Emmanuel Mudiay is not scared

War-torn Congo, chaos at Dallas' Prime Prep, an injury-plagued season in China -- nothing has stopped this 19-year-old yet. Can the NBA?

n the back of a dimly lit ballroom at a midtown Manhattan hotel stands the 19-year-old many consider the most exciting talent among the incoming class of NBA rookies. He is 6-foot-5. He wears his hair in a small, fashionably tousled puff. He smiles broadly.

Nobody notices.

The room is full of sportswriters eager to talk. But most ignore Emmanuel Mudiay.

He settles his long-fingered hands carefully inside the pockets of his slim blue suit and waits. He is accustomed to this, "sort of sneaking up on people," he says. "I like it that way."

The ones being pushed toward the cameras at the NBA draft lottery on this May night are the collegiate standouts. They've been on magazine covers. They've battled through March Madness. They've been seen by tens of millions. There is Duke's Jahlil Okafor, the national champ, natty in a gleaming brown suit with a red handkerchief peeking from a chest pocket. There is Wisconsin's Frank Kaminsky, ruffled and reedy. "Frank the Tank!" bellows the master of ceremonies. "Frank the Tank!"

There, too, is the player almost everyone assumes will be taken first -- Kentucky's Karl-Anthony Towns. When he walks past, square-shouldered and focused, someone blurts: "Oh, look, Towns! It's Towns!"

Mudiay? He's surrounded by silence, until finally, a reporter sidles up. Then another. It's hardly a scrum.

There's a centered, soft-spoken stillness about him. As he answers their questions, the two reporters are forced to lean in to hear. After a minute passes, they leave. Mudiay slips behind a gray curtain and heads back to his hotel room.

Nobody notices.

He is the first basketball player from an American high school to skip college and go straight to Asia and play for the Chinese Basketball Association. He signed for $1.2 million. (Brandon Jennings paved the way in 2008 when he went to Italy.) Few Americans know Mudiay. Fewer have heard of his Chinese team: the Guangdong Southern Tigers. Even fewer have seen him play.

His peers have followed the slickly paved, tightly controlled path to the NBA: prep stardom followed by college stardom. They are young and eager, possessed of a kind of gushing, intercollegiate awe.

Mudiay is different. He's seen too much, lived too much, his life filled with more turbulence and uncertainty by 19 than most NBA players will see in their lifetime. He's ready for the pressure to lift, for the deadline to arrive.

He's ready to be noticed.

Emmanuel Mudiay was one of the top high school players in the nation, but he decided to play professionally in China rather than attend a U.S. college. As he prepares to be selected as a top pick in the 2015 NBA draft, take a look back at his journey.

TWO NIGHTS AFTER the lottery, at a tony prep school in Manhattan, Mudiay is polishing his perimeter game. His form is elegant -- a metronomic rise from slender ankles past sturdy hips, guided by sinewy, outstretched arms. For stretches, however, he misses as many shots as he makes. He leaves the court, brow tight with frustration, vowing that he will "keep on grinding." Two weeks later, inside a Dallas gym at almost midnight, he continues pushing, driving himself to exhaustion. This time he hits 17 of 20 from deep, including eight 3-pointers in a row.

He's lived with a monkish devotion to basketball since he was a kid, says he thrives off the "mind-clearing release" it provides. He counts on one hand how many late-night parties he's attended. He's had one small glass of alcohol, in China, when he worried that not finishing the wine poured for him at a team banquet would be viewed as a cultural affront. He spends free time with family.

His skills are rare for someone nearly six and a half feet tall. He dribbles low and nimbly. His feet pad across the court almost soundlessly. His hands are large; he palms the ball with ease. His bounce passes skim across the court with a casual flick.

Three weeks after the lottery, he invites reporters to watch him at a sprawling gym in the San Fernando Valley, north of downtown Los Angeles. One is Mark Heisler, who has covered basketball for the Los Angeles Times, The Philadelphia Inquirer and others since the late 1960s. Mudiay sprints and cuts and launches toward the rim, unfurling a series of tomahawk jams. "Explosive. Wow!" Heisler says, wide-eyed. He compares Mudiay to Russell Westbrook, Derrick Rose, a young Kobe Bryant -- even to Elgin Baylor. "I knew he was an athlete, but wow, I wasn't expecting this. It's possible that the moment he turns pro, he is the most athletic point guard there has ever been." Heisler pauses. He adds an appropriate dose of caution, the same dose NBA executives have added when considering Mudiay. "Right now, remember, he's working out against air."

Mudiay has a centered, soft-spoken stillness, and he prefers being out of the limelight. Fab Fernandez

INSIDE THE BEIGE living room of the Mudiay family residence in a working-class, mostly black subdivision in Dallas, Emmanuel sits alongside his mother, Therese. The home is tidy and no-nonsense: black couch, midsize flat-screen TV, Oriental rug lying atop wall-to-wall carpet. The only artifact suggesting this is where an accomplished young athlete spent his high school years is a square plaque given to Emmanuel for being named outstanding player at a basketball camp.

It's almost as if it's not Emmanuel's home. In many ways, it's not -- born, as he was, nearly 8,000 miles south and east, in Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly Zaire), a country that was mired in war during his early childhood. "Pressure?" he asks. "I was born into pressure that is bigger than basketball. When I'm playing, I will flash back about something that happened when I was younger, and I use basketball to take it out on that."

A beat passes. He rubs his hands together. "But the past I don't talk about much. My mom always says, 'Don't go around carrying scars.'"

Emmanuel was the baby of the family, just 1 year old when his father, Jean-Paul, collapsed at a barbecue and died. Emmanuel's brothers, Stephane and Jean-Michel, were 7 and 5; civil war was raging around them, President Mobutu Sese Seko clinging desperately and in the worst way to power. "Gunshots and protests and chaos," Therese says, her halting English laced with a French accent. "Chaos. Total chaos."

Before the war, the middle-class family had lived in a neighborhood shielded from the worst of the country's problems. But once the war started, no place was safe. Gunmen strafed the streets. Young boys strode past the family residence carrying automatic rifles. Homes were ransacked. Combatants killed their enemies by forcing them into tires up to their waists, dousing the tires with gasoline and setting them afire.

There were weeks when the violence was so severe that Therese would shutter her boys inside. Emmanuel remembers only a foreboding sense of terror. "I never actually saw somebody get shot," he says, fidgeting in his chair. "But I do remember hearing gunshots every night and seeing a dead body on the street."

Mudiay is the first American high school basketball player to skip college and go pro in Asia. Fab Fernandez

Stephane, the eldest, watched over Jean-Michel and Emmanuel, but Stephane himself was a target. He had a high forehead and a narrow face, causing him to resemble a Tutsi from neighboring Rwanda. "Back then," Therese says, "if they think you are Tutsi, they kill you. There was nothing good about that time."

Therese recalls praying one night on her knees, pleading for direction. "God, you are the father of the orphan and defender of the widow," she implored. When she rose, she was convinced that God wanted her family to flee. So in 2000, Therese cobbled together plane fare to Texas, where a sister lived. She would apply for asylum once she got there, then send for her boys, who would stay with their paternal grandparents in Kinshasa. They waited. Then they moved to Zambia and lived with a relative of their father. They waited some more. In the United States, their mother worried she would never see them again. At home, they feared the same.

“Pressure? I was born into pressure that is bigger than basketball.”

- Emmanuel Mudiay

On Sept. 11, 2001, the Mudiay boys huddled in front of a television and watched the Twin Towers collapse. They couldn't comprehend what had happened. They feared that their mother had been killed. Jean-Michel and Stephane say their little brother was with them. But Emmanuel, who was 5, cannot recall it, the memory perhaps buried by fear.

When the brothers finally joined Therese a year later in a one-bedroom apartment in Arlington, Texas, Emmanuel would not leave his mother's side and would watch as she trudged into the evening darkness to her job as a nursing assistant at an assisted living home. He would be awake by 7:30 in the morning to greet her when she returned.

For the older boys, basketball became a touchstone, their early flashes of talent helping them gain acceptance in a foreign land. It also introduced them to Lori Monette-Gardner, a civil engineer and coach who had gained a reputation for guiding young boys to success on the court, and a straight path off of it. She coached Stephane and Jean-Michel and came to know Therese and her struggles -- even paying rent and buying food were no sure thing on her salary. The coach and her husband took the boys in when they could, sometimes for weeks at a time, buying them clothes and food, offering the comforts of a five-bedroom house with a pool.

On a gravelly half court in the backyard, Emmanuel learned the game. He'd mimic the left-handed shot of his favorite player, Lakers guard Derek Fisher, with startling perfection. "At night," Monette-Gardner says, "you could hear him speaking through the walls, talking in his sleep, that thick French accent he had then, saying, 'Pass me the ball. Pass me the ball. Someone, someone, pass me the ball.' "

On Sundays, Emmanuel sat in church at Therese's side filling notebooks with drawings of the NBA logo and with promises to himself that he would play professionally. Once he made the NBA, he wrote, he would take care of his mother -- always.

-

Osports

BY THE TIME Mudiay turned 14, he was regarded as one of the best guards his age in the nation and had entered the fold of Ray Forsett, a former football player whose younger brother, Justin, stars for the Baltimore Ravens. Forsett coached at Grace Preparatory Academy in Arlington, a small school, predominantly white and Christian. Mudiay's freshman year, the team was loaded. Senior center Isaiah Austin was one year from starring at Baylor; three other upperclassmen would go on to play basketball at major colleges.

It wasn't easy playing for Forsett, who pushed and drilled and had each student write out his goals. When Mudiay wrote that he wanted to play in the NBA so he could help his mother, Forsett seized the opening. "You don't really want to take care of your mom," he remembers yelling. "You say you want to be successful so you can say 'Mom, you don't have to work,' but you don't really want that. You're not showing it. You're not showing me nothing!"

Mudiay hated the taunts but came to realize the barbs were good for him. "I don't think any coach will ever talk to me the way he did, even in the NBA," he says. "But he made me mentally stronger." Mudiay fought back by winning. When Austin was suspended after an altercation in the state championship semifinals, Mudiay scored 14 points in the title game and led his team to a win. "He just took over," Forsett says. "It was more than scoring. He wasn't going to let us lose. After that game, he really never looked back."

After a second state title in Mudiay's sophomore year, Forsett left for a new school -- Prime Prep Academy, a charter startup run by Pro Football Hall of Famer Deion Sanders. Mudiay and four other players followed, walking into a fire they didn't know was burning. Texas high school officials were outraged, as their rules barred students from transferring for athletic reasons -- and Prime Prep was a school touted for its potential to churn out athletic stars. Despite Sanders' assurances that he and the school had followed the rules, several of Prime Prep's varsity basketball players, including Mudiay, were banned from competing in Texas league play.

Nothing at Prime Prep was stable. The school's financial officer accused Sanders of assault. Sanders was fired from his position as football coach, then promptly rehired. There were allegations of financial mismanagement and administrative in-fighting. A state agency found that the school failed to meet academic standards. "The place was a mess," says one former board member.

Emmanuel didn't have much homework, but Therese wasn't concerned. Her son, she says, needed Forsett, who had become a role model for a young man without a father. Plus, to compensate for not playing in local leagues, Prime Prep sent its athletes around the country to play against some of the nation's best teams. While the school was swimming in controversy, Mudiay was developing an even higher profile, fielding offers from top collegiate programs and being touted as a possible No. 1 draft pick come 2015.

After two years playing for the troubled charter, Mudiay graduated. Seven months later, Prime Prep closed for good.

SHORTLY AFTER TAKING over at long-moribund SMU in 2012, Larry Brown sat in the narrow bleachers of a cramped Dallas gym. The Hall of Fame coach had driven to see a pair of lanky frontcourt talents, but from the start he was mesmerized by the point guard so in control of his scrimmaging team. "I started giggling," Brown says, of watching Mudiay play. He became convinced that the guard could already start for half the teams in the NBA. He told reporters that Mudiay was the best young point guard he had ever seen.

To help attract Emmanuel to SMU, Brown focused on Jean-Michel, who, hobbled by knee injuries, was trudging through an undistinguished season as a guard for West Texas Junior College. His biggest strength was his levelheaded maturity. Knowing that Emmanuel wanted to play on a team with his brother, Brown offered Jean-Michel a scholarship.

"I figured if he didn't get Emmanuel, then Jean-Michel would be a sh---y recruiter," Brown says, wryly.

It worked -- kind of. Jean-Michel barely played but became a quiet leader for Brown. And Emmanuel committed to SMU over powerhouses such as Kentucky and Kansas, but never set foot on campus as a student. Although the NCAA will not confirm any investigation, it reportedly was looking into Prime Prep's academic rigor and whether Mudiay and other Prime Prep graduates were eligible to play in college. "The whole situation felt like it was all about the adults," Mudiay says. "I did the work I was told to do. I had a 3.1 grade-point average and was ready to go to college for a year, but I was hearing that I wasn't going to be eligible for my first 17 games. I wasn't sure what was going to happen, so what I ended up doing made the most sense."

“All of this, it's draining. I just want it to be over, to be honest. Where am I going to end up?”

- Emmanuel Mudiay

At the 2014 Nike Hoops Summit in Portland, in a game featuring Okafor and Towns, Mudiay was the high scorer. A coach from China took notice. Du Feng, whose Guangdong Southern Tigers were part of the professional Chinese Basketball Association, had come to Oregon to watch. And what he saw was enough to bring him to Texas.

"We basically went over there to see what Mudiay was made of, to sit down with him and see what he was like," says Matt Beyer, an American sports agent working the Chinese basketball market who accompanied Du on the trip. The Southern Tigers were the Asian equivalent of the San Antonio Spurs, having won eight championships in the league's first 19 years. But the CBA has had its fill of former American stars who performed and behaved miserably, unable to assimilate into Chinese culture and to playing before whistle-swallowing referees in icy arenas where there were more empty seats than fans. Would Mudiay have the mettle?

"All you have to do is spend a little time with Emmanuel and his family to realize what he's made of," Beyer says. "He has a different kind of drive and maturity. He was one who wouldn't just survive China. Even at his age, he could thrive."

The Southern Tigers offered Mudiay $1.2 million.

When Brown, who had become close with Emmanuel, heard about the offer, he asked the Mudiays to meet. At the appointed hour, Therese, Jean-Michel and Stephane showed up at his office. But not Emmanuel. He says he was too stressed.

"Look, if you come here, it's only a seven-month deal," Brown told the family, drawing a chart to show the long-term financial benefits of playing in college and being taken first in the NBA draft. "I know we will be able to prepare you for the NBA, which is something I don't think you can put a value on. And I think you can create a brand, like Andrew Wiggins and Jabari Parker. You have been struggling for so long that if you can just hang on for seven months ... " Even in the recounting, Brown's voice trails off. He thought Mudiay might lead SMU to a national title. But the family would not budge.

"They said, 'We can talk about it, but we are making a million dollars plus a shoe contract [with Under Armour, which ended up signing Mudiay to an endorsement package]. When you hear the mom and you hear the kids saying, 'We don't want our mom to struggle anymore,' well, you go from having the best player in the country to ... " Brown grimaces. "All I can do now is hope that when his name is called [in the draft], that it is early on. I still believe it was the wrong decision."

Mudiay is the baby of the family, here with Jean-Michel (left) and Stephane (right). Fab Fernandez

ON NOV. 1, 2014, Mudiay suited up for his first professional basketball game. Daniel Ehambe, a family friend who accompanied Mudiay oversees, watched the 6-5 guard get knocked flat by what Ehambe calls a "forearm shiver." The referee, Ehambe says, glared at Mudiay with a look that said, "You think that's a foul?" Mudiay's early performances were not spectacular.

"He had never come up against pros, and that meant he was getting outfoxed by players who didn't necessarily have his physical skills," says Andrew Crawford, a journalist whose website, Shark Fin Hoops, chronicles the CBA. "There were some great moments, but he wasn't exactly taking over."

In the 10th game of the season, this time against the Xinjiang Guanghui Flying Tigers, Mudiay drove the lane and sprained his ankle so severely that some speculated he would be cut by the team. Guangdong kept him, but the next several months were filled with frustration. Mudiay knew his peers back home were becoming stars while he was riding the bench, his draft stock dropping. He homed in on his Bible. He downloaded documentaries about Muhammad Ali, countless clips of Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson. He hit the gym constantly, even in a boot. Inside his apartment, he practiced his bounce passes so often that the neighbors would call security.

"Relentless," recalls Jeff Adrien, an NBA vet who was one of his teammates. "He opened a lot of eyes."

In March, the Southern Tigers, down two games to none, faced the Beijing Shougang Ducks in a semifinal playoff. Du reshuffled the lineup to emphasize speed, taking Mudiay off the bench. He hadn't played a game in four months but managed to outperform Stephon Marbury, the former NBA All-Star who has become one of China's dominant players. Mudiay scored a game-high 24 points, had four assists and snagged eight rebounds, leading his team to a 110-99 victory. "China? Nobody really saw it, but Mudiay showed he knows how to really play the game," says a high-ranking NBA executive. "For him to stick it out over there and not leave when he got hurt, and then to show that he really knows how to play, that speaks volumes. We've got a future star in him, I have no doubt."

EMMANUEL MUDIAY DRIVES a sleek new Porsche Panamera, his only material nod to the riches soon to come, and a vehicle he's so uncomfortable in that he says he might trade it in for a Dodge. He maneuvers the car cautiously, wending through traffic on a wide boulevard in Los Angeles, easing into openings, all the while fielding questions.

Does he have what it takes to star in the NBA?

“I figured if he didn't get Emmanuel, then Jean-Michel would be a sh---y recruiter.”

- Larry Brown

He admits to keeping his feelings, especially about such things, bottled up. He says he'd rather observe than talk. He can be seen as aloof, or a bit cocky, or a bit shy. Perhaps he is a shade of all three; or perhaps he's just different enough, the product of such an unusual journey, that outsiders simply can't figure out what to make of him. He says he met Michael Jordan once and was respectful but unfazed. He imagines picking Kobe Bryant's brain -- and playing him one-on-one. "Yeah, he's gonna get me; he's Kobe. But I am going to get him too."

What does he think of Russell Westbrook, who represented Oklahoma City at the lottery?

"So many of the players in my draft class were like 'Yo, he nice ... that's Russell, y'all. That's Russell!' Am I supposed to be scared?"

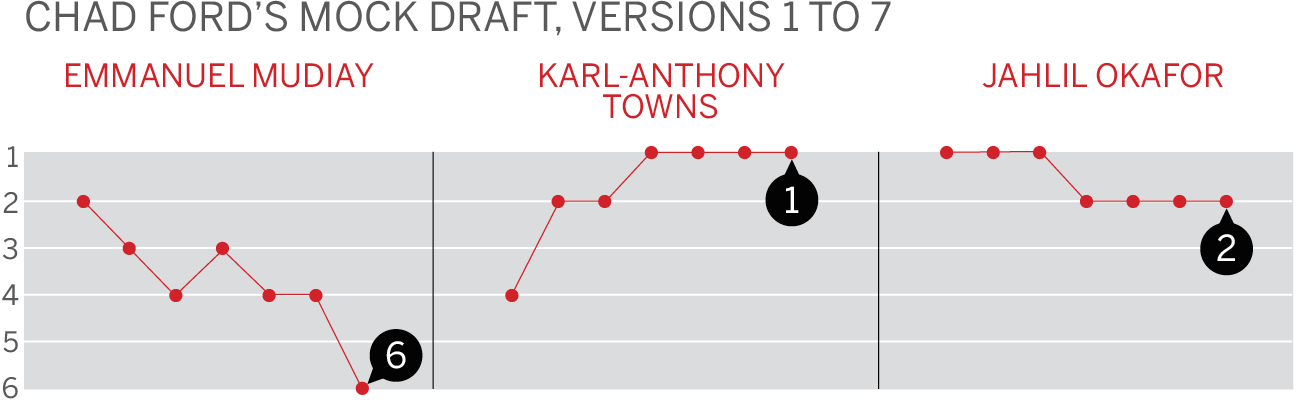

When not in Dallas, Mudiay, his mother and two brothers have centered their lives in the San Fernando Valley, an offseason haven for pro players because of its proximity to trainers and gyms. Emmanuel, Therese and Jean-Michel share the same small apartment. Stephane has a place of his own a few miles away. With the NBA draft near, speculation in the neighborhood is constant. Will the Lakers choose Mudiay over Okafor with the second pick? Could Mudiay fit into Phil Jackson's triangle offense? Is Mudiay such an unknown that he will fall to the Kings at No. 6?

The black Porsche noses forward. It feels as if his is the only car going the speed limit.

How does he deal with the pressure?

The past weeks have been a steady blur of cross-country flights, business meetings, commercial shoots, backbreaking workouts and private meetings with the teams most interested in his services. "All of this, it's draining," he says. He stops at a red light. "I just want it to be over, to be honest. Where am I going to end up?"

He stays focused by thinking of his mother, recalling her late-night shifts, her pain, his family's extraordinary journey. A few weeks ago, he says, he huddled with his family, as they've done since he was a kid, to pray and talk about life. When it was his turn to speak, he thought of his father, a man he cannot remember, a man known to him only through photographs and stories. What if Jean-Paul Mudiay were alive to see his youngest son poised for the NBA?

For the first time since childhood, he burst into tears.