his legs, and he thinks he should be on the Panthers' hands team. In the game against the Eagles, on one play Newton is bouncing in the pocket when a rusher comes flying at him and knocks the ball out of his right hand. But in a split second, almost too fast to believe, Newton catches the ball with his left, transfers it back to his right and fires a strike downfield. It's the type of play only he can make.

The thing is, the most important thing Newton does with his right hand is write in his notebooks. He updates them meticulously, head down in meetings, scribbling each day, his notes ranging from keys to the defense to reminders to be patient and take what the coverage gives him. These notes don't just reveal why he has been so successful. They could be the key to answering a long-running question: When will a true dual-threat quarterback dominate the league?

Almost every year since Michael Vick was drafted, a different quarterback has been expected to revolutionize football. Turns out, none of them has. Turns out, pocket passers still own the league, which explains why the best quarterbacks are the most seasoned ones, able to read defenses quickly because they've seen them all. Young, for one, has wondered when the first true triple threat -- a quarterback who can run, throw and process from the pocket, and all at a Hall of Fame level -- will arrive. He has challenged young quarterbacks to put in the classroom work, to embrace the mundane process of turning chalkboard theories into "reflexive recall." It's the boring side of greatness, three or four years of studying in pursuit of an advanced degree. But as Young often laments, it's hard to persuade guys to do it after they've achieved rapid success. The will to be truly great is more elusive than the skill set.

Newton, with his athleticism and smarts, isn't a true triple threat -- yet. The phrase that teammates use most often to describe Newton is "in command." Most of his runs -- he averages 5.4 yards a rush and has scored 37 touchdowns in his career -- are designed. When he throws, he usually does so from the pocket, negating the narrative of a running quarterback. Many of his best plays from this season have come when he hangs in the pocket and squeezes the ball into the arms of one of his receivers, who are among the worst in the league. Against the Seahawks in October, Newton dropped back and looked left. His first three options were covered. He turned back right, held his feet as the rush closed in and laced a ball between two defenders to tight end Greg Olsen for 32 yards. "It was a full-field read," says Dorsey, the Panthers quarterback coach. "He's really good at making smart, but not conservative, decisions."

Unlike Dalton and Kap this past offseason, Newton didn't work with a quarterback guru. Instead, he played Knockerball, a game in which two people encased in huge plastic balls run into each other; practiced with an Australian Rules football team; made a cameo appearance in a flag football game in Atlanta; and finished his sociology degree at Auburn. But make no mistake: Newton grinds. Ask Dorsey for a play that Newton has made this year that he wouldn't have made last year and he instead describes an entire process, forged over years, the results of which are just now arriving. "He's underappreciated for the preparation he puts in," Dorsey says. On top of the notebooks, Newton polishes his already strong mechanics by focusing on a new point of emphasis each day in practice with Dorsey. Twice this year in the red zone, he has audibled out of bad plays and into touchdowns: Against the Saints he ran for the score, and against the Bucs he threw it -- the definition of a triple threat. Newton has become expert at combining "God-given ability," as Olsen says, with "taking what the defense gives him without losing his aggressive mindset," as Dorsey says.

Of course, none of these evolutions alone will change football. But if there's one lesson from Dalton, Kaepernick and Newton, it's that being a great quarterback is about committing yourself to the tedious with the hope that there will be something beautiful on the other end. A hope that nights like Newton has against the Eagles will become routine. As usual, Newton is the best player on the field. After the game, he exits the stadium in slacks, a vest, a jacket and tie and with headphones on his ears. A small circle of people sheepishly stare at him. "How y'all doing?" he says and poses for a few pictures. Just then, a golf cart comes screaming in reverse from 50 yards away and stops at Newton's feet, a perk of superstardom. He hops on to drive off to his car while the lingering fans begin to chant "Cam! Cam!" Newton waves to the crowd, and just as he does, fireworks go off in the background. It seems impossibly glamorous -- the opposite of everything that has led him there.