9 Exits On America's Football Highway

A 540-mile stretch of I-20 in Texas reveals the state of football in the football state.

TEXAS is a place best seen burning gasoline.

Only up close, on highway after highway, can the state be glimpsed in all its joy, resentment and weirdness. Driving across it engages the imagination, which is where the story of the place takes shape. There's a song, "Levelland," by James McMurtry -- his father wrote Lonesome Dove -- that kept playing over and over on the journey across the state. It's about the road, and why people take it, and why they decide to leave it and build a life.

Flatter than a tabletop

Makes you wonder why they stopped here

Wagon must have lost a wheel, or they lacked ambition one.

On the great migration west

Separated from the rest

Though they might have tried their best

They never caught the sun

So they sunk some roots down in this dirt

To keep from blowin' off the earth

Each Texas story is incomplete without the pavement that connects it to all the stories that come before and after. The live oaks of East Texas bleed into the suburbs and skyscrapers of the Metroplex, which bleed into the cotton fields and barren plains out west, mesquite trees clustered by the road. Football is a cousin of these things, not a pastime to be thoughtfully debated but a geological formation, like a plateau or a reservoir of oil, one of those roots sunk down in the earth. And even as the state of football is seen as murky in many places across the country, in the football state, the game endures. That's an important word to Texans. We all learned about manifest destiny in school, most of us while living in a city or close to one, reading about how we made a great, unsettled continent our own, closing the frontier with the 1890 census. Only that's a myth. In some places, especially in Texas, the frontier is reopening -- the population of a county declining below the threshold of six or fewer people per square mile -- the towns settled in that mad rush west drying up and blowing away. Even Sweetwater, Texas, famed for the lakes it built to entice railroad tracks, is running low on water. Its football team was undefeated as of early November, running an unstoppable spread, and people packed the stadium when not praying for the fracking operation in the Permian Basin to bring more jobs. Existence is hard, and people live and die -- not in concert with the land but in combat against it.

The myth of manifest destiny lies at the heart of so many national conflicts; there are, in fact, two countries, the modern one firmly settled and the fragile one still fighting to keep those long-ago planted roots alive. Football is an expression of, and an escape from, and a symbol of hope for, that old nation. These are the things you feel only on the blacktop of Texas, where the stories begin to echo one another, and when the state's obsession with football starts to make sense.

Waskom

518 Miles East Of Odessa

The fortunes of the Waskom High Wildcats, occupants of a new football stadium the school district built among the refineries and post oak trees of East Texas, rest primarily on the shoulders of two cousins. Kevin and Junebug Johnson are waiting for their ACT prep class to end. Raised together by their grandmother, both ran for more than 1,500 yards last season, and Kevin will likely do so again this year. In two days, they have a game against West Rusk, and the next day, they've got the ACT -- the dividing line between the life they want and the one they have. Both took the test before and made 14. They need 18 to qualify for a four-year college. Coach Whitney Keeling waits for them outside the main office. He senses the importance of the next three days. "This is their only way out of Waskom," he says.

In class, the instructor works with Kevin and Junebug (nicknamed by his grandmother for being a small baby, and also a very black one), teaching test-taking skills. The cousins are popular with their peers and trusted by their coaches. Despite their difficulties with standardized tests, they grasp and process endless real-time information critical to the team's spread offense. A year ago, the team was 14-0 before losing in the 3A semifinals. The Wildcats have lost once this season and are returning to the playoffs. Never again will life give them as much autonomy and responsibility. Friday night flows through them.

"They don't ever make a mistake on the football field," Keeling says.

Around 3:15, the bell rings -- actually, an electronic tone sounds. Kevin glides over the shiny floor, taller by a head than his cousin. He wears a black Polo shirt and a red backpack, which he shoulders using both straps, the same as all his classmates. It's his 18th birthday. Right next to him is Junebug -- Bug to his friends -- only 5-foot-6, wearing trendy glasses and a senior class hoodie. A girl in their wake watches them walk, cutting her eyes and pretending not to care. Bug stops near the office when another girl with her blond hair in a bun wants to talk. He slouches and rubs his head, looking bored, now his turn to pretend. At the end of the long corridor, they bust out the door onto a covered sidewalk that leads to the locker room.

Both sit down in Keeling's office for a meeting, talking about goals.

"Having a great career," Junebug says.

"Graduating college," Kevin says softly. "Football may not always be there."

Keeling considers the two young men sitting in front of his desk. He loves them. "Your ass better do good on that ACT," he tells them all the time, "or you're going to be working at Dairy Queen the rest of your life."

text

The oil well that brought wealth to West Rusk in turn brought horror. Jared Moossy

New London

483 Miles From Odessa

An hour down I-20, Waskom's next opponent, West Rusk, is still trying to recapture what it lost. Two signs hang over each entrance to the school's field: home of the original friday night lights. Once, West Rusk High was London High School, and it was perhaps the richest rural school district in the country, proud home of a dominant football team, one whose coach outmaneuvered the superintendent in 1934 and spent some of that money on lights -- the first in Texas.

“Never again will life give them as much autonomy and responsibility.”

-

Four years before, in 1930, New London had been a poor farming village. Then wildcatters struck oil outside of town, a well named Daisy Bradford No. 3, and everything changed. The largest oil field in the world lay beneath a 200-square-mile patch of East Texas, which gave birth to many of the Texas oil fortunes, including that of H.L. Hunt, whose son Lamar would start the AFL, invent the Super Bowl and own the Kansas City Chiefs.

In New London, the population boomed. People slept in barber chairs and in tent cities and in cars. Every major oil company moved in, bringing workers and tax dollars, and the people of New London wanted what every boomtown resident wants: the wealth of their new life with the safety of the familiar one they left behind. They built a sprawling two-story beauty of a school and brought in roughnecks whose sons were great athletes, and the team wore its name under its new lights, the outward expression of the people's insecurities and their hopes.

Three years later, under the same spell of money, the school tried to cut costs on its heating bill. The board voted to tap into Hunt Oil's natural gas waste line. On or before March 18, 1937, the line began to leak, filling the school's basement with flammable gas. At 3:17 p.m., a spark in the shop class lit it on fire. Flames roared down the halls, and lockers exploded through the walls like cannonballs. The second floor pancaked on top of the first, crushing people beneath it. The walls turned to dust. Seventy yards away, a small child landed in the road, dropped from the sky, a truck driver slamming on his brakes. The first responders found shoes with no feet, feet with no legs. Parents working in the oil fields raced to the school, digging through rubble, putting torn pieces of notebook paper over lifeless faces. A reported 298 people died, most of them students.

A town lost a generation in a moment.

Few ever spoke of the explosion again. "As a schoolkid," says John Davidson, whose older sister Ardyth died in the blast, "I'd walk in front of this monument out here and have no earthly idea what it was about."

Growing up, snooping around in the attic, he found a small box nailed shut. He pried open the lid and found the clothes his sister died in, and the personal effects found on her body. Close to her for the first time, he turned over the tan and brown tartan coat with the broken wooden buttons. A diary lay on top, and he picked it up but didn't open it. Later, he'd wonder whether maybe he should have read a few pages. The box burned up in a house fire. "I just turned 74," he says. "Every day that goes by is a day closer to the day I will get to meet her."

Davidson graduated in the late '50s, a role player in a small-town football dynasty. The team won district seven times between 1954 and 1965, when the school closed. The oil fields had begun to run dry, and most of the companies left for another boom. New London and Joinerville, the towns on either side of the first well, ran low on money and students. They consolidated, becoming West Rusk. On the new football field voted for a few years ago, there is a subtle tribute to the tragedy of 1937 that fewer and fewer people remember.

The hash marks on both 37-yard lines are painted gold.

text

Allen built a $60 million stadium it can't use, so the two-time defending state champion Eagles play every game on the road. Jared Moossy

Allen

378 Miles To Odessa

A suburb is a modern-day boomtown, except instead of popping up overnight, it grows slowly until it's a sprawling city of its own, with every characteristic of a city except the most important one: a sense of place. They came to New London to find oil, and they come to places like Allen, north of Dallas, to find affordable land within an ever-expanding definition of a reasonable drive to work.

To get to the stadium that has become a metaphor for Texas football excess and myopia, turn right at the dentist office designed to look like a castle. Opened two years ago, Eagle Stadium rises above the surrounding low-slung neighborhoods. Locals voted for a bond to build, among other things, a $60 million stadium. The thing has a multitiered press box and a video board. Bronze eagles stand watch on the main facade. In a twist of the karmic knife, shoddy construction led to cracks in the stadium's concrete, forcing it to be closed for repairs. The two-time-defending state champs, winners of 35 straight, are playing every game this year on the road.

They built a $60 million stadium they can't use.

(Come now, it's not very Christian to laugh.)

The empty stadium is a monument to Allen's most naked ambitions, and in the media coverage of its failure, the stadium is portrayed as the most visible example of Texas' cancer: football trumping education. It opened as the state cut billions of dollars of school funding, and article upon article questioned the values, morals and even sanity of the community building a stadium during such fiscally bleak days.

None of those stories mentions the arcane piece of state tax law that led to the stadium. (The law gets convoluted, and even experts don't agree on its interpretation.) In Texas, by and large, a school cannot have an operating budget greater than $1.17 per $100 of taxable value. However, it can, in many instances, carry as much debt as the community is willing to stomach. In other words, Allen can spend $60 million on a stadium but cannot spend a penny of that $60 million to make up the recent cuts enacted by the state legislature. As a result, in wealthy school districts around Texas, especially in suburbs fighting not to feel part of a nameless, faceless borg, an arms race is underway. Allen didn't just build a stadium. It also built a performing arts center, used mainly by high school students, so cutting edge that acoustics can be changed with a push of a button. Allen has what its PA announcer calls "the largest marching band in the world," without any idea whether that's true or not -- and frankly, who cares? The 702 members, whose halftime show is pure chaos, more a display of excess than music, choke the field on this night with 16 xylophones, 23 sousaphones, a set of steel drums, plus the spectacle of flag twirlers and a dance team. Someone sent a catalog, and the person with purchasing power simply said yes ... to everything.

Up close, it feels like a patriotic acid trip, like the band director is a genius subversive enacting a piece of massive, overtly political performance art. Who knows? The band did play Green Day's "Holiday" in the first quarter on a recent Friday night, either wickedly funny or blitheringly un-self-aware: I beg to dream and differ from the hollow lies.

text

Southlake Carroll's stadium is smaller than Allen's, but still imposing. Jared Moossy

Southlake

341 miles to Odessa

In the past 10 years, the Allen Eagles and the Carroll Dragons have combined to win seven state titles. At Dragon Stadium, smaller than Allen's but still shiny and imposing, one of the sponsors is a local car dealership that sells Rolls-Royces, Bentleys and Porsches.

The parents of the Carroll quarterback, Ed and Megann Agnew, sit in the stadium's top row. Four sons have come through the program. Their oldest served in Iraq, and he just left the military for a job in oil and gas; during his deployment, he put a Dragons sticker on one of Saddam's palaces. This suburb is more than a cluster of freeway exits to them. The Agnews moved to Southlake in 1992, before the population boomed.

"We really liked that small-town approach," Ed says. "This was all rural farms."

"Horses and cows," Megann says.

About 5,000 people lived in Southlake when the Agnews arrived. Now more than 25,000 do. The value of their home has doubled. The school has moved from 2A to 3A to 4A to 5A to 6A. Several years ago, the community found itself divided over a vote. Should the town keep one high school or split into two? Many factors went into the decision, but ultimately the conversation was about the purpose of a school: Is it designed to transfer information from a teacher to a group of students, or is it the glue for a community? In a close vote, the town voted to keep it whole, for many reasons, including the football legacy. The history is taught and protected by a group of older men who call themselves the Dragon Council.

"We call them caretakers of the Dragon tradition," Megann says.

Almost everything about the school's fixation on tradition comes from a desire to have all of the good that comes with growth without any of the bad. The town even built a faux town square, centered on a green space, dotted with all of your chains: Anthropologie and Ann Taylor, Lucky Brand Jeans and Lilly Pulitzer. A sleep center for fat, snoring husbands and a fertility center for their wives. A plastic surgeon to hold off time, an orthodontist to fix imperfect smiles. Sports bars and dog bakeries. It isn't a town square as much as a eulogy for the town squares many of them abandoned in their journey here. The gathering place serves the same purpose as Allen's enormous, broken football stadium. They are cries in the wilderness.

We were here.

It's the suite life at Jerry World for oil tycoon T. Boone Pickens and his new bride, Toni, whom he impresses with every bottle of water he gets open for her. Jared Moossy

Arlington

335 Miles To Odessa

Jerry World is an object of easy scorn, the very worst example of a Texas cliché so pervasive it is reality too: the new-money, overfed, over-the-top, Botoxed, biceps flex of a small, small man. Then you walk inside the private owner's club and feel your scorn breaking down, slowly at first, by the chicken-fried steak with the best cream gravy in the state (hand to God), and the mac 'n' cheese so bafflingly good that at least one Dallas socialite has begged, to no avail, for the recipe. Turns out, Jerry World is badass. In the club, there's a bar, and clean, classic lines and lighting, and two more bars, and a country group playing guitars across the glowing room, and a guy in custom-looking boots -- Are those Becks from Amarillo? -- and men in bespoke shirts, royal blue with cocaine- white collars. In some rooms, an Hermès tie is just as Texan as a big, goofy hat. Hey, there's Emmitt Smith! There's Roger Staubach!

T. Boone Pickens' suite is 7R.

An assistant has laid out place cards inscribed with guests' names and BP Capital -- the energy fund that keeps the 86-year-old oil tycoon flush with cash and gasoline for his private jet -- and someone from the stadium put a mini Butterfinger bar at Boone's seat, because he likes them.

No one else gets candy.

He and his new wife, Toni, come in and sit down. They've been married for nine months. A widow, she was married to the guy credited with inventing the salad bar, which sounds impossible but seems to be true. Before him, apparently, there was no such thing as a salad bar, and then, poof, there was. He was just as rich as Boone, who recently saw his net worth slip just below a billion when he "lost his ass" on a wind farm deal. She's 65, smart and beautiful, and right now, she cannot open her bottle of water. Nobody near her can open it, and when Boone tries, he can't either.

His mind whirs.

When Toni isn't looking, he smoothly switches her bottle with his, cracks open the top and hands it back. She's aglow with the strength of her man, pulling out her phone and showing pictures of him doing pushups at Oklahoma State homecoming two days before. "That's my husband," she says. "That's why he can open the water. At 86 years old."

Pickens slips away to get a new drink, and he's confronted at the bar.

"What are you talking about?" he says coyly. Pressed, he grins.

"She didn't see," he says, turning for his seat, and in that moment, in an oil-financed private suite at a Dallas vs. Washington Monday Night Football game -- Cowboys vs. Indians! -- fresh off another successful bluff, T. Boone Pickens is the most Texan man in the epicenter of the most Texan place.

Soldiers unfurl stars and stripes that cover the whole field.

"Supposedly the biggest flag ever," Toni says.

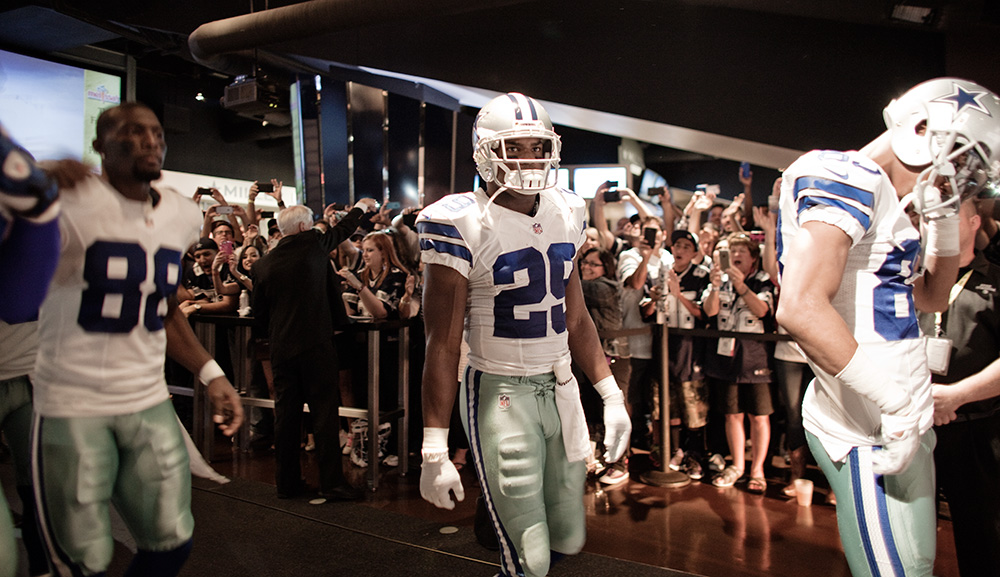

DeMarco Murray (29) rushed for 141 yards against Washington, but Colt McCoy, a Texan playing QB for the enemy, walked away with the win. Jared Moossy

THE COWBOYS LOSE their Monday night game against the Redskins, in overtime -- halting the momentum of their own nascent boom -- and the architect of their disappointment is a 28-year-old Texan named Colt McCoy. Actually, he's from New Mexico, where his dad was working at the time, but Brad McCoy left the hospital, drove across the state line to fill a box with dirt. He placed the box beneath the bed so his son could always say he was born on Texas soil. McCoy runs off the field after the game, escorted by team officials, headed into the guts of the stadium, where black SUVs and a white stretch limo idle.

McCoy steps into the interview room.

"Last night I felt like I was going to the Cotton Bowl to play the Sooners," he says. "That's the feeling I had in my gut."

He grew up south of Abilene, in Buffalo Gap, where wild hogs rut on front doors. On the outskirts of town, at a ranch on Farm-to-Market 89, a sign says pray for rain. Colt grew up in the Church of Christ. His dad coached football, and he planted more than knowledge and experience in his son. He planted a sense of longing in the young boy that grew as he did. Colt wanted to play quarterback, and wanted to play it in Texas, at the University of Texas, and he did, guiding the Longhorns to win after win, marrying the prettiest girl in a school full of pretty girls (a columnist once referred to her as "hotter than shrimp vindaloo"). His senior year in college, McCoy led Texas to an undefeated regular season, all part of the plan, but then got hurt on his first drive in the national championship game. Like Boobie Miles from Friday Night Lights (the book), or Smash from Friday Night Lights (the show), he left part of himself on that field. On Monday night, he picked a little of it up. And in the locker room, as he cuts off his own tape, he is happy.

A teammate, Adam Hayward, heads off with a new cowboy hat he bought.

"Colt!" he says, holding up the leather hat case.

"Put it on!" Colt says.

McCoy dresses and pulls his luggage down the concrete hall. Tonight, Colt found football nirvana, a moment of pure joy that briefly washes away the pain and disappointment of his injury and his limited pro career. He ducks into a lounge reserved for visiting family members, and just like after games in Austin, or even Buffalo Gap, he cranes his head to find his mom and dad.

text

Despite the hits he has penned for Kenny Chesney and the venues he packs in Texas, Charlie Robison pines for lost football days. Jared Moossy

Fort Worth

321 Miles To Odessa

Not everyone has a redemptive moment to balance the hurt. Most just live with it forever. In the back lounge of a well-worn tour bus, a country singer lights another cigarette. Charlie Robison doesn't think about his career, about the recent Kenny Chesney hit he wrote or the packed shows he plays all over the country. He remembers the football glory he held and lost.

Robison is whiskey drunk, and he rolls up his blue jeans, uncovering the hamburger meat scar stretching across his right knee. He was once a schoolboy star, and sure to be a college one, and now he's 50 years old. The loneliness of the bus and the endless shots fed him by fans leave him in communion with the ghosts of games past.

"I played tailback," he says, three words containing multitudes.

His senior year at Bandera High, a play had him blocking for the fullback. The guard pulled and knocked his man straight into Charlie's knee. Everything exploded: ACL, MCL, PCL, meniscus. "My patella f---ing fell down into my f---ing shin," he says. "That was 1983."

He lights another Marlboro Red, checking football highlights on the television. His knee aches when the bus rumbles along the highway, town after town, year after year. Vicodin helps him out of bed in the morning, 16 surgeries total on his knees. After so many concussions, he sometimes finds himself in the grocery store without a clue why he's there. His 11-year-old son, Gus, is a star athlete who refuses to play football; he says watching his dad get out of bed cured him of that temptation. Charlie needed football, to sort out who he was and to become who he wanted to be, living in rough-and-tumble Bandera, a place still fighting for itself. His son, living in a moneyed enclave near San Antonio, doesn't ask those questions. Football is something from his family's past he wants to avoid.

Baseball is Gus' sport, and Charlie coaches his team. Instead of pushing his son to remake his mistakes -- which his hard-driving father, also a coach, pushed him to make in the first place -- Charlie celebrates Gus' decision, even brags about it, understanding on some level that it makes all the pain that football caused him somehow mean something. A cycle has been broken. Recently divorced, he schedules his tours around his kids. His face glows when he shows off their pictures.

He starts to cry.

"Man, I'm sorry," he says. "You know, driving to school every day is the best time of my life."

Maybe it's the whiskey. Maybe it's that he's started down a hill too steep for stopping. Regret and unfulfilled promise bloom in the shadows. Before his injury, he'd been recruited by all the schools: Tech, A&M, Texas. Suddenly, there's a song he badly wants to hear: "No. 29," by Steve Earle. After some searching, it starts on a phone. He lights another Marlboro. Tapping his feet, he stares glassy-eyed at something only he sees, as Earle sings about a small-town plant closing, and an old football player leaving his glory days behind. Charlie takes a drag and sings along. The second verse kills him.

We were playin' Smithville ... big boys, farm boys

Second down and four to go

Bubba brought the play in ... good call, my ball

Now, they're gonna see a show

But Bubba let his man go ... I cut back, heard it crack

It still hurts me but I don't mind

Reminds me I was Number 29

Charlie closes his eyes for that verse, clenching them tight. The tears leak out anyway. The bus hums with the ambient noise of a generator, and he wipes his face. As much as he liked football, Charlie loves the thought that his son will never sit in a dark room, his body and mind damaged, crying over something he lost when he was young. Tonight, that feels like a victory.

Lance Morris rushed for nearly 12,000 yards on his six-man team. Now working the rigs, he won't take his next run at the game for granted. Jared Moossy

Ira

99 Miles To Odessa

Kids in crew cuts walk down the road in letter jackets.

Two years ago, Lance Morris was one of them, the king of them, 179 touchdowns and almost 12,000 yards as the greatest six-man football player ever. Now he works in the oil fields, 10 days on, four off, a pumper for Apache Corp. Today he is off and meeting a reporter at the school. The students are at lunch, and he walks the empty halls to his old locker, No. 7, painted orange. Morris opens it and looks inside for a moment, carefully closing the door.

Hands in his pockets, he heads into the locker room, standing in front of his old spot, the air sweet and rank. As a senior, he broke the national high school record for career rushing yards, but a running back from Florida, Derrick Henry, broke it too, the very same night, ending his career with 258 more yards than Morris. Now he watches Henry play on Saturdays for Alabama.

Tuscaloosa couldn't be further from this wooden cubby in the small Ira locker room.

"This was mine," he says, pointing to the stall on the end. "My brother took it over."

Logan Morris is a senior, averaging 240 yards a game, hoping to win a state title and then be a fireman. Lance helps his brother break down film, even comes to the pregame locker room to talk to the team. He does everything except what he misses most: feeling the bruise of contact, the freedom of an open field. He wants it back.

There's a minor league indoor team in Odessa, and it has open tryouts in February. Lance has been training again, pushing a sled, lifting weights, working on his speed and footwork. The boys in the oil fields are pulling for him. When Lance thinks about his career, he doesn't think about the glory -- he honestly doesn't remember his career yard total -- but about the growing regret, the lingering thought that he didn't give every part of himself, that he took that flicker of years for granted. He won't ever make that mistake again, if he can just get one more chance. If he ever gets to stand in the backfield again, he will give every piece of himself, flexed and ready, the crowd buzzing, waiting for the blur to begin.

He's 99 miles and four months from Odessa.

Odessa

The last stop on the road is the home of Boobie Miles, the Permian Panthers and the newest boom in Texas. As long as the price of oil stays above $60 a barrel, the twin cities of Midland and Odessa -- white and blue collar, respectively, or ... "raise a family in Midland, raise hell in Odessa" -- will continue to swell. It's about $80 and falling now, at a three-year low. In his office, suffering from his own anxiety about what might be over the horizon, new Permian coach Blake Feldt is in rebuilding mode.

This is his second season. He arrived to find a mess.

"All that was left of the program was the fluff," he says. "The concrete things have been lost. But boy, we're gonna do the pep rally the same and our uniforms are the same."

He sighs.

"Right now," he says, "we're just trying to make the playoffs. If we win Friday night, we'll be in."

The myth of the Mojo dynasty outlived the dynasty itself, which poses a delicate question about myth: Was the it ever real? Put another way: What would people think about Permian, and what would Permian think about itself, had there never been a book? Friday Night Lights, which people in town love to trash, is about them because they were good right then. If Buzz Bissinger had been born two decades later, he might have written his opus about Allen or Southlake. Any other number of Texas high schools could have been the setting for the story.

Whatever the past, Permian won the last of its state titles in 1991, and the Panthers no longer have the athletes to compete with the powerhouses in Dallas. With the oil and gas boom, Feldt wondered whether any of these workers coming in might bring stud athletes with them.

"He was really, really stuck. Stuck in the fact that he was the football star."

- La Donna Alexander, Boobie's ex-girlfriend

"It hasn't for us yet," he says. "That's shocking."

The school is growing. Permian is bigger than it's ever been, and a lot of the oil workers have brought young children with them. If the boom can continue, and about a thousand other ifs, then someday those kids might play for Feldt on Friday night. "The elementary schools in Odessa and Midland are busting at the seams," he says.

The town feels lawless, with fatal car wrecks and violent crime every night. Along I-20, man camps house people who cannot afford to pay the rent in Odessa or Midland. People worry about the bubble popping, because the excess is out of control: endless piles of cocaine and men flying private jets to see Justin Timberlake in San Antonio, and recently, an oil company paying the rapper Nelly a rumored $100,000 just to hang out at a Midland bar. Cab drivers are paying $900 a month to rent a dump. Even Coach Feldt can't find a house to buy. His family almost ended up in an apartment: a three-bedroom, about 1,500 square feet, renting for $2,300 a month. Last year Midland ended the 26-year run of Connecticut's Fairfield County as the nation's richest place per capita.

The famous 1988 Friday Night Lights team, and the 1989 team that actually won a state title, played in the bleakest economic period in the city's history, six years after an oil collapse gutted nearly every business in town. The team wasn't a representation of some oil-rich juggernaut but a survivor from brighter days. Something to hold on to, proof that they might endure.

Only a few of the guys are left. Coach Gary Gaines moved after the 1989 title to try working in college but returned to coach Permian again, chasing shadows, and he failed; Feldt replaced him in 2013. Tight end Brian Chavez went to Harvard and became a lawyer, but four years ago he pleaded guilty to a home invasion charge; a former teammate pleaded guilty along with him. Boobie Miles is an unseen name whispered in passing. He's been forgotten in town for many reasons, mostly because his knee injury is a reminder that life often has little in common with the myths we create to survive it.

"Where's Boobie?" the coach is asked.

"He lives, I think, in Crane," he says. "He drives a truck."

Feldt, a confident, good-looking man, seems sad.

"I've never met him," he says.

text

Boobie Miles' ex-girlfriend, La Donna Alexander, says Miles is haunted by the memory of his potential. Jared Moossy

Kermit

46 Miles West Of Odessa

Boobie does not drive a truck, or work in the oil fields, and he's not in Crane.

For the past two years, James Earl Miles Jr. has been Texas inmate 01833528, held in a facility near Beaumont, roughly 600 miles east-southeast of the boomtown where he briefly made a legend. Miles got into a fight with his brother, received probation, didn't pay restitution and is now doing 10 years. He is eligible for parole in 2017.

His ex-girlfriend, La Donna Alexander, wants to meet at a barbecue joint in Kermit. She described him as haunted by the memory of his potential and his injury, which remained a topic of daily conversation until he went to jail.

"He talks about it," Alexander says. "All. The. Time. Literally. When I first met him, we watched Friday Night Lights 50 times. I swear we did. He says if he hadn't messed up his knee, he could've been in the pros. He says that all the time. Much of the time, I just want him to be quiet. I get it. I. Get. It."

Part of her understands his pain because he has lived a hard life: abused by a family member, then abused in foster care, then injured during a preseason scrimmage his senior year at Permian. Before that play, he'd been recruited by every major college in the country. After, he started the spiral that ended in a Beaumont cell.

"He was really, really stuck," she says. "Stuck in the fact that he was the football star, and that's how he acted most of the time. He did not like going to Permian. It's like they used him and threw him away when he hurt himself. He's still in shock. To this day, he's like, 'I don't understand.'"

The only person connected to the old days who never forgot Boobie, she says, is Buzz Bissinger, who wrote the book that both made Miles famous and ruined his life. As 40 approached, Miles looked up and found two people who hadn't run from him.

"Me and Buzz," she says.

Alexander pulls up a Facebook page and shows Boobie's teenage son, James, already playing football, looking tough wearing No. 3. He's starting down the same road as his father, hoping to find something different at the end. He too believes in the life-changing potential of his talent.

Before getting arrested, Miles spent his time daydreaming. Working didn't work for him, and he would quit, or get fired, coming home unemployed, settling back in front of the television. Most days, he did the same thing. Alexander would watch, almost in pity, as he turned on his Madden game, a 40-year-old man disappearing into his imagination.

"He starts screaming at it like he's there," Alexander says.

He played whole seasons, naming the star of his team Boobie Miles. On the screen, his dreams had come true. The avatar even looked sort of like him.

"That's not you!" she would yell.

For hours, Miles would run free and uninjured, untackled by the best defenders in the world, until he pulled himself back into his real life, a dark, small room, clicking off the console as the screen went black.

Follow ESPN Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader

Join the conversation about "Big Man Still On Campus."